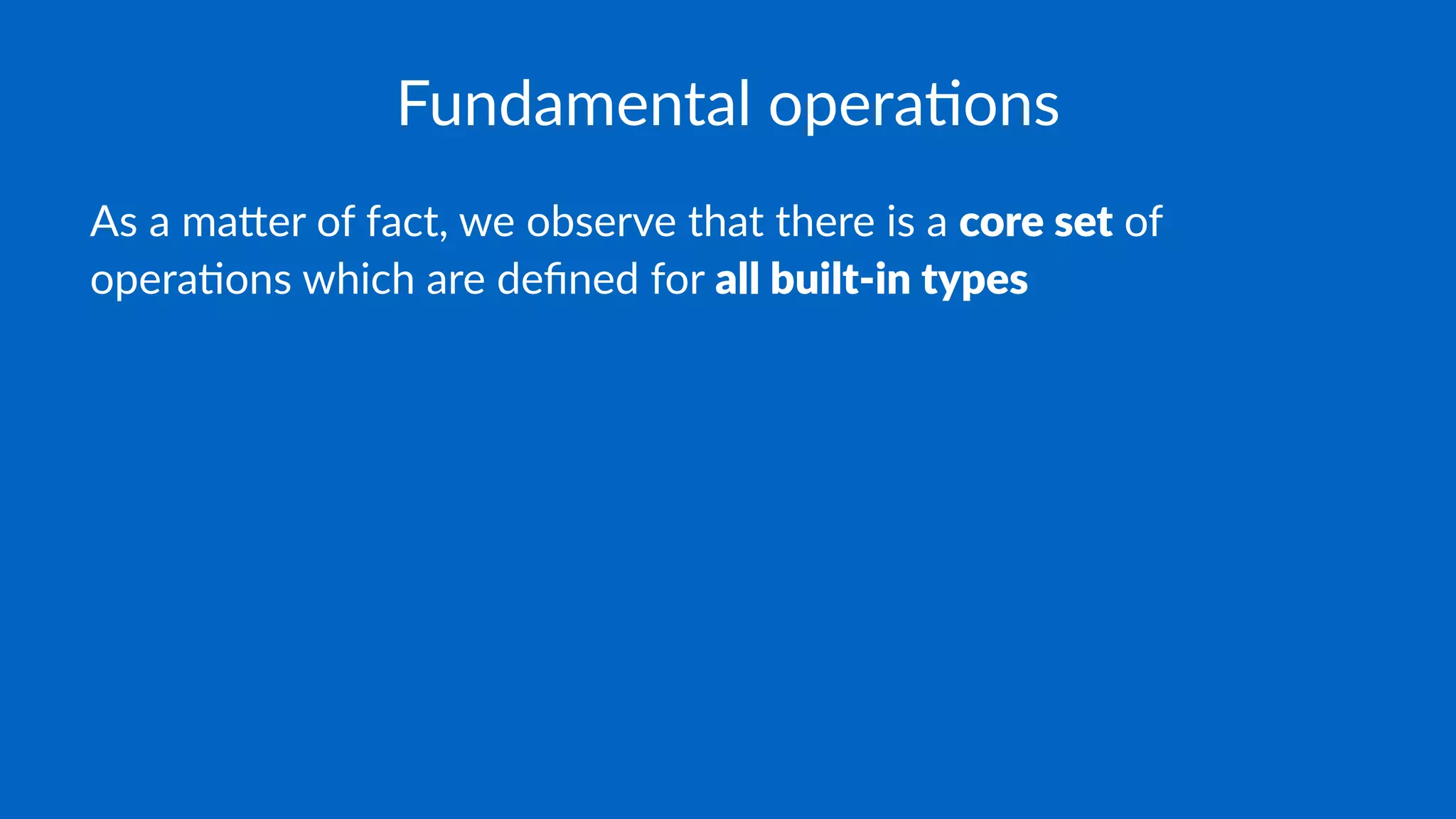

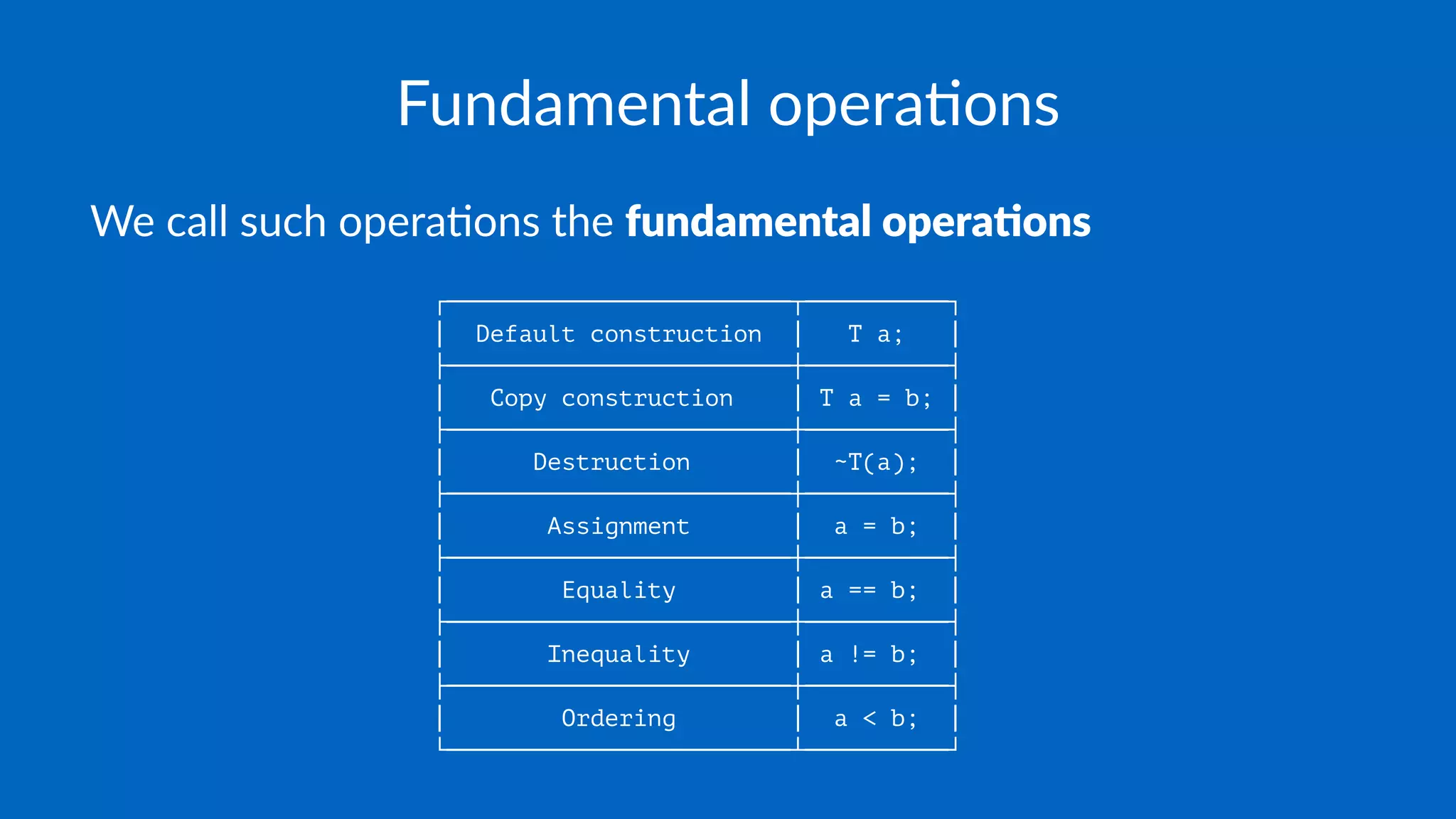

