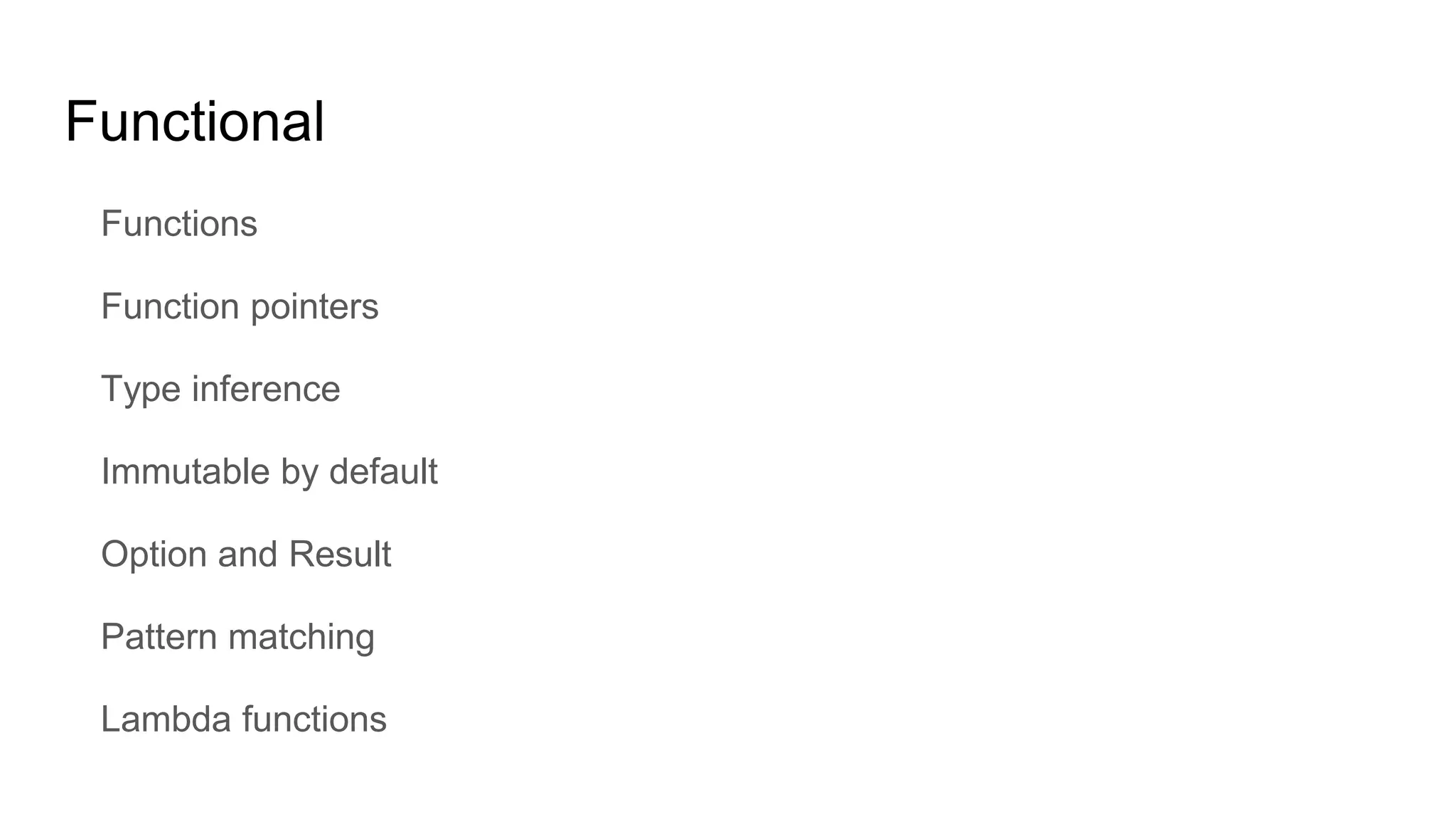

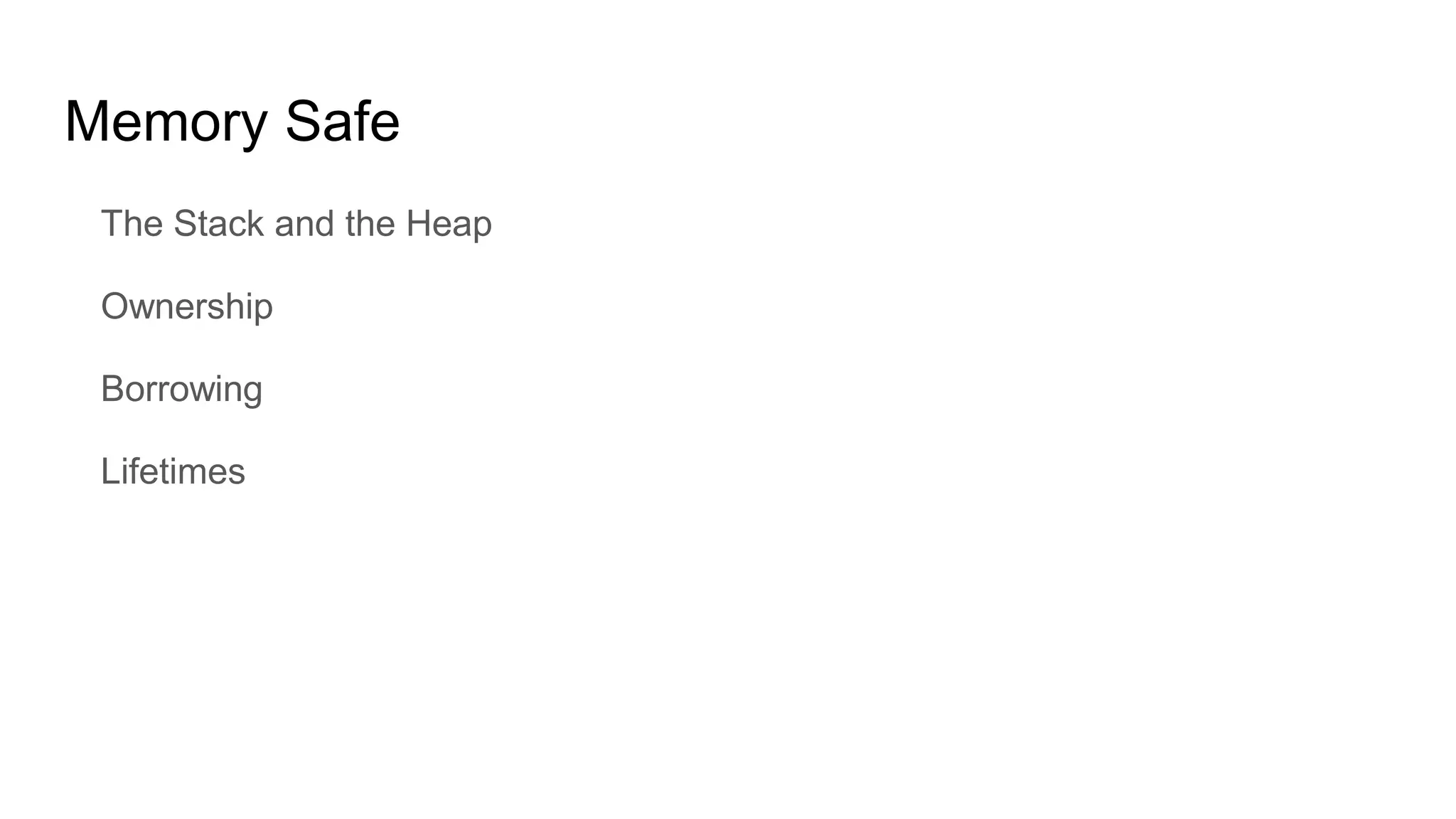

The document provides an overview of the Rust programming language. It describes how Rust grew out of a personal project at Mozilla in 2009. Rust aims to be a safe, concurrent, and practical language supporting multiple paradigms. It uses concepts like ownership and borrowing to prevent data races at compile time. Rust also features traits, generics, pattern matching, and lifetimes to manage memory in a flexible yet deterministic manner.

![Ownership

let v = vec![1, 2, 3];

let v2 = v;

println!("v[0] is: {}", v[0]);

error: use of moved value: `v`

println!("v[0] is: {}", v[0]);

^](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rust-160623130821/75/Rust-Intro-37-2048.jpg)

![Ownership

fn take(v: Vec<i32>) {

// what happens here isn’t important.

}

let v = vec![1, 2, 3];

take(v);

println!("v[0] is: {}", v[0]);

Same error: ‘use of moved value’.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rust-160623130821/75/Rust-Intro-38-2048.jpg)

![Borrowing

fn foo(v1: Vec<i32>, v2: Vec<i32>) -> (Vec<i32>, Vec<i32>, i32) {

// do stuff with v1 and v2

// hand back ownership, and the result of our function

(v1, v2, 42)

}

let v1 = vec![1, 2, 3];

let v2 = vec![1, 2, 3];

let (v1, v2, answer) = foo(v1, v2);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rust-160623130821/75/Rust-Intro-39-2048.jpg)

![Borrowing

fn foo(v1: &Vec<i32>, v2: &Vec<i32>) -> i32 {

// do stuff with v1 and v2

// return the answer

42

}

let v1 = vec![1, 2, 3];

let v2 = vec![1, 2, 3];

let answer = foo(&v1, &v2);

// we can use v1 and v2 here!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rust-160623130821/75/Rust-Intro-40-2048.jpg)

![&mut references

fn foo(v: &Vec<i32>) {

v.push(5);

}

let v = vec![];

foo(&v);

errors with:

error: cannot borrow immutable borrowed content `*v` as mutable

v.push(5);

^](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rust-160623130821/75/Rust-Intro-41-2048.jpg)

![&mut references

fn foo(v: &mut Vec<i32>) {

v.push(5);

}

let mut v = vec![];

foo(&mut v);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rust-160623130821/75/Rust-Intro-42-2048.jpg)