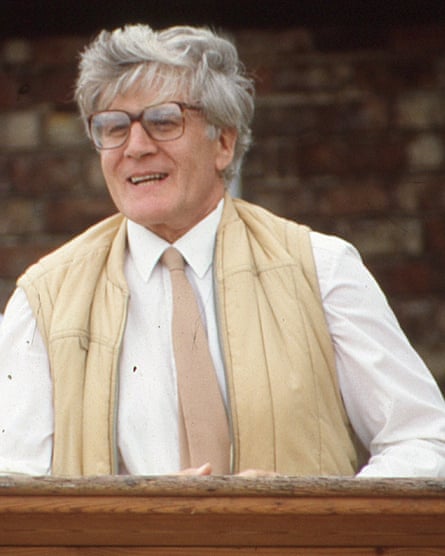

The history of the landscape was a new interest of the 1950s, though initially based on simple and rather superficial observations. The landscape archaeologist Christopher Taylor, who has died aged 85, developed methods that enabled deeper understanding of changes in the countryside, and transformed understanding of villages, manor houses, gardens and castles.

An important source of information for landscape historians came from earthworks visible in the field – hollows and mounds, banks and ditches, moats, terraces and platforms. They represent former roads, boundaries, villages, houses, gardens and fields, but how could the dull and indistinct traces on the ground be understood and interpreted?

One problem was that remains of all periods, from prehistory to the second world war, were jumbled together on the same site. Taylor pioneered the systematic recording of such landscape remains by representing in a precise plan the slopes, depressions and banks visible on the ground. He then subjected the pattern of earthworks to careful analysis, for example separating features of different periods. He did this while working for the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments of England (RCHME, or the Commission, as it was known), where he also trained a generation of researchers in techniques of survey and interpretation.

Bodiam Castle, built around 1385, is a brilliant example of the success of his methods. The castle stands intact now, a square symmetrical structure with towers built along its perimeter walls, straight out of a medieval romance, and with round corner towers that could have contained a Sleeping Beauty.

Modern visitors tend to focus on the building, but the National Trust, which runs the property, asked the Commission in the late 1980s to survey the puzzling banks, ditches and ponds surrounding it. This was undertaken by a small team, supervised by Taylor. By analysing their results, he could envisage how a 15th-century visitor to the castle would have encountered the ponds, terraced gardens and so on, glimpsing the castle as a backdrop.

In 1990 he and members of the team published an article in the journal Medieval Archaeology showing that the earthworks are the surviving clues to “an elaborate and contrived setting”, which was used to guide visitors along routes that gave them dramatic views of the castle “rising out of the moat”. Ordinary ponds, and roads apparently built for practical purposes, were shown to have in fact been promoting the aesthetics of the chivalric ideal.

This interpretation had a role in transforming the perception of castles from grim fortresses to residences that gave aristocrats a pleasurable environment, with gardens as settings for dancing and picnics.

However, Taylor was much more than a diligent civil servant surveying sites according to the Commission’s brief. He was well aware that archaeology and local history attracted the interest of a wide public, and had a strong personal commitment to adult education.

As well as giving talks to adult learners on university extra-mural courses and day schools, he was willing to help amateur groups conduct their own surveys. This led to a series of books aimed mainly at readers with a general interest, including landscape histories of counties he knew well, Cambridgeshire and Dorset. A practical handbook, Fieldwork in Medieval Archaeology (1974), was followed by works on more specialised themes – fields, roads and gardens. The subject of historic gardens was also one that he developed at a time of rising enthusiasm for the subject.

The most important of his books, which attracted readers among both academics and general readers, was Village and Farmstead (1983), based on archaeological fieldwork and excavation, but also close study of maps of existing villages, and aerial photography. It brought together interpretations, and covered a long period, from prehistory to the present day.

Born and brought up in Lichfield in Staffordshire, where his mother, Alice (nee Davis), kept a shop and his father, Richard, was an agricultural engineer, Christopher went from King Edward VI school in Lichfield to the University College of North Staffordshire (now Keele University), where he graduated in history and geography in 1958.

As a student he worked in the summer for the Commission on archaeological fieldwork and, after acquiring a diploma in prehistory at London University, began full-time work at the Commission in 1960, staying until retirement in 1993.

The Commission merged with English Heritage in 1999, but existed for almost a century, charged with compiling inventories of “monuments”. Originally that meant mainly historic buildings, but later included archaeological sites, and Taylor was made head of archaeological survey from 1985.

As an author and as a co-ordinator of the work of others, Taylor was responsible for inventories of sites in Cambridgeshire, Dorset and Northamptonshire, parish by parish, published in a succession of large volumes from the late 60s onwards. These were illustrated with excellent plans and are an imaginative resource for anyone interested in deserted villages, but also as a permanent record of sites that are in constant danger of destruction.

Taylor was active in many academic organisations and societies, and though he did not enjoy committee meetings, he formed many friendships as a result of attending academic gatherings. He was so well liked and admired that he was honoured with three volumes of essays written by friends and colleagues (1997-99). He was also elected a fellow of the British Academy (1995), and in 2013 received the academy’s John Coles medal for his contribution to landscape archaeology. In 1997 he was awarded an honorary doctorate by Keele University.

Taylor married Angela Ballard in 1961. She died in 1983. In 1985 he married Stephanie Ault (nee Spooner). Stephanie survives him, as do his daughter, Katy, and son, Jonathan, from his first marriage, a stepdaughter, Alexandra, and six grandchildren.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion