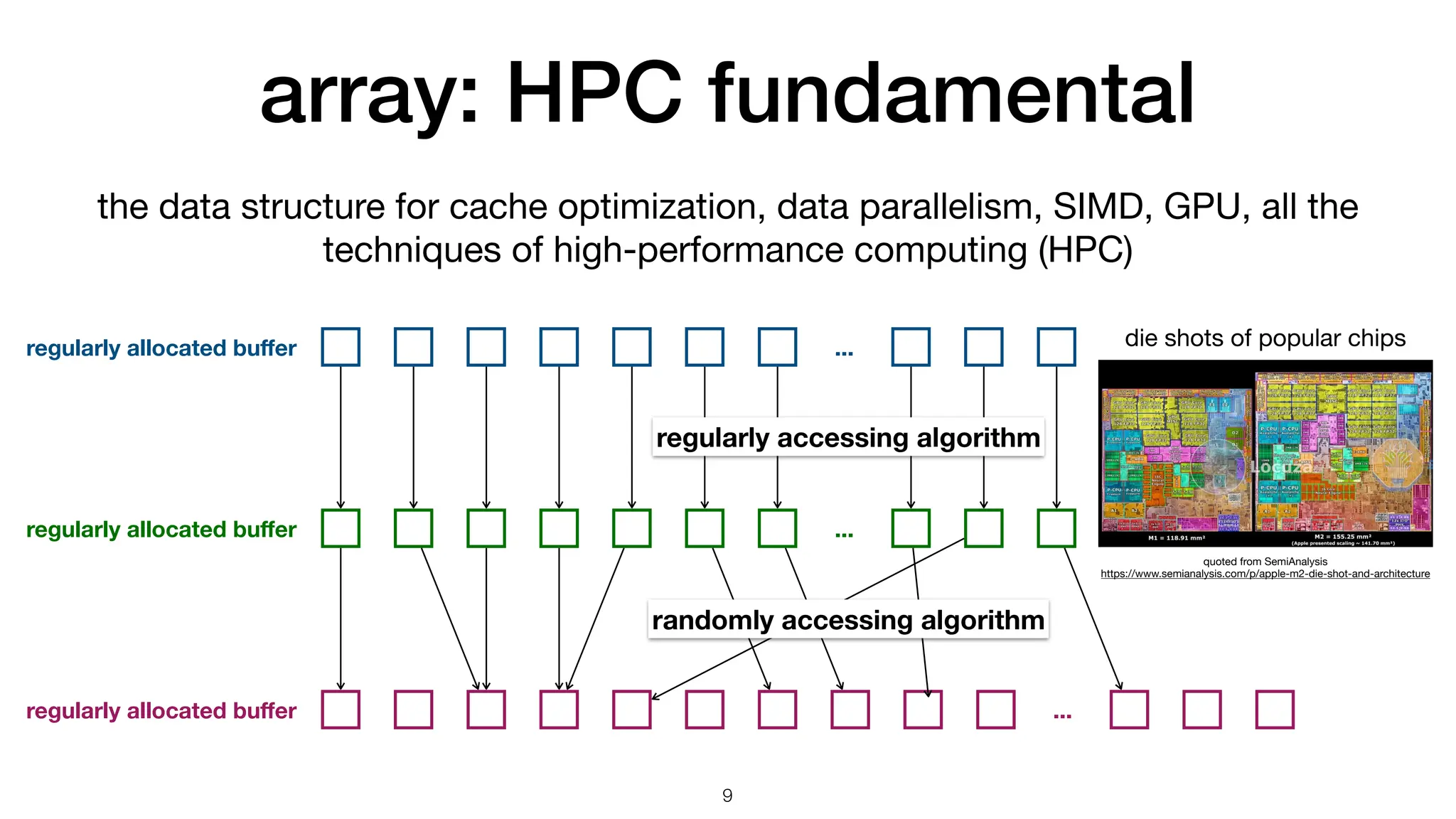

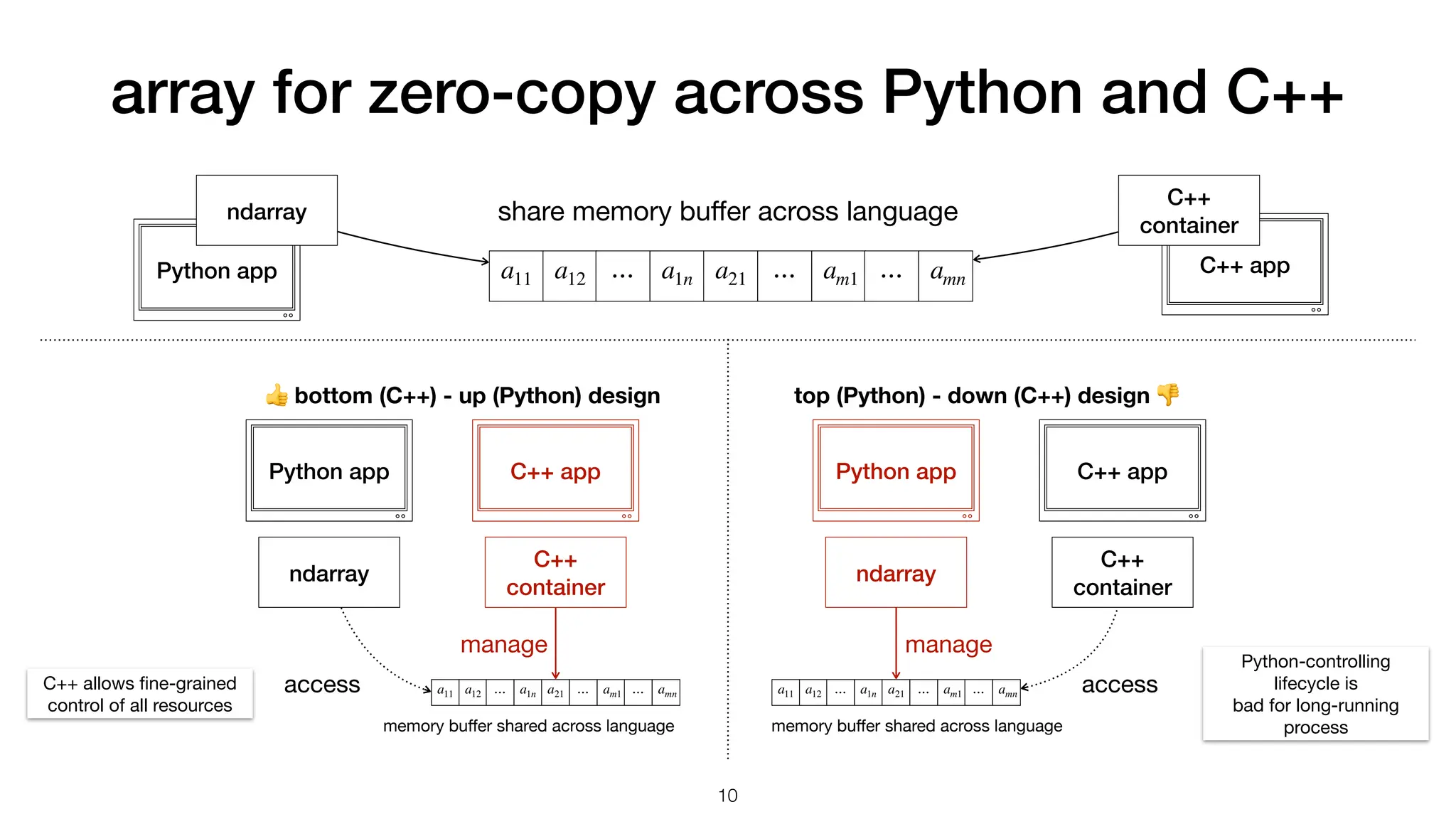

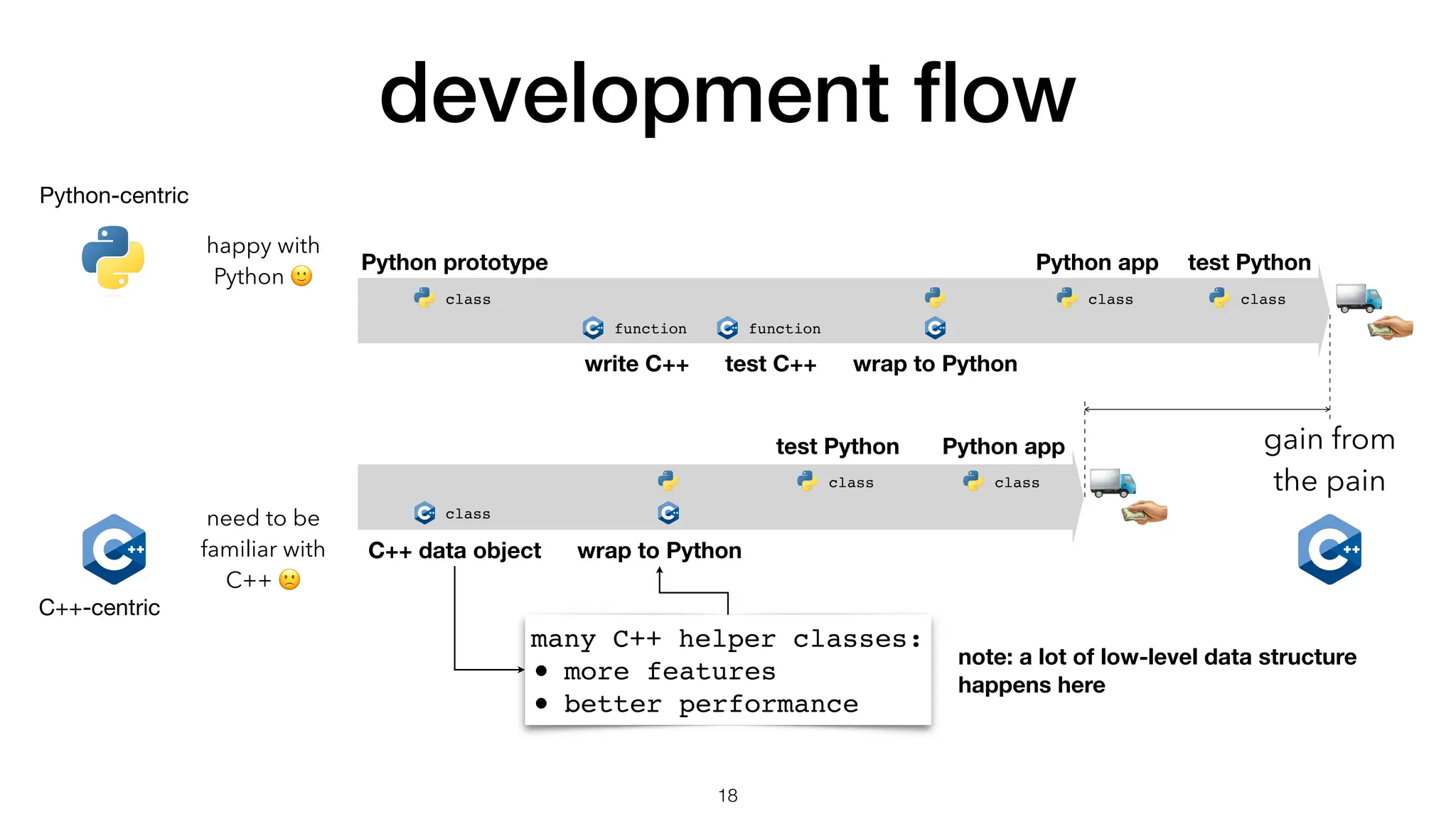

The document discusses the importance of speed in computational methods, particularly in relation to high-speed rail and numerical calculations. It provides an overview of the Point-Jacobi method for solving the Laplace equation, comparing the performance of Python and C++ implementations. It highlights the need for hybrid programming approaches that leverage Python for ease of use while utilizing C++ for performance-critical tasks in high-performance computing.

