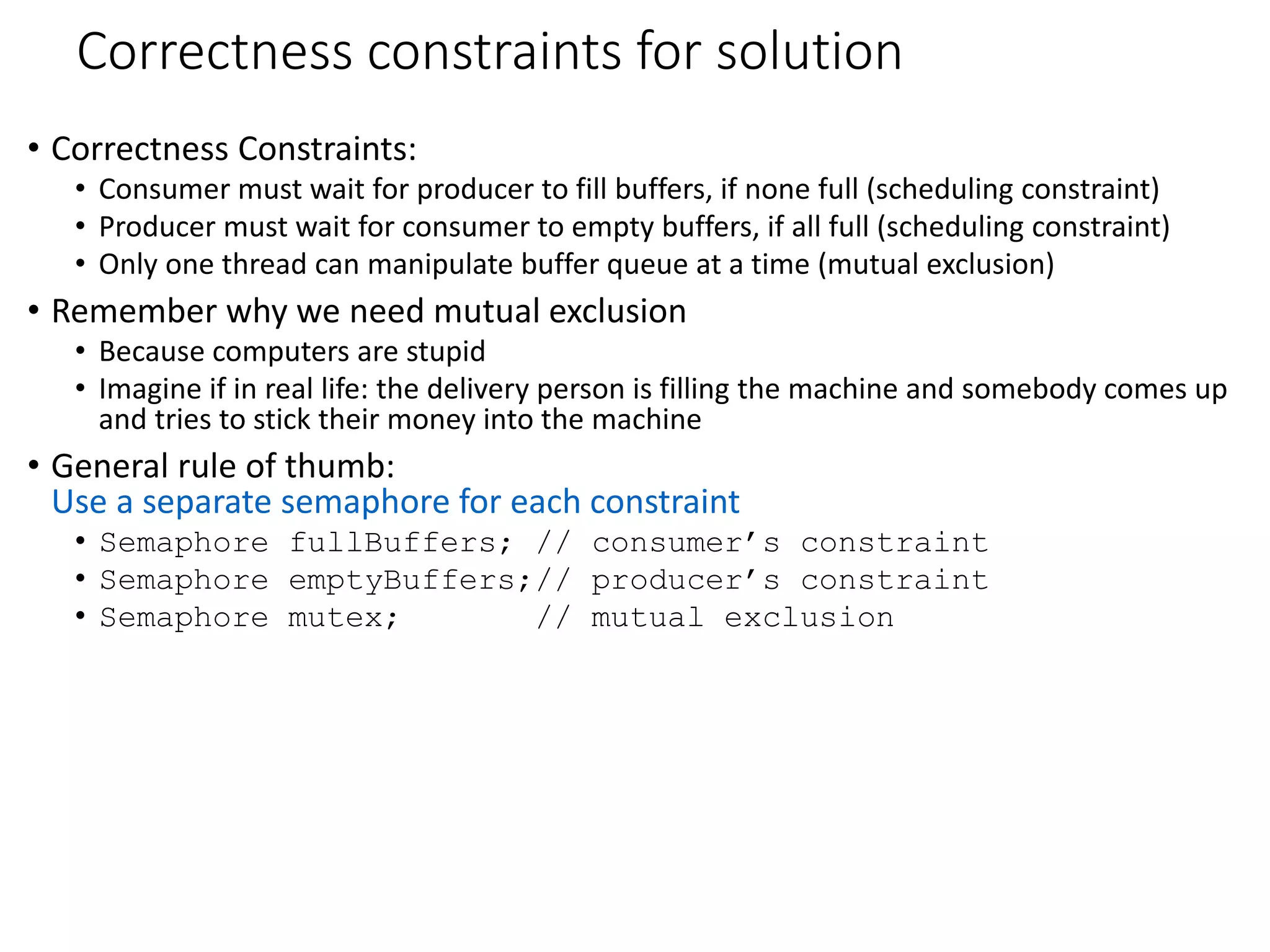

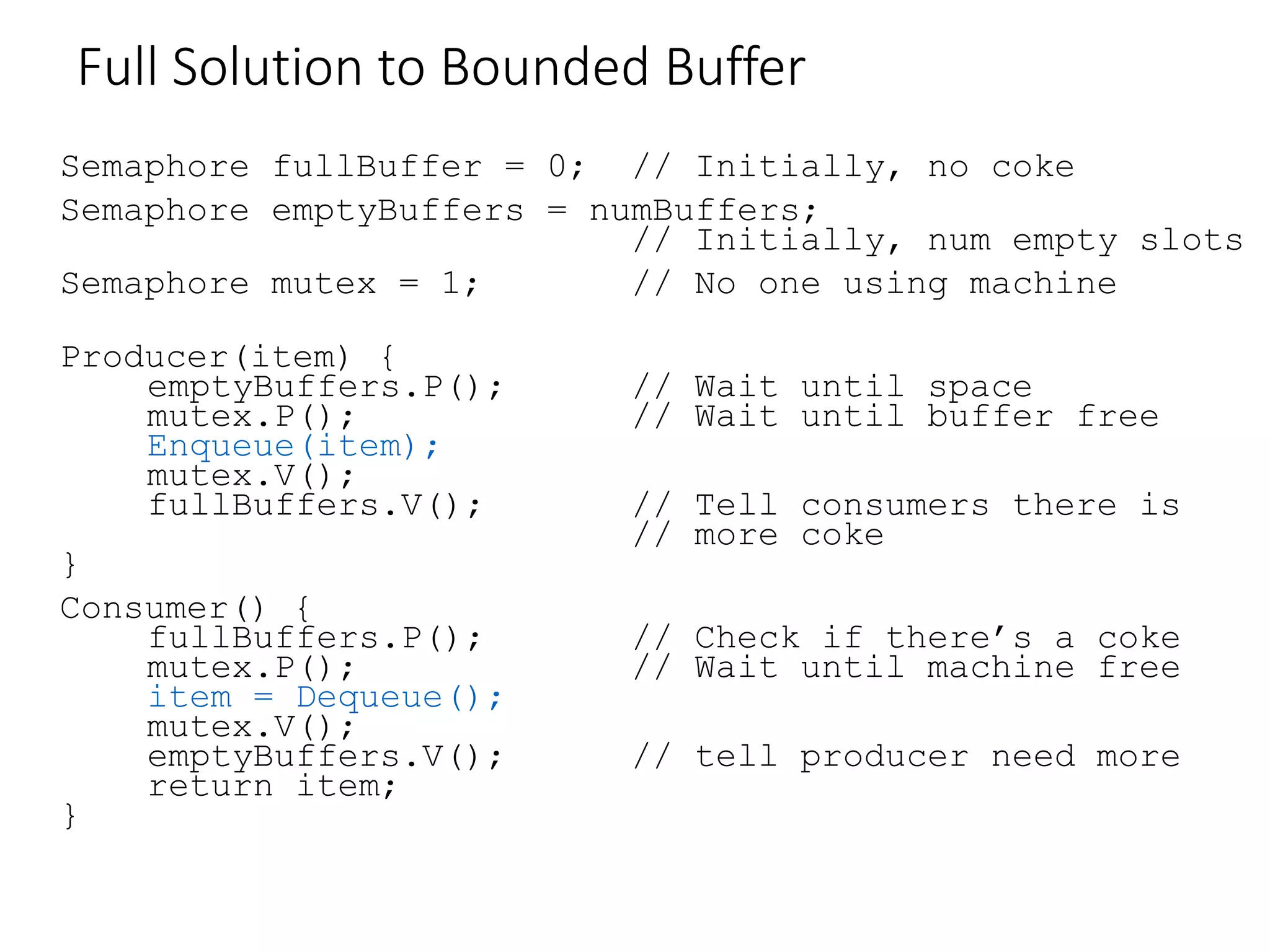

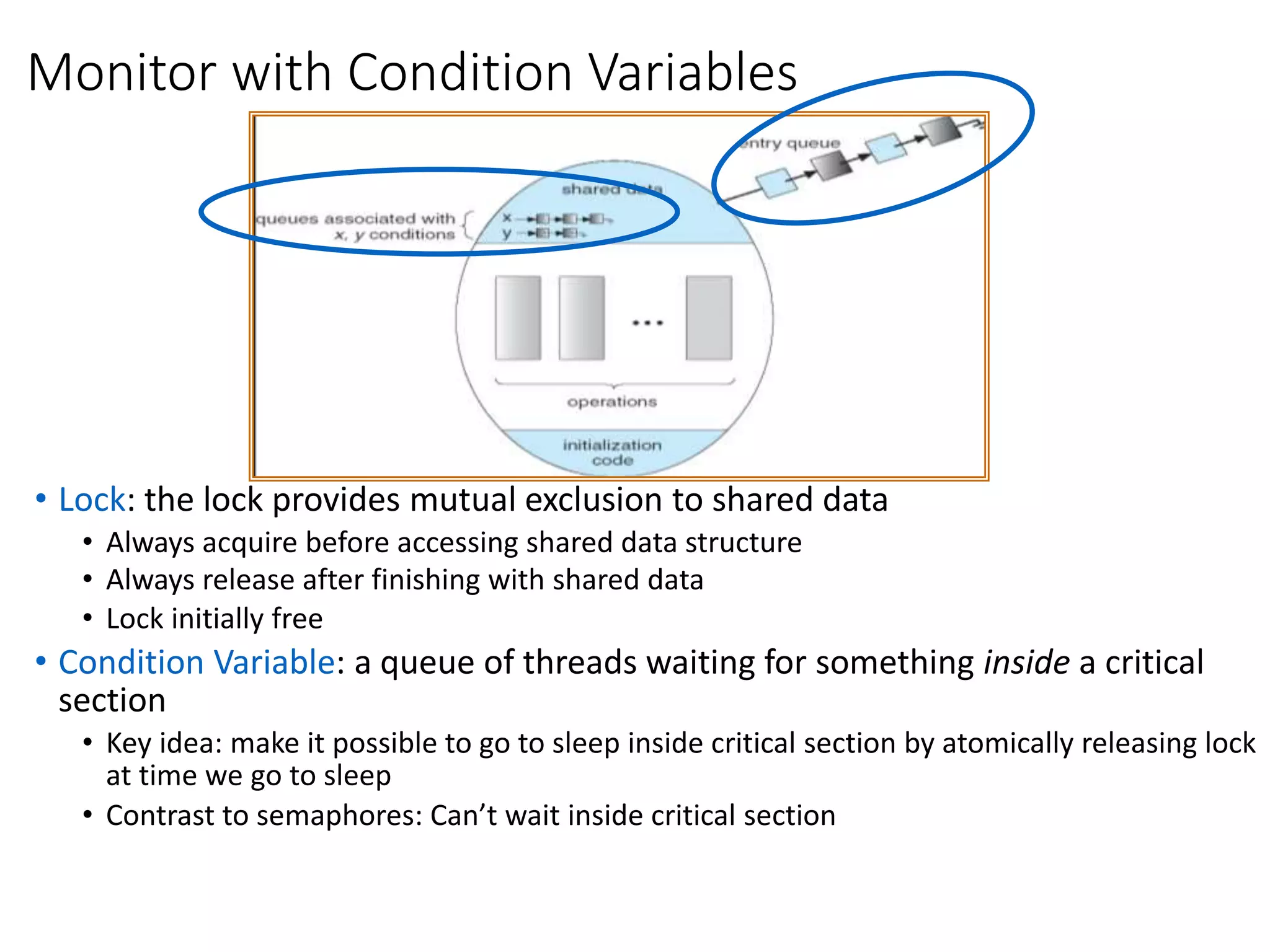

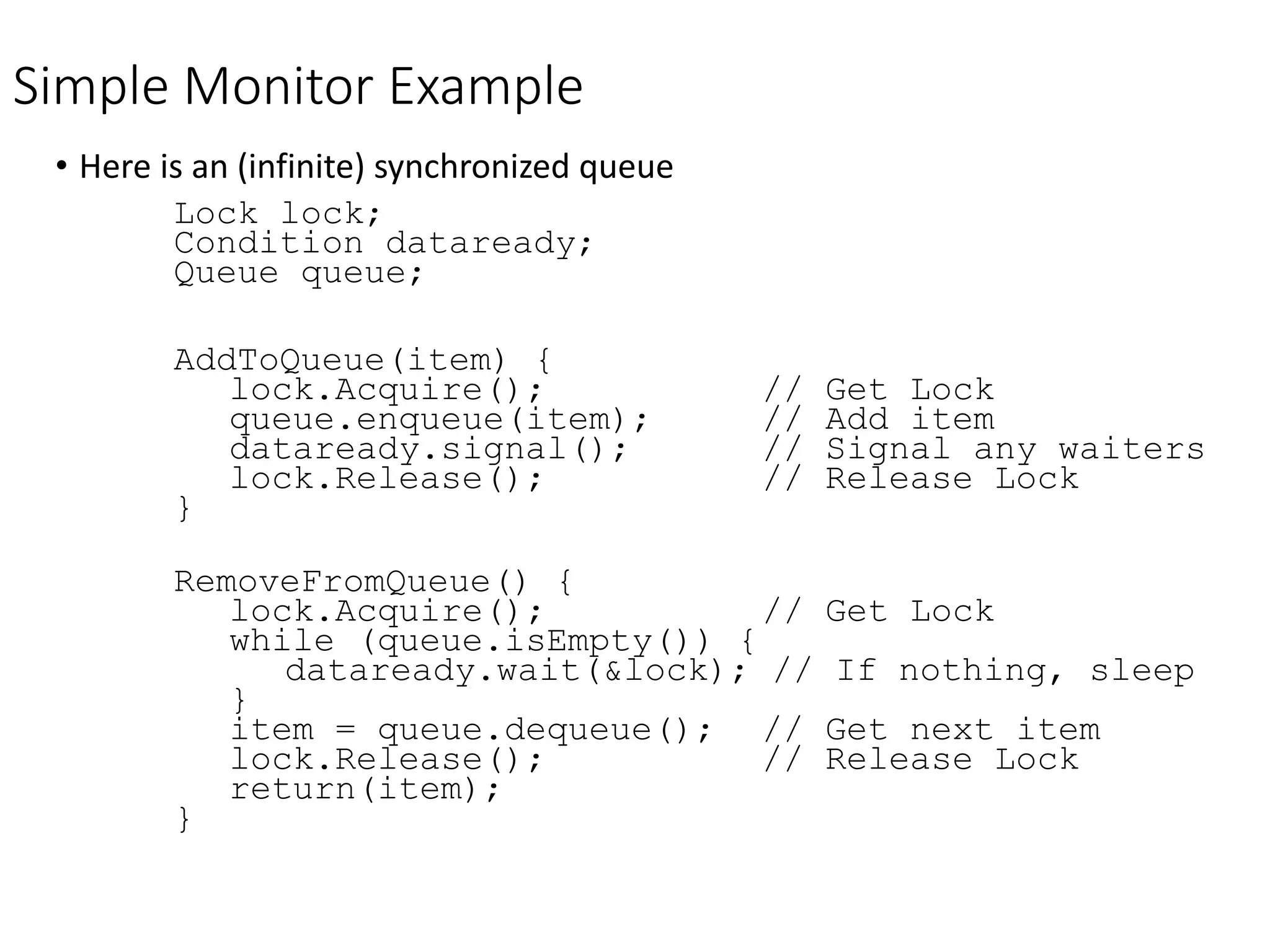

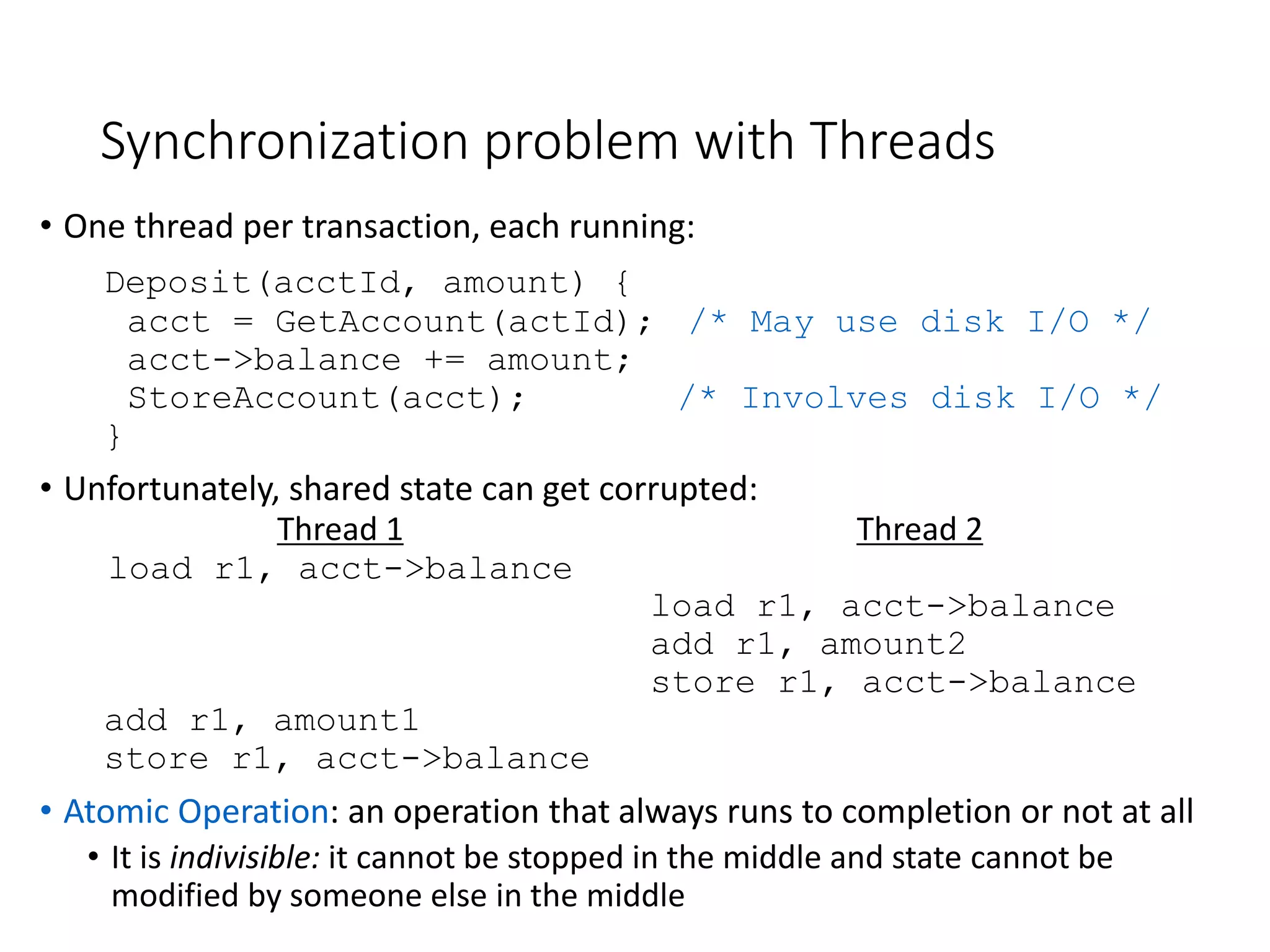

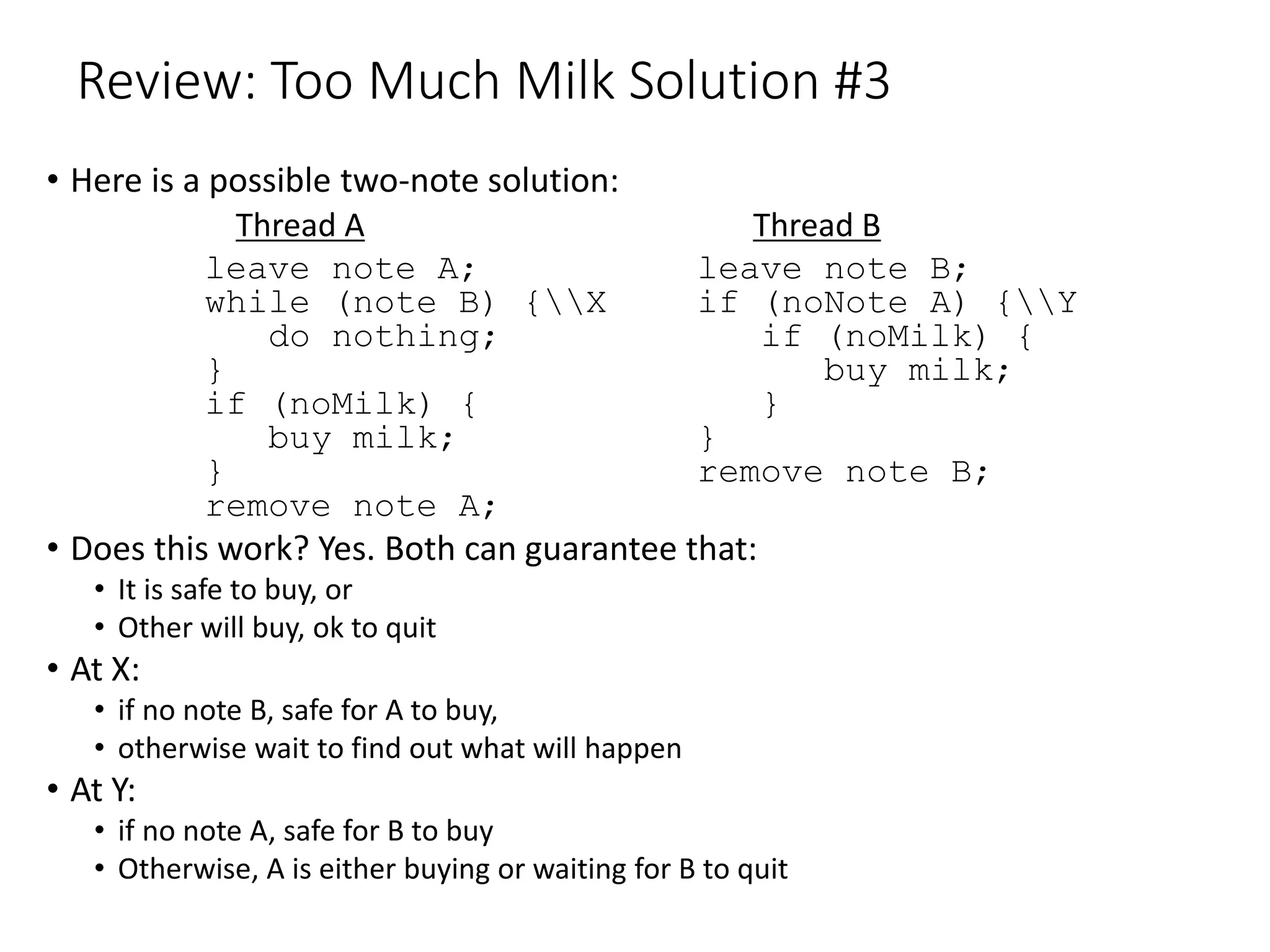

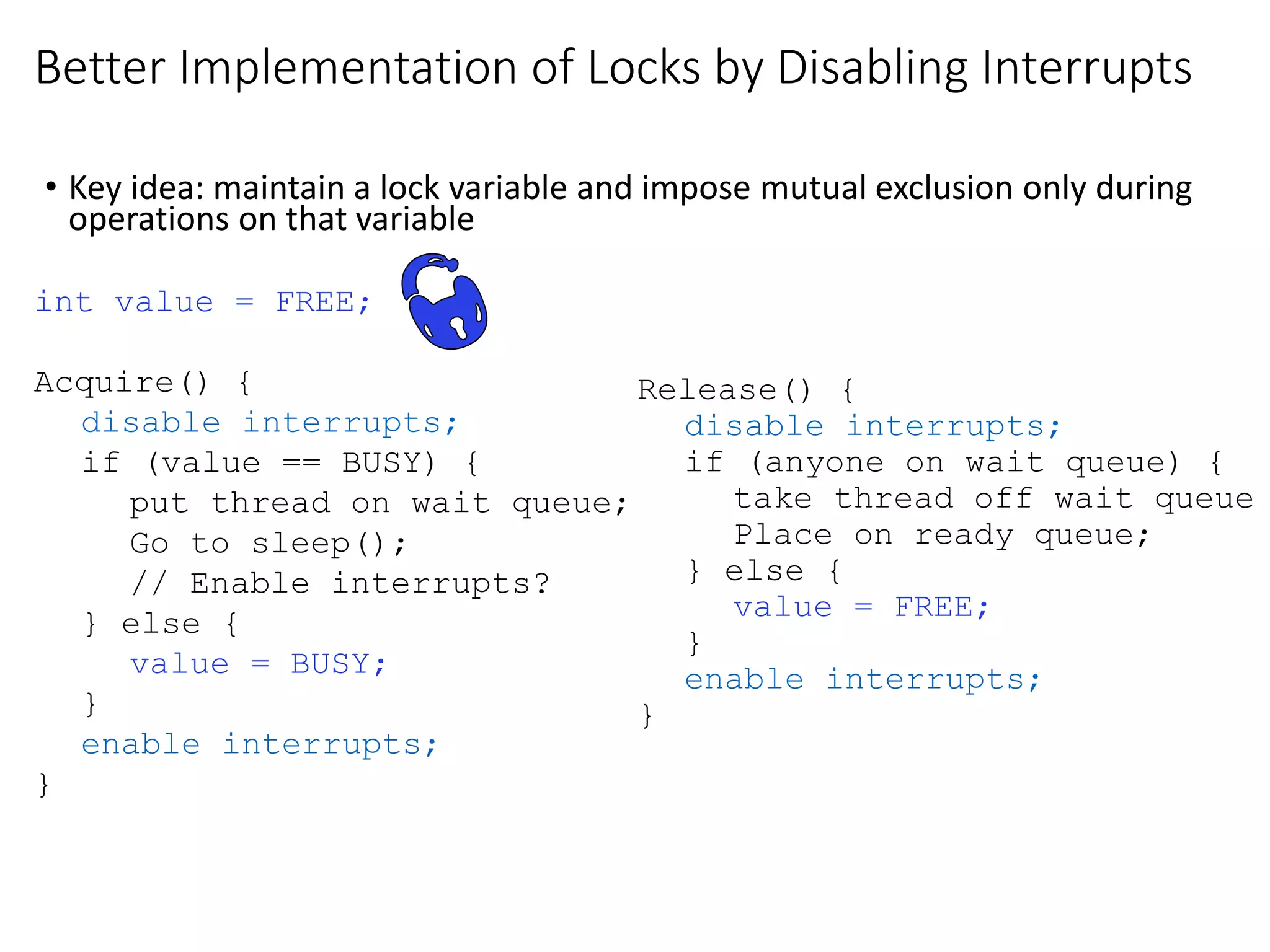

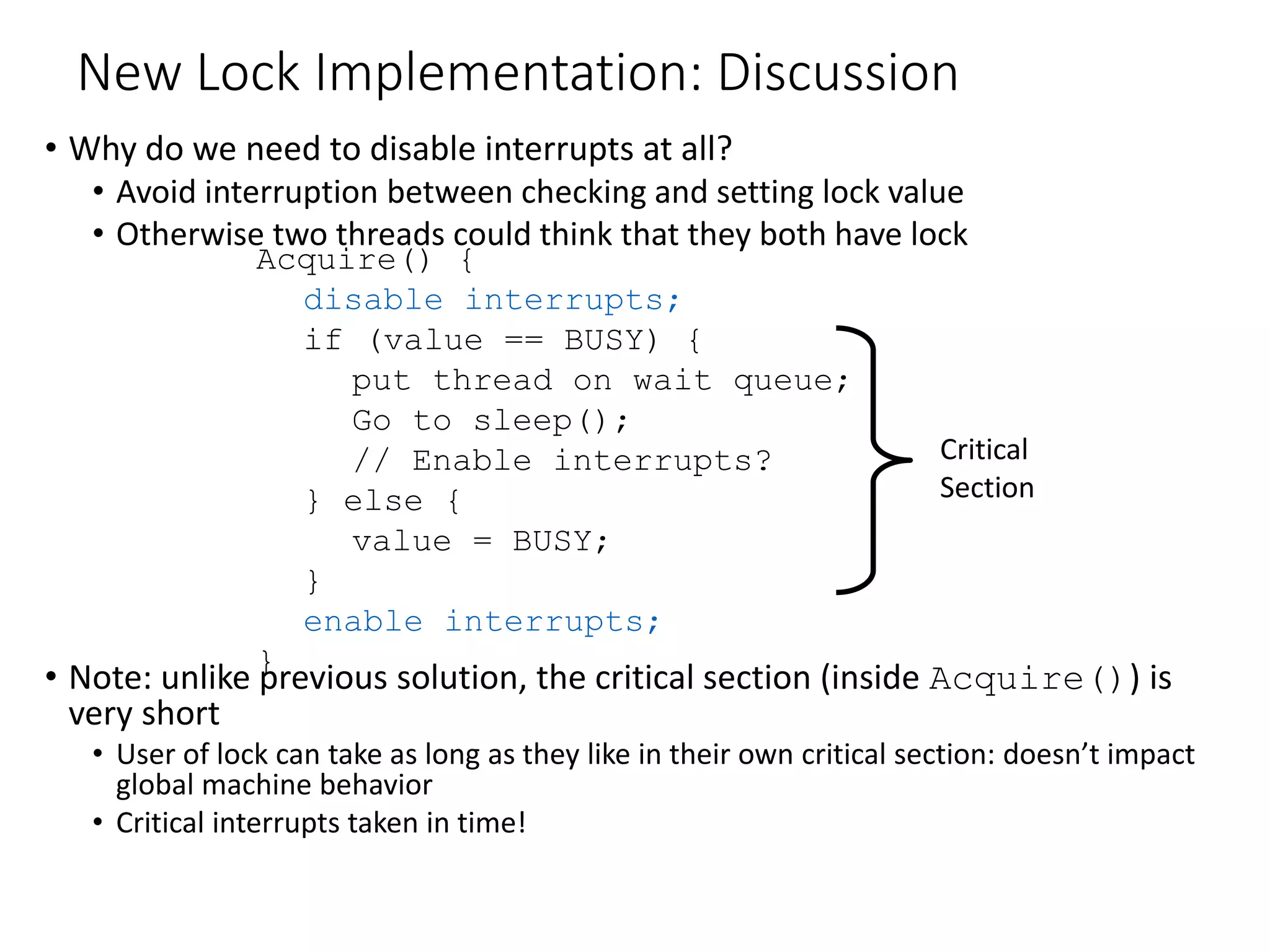

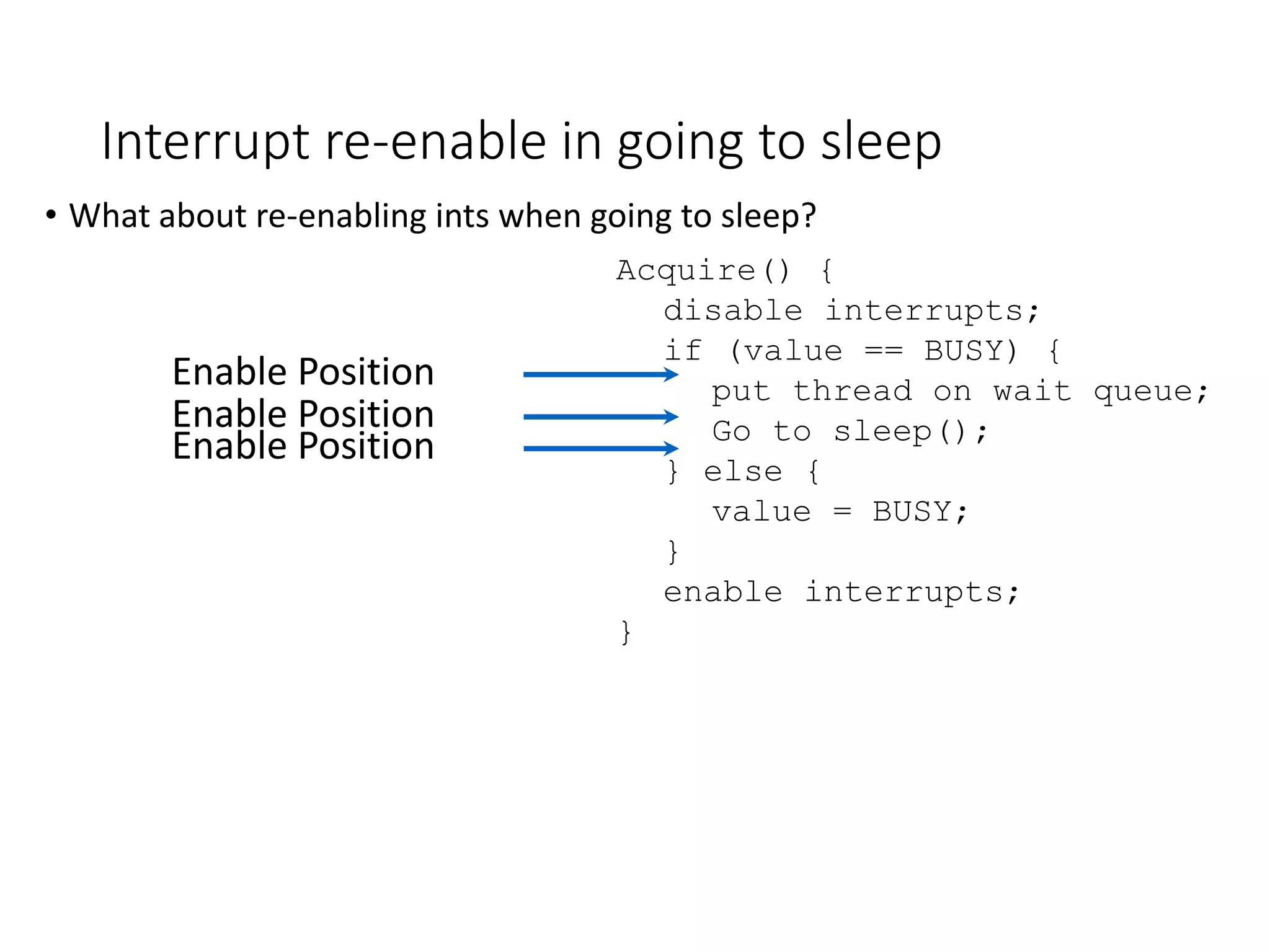

The document addresses synchronization problems in concurrent programming with threads, particularly focusing on atomic operations, locks, and semaphores. It examines various solutions to issues like shared state corruption and proposes higher-level abstractions for synchronization, including monitors and condition variables. The text also emphasizes the importance of avoiding busy-waiting and presents examples of producer-consumer scenarios to illustrate these concepts.

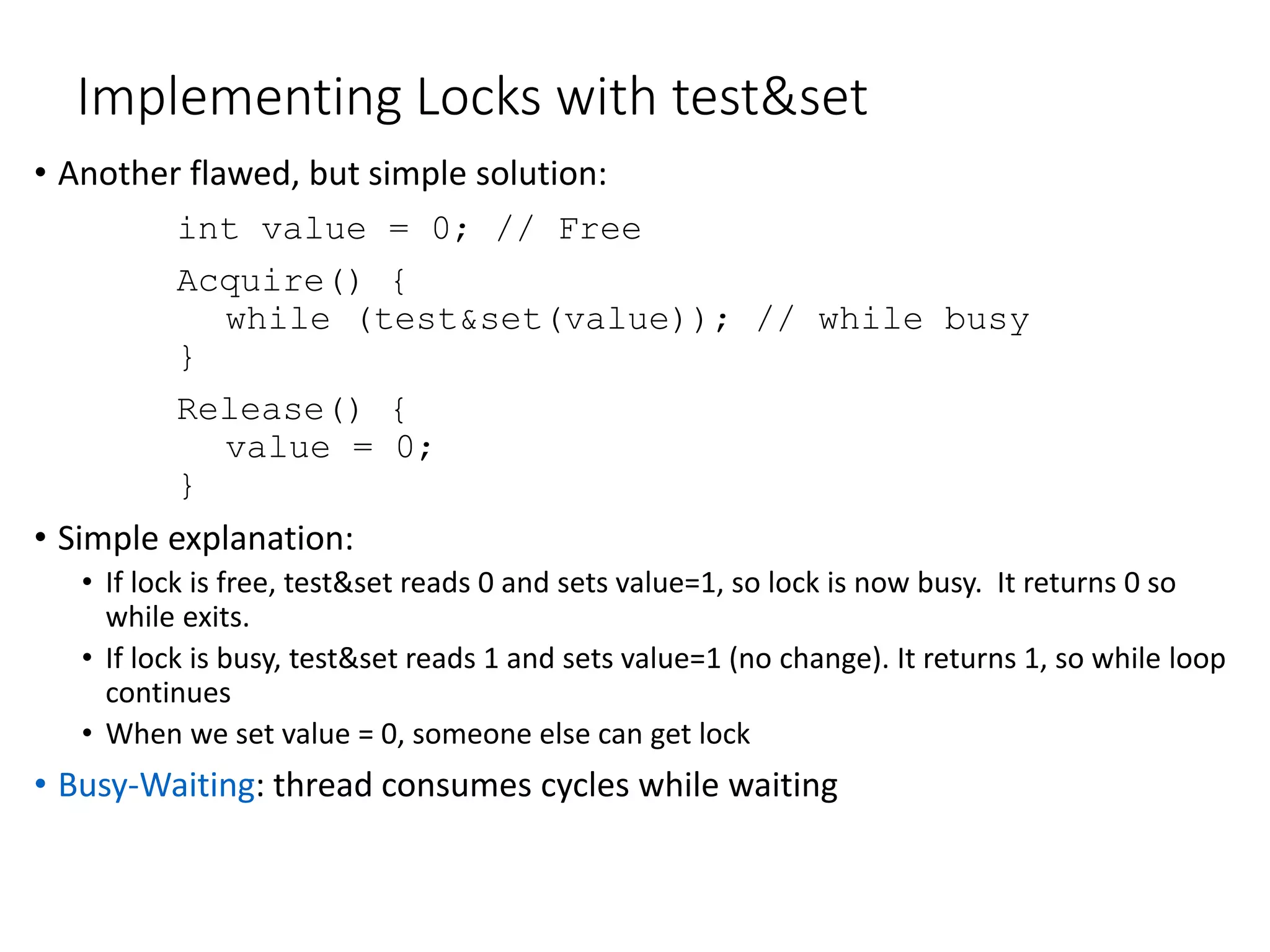

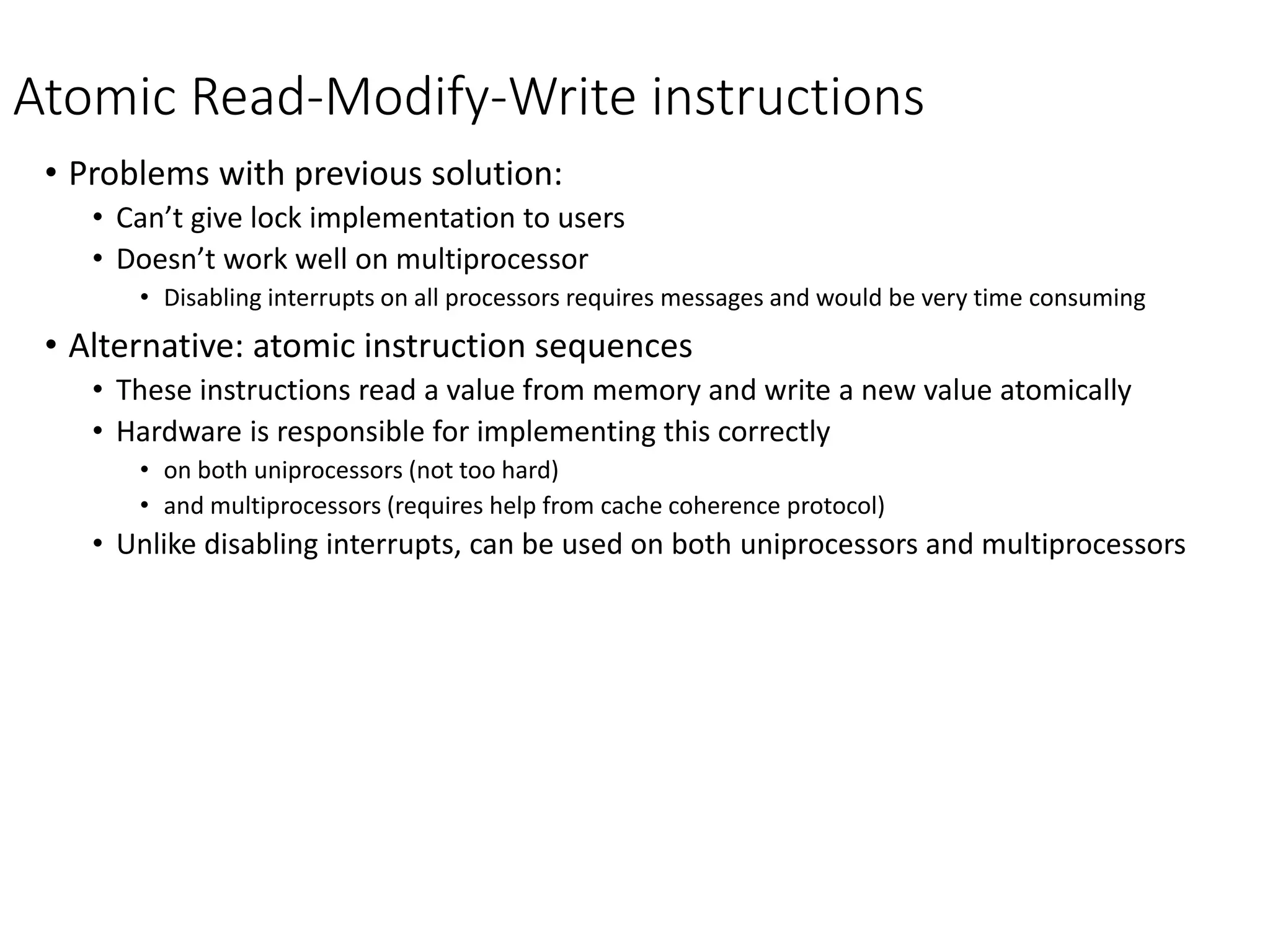

![Examples of Read-Modify-Write

• test&set (&address) { /* most architectures */

result = M[address];

M[address] = 1;

return result;

}

• swap (&address, register) { /* x86 */

temp = M[address];

M[address] = register;

register = temp;

}

• compare&swap (&address, reg1, reg2) { /* 68000 */

if (reg1 == M[address]) {

M[address] = reg2;

return success;

} else {

return failure;

}

}

• load-linked&store conditional(&address) {

/* R4000, alpha */

loop:

ll r1, M[address];

movi r2, 1; /* Can do arbitrary comp */

sc r2, M[address];

beqz r2, loop;

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/synchronizationproblemwiththreads-170503084738/75/Synchronization-problem-with-threads-14-2048.jpg)