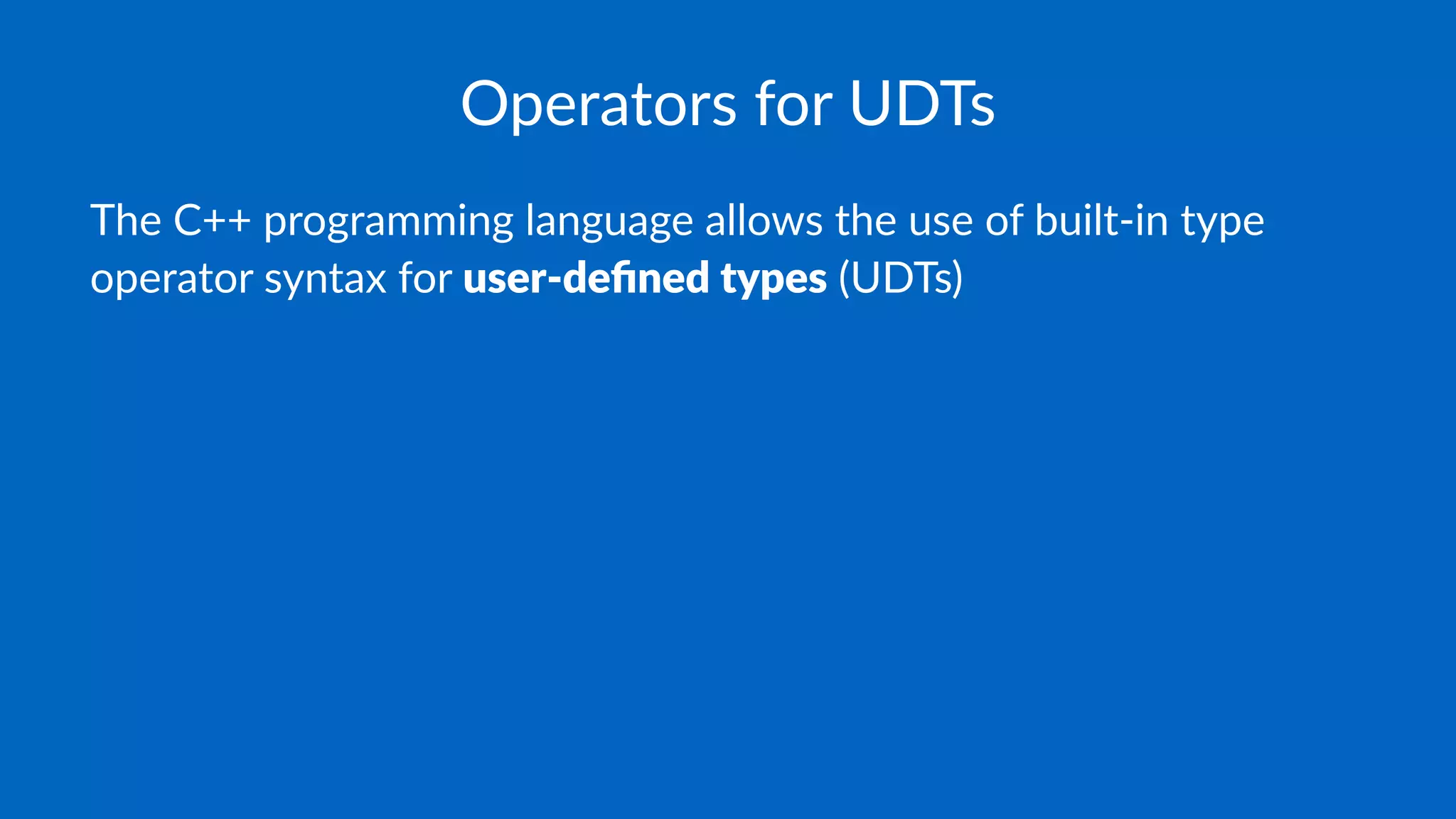

