Next Saturday, Susan Orlean will discuss her new memoir Joyride at Portland Book Festival. In it, Orlean tells of the stories she reported at WW. “I wrote about a horrible murder/suicide. It is the only murder story I have ever written. I was so haunted by it that I knew I could never do another.”

This is that story. It first appeared in the June 22, 1982, edition of WW.

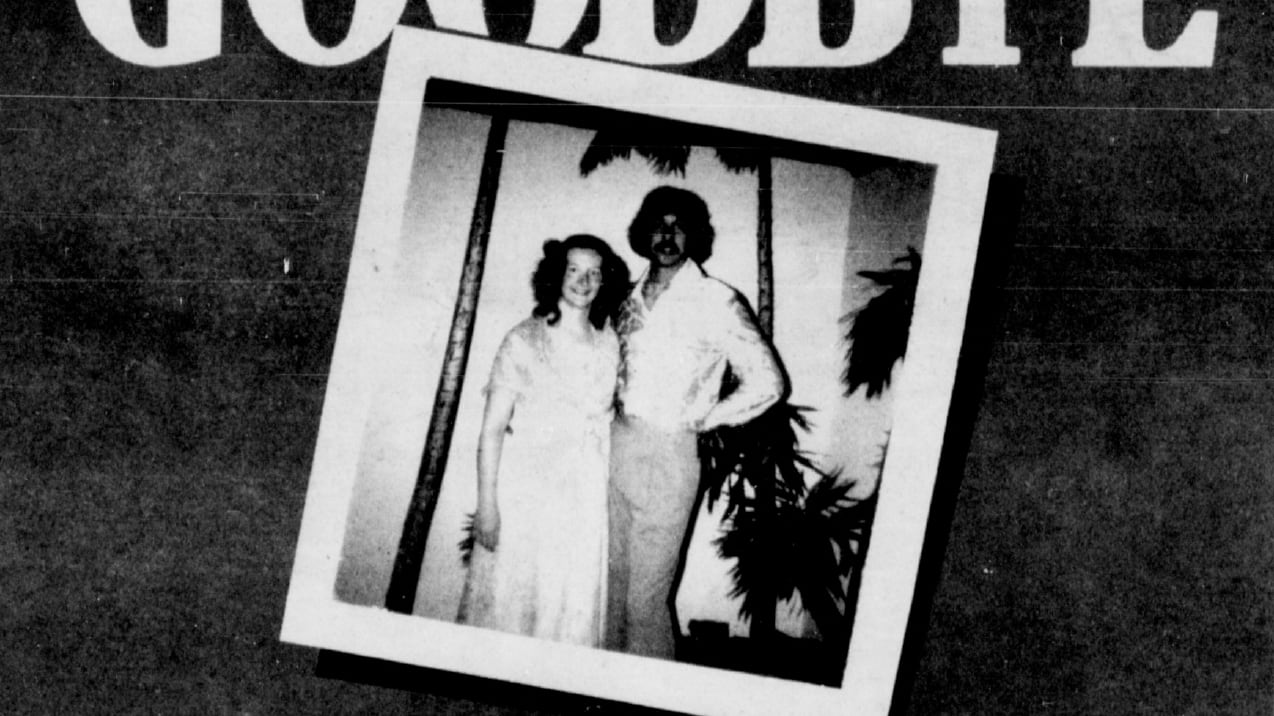

There’s a photograph of Steven Wallace Irwin taken on the day he died. There he stands, a young man, nearly six-and-a-half feet tall, narrow build, black hair. His expression is shy, almost dour, and his stance has the awkwardness that only a camera can induce in us. The friend who snapped the picture (he had repaired her sink only moments before) probably teased him a bit to relax and pose more easily with the burst of pink rhododendrons framing him. but Steve didn’t seem to take to it. This last document of Steve Irwin’s life shows him a little out of sorts with the world but otherwise blankly unremarkable. So unremarkable was he that a prison official, reading the next day of Irwin’s murder of his wife and his suicide, did not recall that she had interviewed him just a few days before, nor was the officer who signed his bail receipt able to conjure up the slightest memory of Steve. Nor can his family quite believe that a young man of humor and poise could regularly beat his wife, and finally kill her. Moreover, they can’t understand why he would want to kill himself.