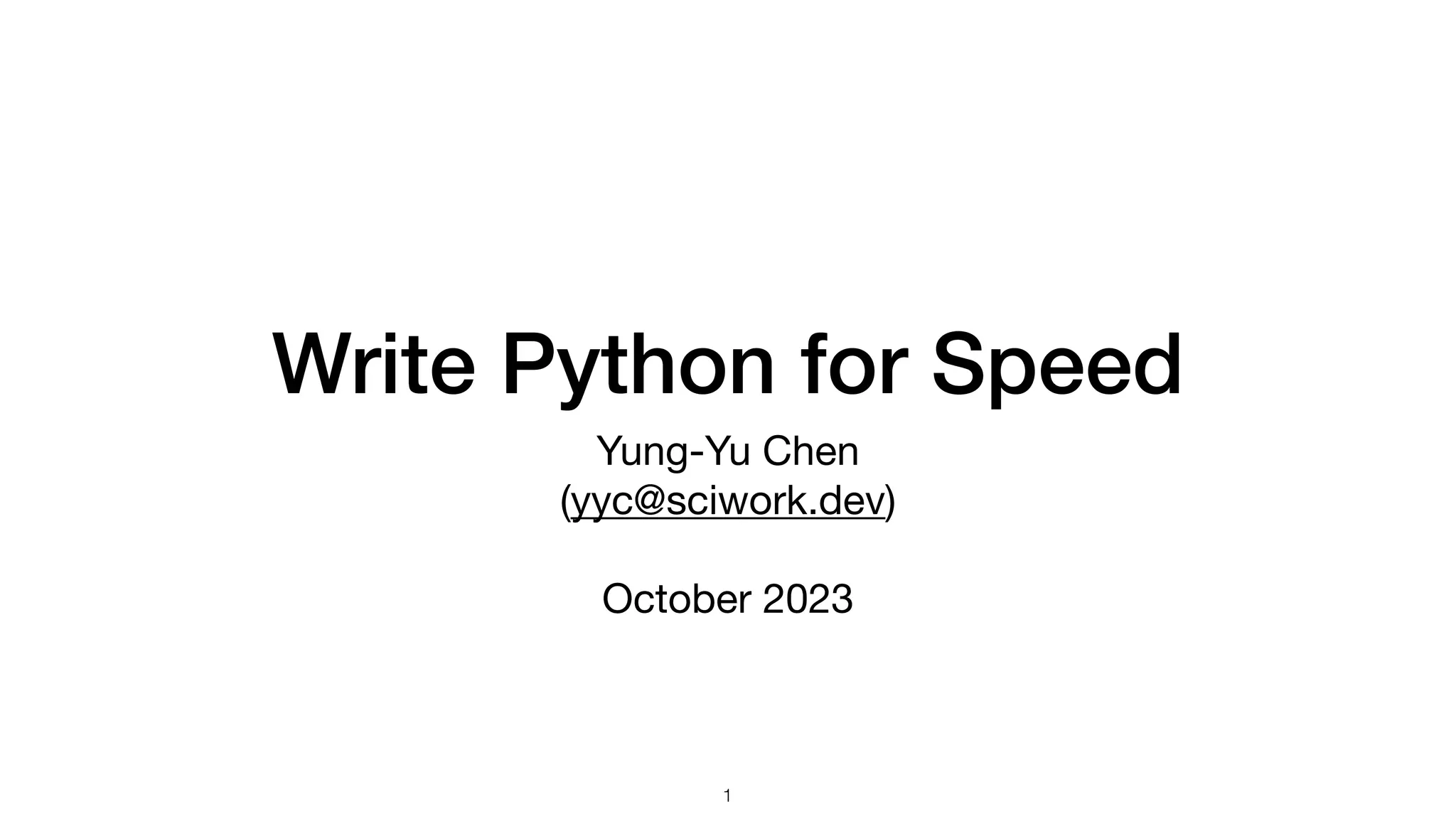

![Python is slow

for it in range(1, nx-1):

for jt in range(1, nx-1):

un[it,jt] = (u[it+1,jt] + u[it-1,jt] + u[it,jt+1] + u[it,jt-1]) / 4

un[1:nx-1,1:nx-1] = (u[2:nx,1:nx-1] + u[0:nx-2,1:nx-1] +

u[1:nx-1,2:nx] + u[1:nx-1,0:nx-2]) / 4

for (size_t it=1; it<nx-1; ++it)

{

for (size_t jt=1; jt<nx-1; ++jt)

{

un(it,jt) = (u(it+1,jt) + u(it-1,jt) + u(it,jt+1) + u(it,jt-1)) / 4;

}

}

Point-Jacobi method

Python nested loop

Numpy array

C++ nested loop

4.797s (1x)

0.055s (87x)

0.025s (192x)

un+1

(xi, yi) =

un

(xi+1, yj) + un

(xi−1, yj) + un

(xi, yj+1) + un

(xi, yj−1)

4

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/writepythonforspeedpyconapac20231027-231028212349-d3988144/75/Write-Python-for-Speed-4-2048.jpg)