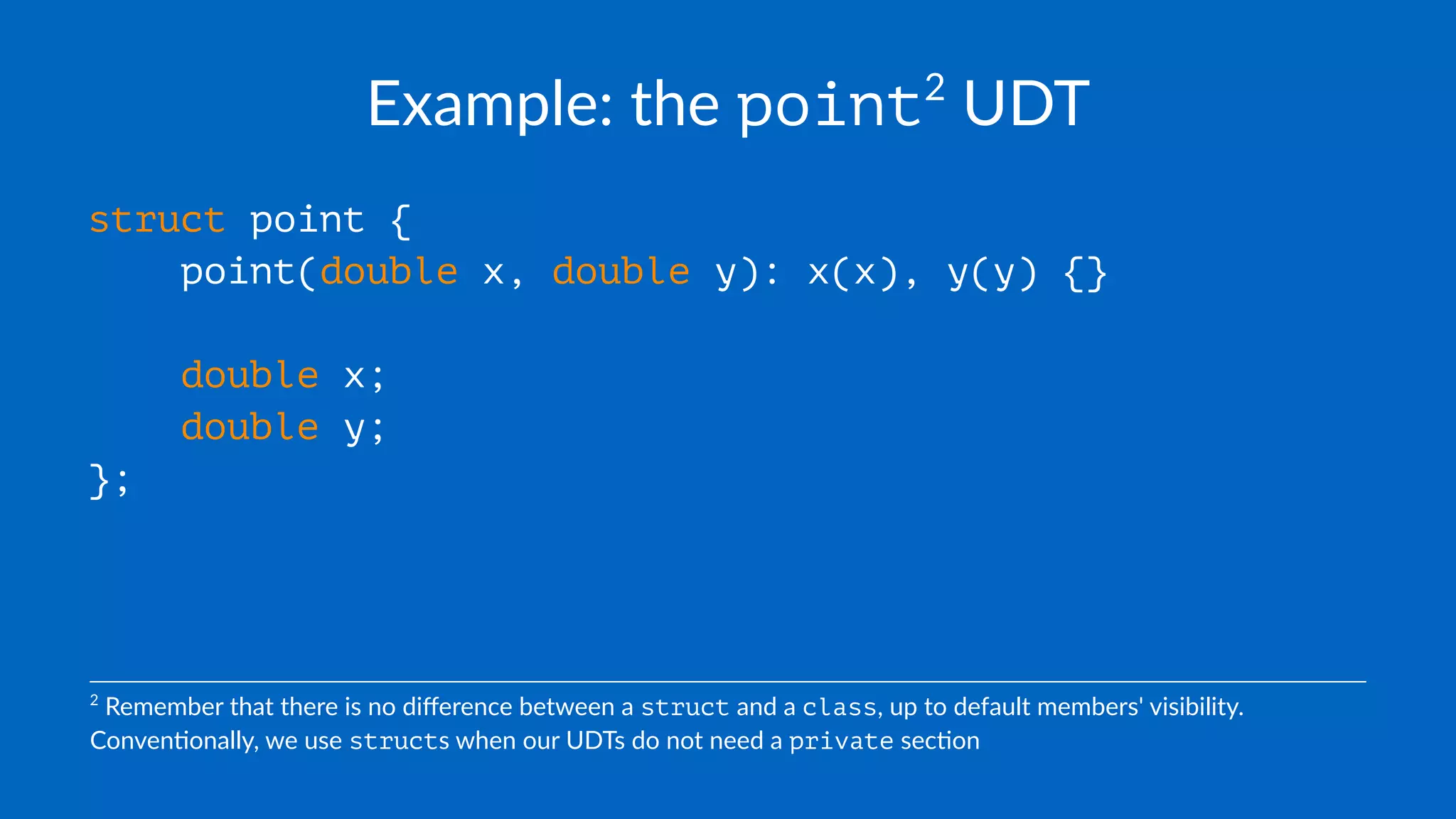

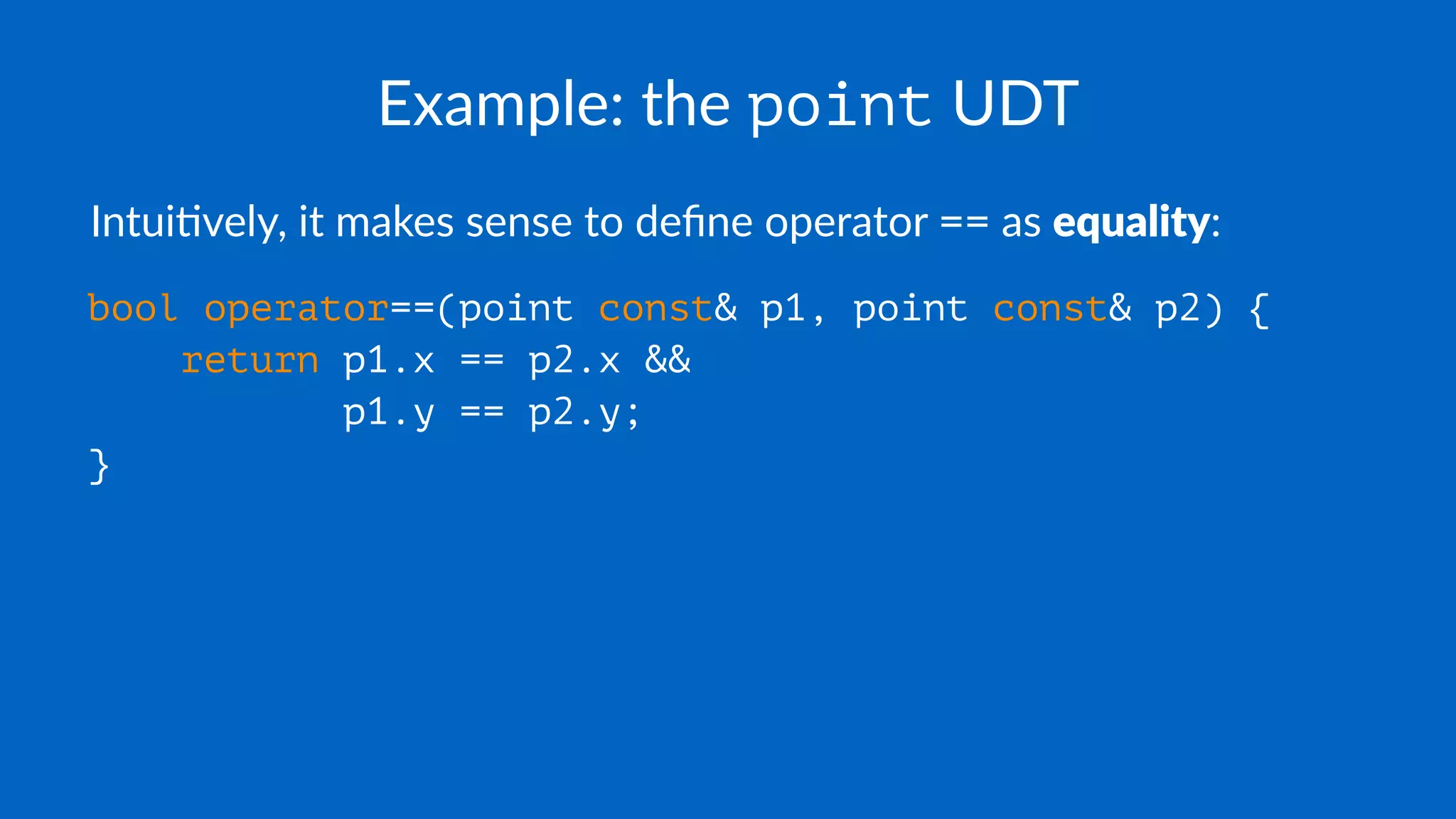