Battle Ground. Wash., being a healthy distance from the freeway, is a small town that’s been spared those ugly clumps of development that sprout around highways. The town, a shade northwest of Vancouver, consists of a few blocks of gracefully aged storefronts and filling stations. The cafe where Steve Irwin’s mother last saw him alive is near the end of that stretch, and it hasn’t changed much since it opened aeons ago: red vinyl stools spin on chrome stems, the coffee is watery, and the prized booth is over in a corner that affords a perfect view up and down Battle Ground’s main drag.

Steve grew up on a long, straight road just west of Battle Ground, close to the high school, which he didn’t much care for, close to the lake, which he liked, and close to lots of other long, straight country roads that gave him ample opportunity to charge around in the cars he tinkered with, which he loved. He especially loved, recalls his brother Dean, taking a hemmie or a fueler or any car he could coax into action, and tearing down the open road at close to 100 mph. Then whipping into a U-turn and heading back just as fast. If he wasn’t fiddling with his cars, he liked to stretch out in the sun. Unlike his brother and a lot of Battle Ground residents, he didn’t like to fish or hunt. Guns made him edgy.

When he had had his fill of school, he dropped out and began to dream of the future. He spent time in Florida parking cars and wishing he owned a limousine; what with all the old folks and the heat and his fondness for driving, he figured he could make a great living carting people around. But he came back to Battle Ground, partly to visit his sweetheart. In 1975 they married, when neither of them had yet reached 20 years of age. A little over a year later, with a baby on the way, they divorced.

He still dreamed of returning to Florida and the limousine, but in the meantime he had to make ends meet. He got work with a moving company and, once he’d learned the trade, set out on his own, renting trucks and hauling people’s stuff for them. He liked not having a boss breathing down his neck, but found it tough when customers took advantage of him, bouncing checks and never paying. Once, after he’d moved a woman’s belongings across town and up several flights of stairs, she flatly declined to give him his money. That time, he took her television to try to settle up, but most of the time he’d let it slide. In general, you’d have to do an awful lot to provoke Steve Irwin, and even then, he was likely to sigh and say, “I guess there’s nothing a person can do about it.”

No one in either family particularly remembers when, or where, Steve met Betty June, but the two clicked pretty quickly and moved in together. She was a Portlander, raised in the lap of Northeast’s Concordia neighborhood. Like Steve, she had spent some years finding her niche — pretty rebellious years, but now she wanted nothing more than to tend a home and a family. Steve was terrifically in love with her, maybe even beyond love. He really wanted them to be bound together. Still, it grated on him that she had any past at all, and especially that she had had black friends. He even felt she had tried to trick him. He once look his mother for a drive to point out the taverns in Albina where he imagined she had spent time, but afterwards he just sighed and said, “I love her. Mama, I really do.” Throughout the marriage, he was consumed with the thought that June was seeing other men, especially when he spent long weeks away on moving jobs.

By some accounts, it was an odd match. He loved Miller High Life and drank it in quantity and enthusiastically; she didn’t drink. She liked to smoke marijuana now and again; Steve couldn’t abide drugs of any sort. It’s not that he refused to associate with the drug world (in fact, a good friend of his is now serving time for a murder committed during a cocaine deal), but he couldn’t stand getting high. It made him paranoid, and aggravated the sense of inferiority that lay just beneath his normally imperturbable calm. June was confident about her place in the world; Steve wore his soul inside out, shining when encouraged but shriveling if he felt belittled or betrayed.

