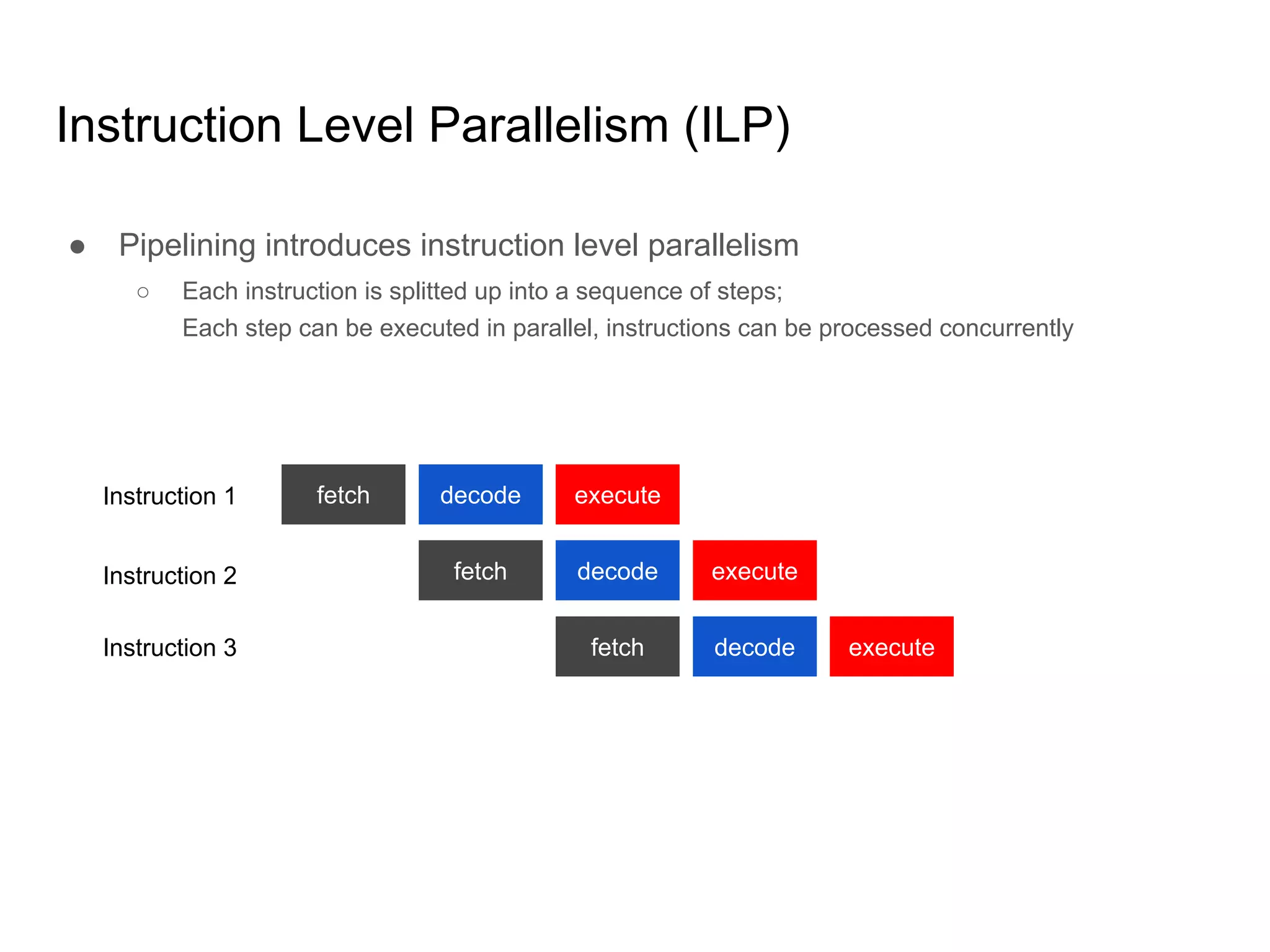

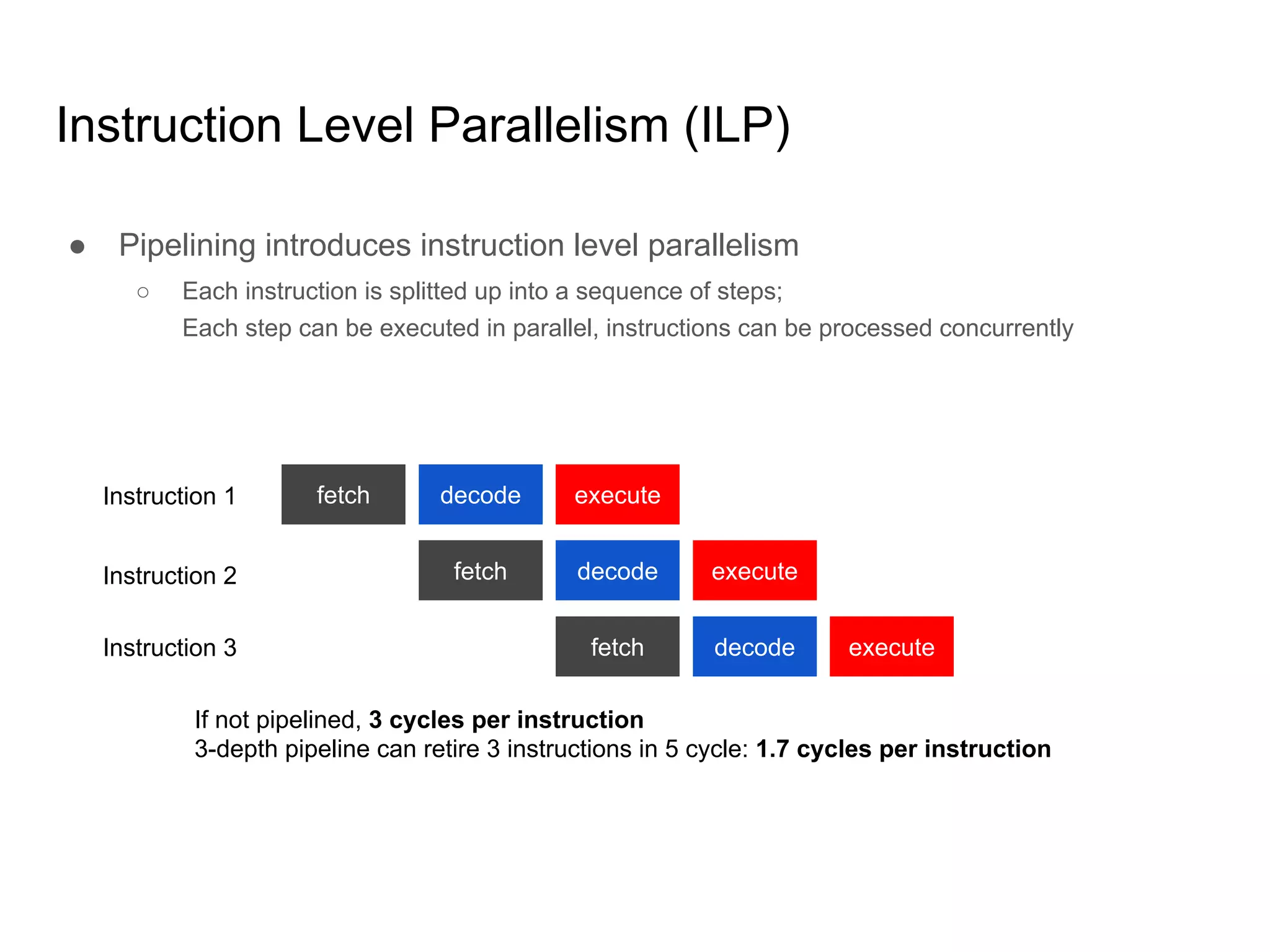

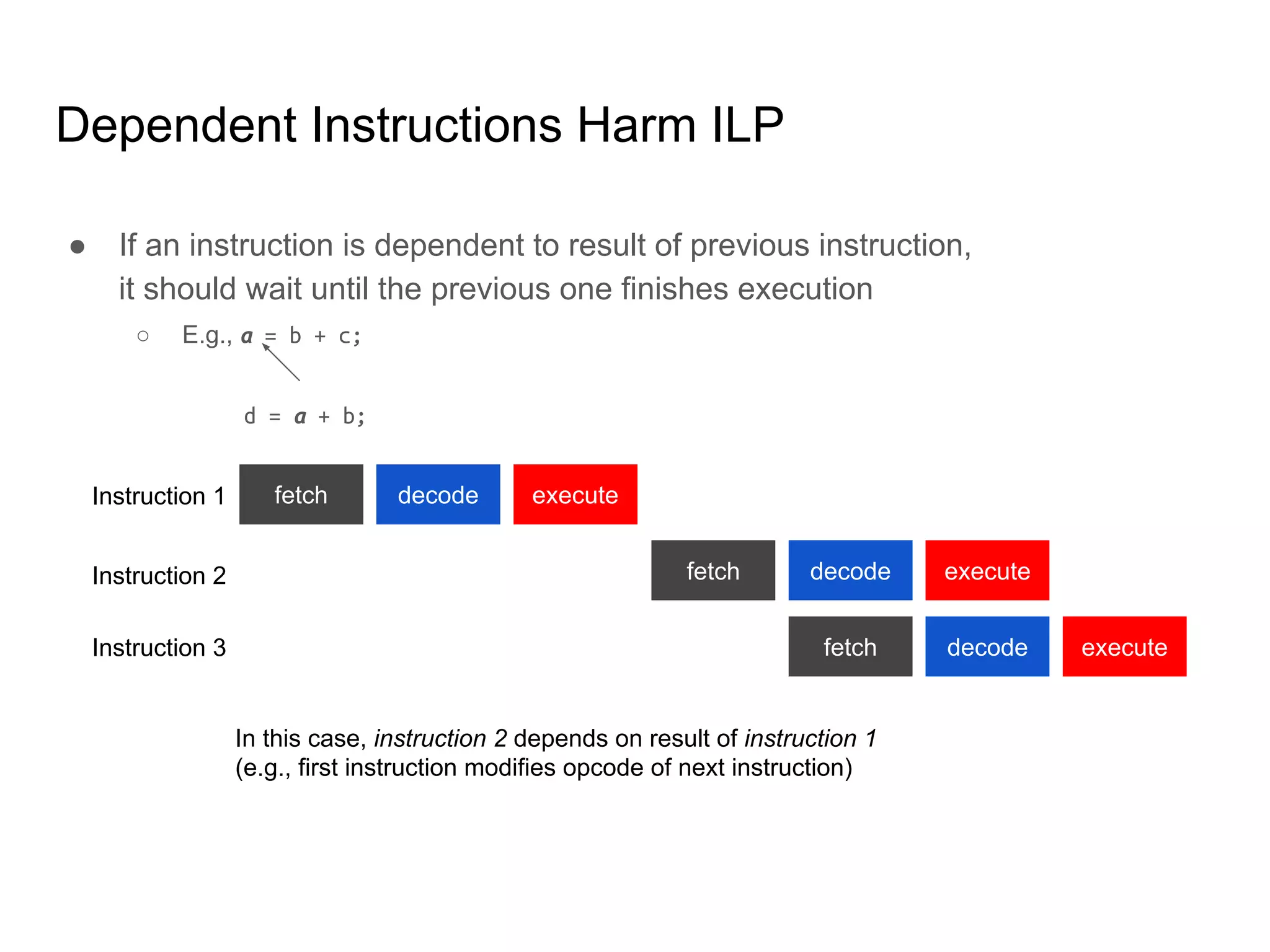

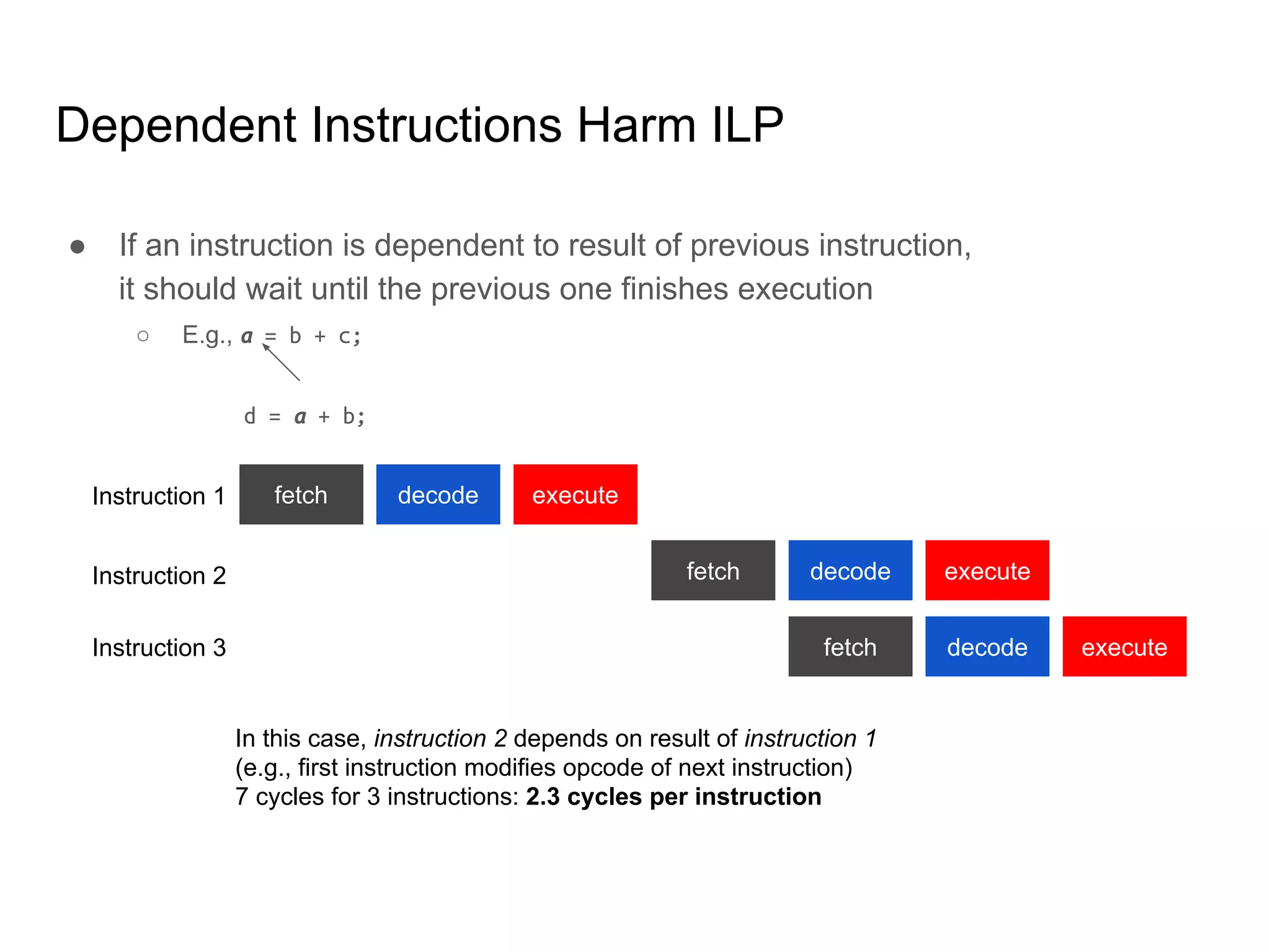

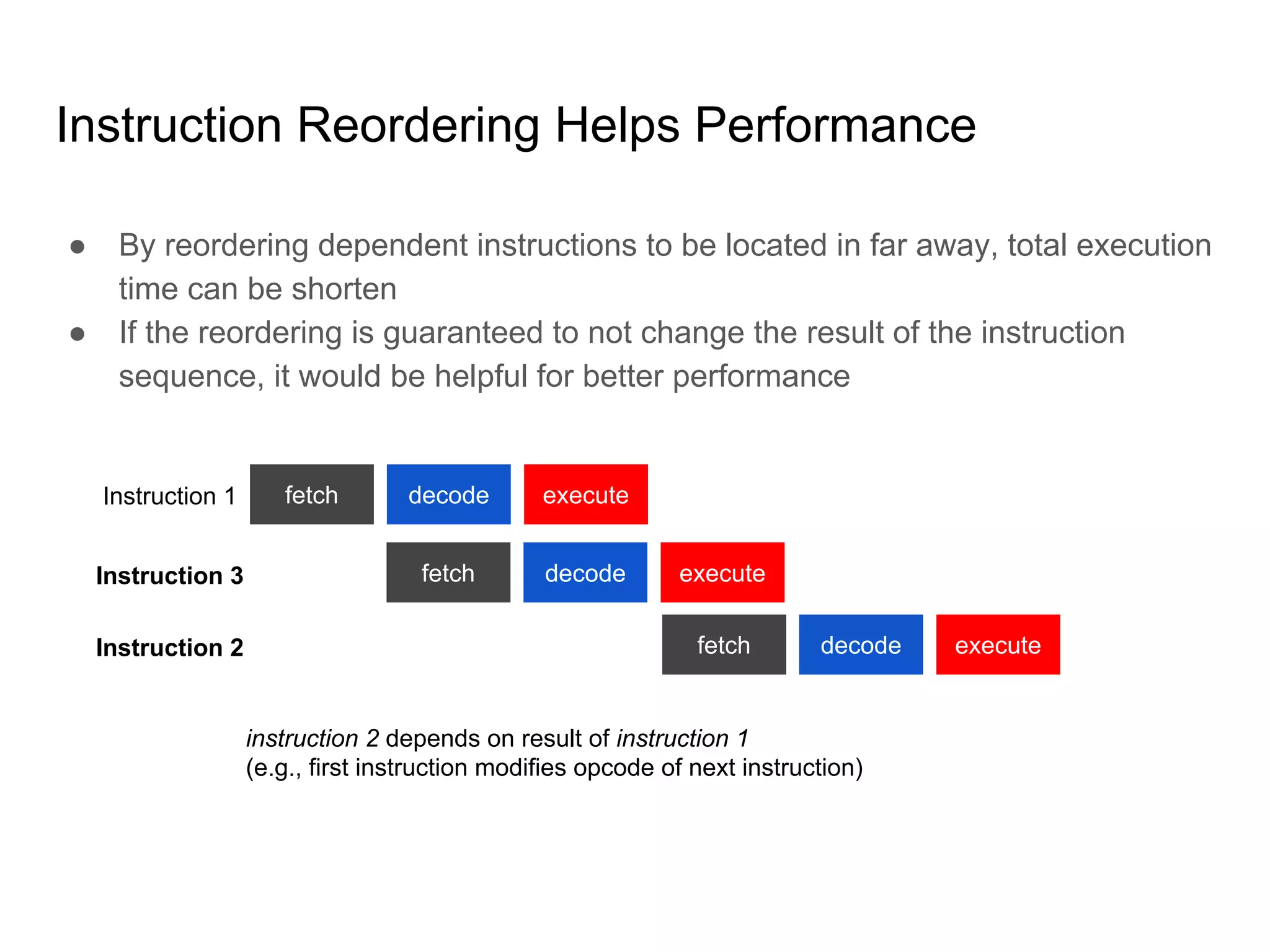

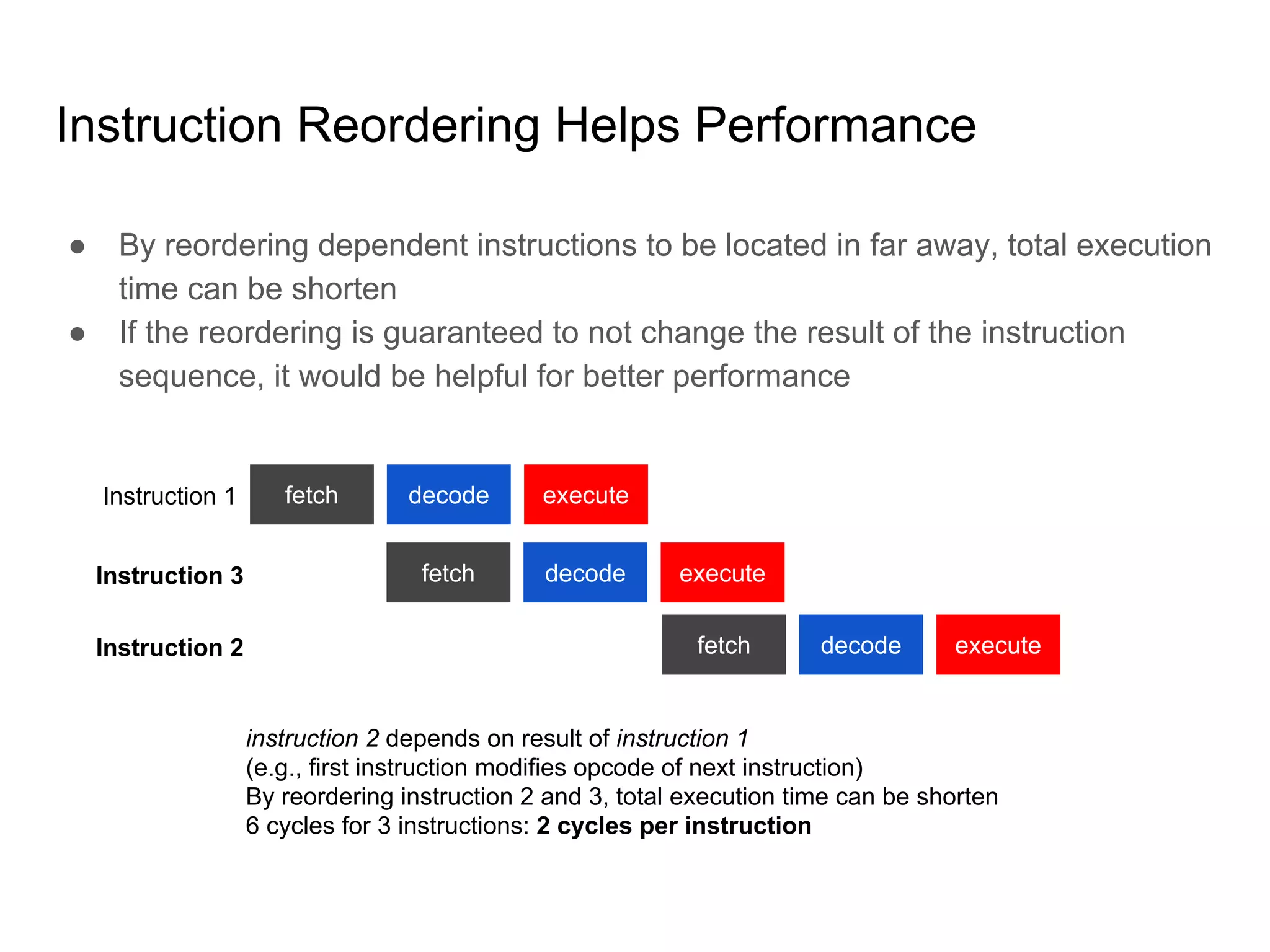

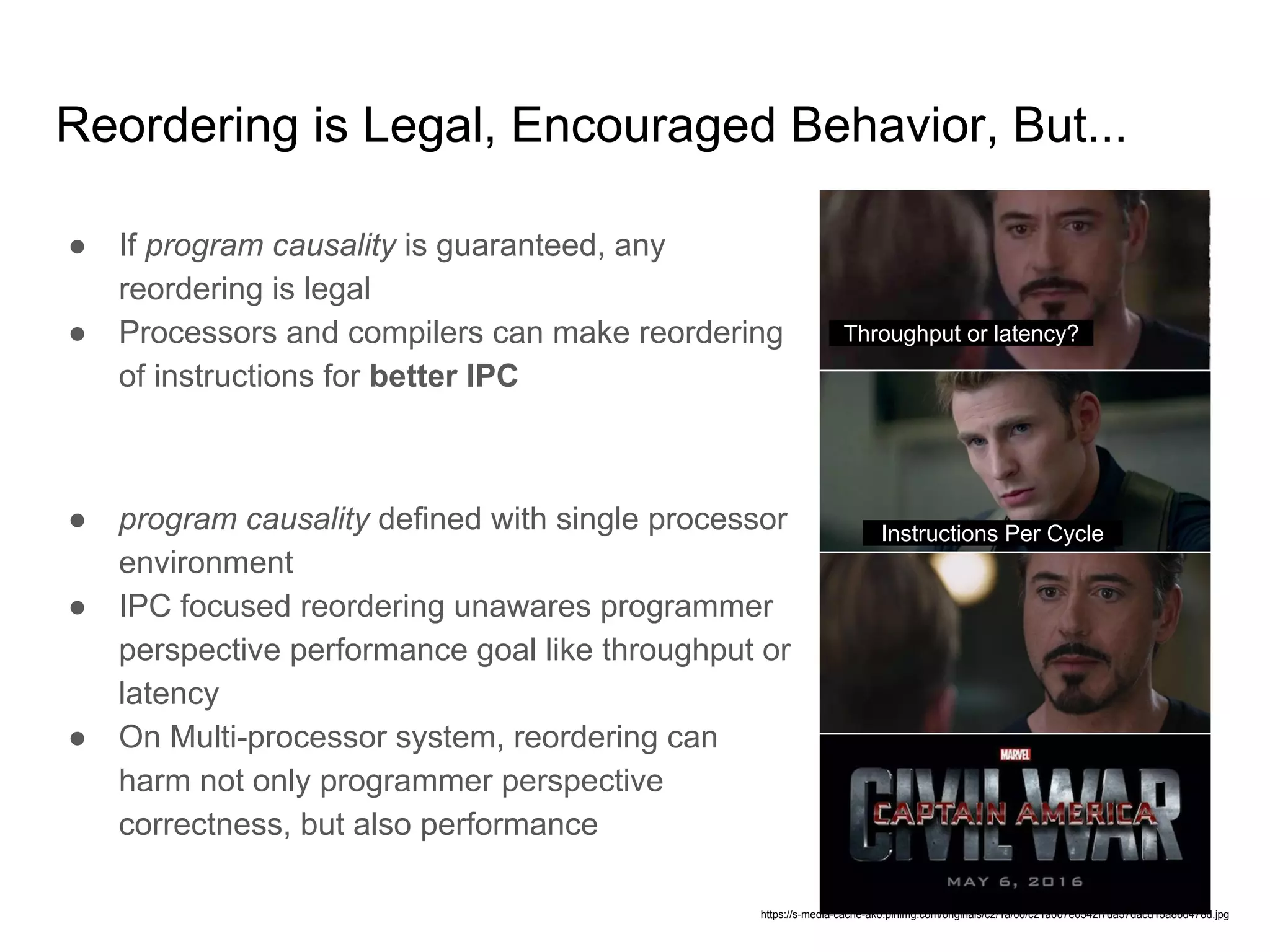

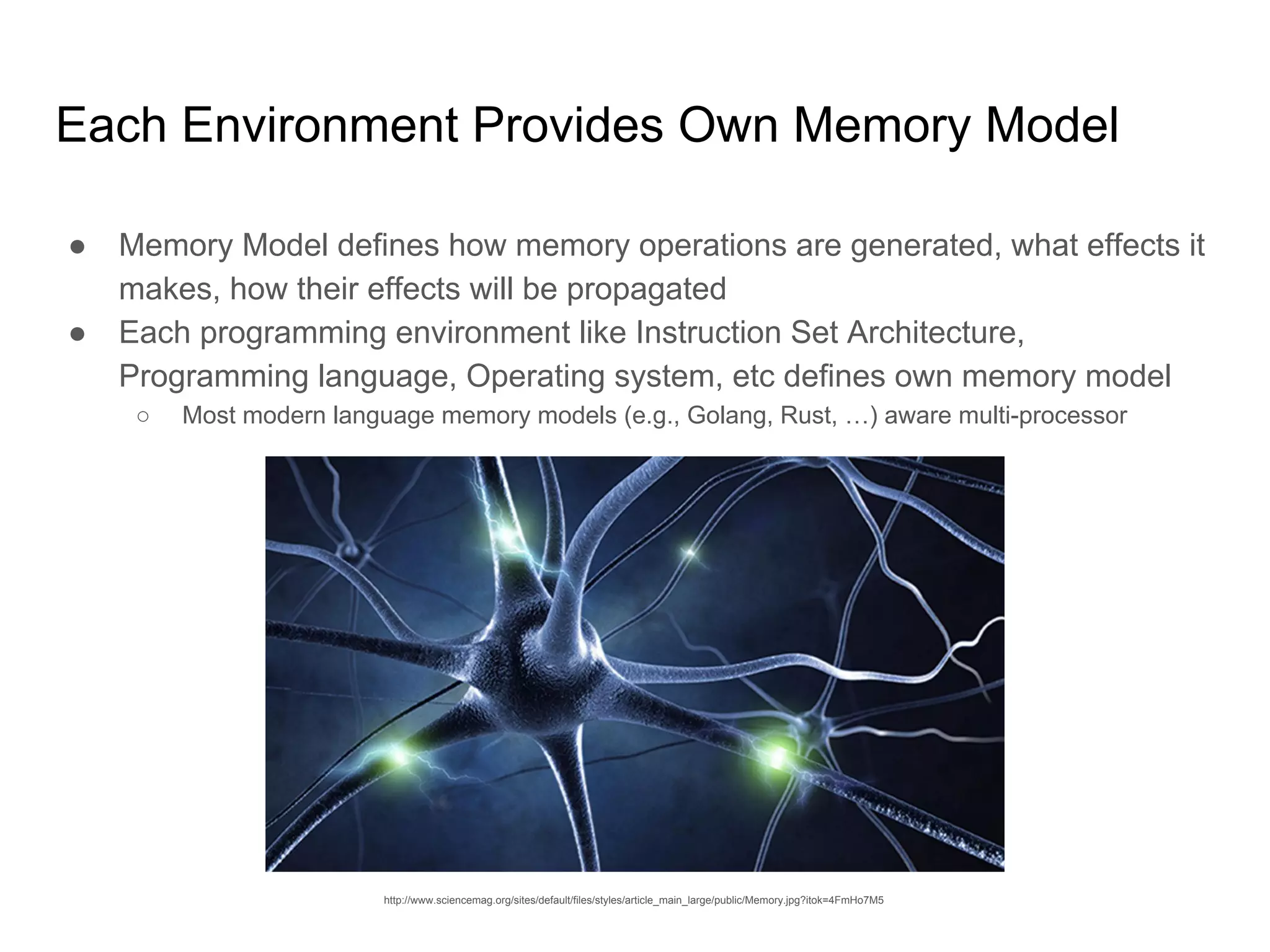

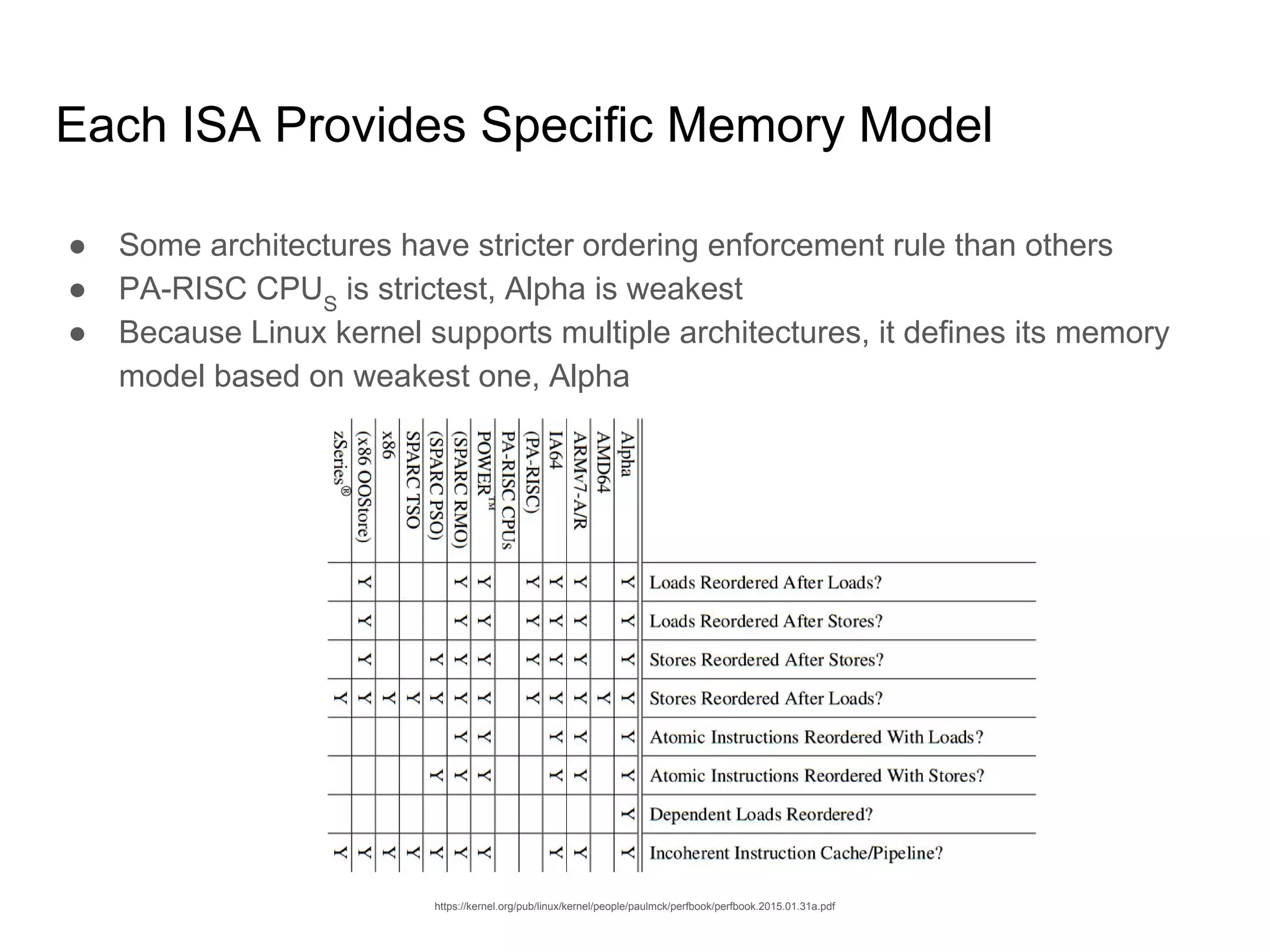

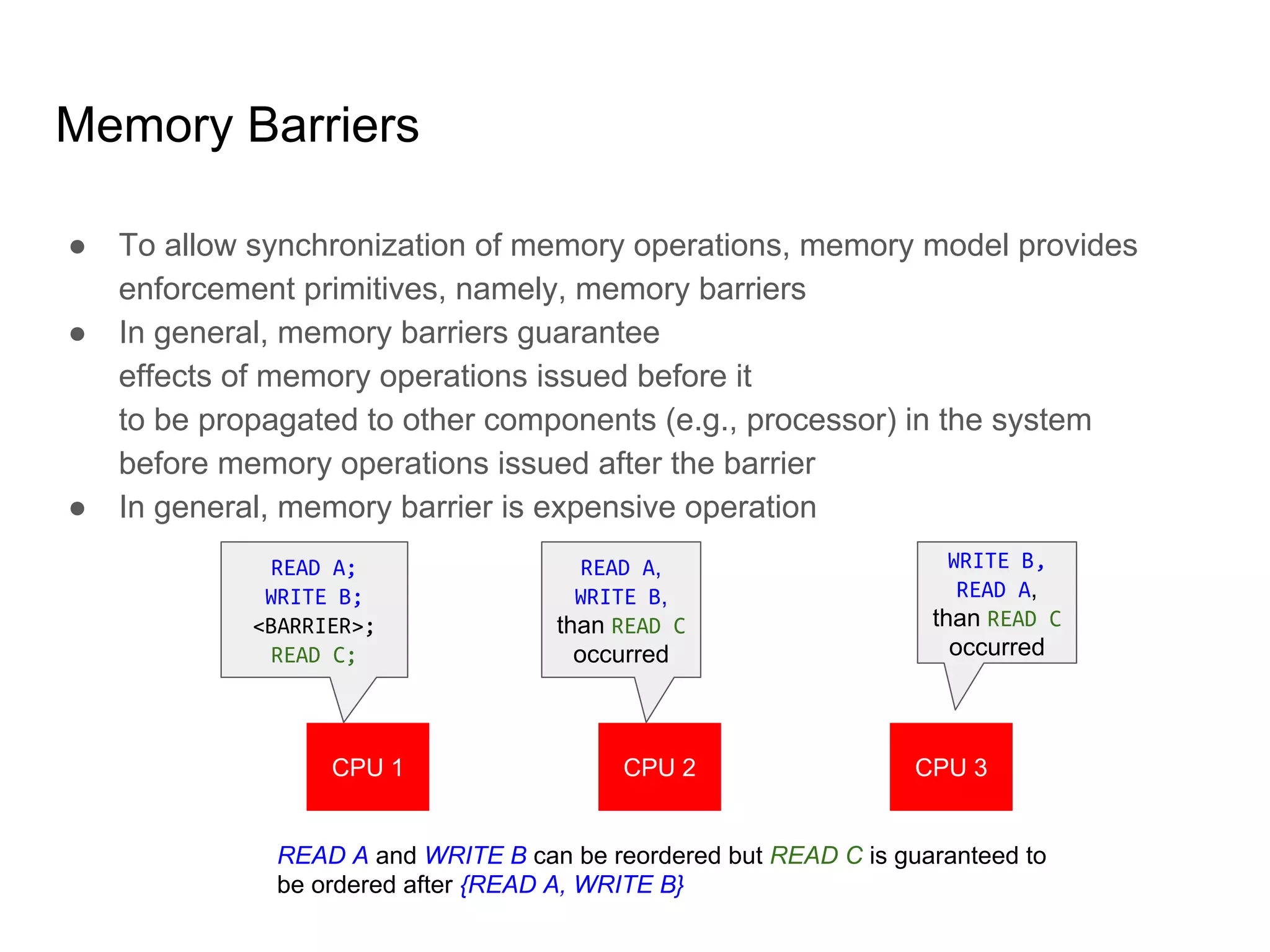

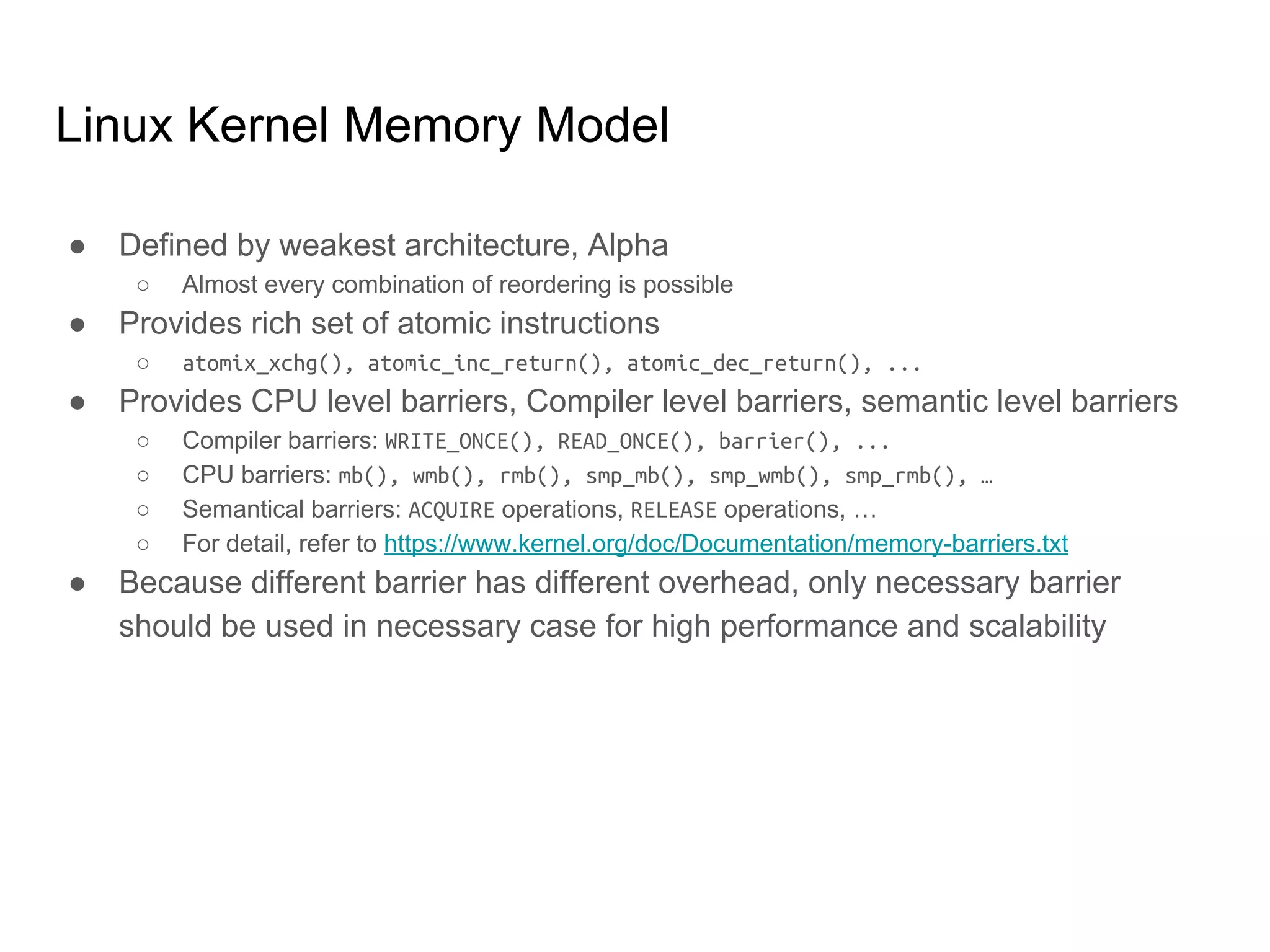

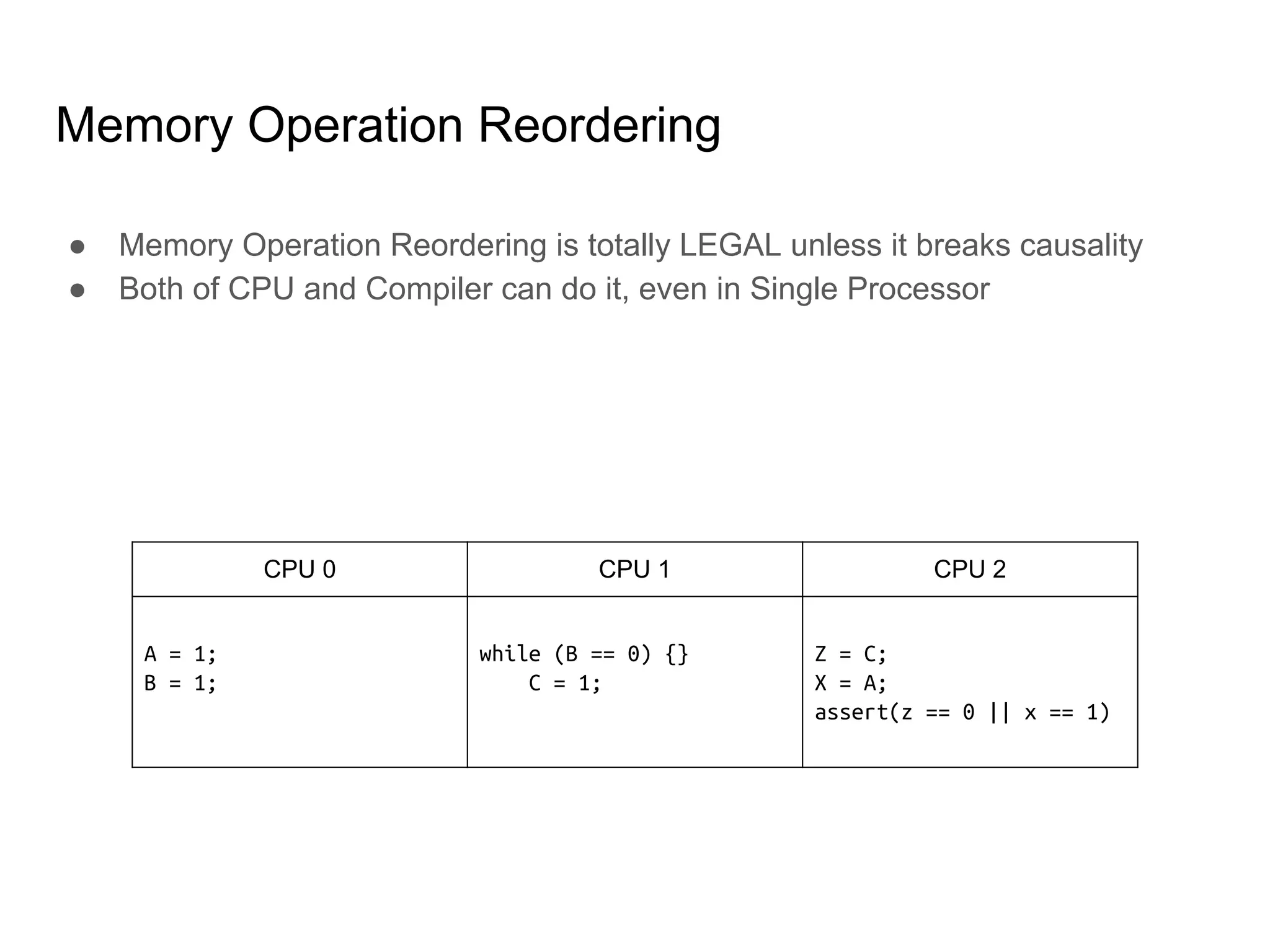

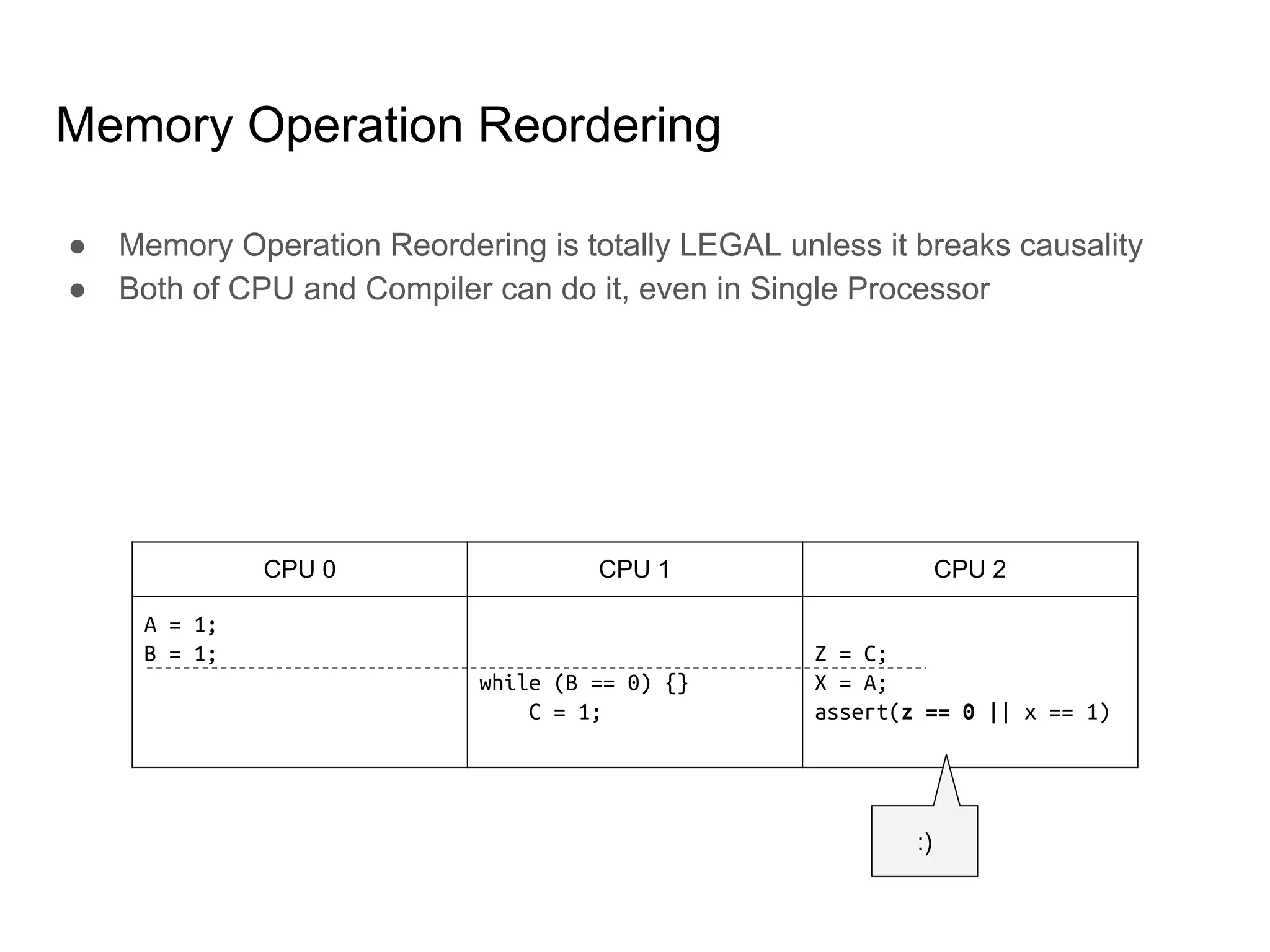

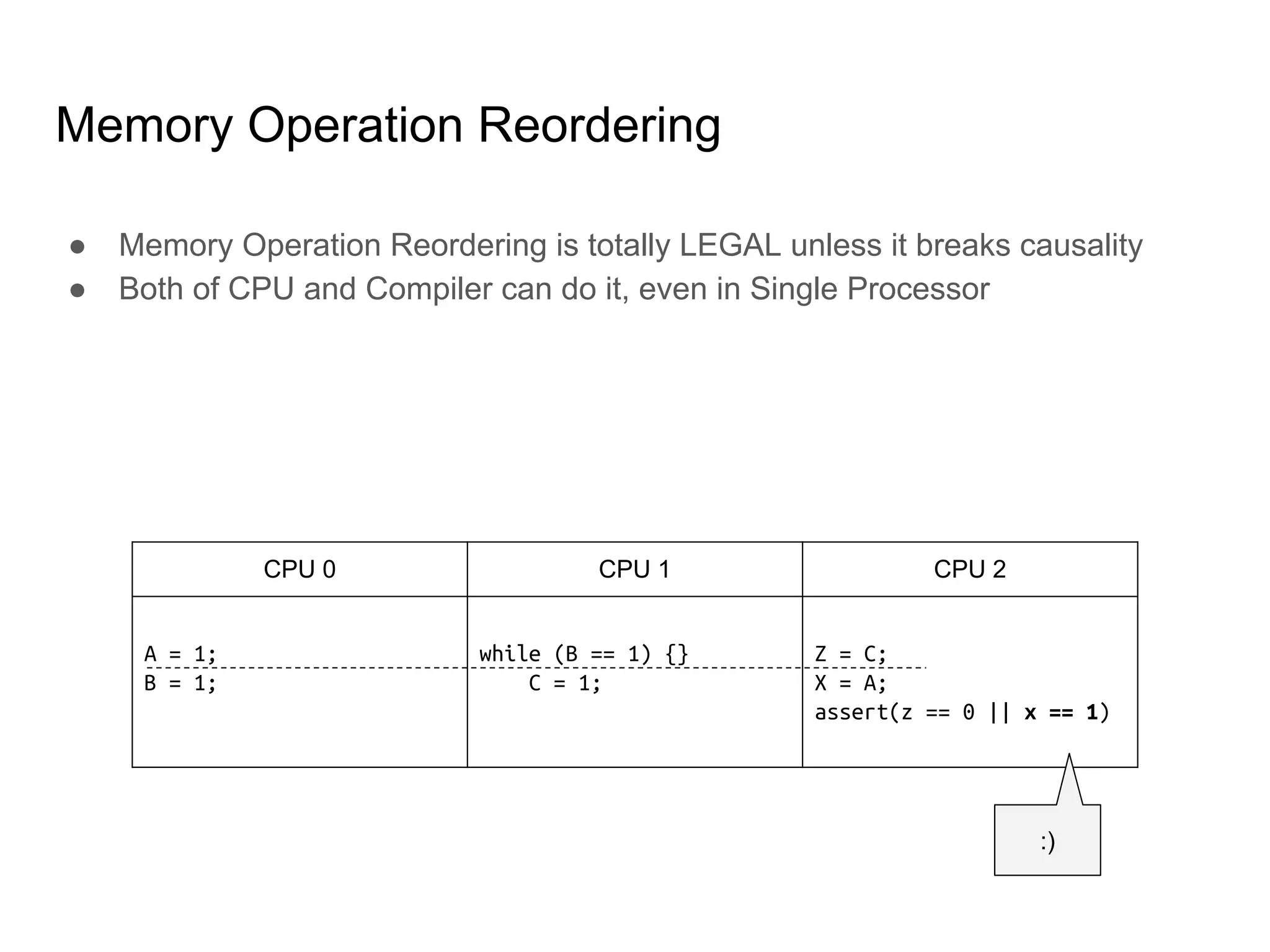

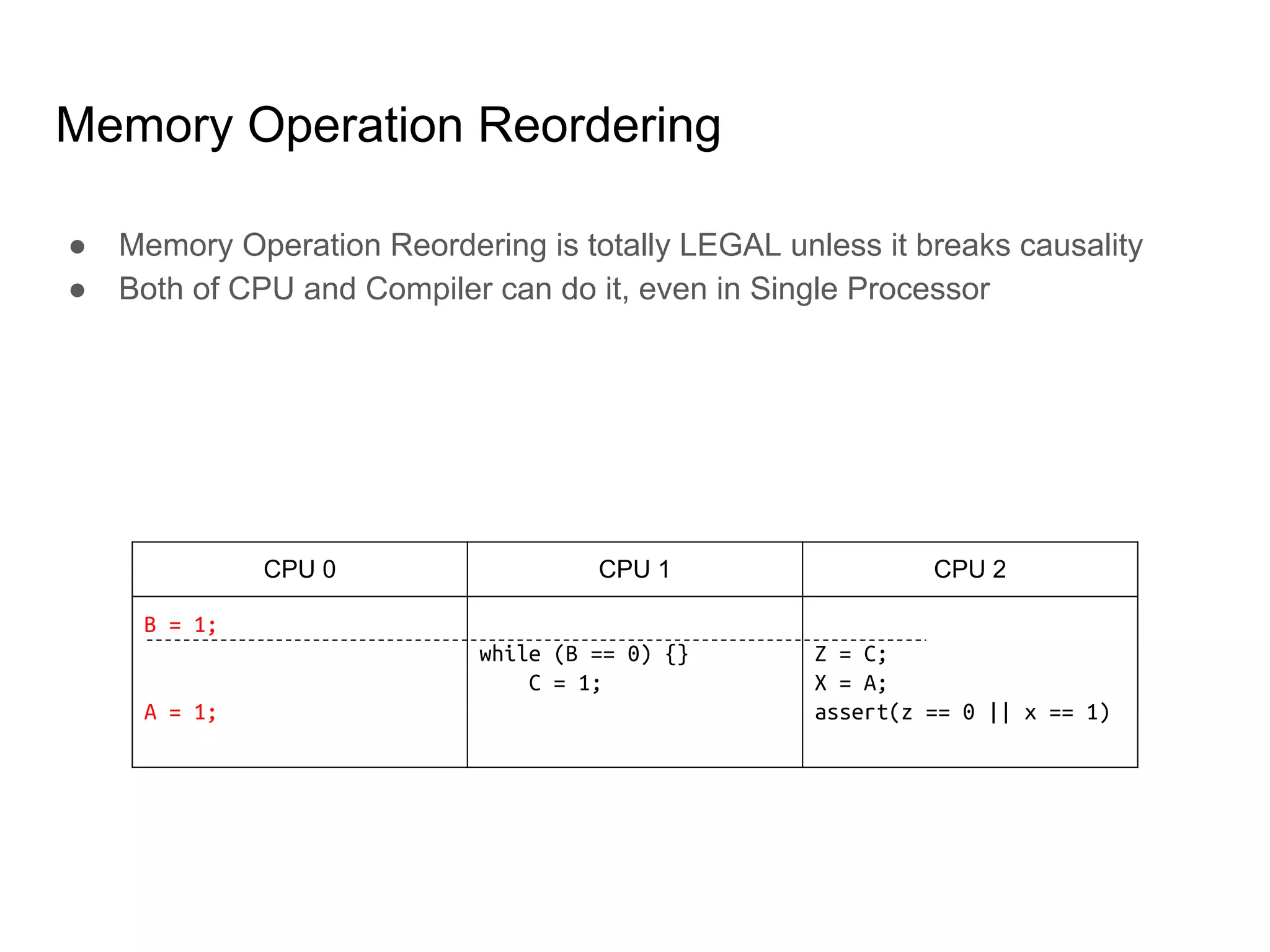

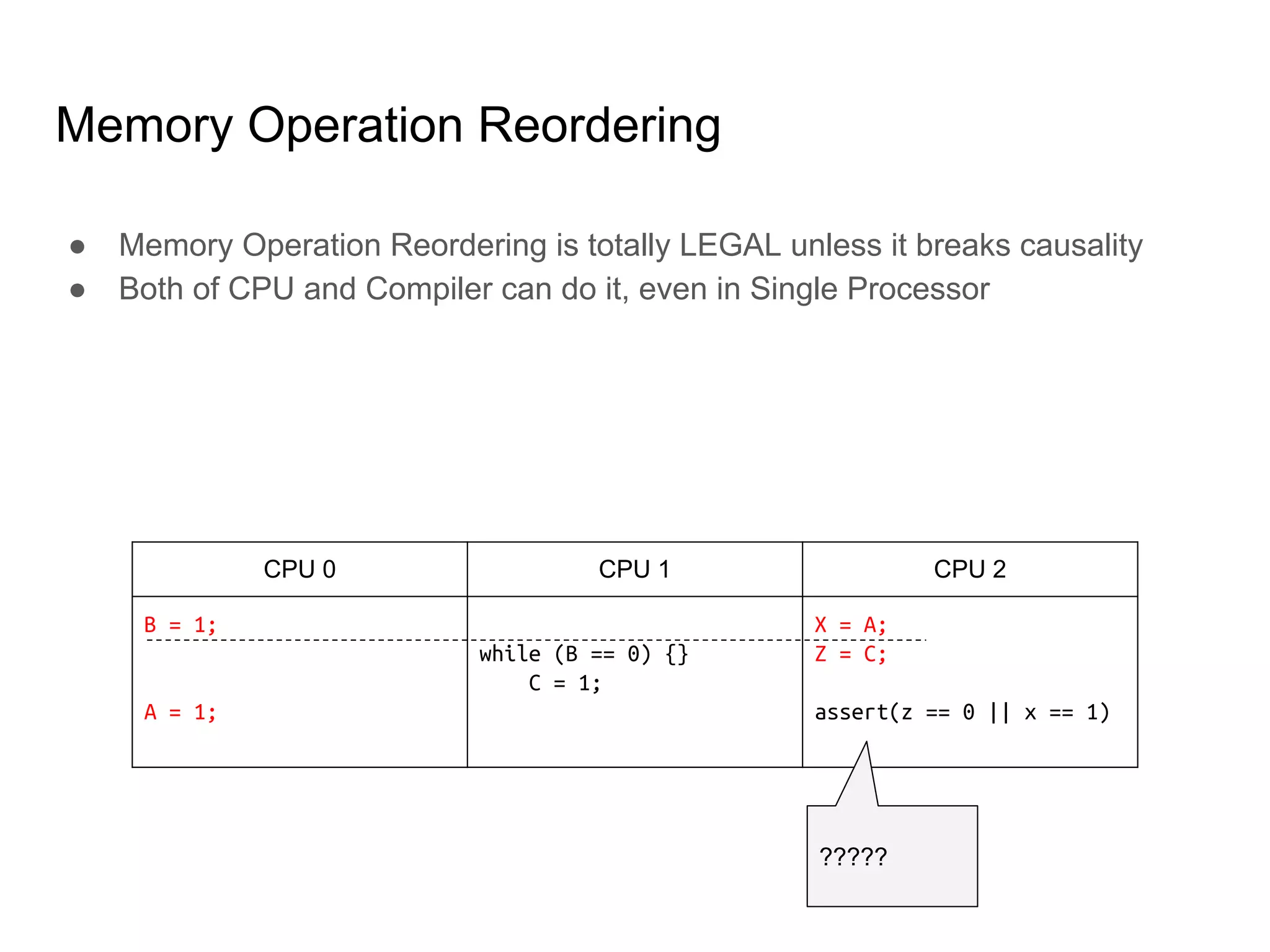

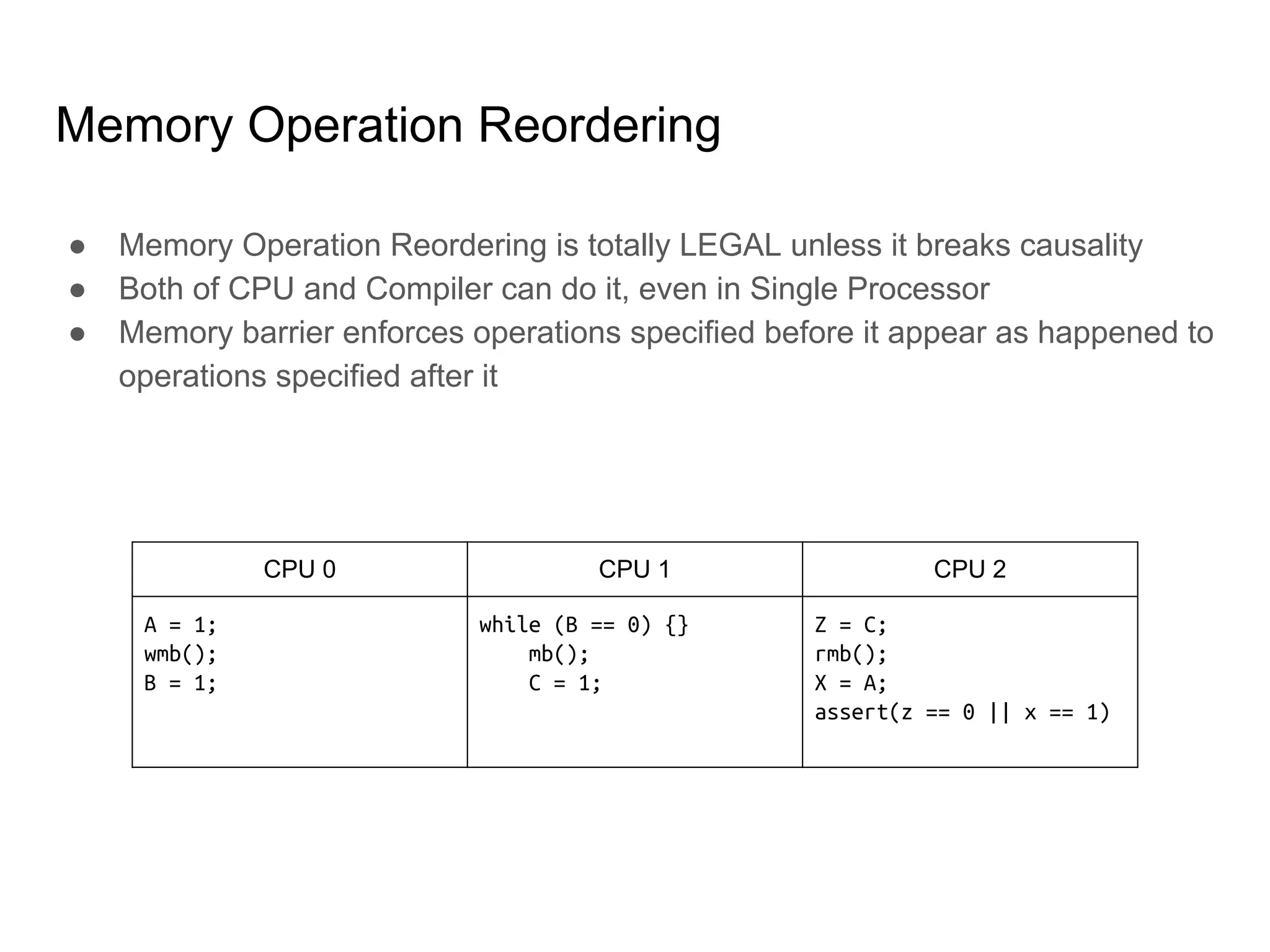

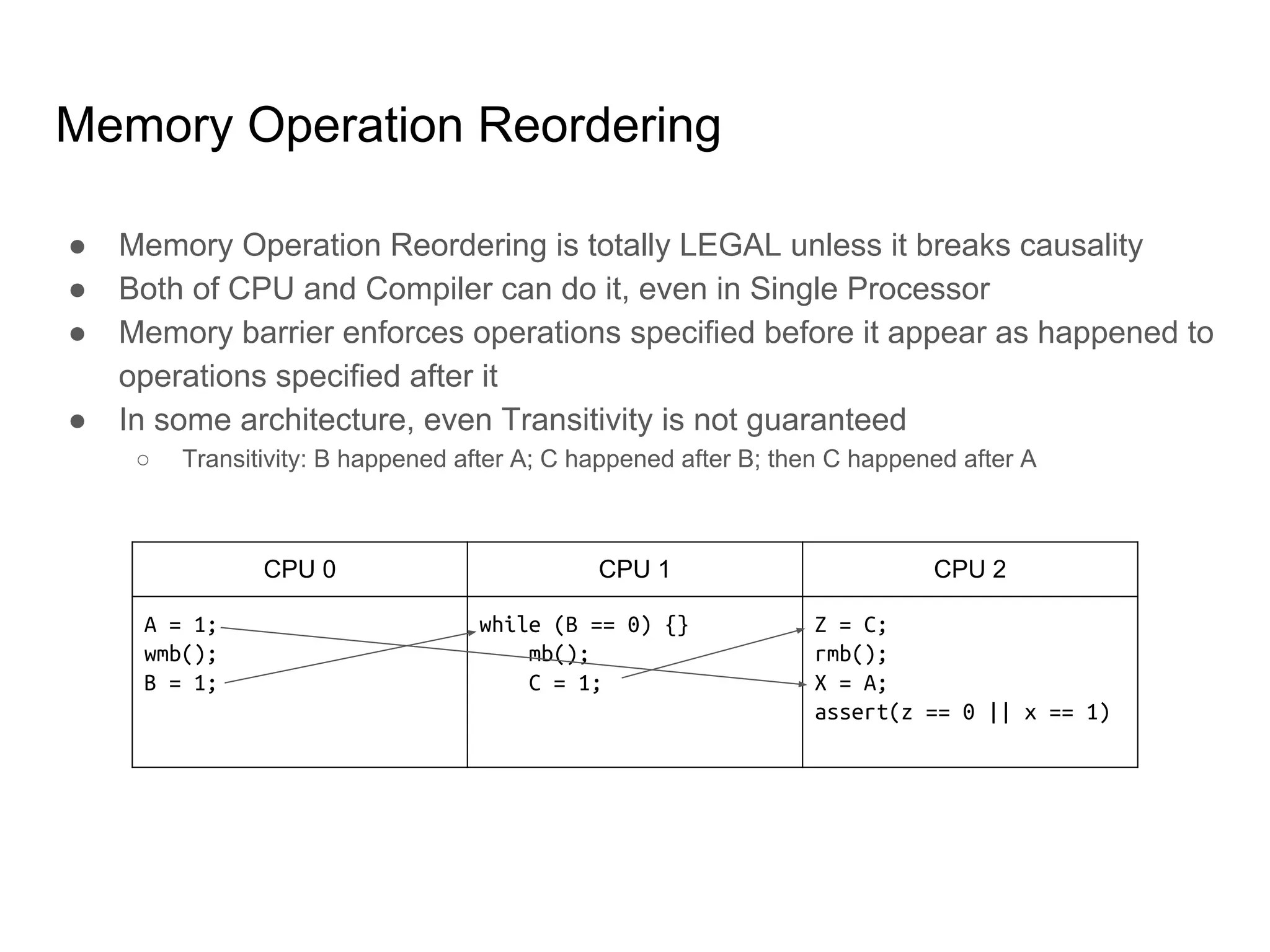

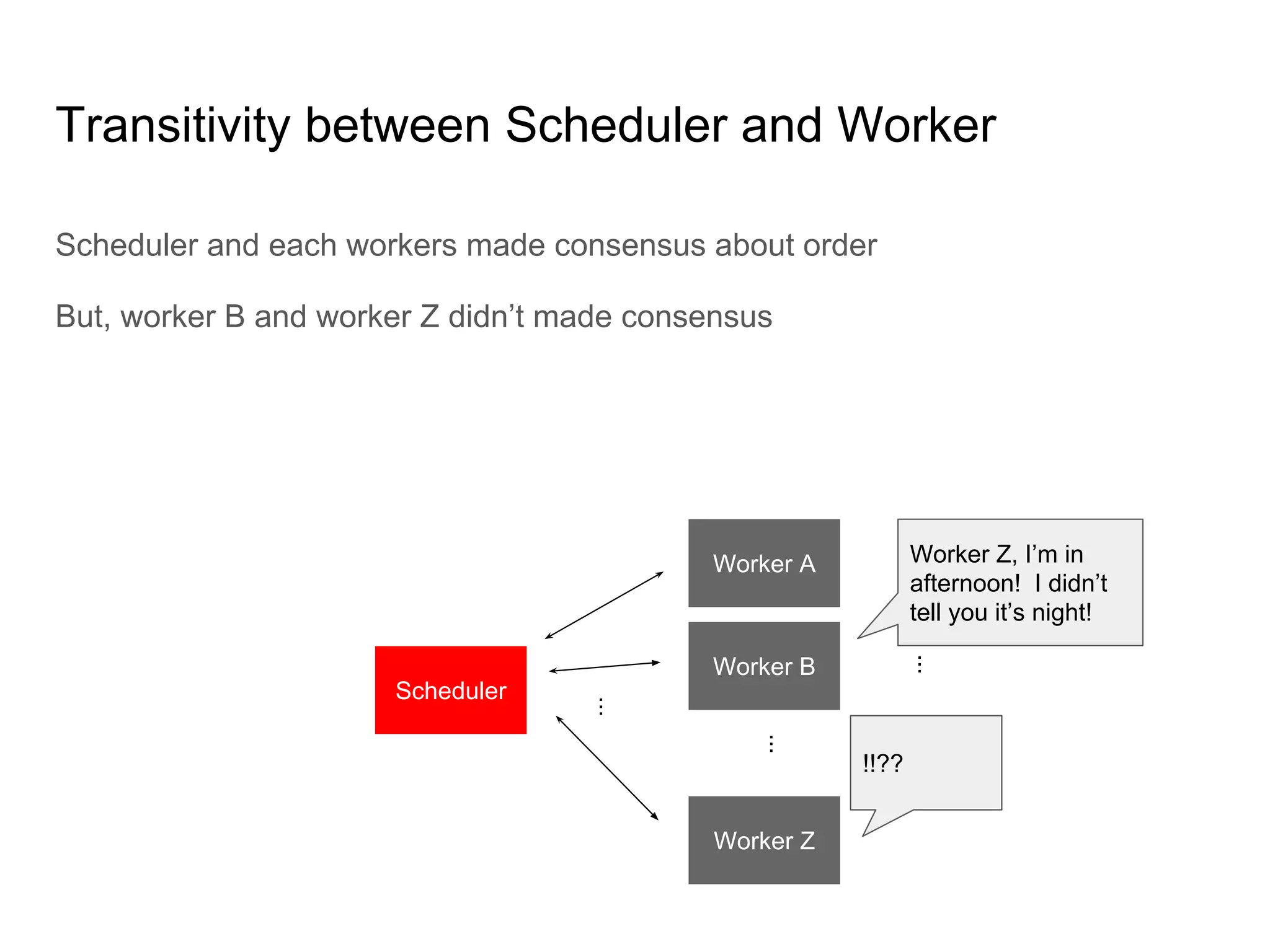

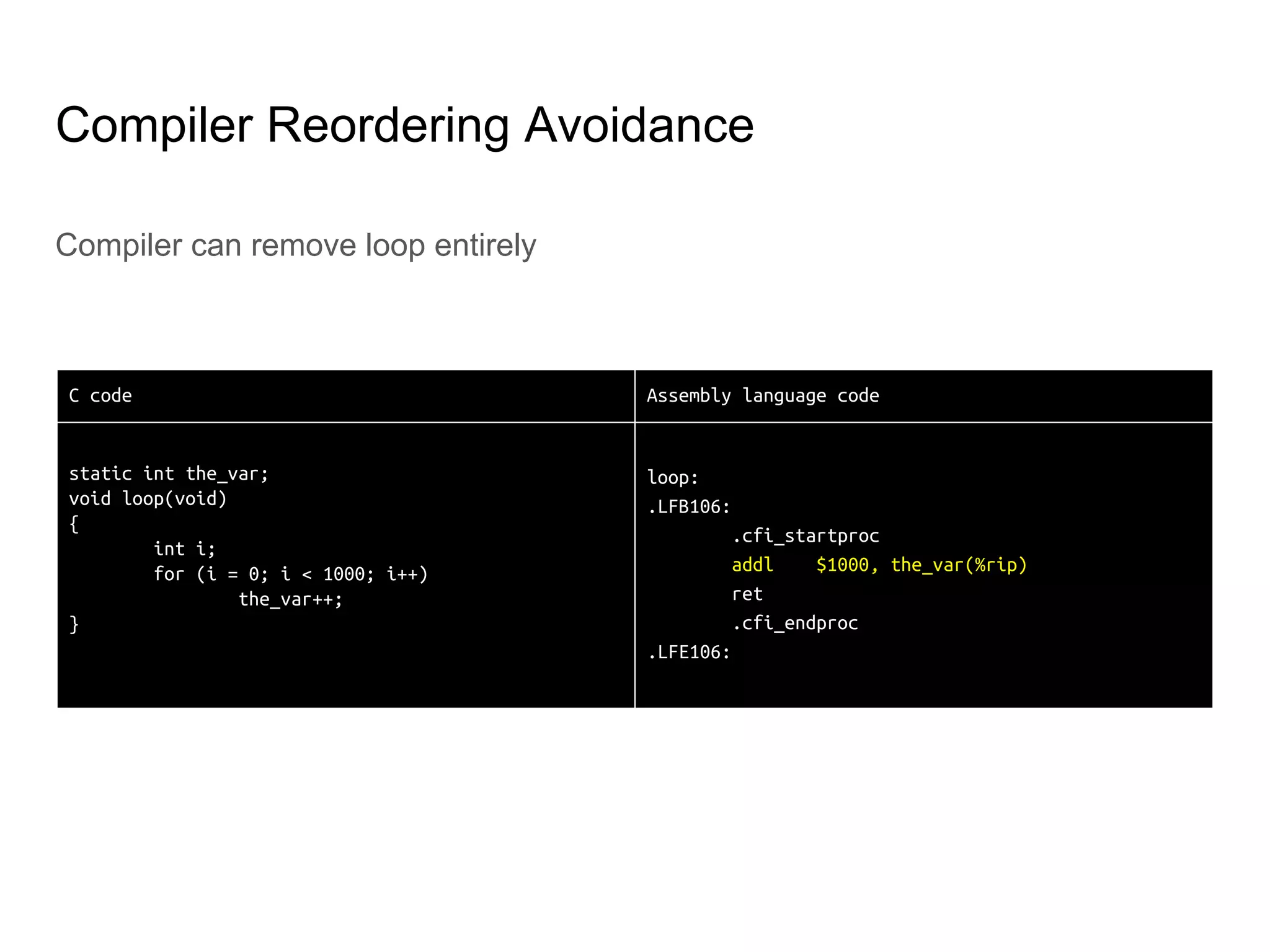

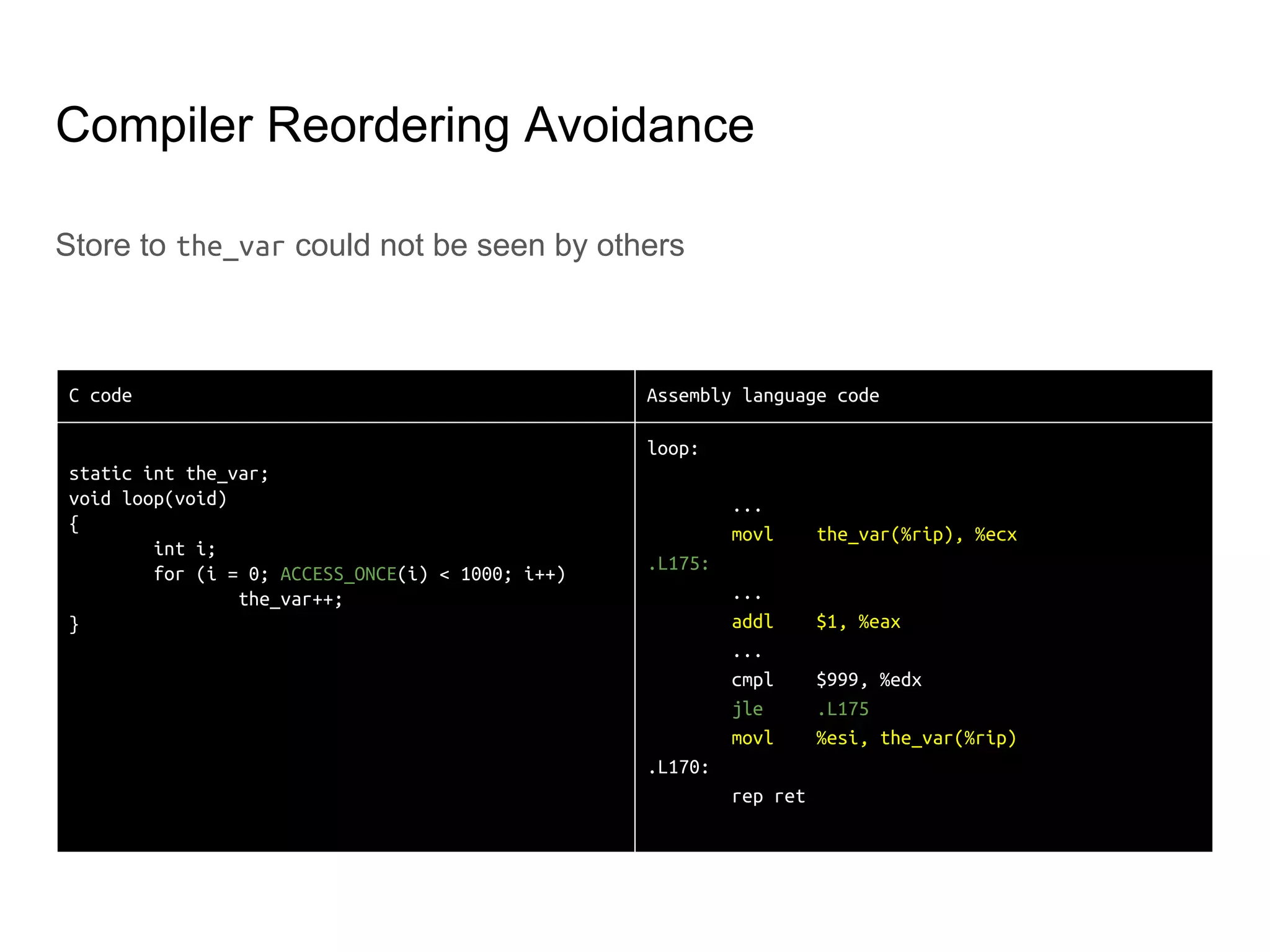

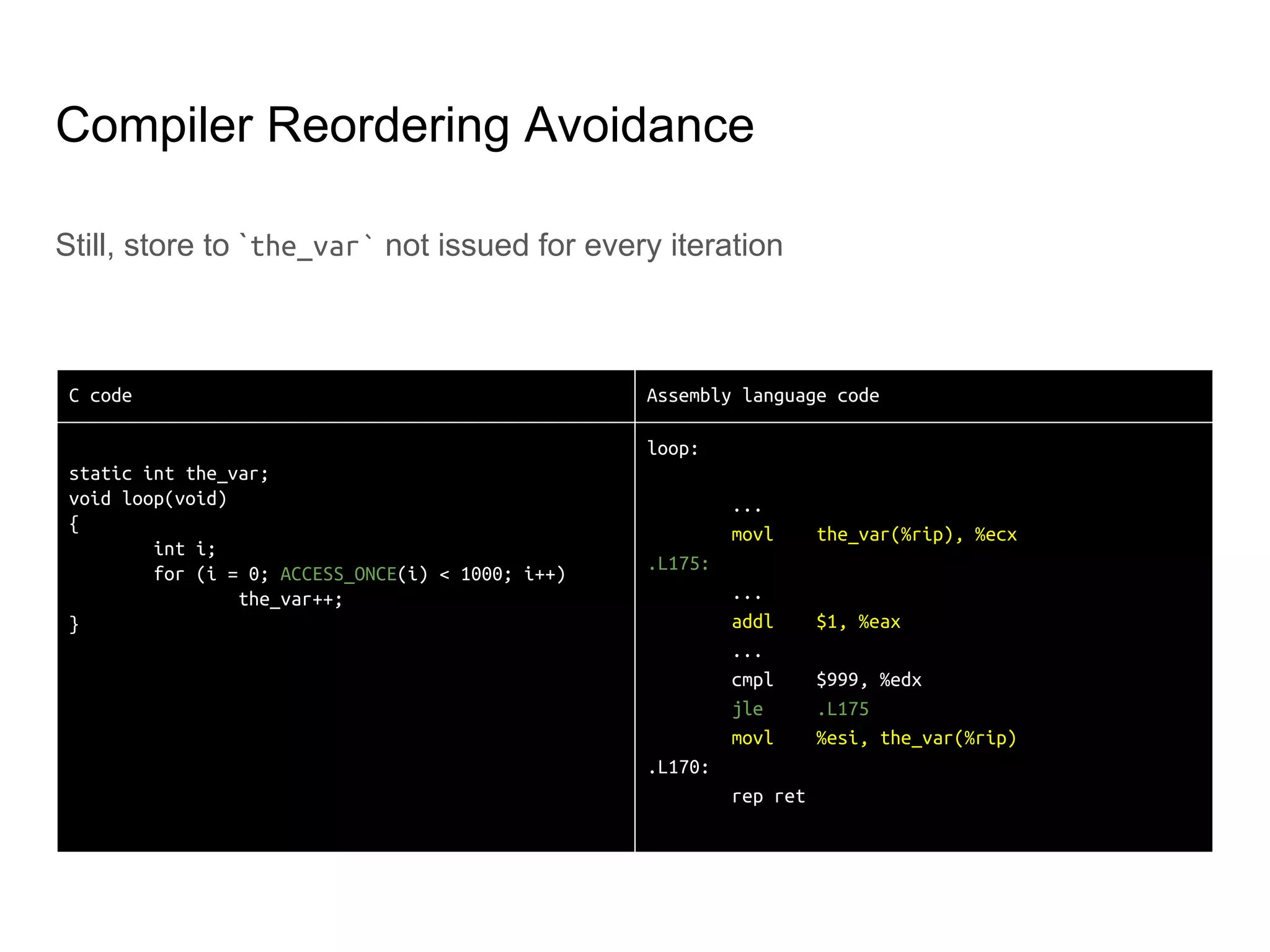

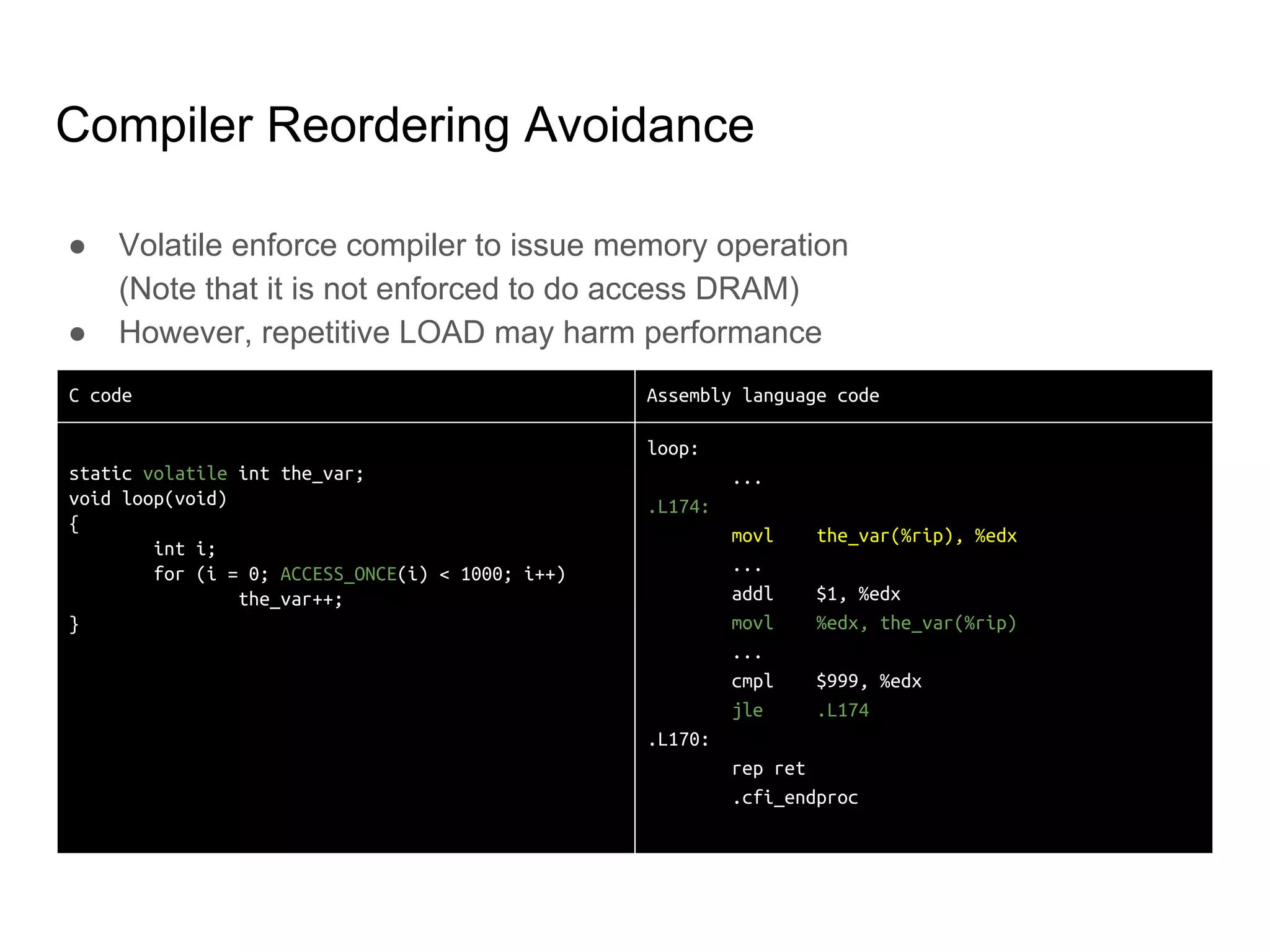

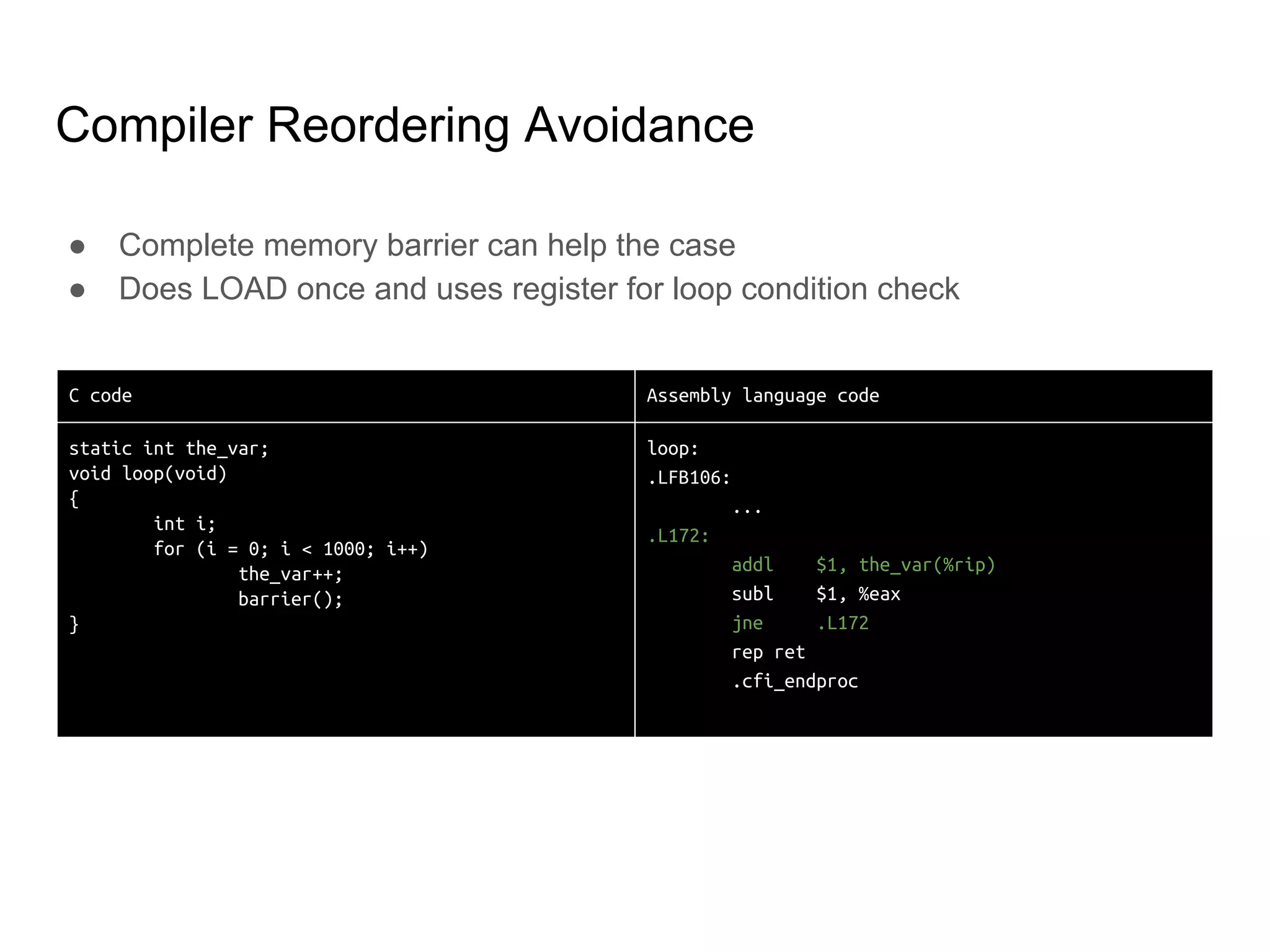

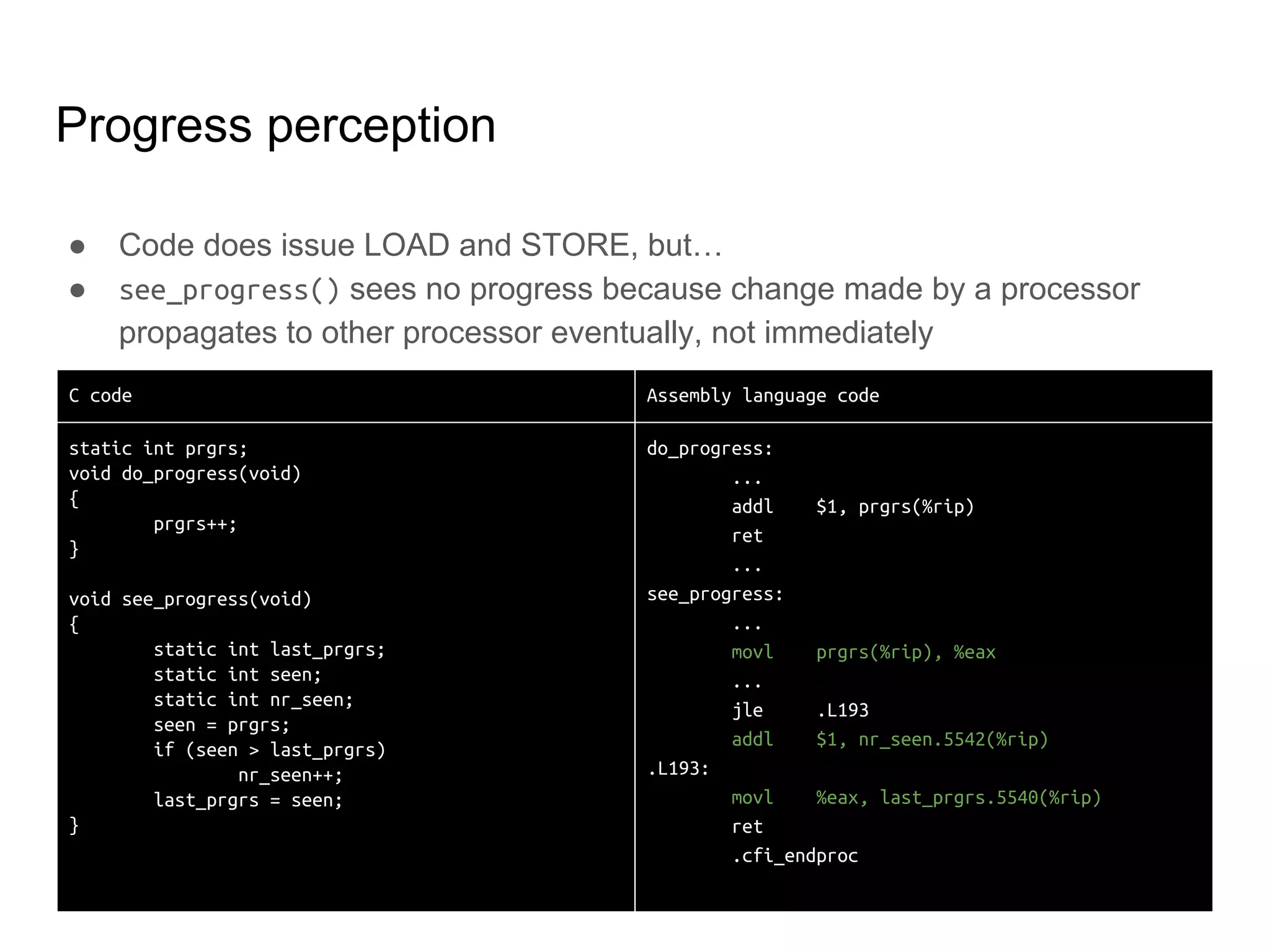

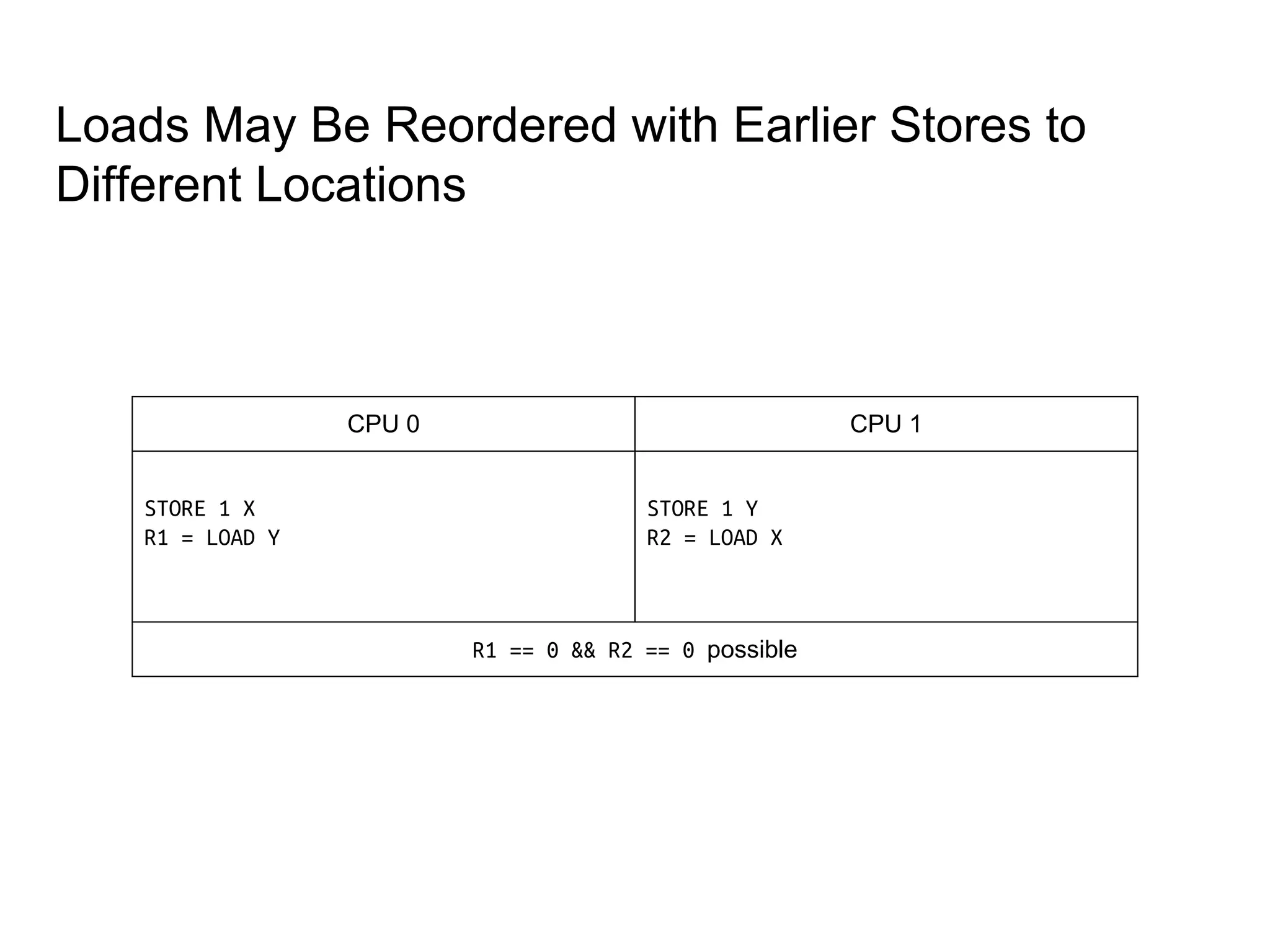

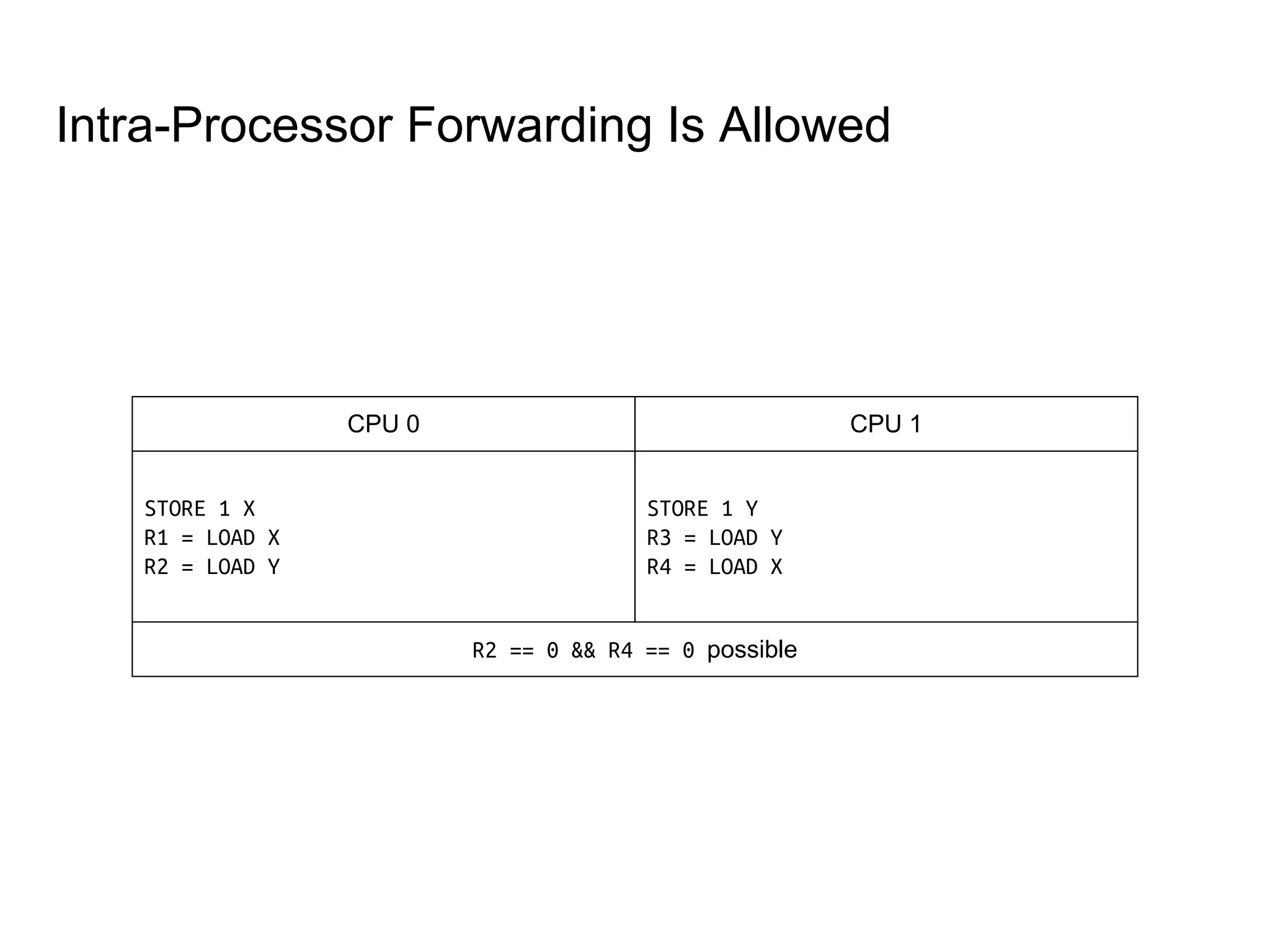

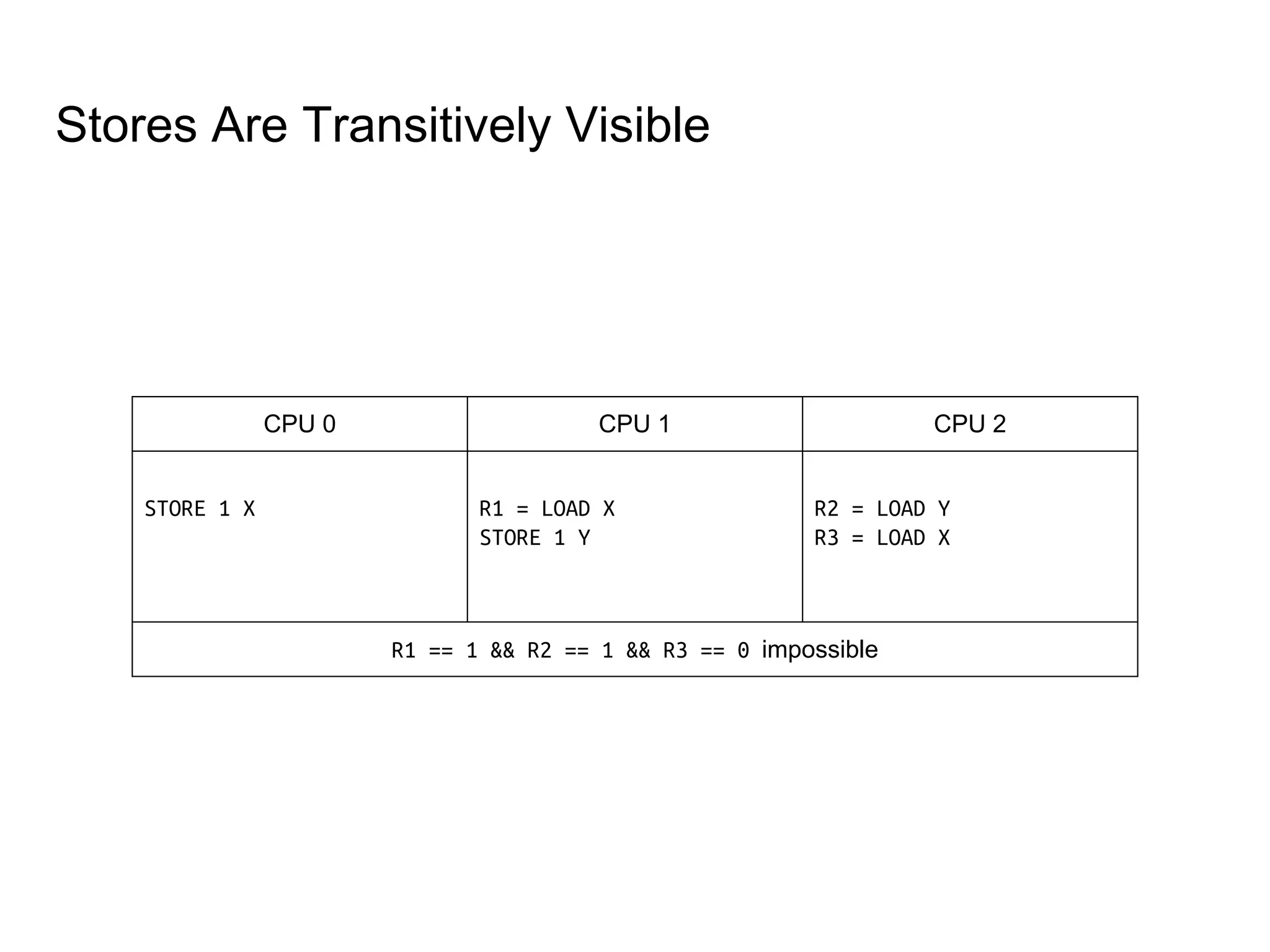

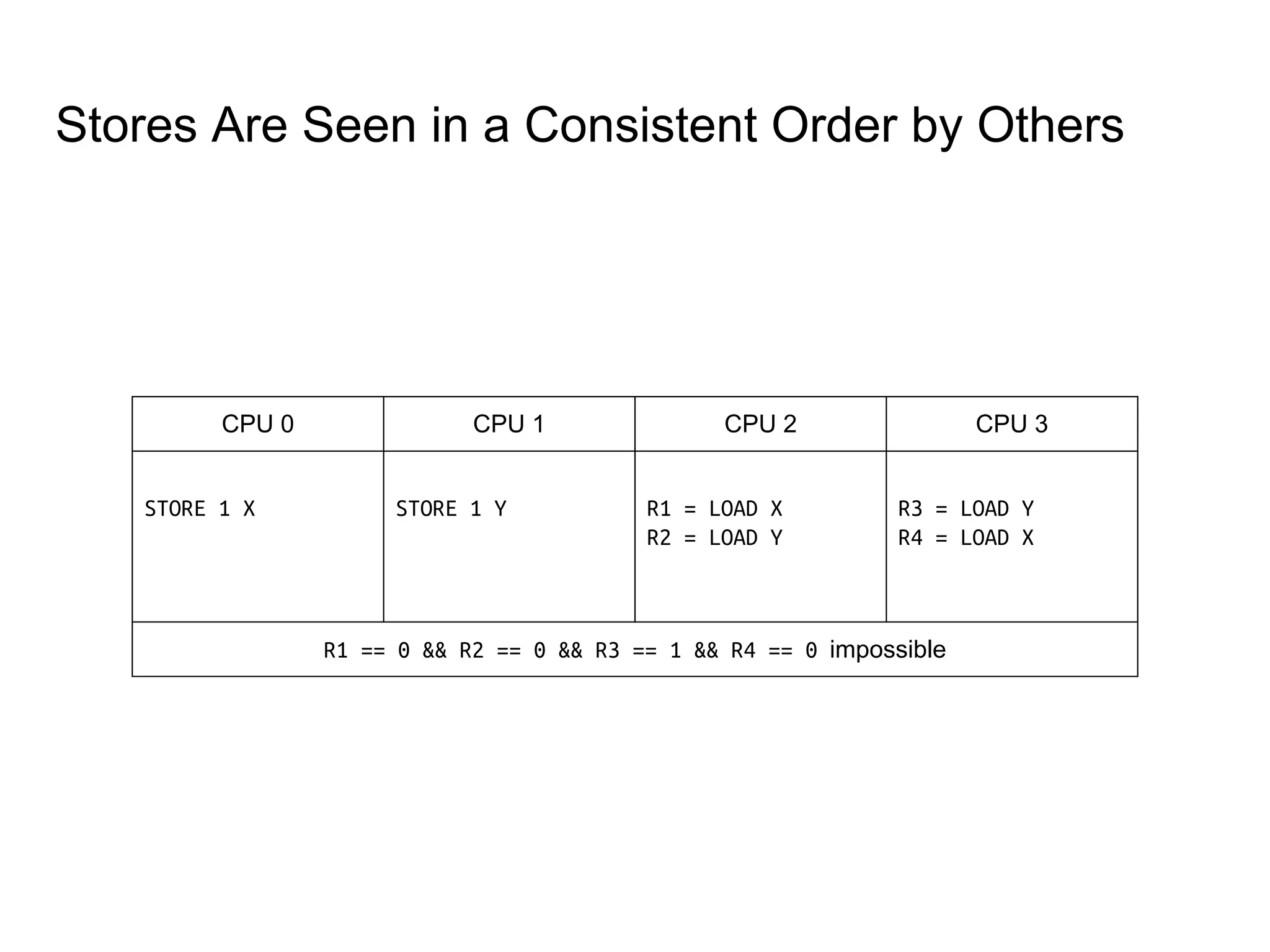

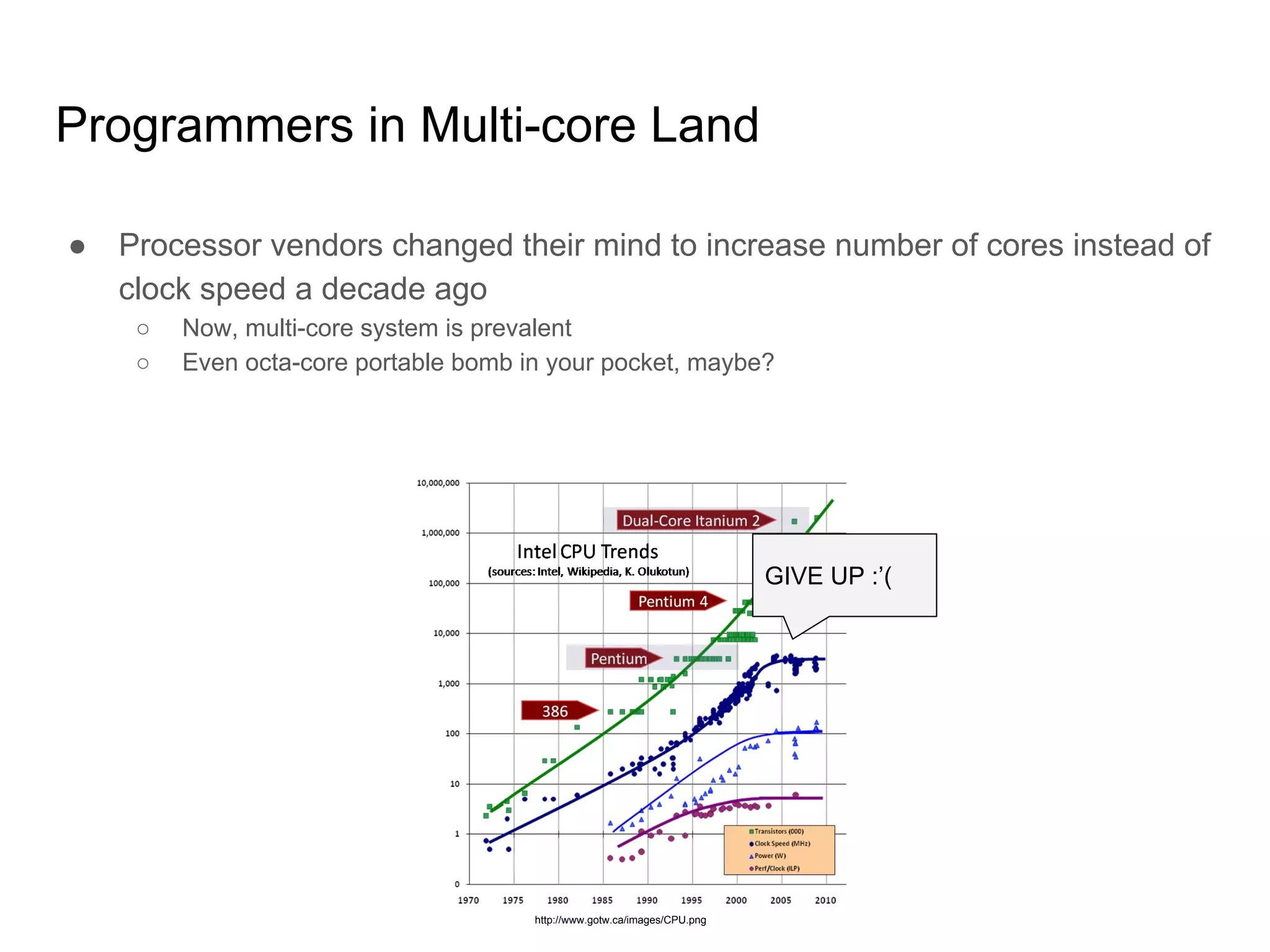

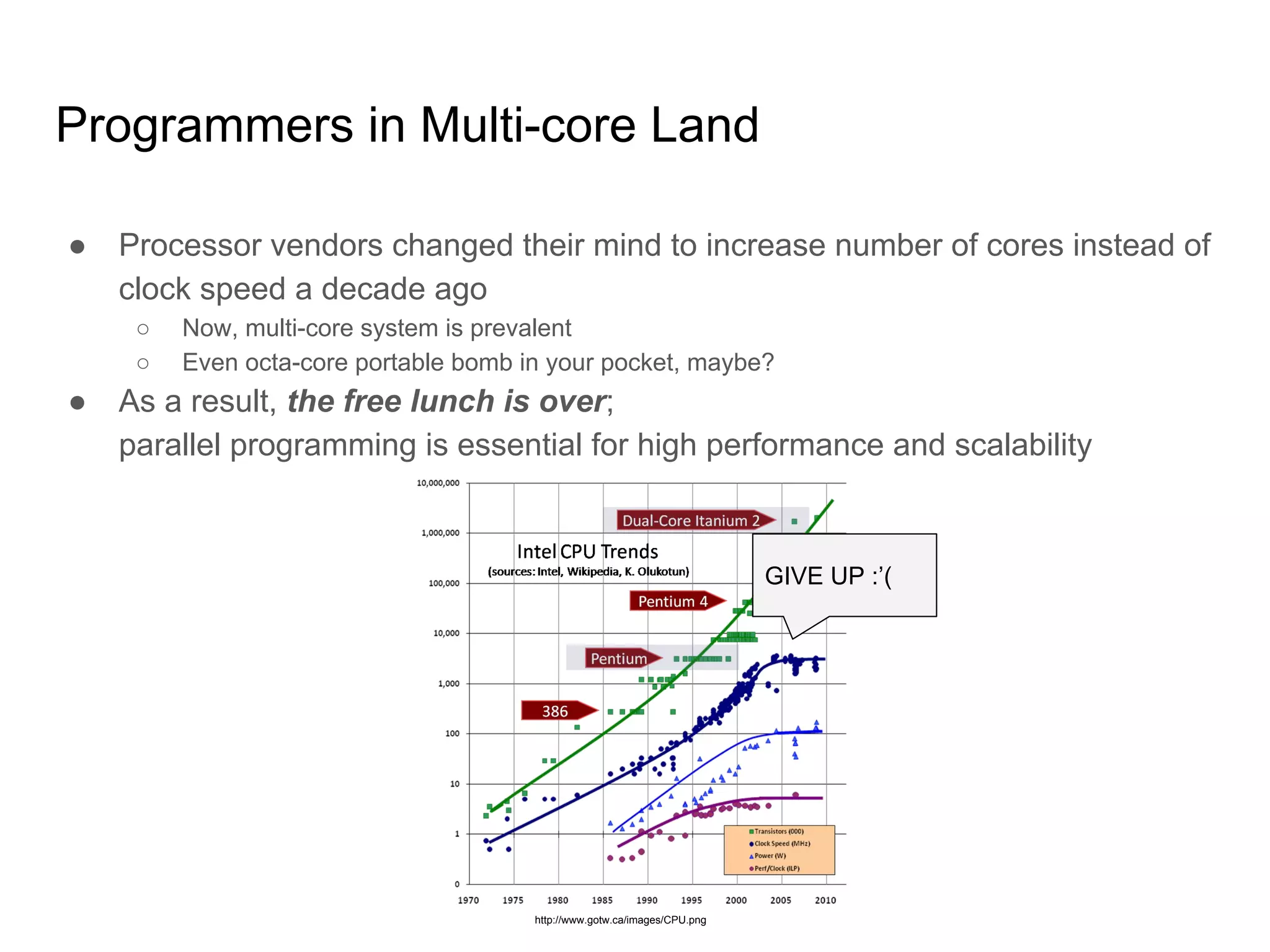

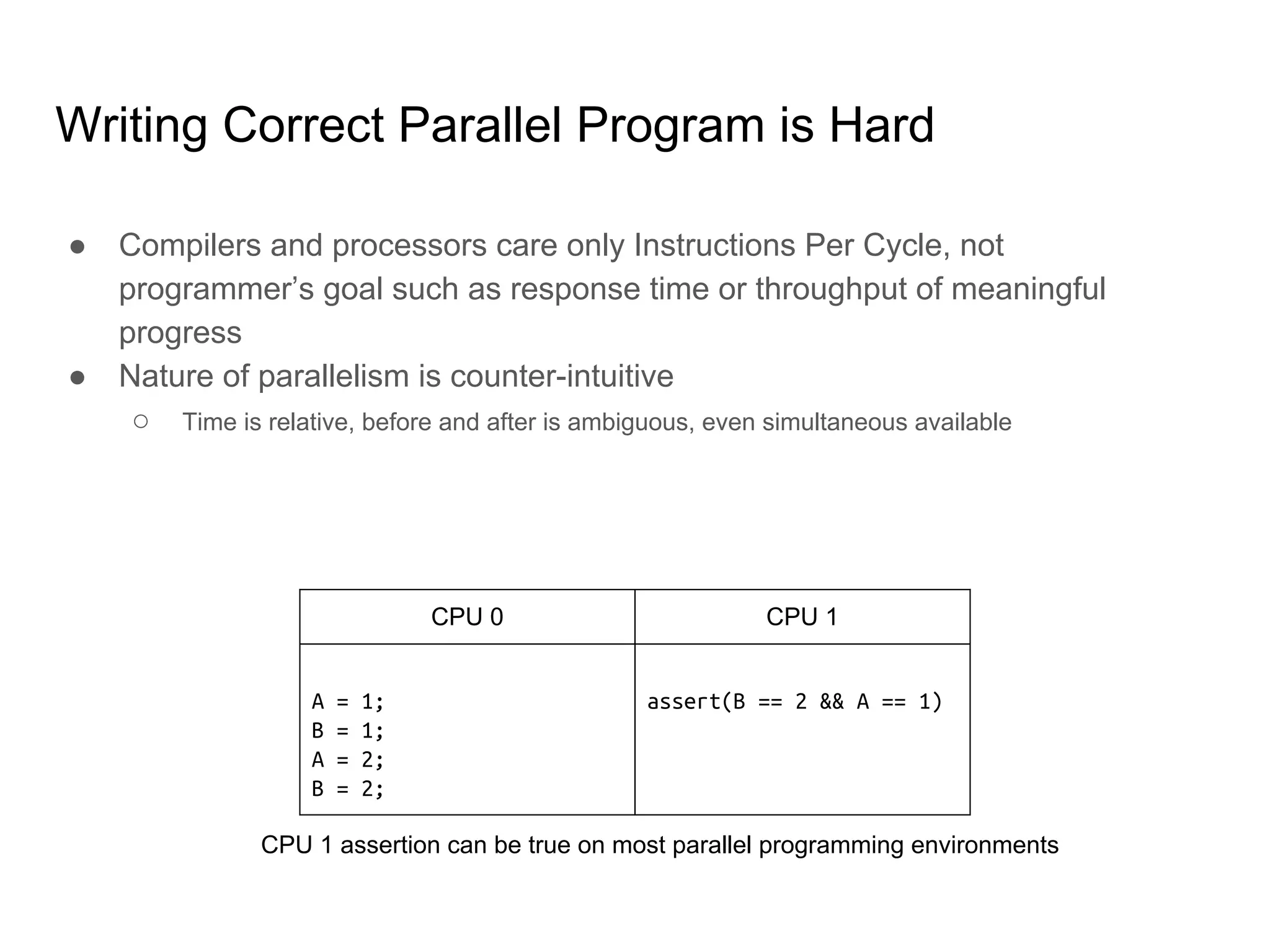

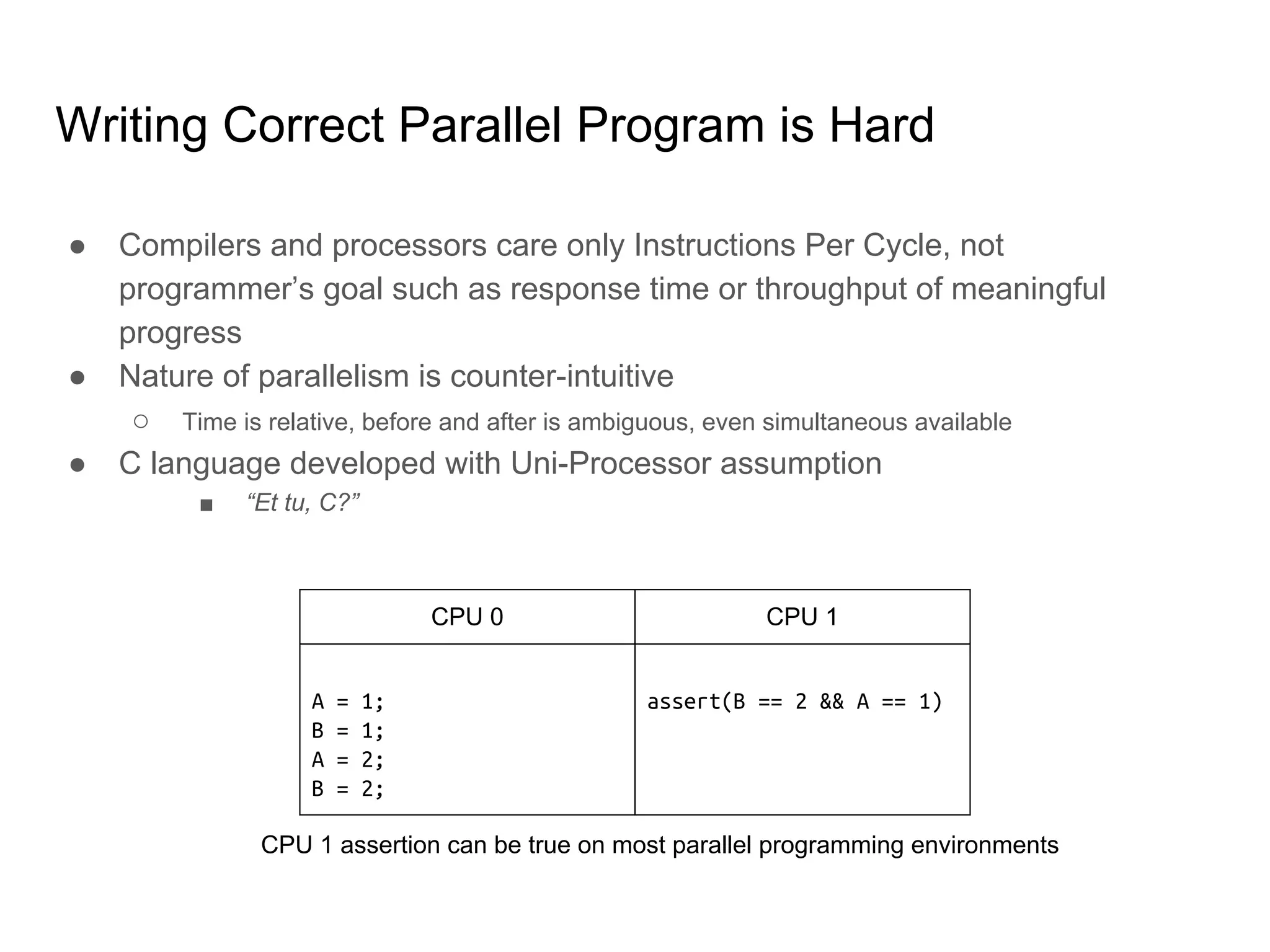

SeongJae Park introduces himself and his work contributing to the Linux kernel memory model documentation. He developed a guaranteed contiguous memory allocator and maintains the Korean translation of the kernel's memory barrier documentation. The document discusses how the increasing prevalence of multi-core processors requires careful programming to ensure correct parallel execution given relaxed memory ordering. It notes that compilers and CPUs optimize for instruction throughput over programmer goals, and memory accesses can be reordered in ways that affect correctness on multi-processors. Understanding the memory model is important for writing high-performance parallel code.

![Reordering for Better IPC[*]

[*]

IPC: Instructions Per Cycle](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingoflinuxkernelmemorymodel-161018063424/75/Understanding-of-linux-kernel-memory-model-9-2048.jpg)