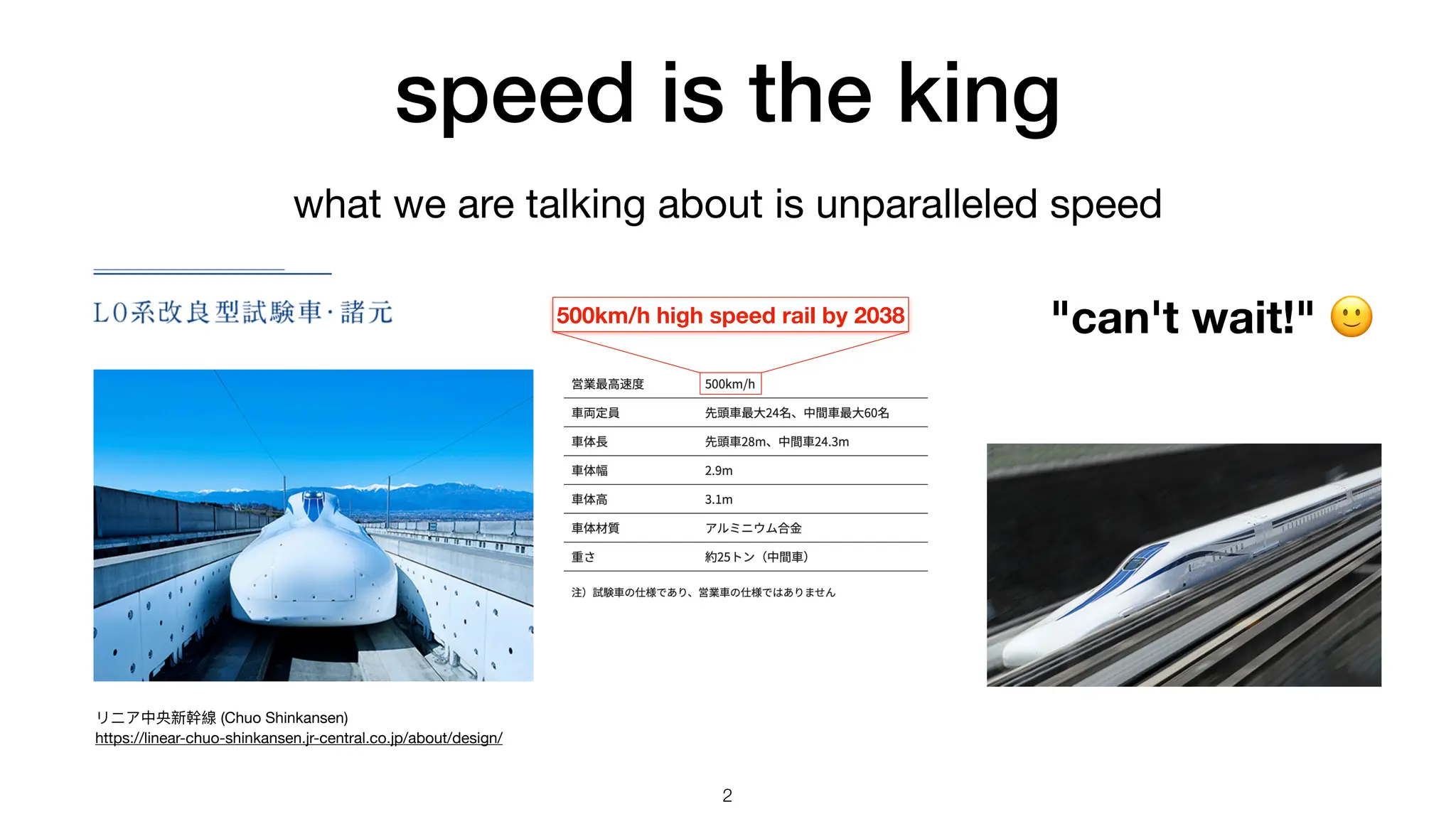

![machine determines speed

void calc_distance(

size_t const n

, double const * x

, double const * y

, double * r)

{

for (size_t i = 0 ; i < n ; ++i)

{

r[i] = std::sqrt(x[i]*x[i] + y[i]*y[i]);

}

}

vmovupd ymm0, ymmword [rsi + r9*8]

vmulpd ymm0, ymm0, ymm0

vmovupd ymm1, ymmword [rdx + r9*8]

vmulpd ymm1, ymm1, ymm1

vaddpd ymm0, ymm0, ymm1

vsqrtpd ymm0, ymm0

movupd xmm0, xmmword [rsi + r8*8]

mulpd xmm0, xmm0

movupd xmm1, xmmword [rdx + r8*8]

mulpd xmm1, xmm1

addpd xmm1, xmm0

sqrtpd xmm0, xmm1

AVX: 256-bit-wide vectorization SSE: 128-bit-wide vectorization

C++ code

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/writepythonforspeedpyconapac20231027-231028212349-d3988144/75/Write-Python-for-Speed-8-2048.jpg)