The relationship was tumultuous, but nevertheless, Steve and June married in 1979, three years after they had met. Their son, Nathan, was born the next summer. Two months later, June filed for a legal separation and got a temporary restraining order from the court to keep Steve away from her and the baby, claiming that he had abused her. They patched things up and she decided not to proceed with a divorce. A year later, she once again requested a separation and a restraining order, and once again, less than a month later, they got back together. They’d make deals with each other — he’d stop drinking if she quit smoking pot. He couldn’t trade her anything but a promise that he’d stop beating her up, and June believed it. She convinced him to see a counselor with her a few times, but they didn’t keep it up for long. None of the deals and promises lasted, and the police computer can produce a long list of calls June made when things got out of control again.

That was the dark side, the side that most people never saw. The public side was a young couple getting a start in life, a darling child, Steve’s neat new business cards, June’s primped and patted garden. There was never quite enough money, but Steve’s mother had remarried and come into some beautiful land outside Battle Ground. A lot was already set aside for Steve, complete with some knee-high Douglas firs he had lined up, and the prospect of even more, provided he outlived his mother. With all this to look forward to, Steve Irwin seemed to have every reason to want to live forever.

For June, everything had become a confusing jumble. She couldn’t get over her attachment to Steve, even when she had just been beaten. Since her own parents had divorced when she was young, she never really knew her father and she was determined that her son wouldn’t suffer similarly. She was busy working as a part-time housekeeper as well as running her own home, and happy when things were going well. When they weren’t, she felt sure that she had been singled out by the world for punishment. Even at the end. she dreaded the notion that Steve’s family might hate her for wanting out.

On April 23, June filed again for a restraining order, a decree issued through Domestic Relations Court limiting Steve’s access to her, Nathan, and their home. Usually. Steve would be contrite and ashamed after he’d attacked her, and would snap back to his usual self, being extra affectionate to make up for what had happened. This time, though, he didn’t seem to snap back, and June was afraid. In her affidavit, she charged that Steve had “abused [her| both physically and mentally and has, as recently as April 19. 1982, threatened to kill [her].” She requested that he be kept from using their house in Northeast Portland, which angered Steve, since he had paid rent on it in advance. If he disobeyed the conditions of the order, he could be imprisoned. June noted that he drank excessively, and drove “like a maniac.” which cut Steve, whose every joy and dream included cars, to the quick.

They were in the house together once more. He cut off chunks of her hair and threatened her for hours. June thought he might have killed her had Nathan not screamed and wept. When it was over, she talked him into going to a crisis center, where he was interviewed and released — vindicating his family’s unshakable conviction that he was perfectly well. Defeated, June made the now-familiar trek with baby and suitcase in hand to her parents’ house. She was determined it would be the last time, and she was right.

Her mother bought two books on battered women, and together they started devouring them. For the first time, June felt less strange about what had been happening with Steve, and she finally admitted that divorce was the right thing to do. It seemed nearly settled. On Wednesday, May 12, June followed her usual path to the house where she went to work. It was a little before 9 am, but the gardener was already out tending the yard. She hadn’t seen Steve in days. He stepped out of some bushes and stopped her. “Are you coming to my birthday party?” he asked her. She said no. “You promised you would call,” he said. Suddenly she noticed he had permed his hair. So had she — to cover up the spots he had cropped off. It shouldn’t have mattered, but she read it as some terrible omen. He knocked her over and kicked her and went back to their house to wait for business calls. The police found him there a few hours later and tangled with him a bit before leading him to the patrol car. June’s mother covered Nathan’s face so that he wouldn’t watch Steve leaving.

He was booked into Multnomah County’s downtown jail at 6:40 pm on Wednesday, May 12; the charges were Assault IV, a misdemeanor with the maximum penalty of a year in jail and a $1,000 fine, and Violation of a Restraining Order, a matter that would be heard in Domestic Relations Court, with punishment at the discretion of the judge. He went into jail with one brown belt, 10 keys, one black wallet, and $8.65. In his mug shot, he looks stiff and ashamed, with his eyes focused shyly above the camera. He needed $550 to bail out — 10 per cent of the $500 assault bail and the $5,000 restraining order bail. He called his father in St. Johns. “Hi, Dad,” Steve said flatly. “Where are you, son?” “Oh, I’m in jail. Dad,” he said wearily. His father assured him they would get him out. It would just have to wait until morning so that his mother could get down from Battle Ground. Steve sat down to face a night in jail.

There were few things Steve feared in this world, but he had a dread, a horror, of going to the penitentiary. He had spent nearly a month in a corrections facility for reckless driving a few years earlier, an experience that riveted that dread. Even his brother, who figures he knew Steve like the back of his hand, couldn’t fathom Steve’s aversion. It was more than a fear of being locked up: it was the notion of prison as a disease-ridden hole, even just the horrible sound of it. Still, he didn’t spend his night in jail ranting and raving and cursing everyone in sight, as many newcomers do. He spent it quietly and without incident, hardened by his horror and his resolve that he would never go back again.

In the morning, he was led out to be interviewed, to determine whether he could be released on his own recognizance since he hadn’t yet bailed out. Because one of the charges was for assault, and the interviewer couldn’t contact June, she recommended against allowing Steve to leave. She called June’s mother, who repeated the request that Steve stay in jail, and a note was attached to his recog papers, saying, “Contact was made with victim’s mother . . . as victim was at courthouse filing complaint. She states victim feels threatened by [Steve] as he has stated he would kill her if she called the police.” Though not run-of-the-mill stuff, such things are not unusual at the courthouse, and the message was duly recorded and passed along routinely.

That same morning, June met with her new lawyer and helped him prepare a case to have Steve’s bail raised on the restraining-order violation. They contacted witnesses, who agreed to appear at the 1:30 hearing in Domestic Relations Court, where hearings often take the form of trials. June then went over to the courthouse and saw Steve’s parents in the hall. Because his mother and hers had argued the night before, she felt uneasy. They barely noticed her, but she was convinced that they glared angrily — it was still hard for her to believe she was right.

She didn’t know that Steve’s parents had just signed the bail receipt, releasing Steve from jail at 9:56 am. He was upstairs at the jail gathering his belongings to leave the courthouse for good, since his two hearings were both automatically cancelled once he made bail. His 2 pm assault hearing in District Court was set over, as usual, one week. Accordingly, his Domestic Relations hearing was cancelled, too. He was instructed to call that court the next day for a new hearing assignment.

At 1:30 pm, June and her lawyer waited tensely for Steve to appear in the Domestic Relations courtroom. They’d make their plea to have his bail increased; maybe Steve would even have an outburst in the courtroom, which would strengthen their case. When he didn’t appear, they assumed he had skipped out, and her lawyer urged the judge to issue a warrant for his arrest. Only later did they catch up with the paperwork and realize he had departed properly bailed and instructed. There was no way to get him back; nothing the lawyer could do but ask for an expedited hearing date on May 24, which he got, and urge June to leave town. A few hours earlier, unbeknownst to any of them, the Domestic Relations scheduling clerk had called upstairs to the courthouse jail to complain about Steve’s hearing setovers. It was the second time in recent weeks that an attorney had come to that court to motion for increased bail, only to discover the defendant had bailed out so soon that the Domestic Relations Court was never notified. (See sidebar.)

Steve and his mother headed over to his house so that he could pick up a few things. He disappeared inside and emerged a few minutes later with his shaving equipment, a quilt he got for Christmas, his cat, a quart of milk, and the hand truck he used when doing jobs. He had hurt his foot a few weeks earlier, and he limped along as if each move sapped him of energy. He went to stay at his father’s house in St. Johns. June went back to her parents’ house and her books on battered women.

The next day, Friday, May 14, was Steve’s birthday. He spent that day, and the next two, uneventfully. He was quiet — maybe a little quieter than usual. He missed Nathan. He tried to figure out what to do next. First, he had a moving job in Palm Springs. Then what? On Monday, he and his brother were tooling around Battle Ground, and stopped at the cafe at the end of town. He noticed his mother across the street at the grocery store; she came over and sat with the two of them. Steve was still gloomy. “Steve,” she chided him. “these are domestic problems. This isn’t for the court! Fight her! Fight it!” She had covered his bail for his birthday; now she offered to get him a lawyer. He listened, but his goodbye hug was a little vacant. Then he just said, “See you, Mom,” and the two brothers left.

On Tuesday, he fixed his friend’s sink, posed grudgingly for a photograph, and returned to his father’s house. At 5:31 that evening, a process server came by with new papers from June’s lawyer. Because Steve refused to touch them the server left them on the front lawn and waited in his car for Steve to take them. The wind, kicked up by trucks barreling by, tossed the papers across the yard. Steve waited until he was satisfied that the courier’s car had crept out of sight before he would pick them up.

June spent her days with the baby, with her lawyer, doing her work. She went nowhere alone. She and her parents talked to counselors and psychiatrists about wife beating. She told her lawyer about the last few times she and Steve had been together. On Tuesday, she went with her sister and mother to talk to a counselor at Kaiser-Permanente. She asked him if Steve might not just overcome his fear of guns and get one to kill her and himself. The counselor doubted that Steve was suicidal, but he did warn June, as she had been warned before, to watch out. She said she felt like a fool for having waited so long to leave him.

That evening, she made plans to have dinner with two girlfriends. Her stepfather would drive her there and her friends promised to bring her home. She dressed for dinner, then went back to reading her book Battered Wives until he was ready to drive her over. She bent it open to mark the page, cracked the spine a bit, placed it face-down on page 166, and left for dinner.

Steve couldn’t believe the affidavit he had received. It detailed a day he and June spent together in the house, when he had threatened and assaulted her for hours. She listed that he terrorized her with a knife and an axe, chopped off pieces of her hair, choked her and vowed to kill her. She stated that he had forced her to have sex with him. She wanted him to see Nathan only under supervision, and she didn’t want him to be allowed to take Nathan in a car with him. He started thinking about Nathan, and wondering if June were taking up again with her black friends. He couldn’t abide the thought of his son’s being raised around black people. His mother had called June the night before to see if she might drop the charges; June had been cool and evasive. Maybe he’d try again.

He called his mother at 7:56 pm and said he wanted to talk. She reminded him that it was too late for her to come to Portland, and told him to meet her at 9 the next morning. They’d talk then, have a little breakfast, some coffee, and then he’d meet with a lawyer. He then called a friend, and explained that he had a moving job in Montana and wanted to do some rabbit hunting on the way. He picked up a six-pack of beer, told his brother to expect him back at 10, and left to get the gun. Maybe he had actually convinced himself that he needed it in case June had some touchy guards around her; at any rate, he wasn’t particularly distracted or impatient when he got to his friend’s house. In fact, they had a couple of beers and chatted a bit before Steve left.

At a few minutes after 9:30, June and her friends went home. They circled the block several times before letting June out at her parents’ house. Neither Steve nor his car was to be seen. June got out of the car and crossed the street, walking behind a pickup truck, parked facing west, in front of a trailer. The first shot was from a short distance and knocked her onto the sidewalk. It is unlikely that June ever saw Steve’s face, even when he walked up close to her. The second shot was point-blank. One of June’s friends, running from the car, found Steve lying some 20 feet away from June with the gun close to this quivering leg; the friend moved it away in case he somehow revived. He died the next day. The bullets were fragmented, and thus can never be matched with those that killed June, but the consensus between police and the medical examiner is that Steve’s was a self-inflicted wound. His car was discovered a few blocks away in the direction he had apparently been heading after shooting June. He had waited for her outside the house for nearly an hour. For part of that time, he probably thought he would talk to her. The other part of that time, he must have realized she would never listen.

No one concerned rests easily, even though the fighting and reconciliations have ended. The child’s custody is still in bitter contention. Each family, too, reads the event like tea leaves and each sees a different pattern in the bottom of the glass. One sees that it was the horrible, but predictable end wreaked by a sad, sick man; the other, that it was the awful toll paid when a sensitive, vulnerable man is torn apart by pressure and doubt. At least a few of them are sure that one day Steve and June will appear in their dreams and try to tell them why it had to happen at all.

Steve Irwin: Out of Reach

Could the courts or the jails have done anything to save June Irwin? “Steve’s release was a missed opportunity.” says June’s lawyer, Bruce Byerly. “No one can say what might have happened, but it was a missed opportunity.” The confusion over Steven Irwin’s release from jail occurred because of a weak link in the system, which lines up arrested people with court dates. Usually, a suspect is jailed and bails out soon afterward, in which case he or she is assigned times either to appear or to contact the appropriate court. If the suspect is not released (on bail or recognizance), the court (or courts, if the charges are various) hears and arraigns the next day. Misdemeanor hearings can often be complicated, with witnesses and motions.

In Steve’s case, because he was booked one evening and didn’t bail out, the next morning he was assigned a hearing time that afternoon for his assault charge. The jail’s Recog Unit then called the Domestic Relations Court’s scheduling clerk, to say that someone was in custody on a charge to be heard in Domestic Relations Court as well. Shortly after that, the Domestic Relations scheduling clerk called the Recog Unit back with Steve’s hearing time. (Unlike other courts, Domestic Relations does not have preestablished hearing slots; each one is scheduled individually.) The hearing time was recorded on Steve’s recog papers, but wasn’t recorded with the jail’s booking officials, which is standard.

As provided for in the Constitution, everyone has the right to bail out except in a few, extreme cases. In Multnomah County, a defendant may post bail up to 10 minutes before a hearing, although most people post it well before that. Steve posted his three hours and 38 minutes before his first scheduled hearing. District Court was notified immediately. Domestic Relations Court, which actually was slated for the earlier hearing on the restraining-order violation, was informed much later and well after the 1:30 hearing time.

Byerly spent much of the first week after June’s death investigating this ungainly system, and already a few simple changes have helped unsnarl it. Now, Domestic Relations hearings are scheduled and recorded with the jail’s control center. Even if a defendant bails out minutes before, the release officials will have their hearing assignment at hand, and he or she is expected to appear. That means that Steve could still have bailed out of jail at 9:56 am but would still have had to keep his 1:30 pm Domestic Relations hearing time. The assault charge, though, would still have been set over a week because of that court’s overload.

There have been calls from some quarters to institute a system requiring the jail to notify spouses and their lawyers when a prisoner who violates a restraining order posts bail, even if this means the violator is detained for some hours after bail has been provided. Justice Services Administrator Larry Craig is skeptical of the plan, worrying that it amounts to a form of preventive detention heretofore rejected as unconstitutional. He says the system might also place the county in a position of legal responsibility should the jail not be able to reach a spouse and should the released person then harm him or her. Despite his misgivings. Craig has submitted the suggestion to the county’s legal counsel for an opinion and recommendation, which is expected soon. What is needed, in Craig’s opinion, is not a holding tank for bailed suspects, but more money for mental-health counselors to work in the jails with inmates who might endanger themselves or their families once they were released.

Finally, even with the tangle in the jail straightened out and even with the most careful attention to threatening inmates, few people, including Byerly, believe that much can be done to help deteriorated domestic situations without vastly overstepping personal rights. Jail officials reviewed the Irwin situation; the supervisor of the Recognizance Unit, William Wood, summarized it. “Unfortunately, the murder-suicide incident was beyond the control of the criminal-justice system. As long as Mr. Irwin was able to bail, no scheduling procedure could have directly altered his apparent intent . . . to ultimately do bodily harm to Mrs. Irwin. Citizens are allowed certain rights in our society . . . all citizens and the criminal-justice system must assume certain risks. These risks sometimes have tragic results.”