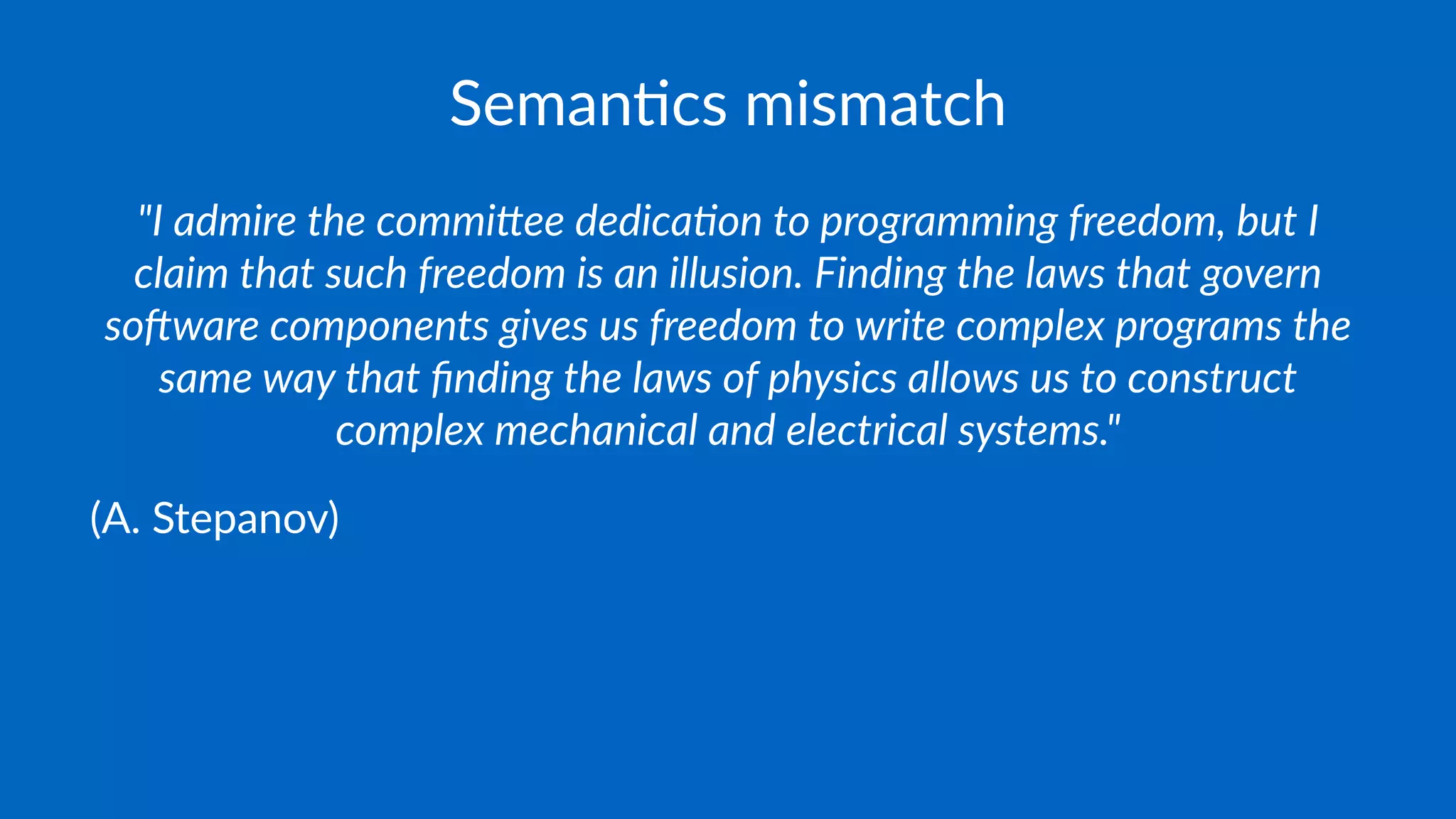

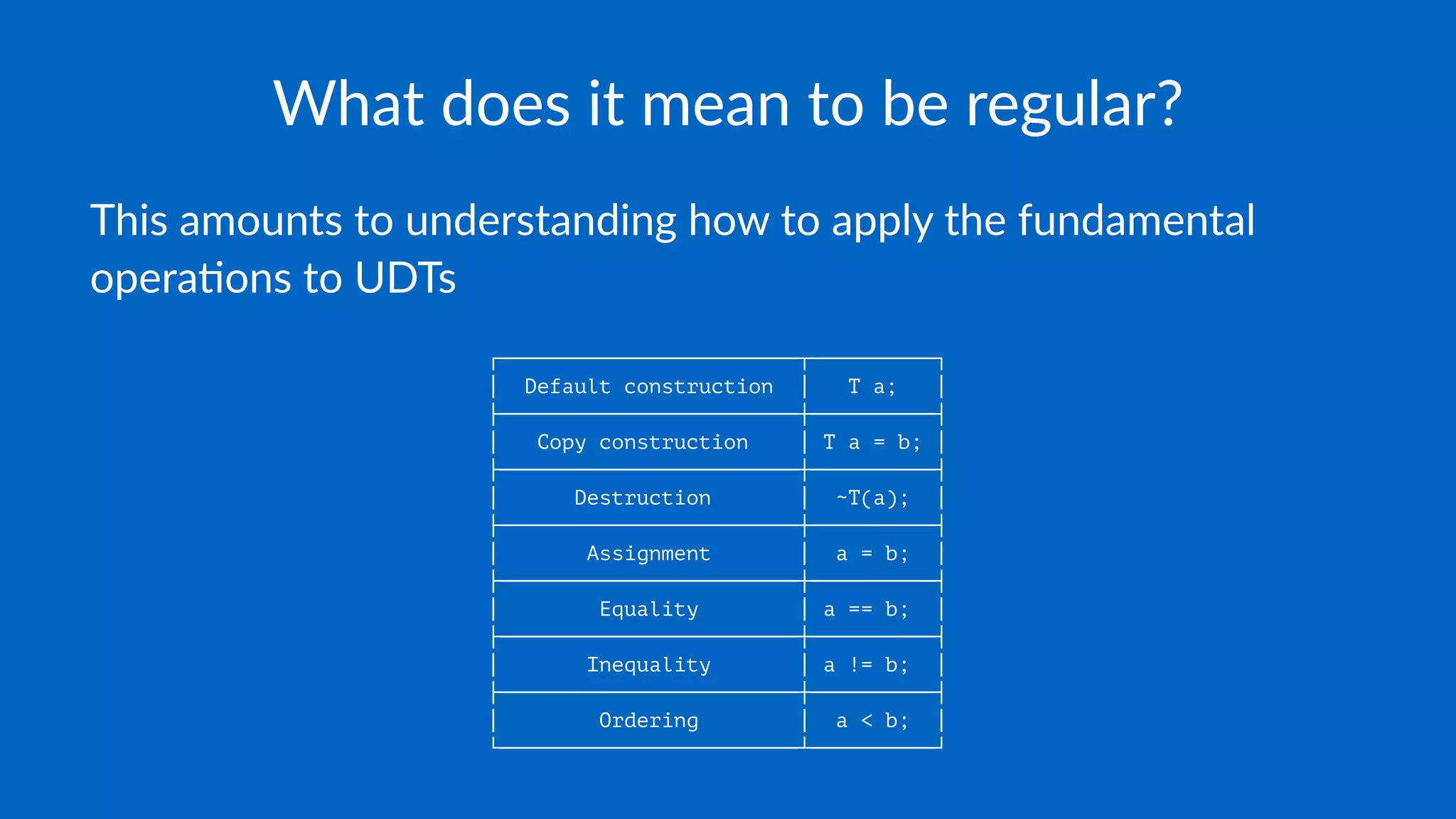