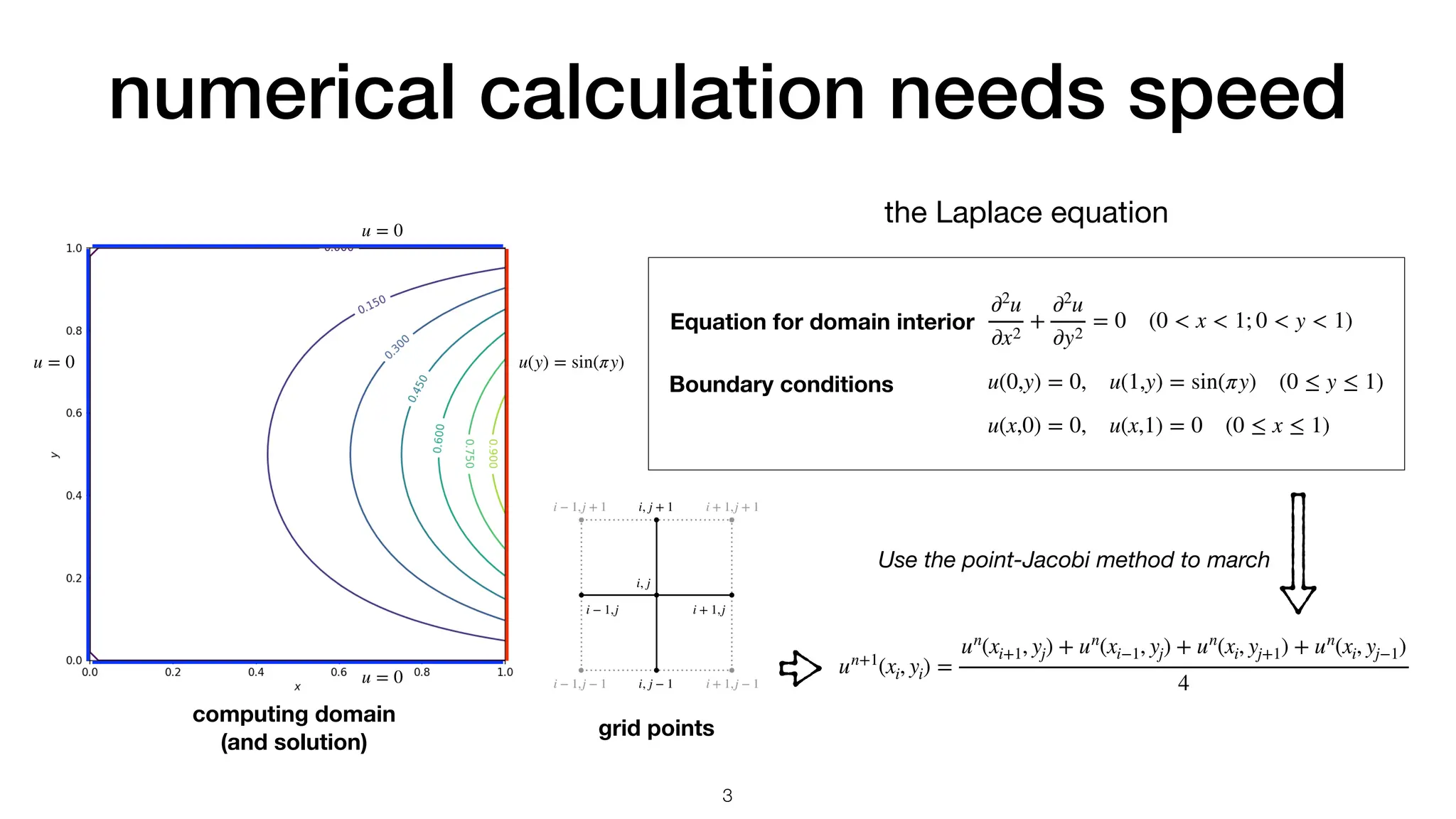

![quick prototype in Python:

something new and fragile

• thread pool for I/O? certainly

Python

• certainly not want to write

complicated C++ to prototype

• 64 threads on 32-core servers?

• consider to move it to C++

• data-parallel code on top of the

thread pool?

• time to go with TBB (thread-

building block) C++ library

from _thread import allocate_lock, start_new_thread

class ThreadPool(object):

"""Python prototype for I/O thread pool"""

def __init__(self, nthread):

# Worker callback

self.func = None

# Placeholders for managing data

self.__threadids = [None] * nthread

self.__threads = [None] * nthread

self.__returns = [None] * nthread

# Initialize thread managing data

for it in range(nthread):

mlck = allocate_lock(); mlck.acquire()

wlck = allocate_lock(); wlck.acquire()

tdata = [mlck, wlck, None, None]

self.__threads[it] = tdata

tid = start_new_thread(self.eventloop, (tdata,))

self.__threadids[it] = tid

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/writepythonforspeedpyconapac20231027-231028212349-d3988144/75/Write-Python-for-Speed-11-2048.jpg)