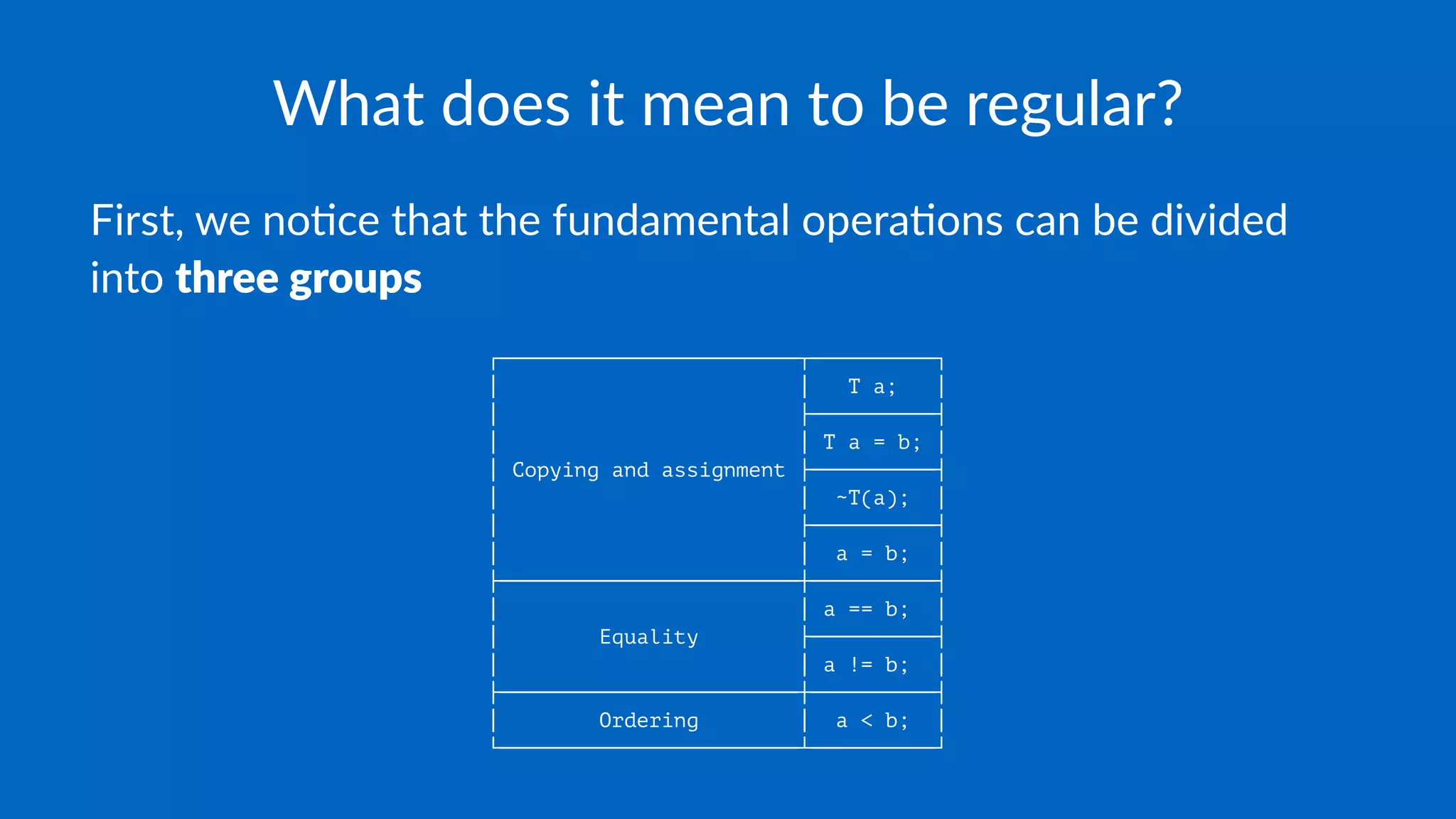

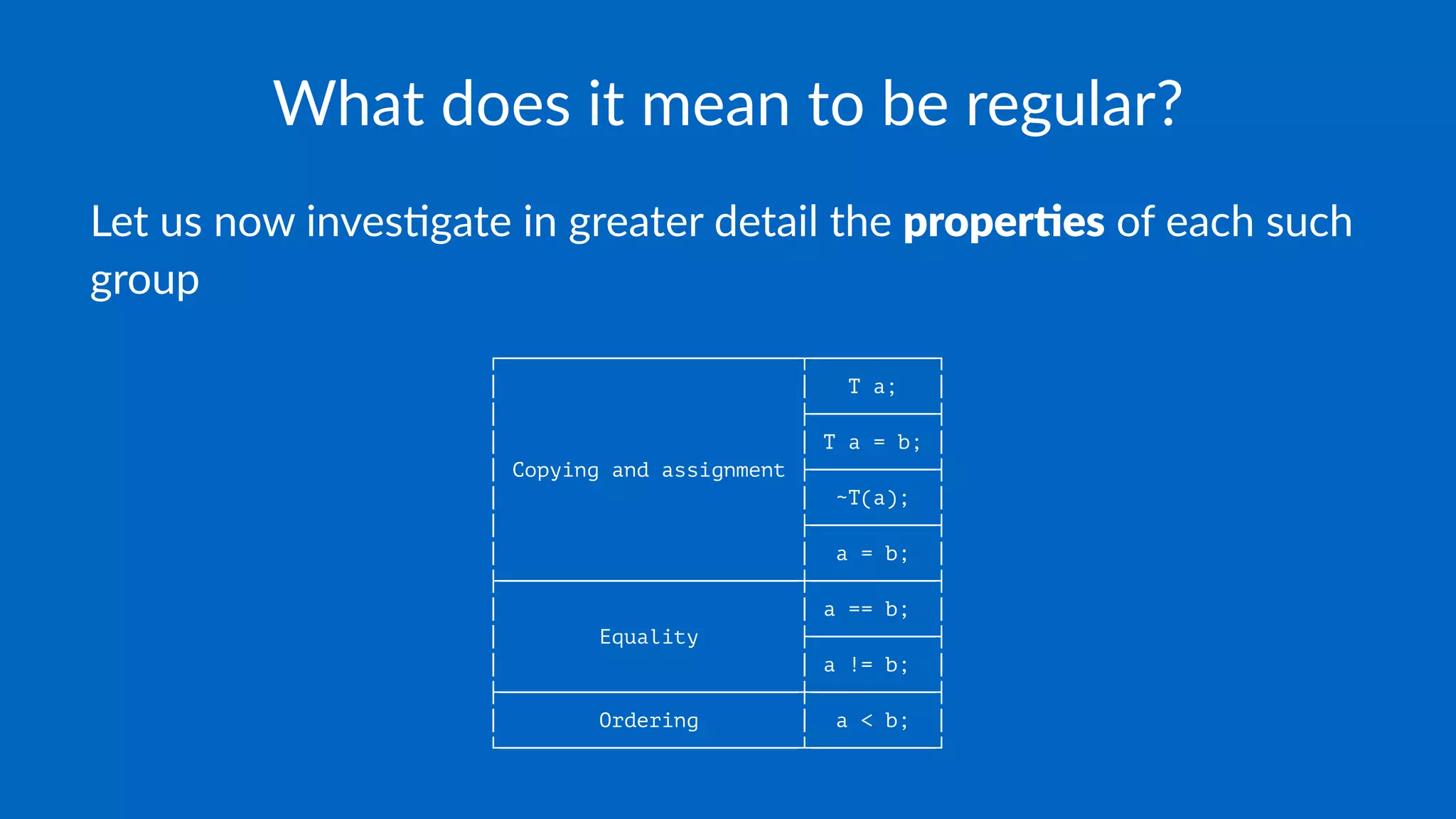

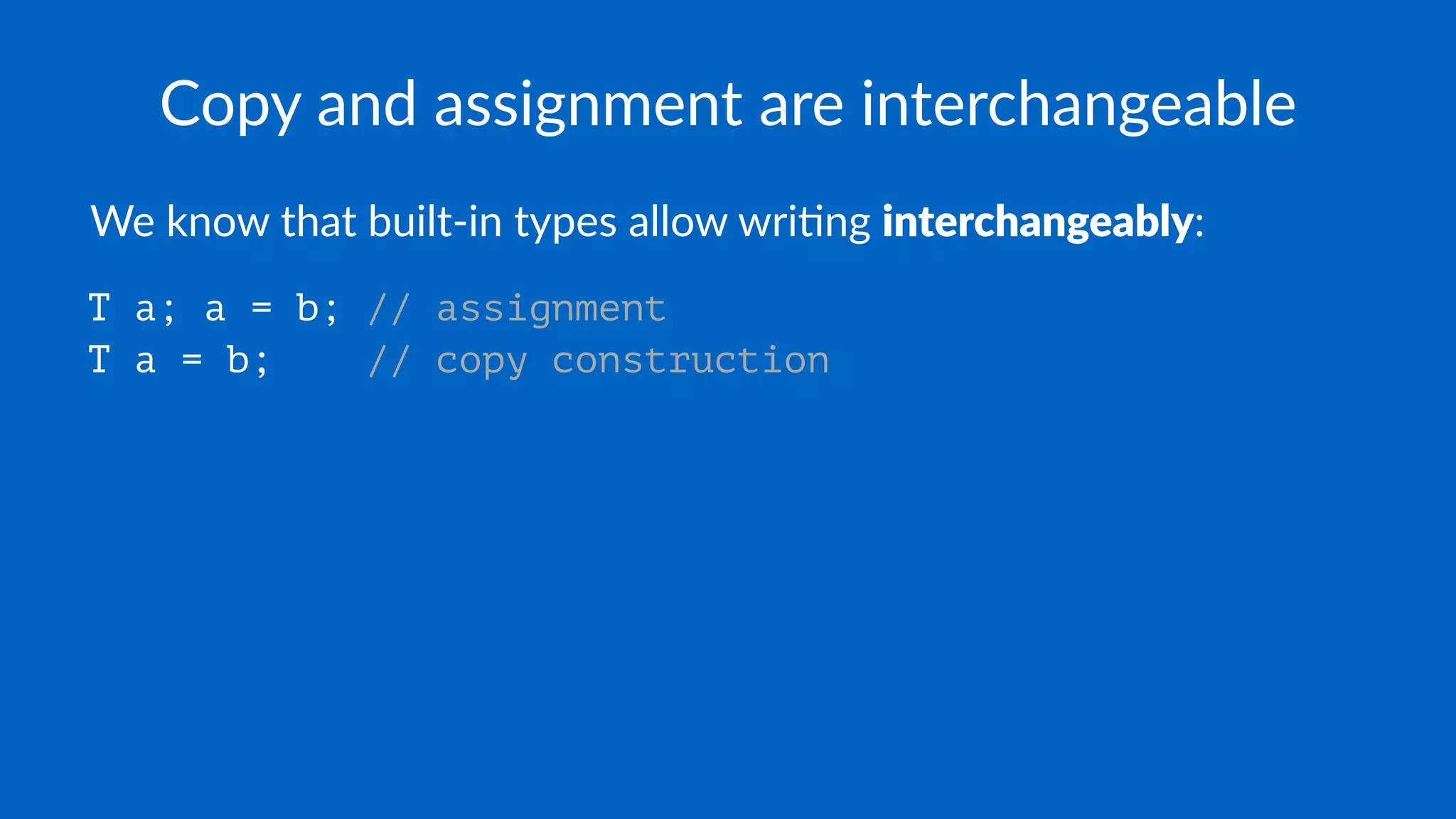