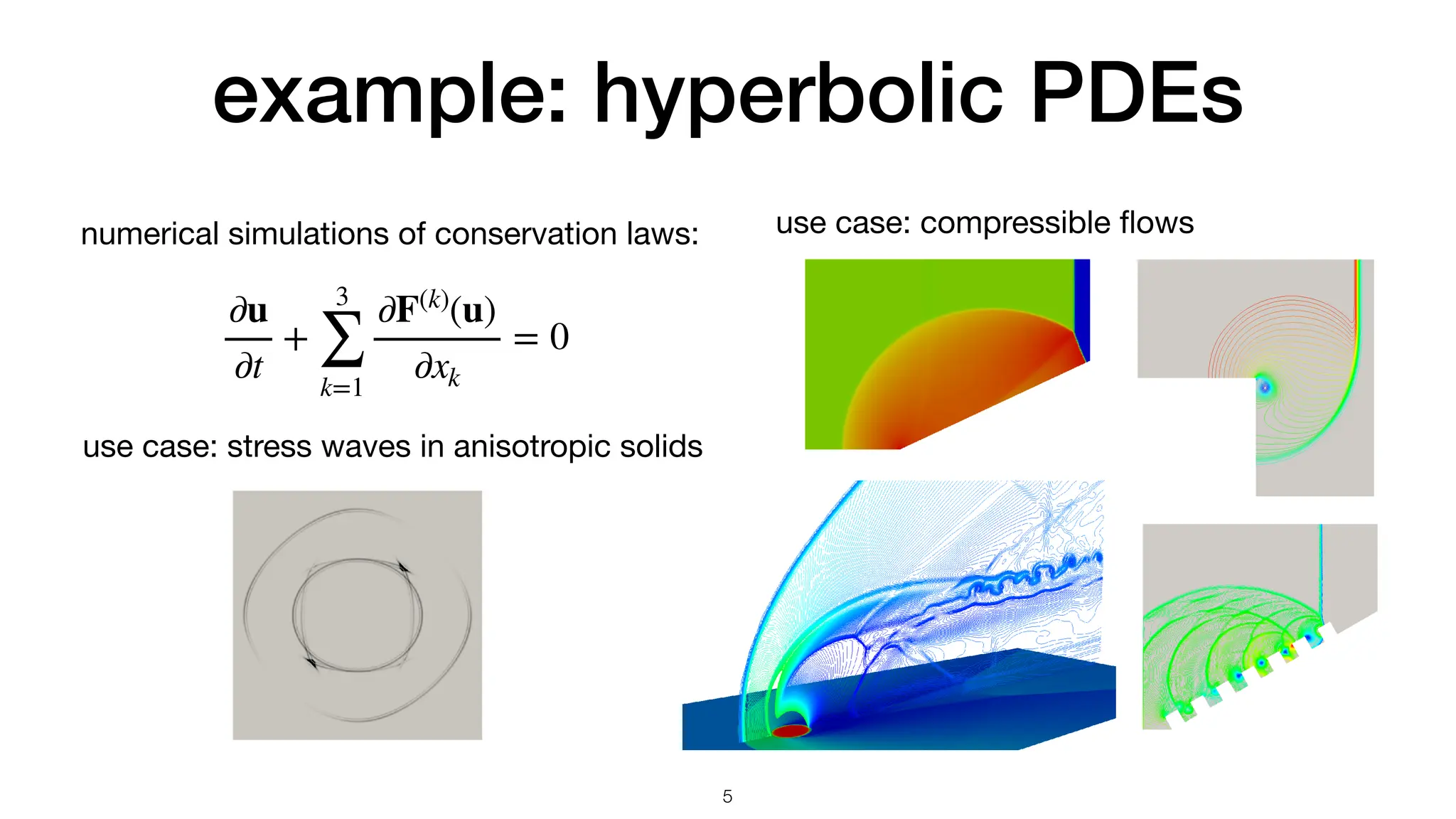

![quick prototype in Python:

something complex

i, j

i, j + 1

i, j − 1

i + 1,j

i − 1,j

i + 1,j + 1

i + 1,j − 1

i − 1,j + 1

i − 1,j − 1

di

ff

erence equation

def solve_python_loop():

u = uoriginal.copy() # Input from outer scope

un = u.copy() # Create the buffer for the next time step

converged = False

step = 0

# Outer loop.

while not converged:

step += 1

# Inner loops. One for x and the other for y.

for it in range(1, nx-1):

for jt in range(1, nx-1):

un[it,jt] = (u[it+1,jt] + u[it-1,jt] + u[it,jt+1] + u[it,jt-1]) / 4

norm = np.abs(un-u).max()

u[...] = un[...]

converged = True if norm < 1.e-5 else False

return u, step, norm

12

grid points

python nested loop implementing point-Jacobi method

u(xi, yj) =

u(xi+1, yj) + u(xi−1, yj) + u(xi, yj+1) + u(xi, yj−1)

4

point-Jacobi method

un+1

(xi, yi) =

un

(xi+1, yj) + un

(xi−1, yj) + un

(xi, yj+1) + un

(xi, yj−1)

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/writepythonforspeedpyconapac20231027-231028212349-d3988144/75/Write-Python-for-Speed-12-2048.jpg)

![production: many data many ways

13

fi

t scattered points to a polynomial

f(x) = a3x3

+ a2x2

+ a1x + a0

test many (like 1,000+) such data sets:

def plot_poly_fitted(i):

slct = (xdata>=i)&(xdata<(i+1))

sub_x = xdata[slct]

sub_y = ydata[slct]

poly = data_prep.fit_poly(sub_x, sub_y, 3)

print(poly)

poly = np.poly1d(poly)

xp = np.linspace(sub_x.min(), sub_x.max(), 100)

plt.plot(sub_x, sub_y, '.', xp, poly(xp), '-')

plot_poly_fitted(10)

(yeah, the data points seem to be too random to be represented by a polynomial)

// The rank of the linear map is (order+1).

modmesh::SimpleArray<double> matrix(std::vector<size_t>{order+1, order+1});

// Use the x coordinates to build the linear map for least-square

// regression.

for (size_t it=0; it<order+1; ++it)

{

for (size_t jt=0; jt<order+1; ++jt)

{

double & val = matrix(it, jt);

val = 0;

for (size_t kt=start; kt<stop; ++kt)

{

val += pow(xarr[kt], it+jt);

}

}

}

>>> with Timer():

>>> # Do the calculation for the 1000 groups of points.

>>> polygroup = np.empty((1000, 3), dtype='float64')

>>> for i in range(1000):

>>> # Use numpy to build the point group.

>>> slct = (xdata>=i)&(xdata<(i+1))

>>> sub_x = xdata[slct]

>>> sub_y = ydata[slct]

>>> polygroup[i,:] = data_prep.fit_poly(sub_x, sub_y, 2)

>>> with Timer():

>>> # Using numpy to build the point groups takes a lot of time.

>>> data_groups = []

>>> for i in range(1000):

>>> slct = (xdata>=i)&(xdata<(i+1))

>>> data_groups.append((xdata[slct], ydata[slct]))

>>> with Timer():

>>> # Fitting helper runtime is much less than building the point groups.

>>> polygroup = np.empty((1000, 3), dtype='float64')

>>> for it, (sub_x, sub_y) in enumerate(data_groups):

>>> polygroup[it,:] = data_prep.fit_poly(sub_x, sub_y, 2)

Wall time: 1.49671 s

Wall time: 1.24653 s

Wall time: 0.215859 s

prepare data

fi

t polynomials](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/writepythonforspeedpyconapac20231027-231028212349-d3988144/75/Write-Python-for-Speed-13-2048.jpg)

![problem of speedup

14

>>> with Timer():

>>> # Using numpy to build the point groups takes a lot of time.

>>> data_groups = []

>>> for i in range(1000):

>>> slct = (xdata>=i)&(xdata<(i+1))

>>> data_groups.append((xdata[slct], ydata[slct]))

Wall time: 1.24653 s

>>> with Timer():

>>> # Fitting helper runtime is much less than building the point groups.

>>> polygroup = np.empty((1000, 3), dtype='float64')

>>> for it, (sub_x, sub_y) in enumerate(data_groups):

>>> polygroup[it,:] = data_prep.fit_poly(sub_x, sub_y, 2)

Wall time: 0.215859 s

>>> with Timer():

>>> rbatch = data_prep.fit_polys(xdata, ydata, 2)

Wall time: 0.21058 s

/**

* This function calculates the least-square regression of multiple sets of

* point clouds to the corresponding polynomial functions of a given order.

*/

modmesh::SimpleArray<double> fit_polys

(

modmesh::SimpleArray<double> const & xarr

, modmesh::SimpleArray<double> const & yarr

, size_t order

)

{

size_t xmin = std::floor(*std::min_element(xarr.begin(), xarr.end()));

size_t xmax = std::ceil(*std::max_element(xarr.begin(), xarr.end()));

size_t ninterval = xmax - xmin;

modmesh::SimpleArray<double> lhs(std::vector<size_t>{ninterval, order+1});

std::fill(lhs.begin(), lhs.end(), 0); // sentinel.

size_t start=0;

for (size_t it=0; it<xmax; ++it)

{

// NOTE: We take advantage of the intrinsic features of the input data

// to determine the grouping. This is ad hoc and hard to maintain. We

// play this trick to demonstrate a hackish way of performing numerical

// calculation.

size_t stop;

for (stop=start; stop<xarr.size(); ++stop)

{

if (xarr[stop]>=it+1) { break; }

}

// Use the single polynomial helper function.

auto sub_lhs = fit_poly(xarr, yarr, start, stop, order);

for (size_t jt=0; jt<order+1; ++jt)

{

lhs(it, jt) = sub_lhs[jt];

}

start = stop;

}

return lhs;

}

prepare data and loop in Python:

prepare data and loop in C++:

C++ wins so much, but we lose

fl

exibility!

// NOTE: We take advantage of the intrinsic features of the input data

// to determine the grouping. This is ad hoc and hard to maintain. We

// play this trick to demonstrate a hackish way of performing numerical

// calculation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/writepythonforspeedpyconapac20231027-231028212349-d3988144/75/Write-Python-for-Speed-14-2048.jpg)

-> decltype(auto)

{ return self.NAME(); })

(*this)

// geometry arrays

MM_DECL_ARRAY(ndcrd)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(fccnd)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(fcnml)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(fcara)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(clcnd)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(clvol)

// meta arrays

MM_DECL_ARRAY(fctpn)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(cltpn)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(clgrp)

// connectivity arrays

MM_DECL_ARRAY(fcnds)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(fccls)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(clnds)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(clfcs)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(ednds);

#undef MM_DECL_ARRAY

# Construct the data object

mh = modmesh.StaticMesh(

ndim=3, nnode=4, nface=4, ncell=1)

# Set the data

mh.ndcrd.ndarray[:, :] =

(0, 0, 0), (0, 1, 0), (-1, 1, 0), (0, 1, 1)

mh.cltpn.ndarray[:] = modmesh.StaticMesh.TETRAHEDRON

mh.clnds.ndarray[:, :5] = [(4, 0, 1, 2, 3)]

# Calculate internal by the input data

# to build up the object

mh.build_interior()

np.testing.assert_almost_equal(

mh.fccnd,

[[-0.3333333, 0.6666667, 0. ],

[ 0. , 0.6666667, 0.3333333],

[-0.3333333, 0.6666667, 0.3333333],

[-0.3333333, 1. , 0.3333333]])

mesh shape information

data arrays

data arrays will be very large: gigabytes in memory

use data in python

C++ library pybind11 wrapper

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/writepythonforspeedpyconapac20231027-231028212349-d3988144/75/Write-Python-for-Speed-16-2048.jpg)

![test in Python

def test_2d_trivial_triangles(self):

mh = modmesh.StaticMesh(ndim=2, nnode=4, nface=0, ncell=3)

mh.ndcrd.ndarray[:, :] = (0, 0), (-1, -1), (1, -1), (0, 1)

mh.cltpn.ndarray[:] = modmesh.StaticMesh.TRIANGLE

mh.clnds.ndarray[:, :4] = (3, 0, 1, 2), (3, 0, 2, 3), (3, 0, 3, 1)

self._check_shape(mh, ndim=2, nnode=4, nface=0, ncell=3,

nbound=0, ngstnode=0, ngstface=0, ngstcell=0,

nedge=0)

# Test build interior data.

mh.build_interior(_do_metric=False, _build_edge=False)

self._check_shape(mh, ndim=2, nnode=4, nface=6, ncell=3,

nbound=0, ngstnode=0, ngstface=0, ngstcell=0,

nedge=0)

mh.build_interior() # _do_metric=True, _build_edge=True

self._check_shape(mh, ndim=2, nnode=4, nface=6, ncell=3,

nbound=0, ngstnode=0, ngstface=0, ngstcell=0,

nedge=6)

np.testing.assert_almost_equal(

mh.fccnd,

[[-0.5, -0.5], [0.0, -1.0], [0.5, -0.5],

[0.5, 0.0], [0.0, 0.5], [-0.5, 0.0]])

np.testing.assert_almost_equal(

mh.fcnml,

[[-0.7071068, 0.7071068], [0.0, -1.0], [0.7071068, 0.7071068],

[0.8944272, 0.4472136], [-1.0, -0.0], [-0.8944272, 0.4472136]])

np.testing.assert_almost_equal(

mh.fcara, [1.4142136, 2.0, 1.4142136, 2.236068, 1.0, 2.236068])

np.testing.assert_almost_equal(

mh.clcnd, [[0.0, -0.6666667], [0.3333333, 0.0], [-0.3333333, 0.0]])

np.testing.assert_almost_equal(

mh.clvol, [1.0, 0.5, 0.5])

17

namespace py = pybind11;

(*this)

// shape data

.def_property_readonly("ndim", &wrapped_type::ndim)

.def_property_readonly("nnode", &wrapped_type::nnode)

.def_property_readonly("nface", &wrapped_type::nface)

.def_property_readonly("ncell", &wrapped_type::ncell)

.def_property_readonly("nbound", &wrapped_type::nbound)

.def_property_readonly("ngstnode", &wrapped_type::ngstnode)

.def_property_readonly("ngstface", &wrapped_type::ngstface)

.def_property_readonly("ngstcell", &wrapped_type::ngstcell)

#define MM_DECL_ARRAY(NAME) .expose_SimpleArray(

#NAME,

[](wrapped_type & self) -> decltype(auto){ return self.NAME(); })

(*this)

// geometry arrays

MM_DECL_ARRAY(ndcrd)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(fccnd)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(fcnml)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(fcara)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(clcnd)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(clvol)

// meta arrays

MM_DECL_ARRAY(fctpn)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(cltpn)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(clgrp)

// connectivity arrays

MM_DECL_ARRAY(fcnds)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(fccls)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(clnds)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(clfcs)

MM_DECL_ARRAY(ednds);

#undef MM_DECL_ARRAY

wrapping to Python enables fast testing development may be done as writing tests!

# Construct the data object

mh = modmesh.StaticMesh(

ndim=3, nnode=4, nface=4, ncell=1)

# Set the data

mh.ndcrd.ndarray[:, :] =

(0, 0, 0), (0, 1, 0), (-1, 1, 0), (0, 1, 1)

mh.cltpn.ndarray[:] = modmesh.StaticMesh.TETRAHEDRON

mh.clnds.ndarray[:, :5] = [(4, 0, 1, 2, 3)]

# Calculate internal by the input data

# to build up the object

mh.build_interior()

np.testing.assert_almost_equal(

mh.fccnd,

[[-0.3333333, 0.6666667, 0. ],

[ 0. , 0.6666667, 0.3333333],

[-0.3333333, 0.6666667, 0.3333333],

[-0.3333333, 1. , 0.3333333]])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/writepythonforspeedpyconapac20231027-231028212349-d3988144/75/Write-Python-for-Speed-17-2048.jpg)

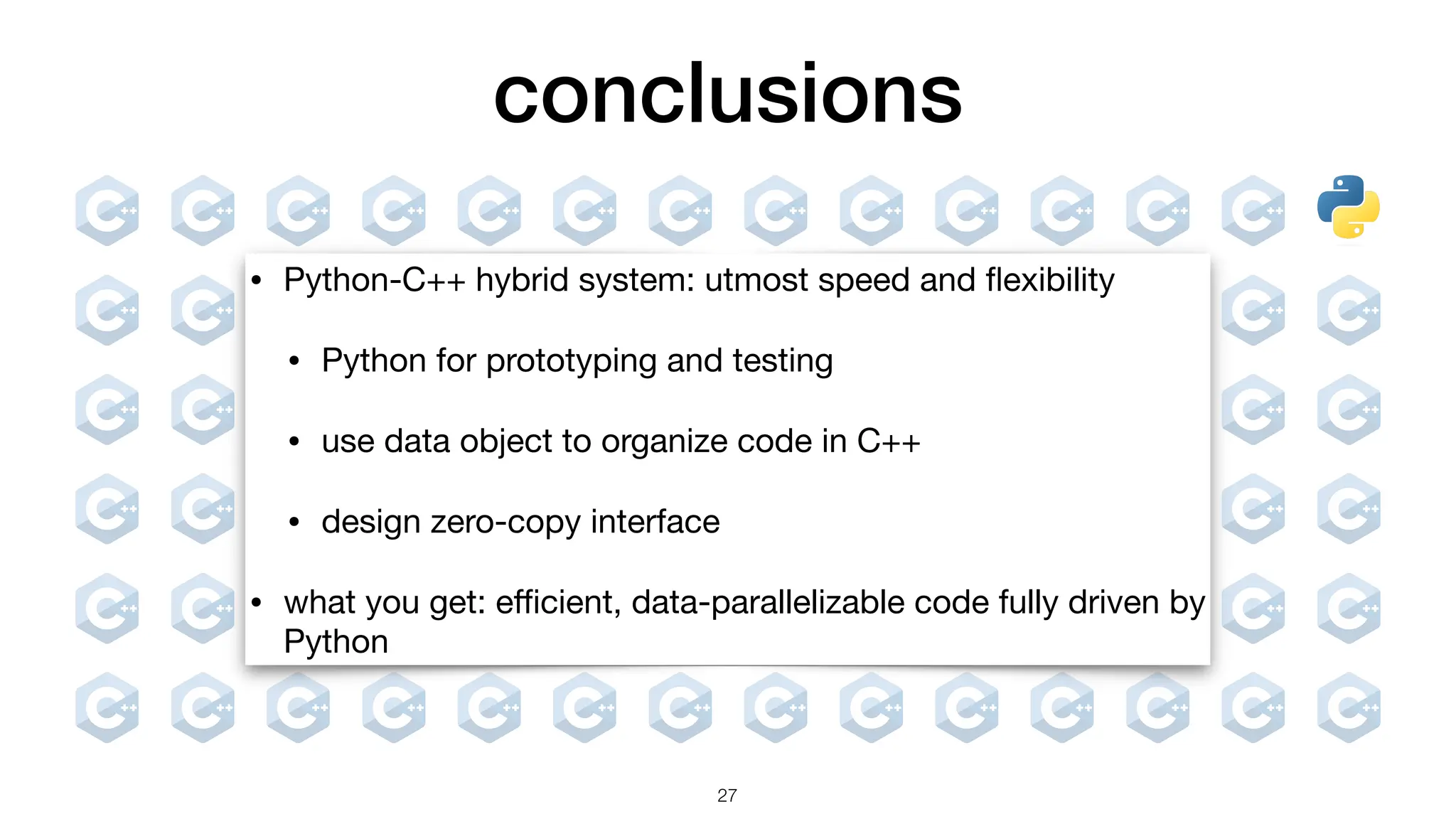

![develop SimpleArray in C++

SimpleArray std::vector

SimpleArray is

fi

xed size 👍

• only allocate memory on

construction

std::vector is variable size 👎

• bu

ff

er may be invalidated

• implicit memory allocation

(reallocation)

multi-dimensional access 👍

operator()

one-dimensional access 👎

operator[]

19

C++

container

ndarray

manage

access a11 a12 ⋯ a1n a21 ⋯ am1 ⋯ amn

memory bu

ff

er

make it yourself get it free from STL](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/writepythonforspeedpyconapac20231027-231028212349-d3988144/75/Write-Python-for-Speed-19-2048.jpg)