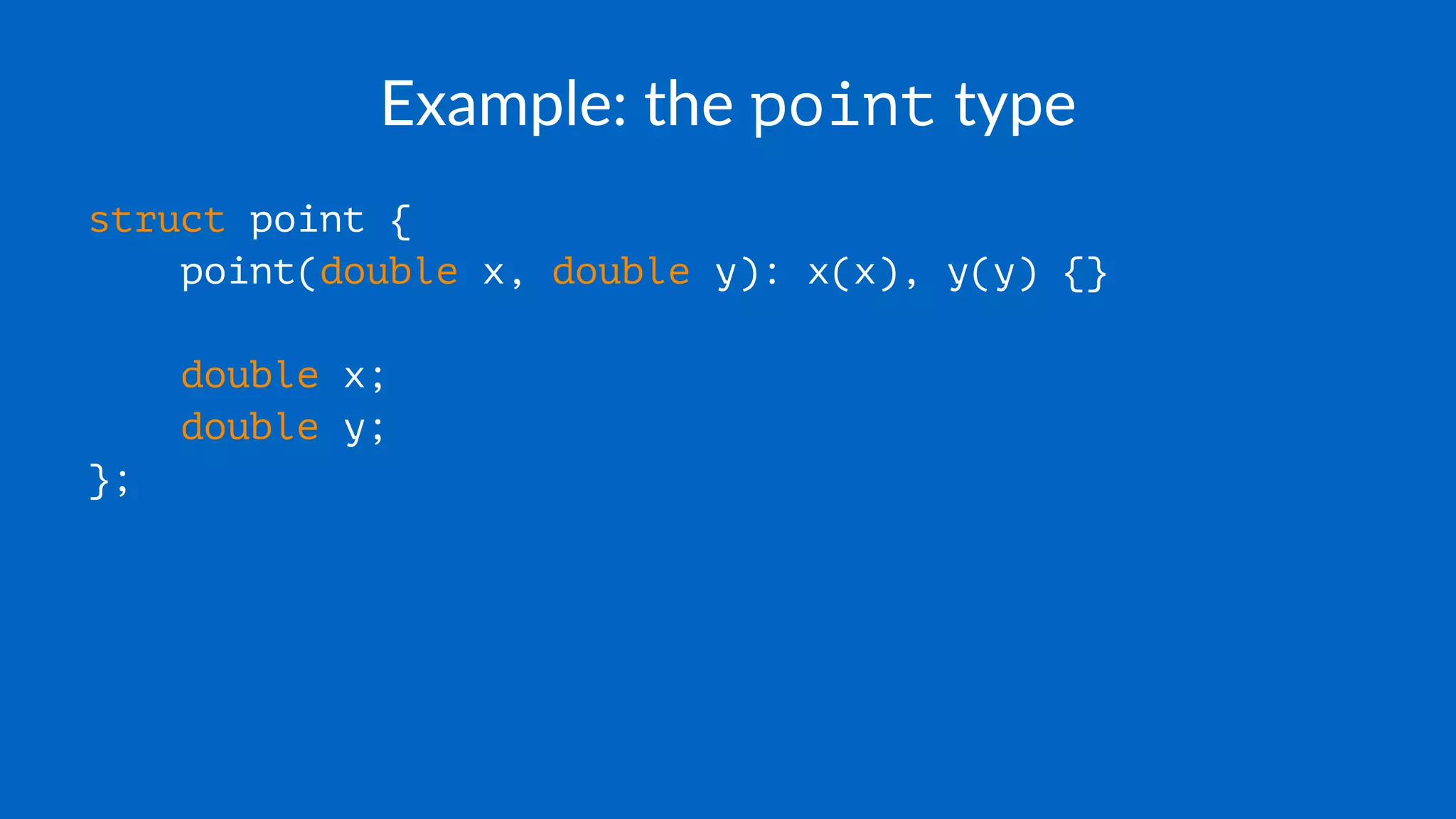

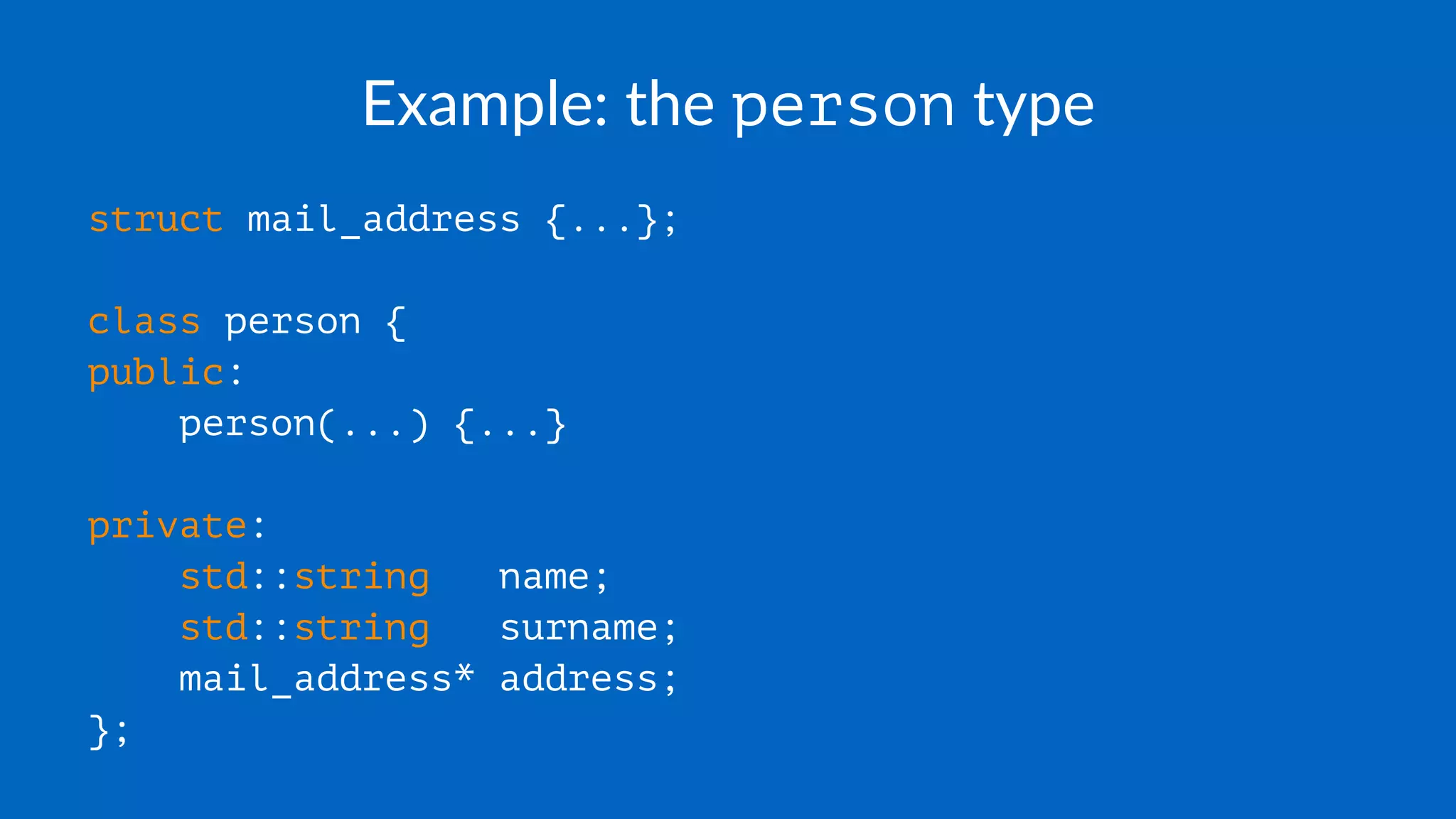

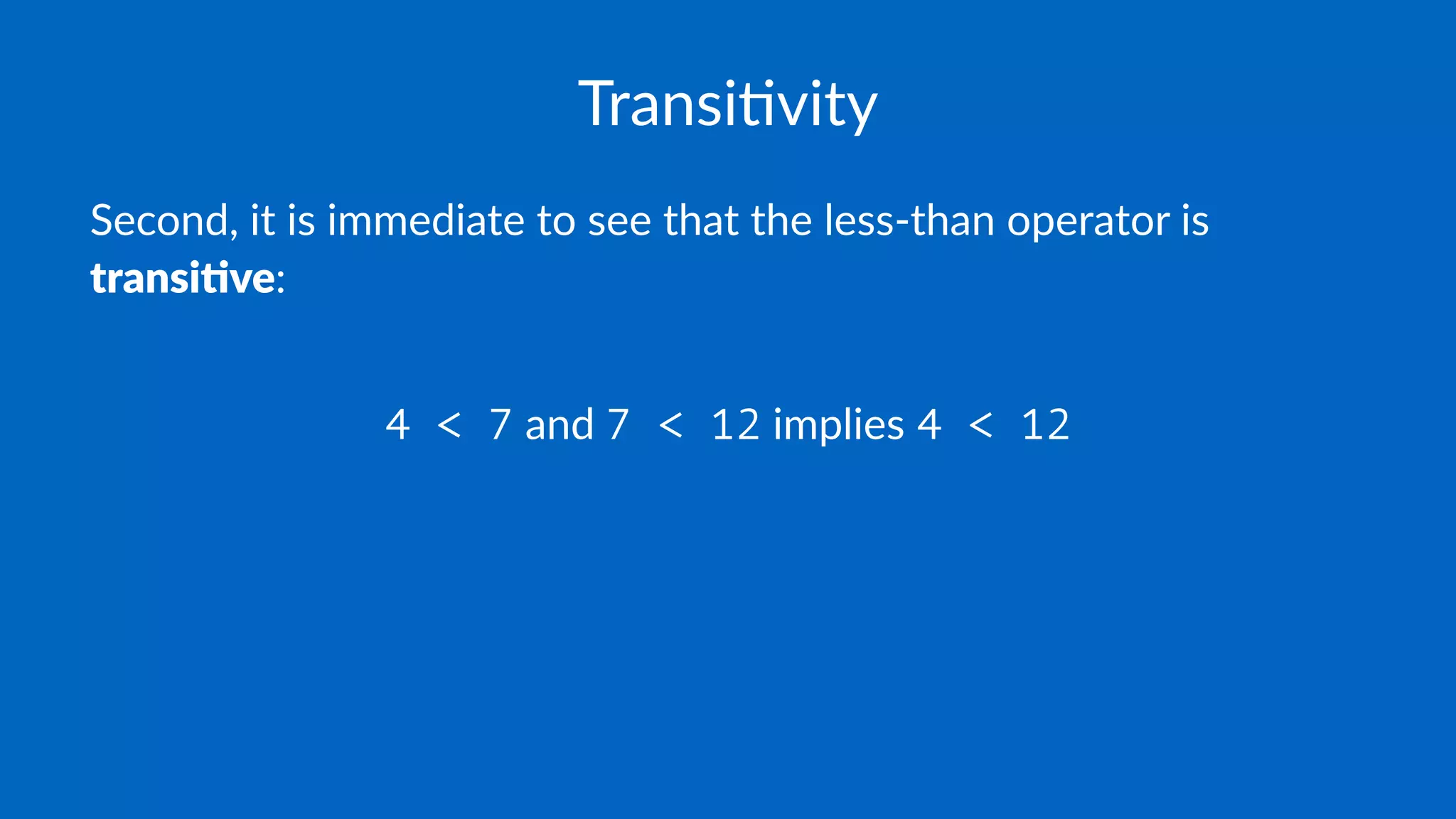

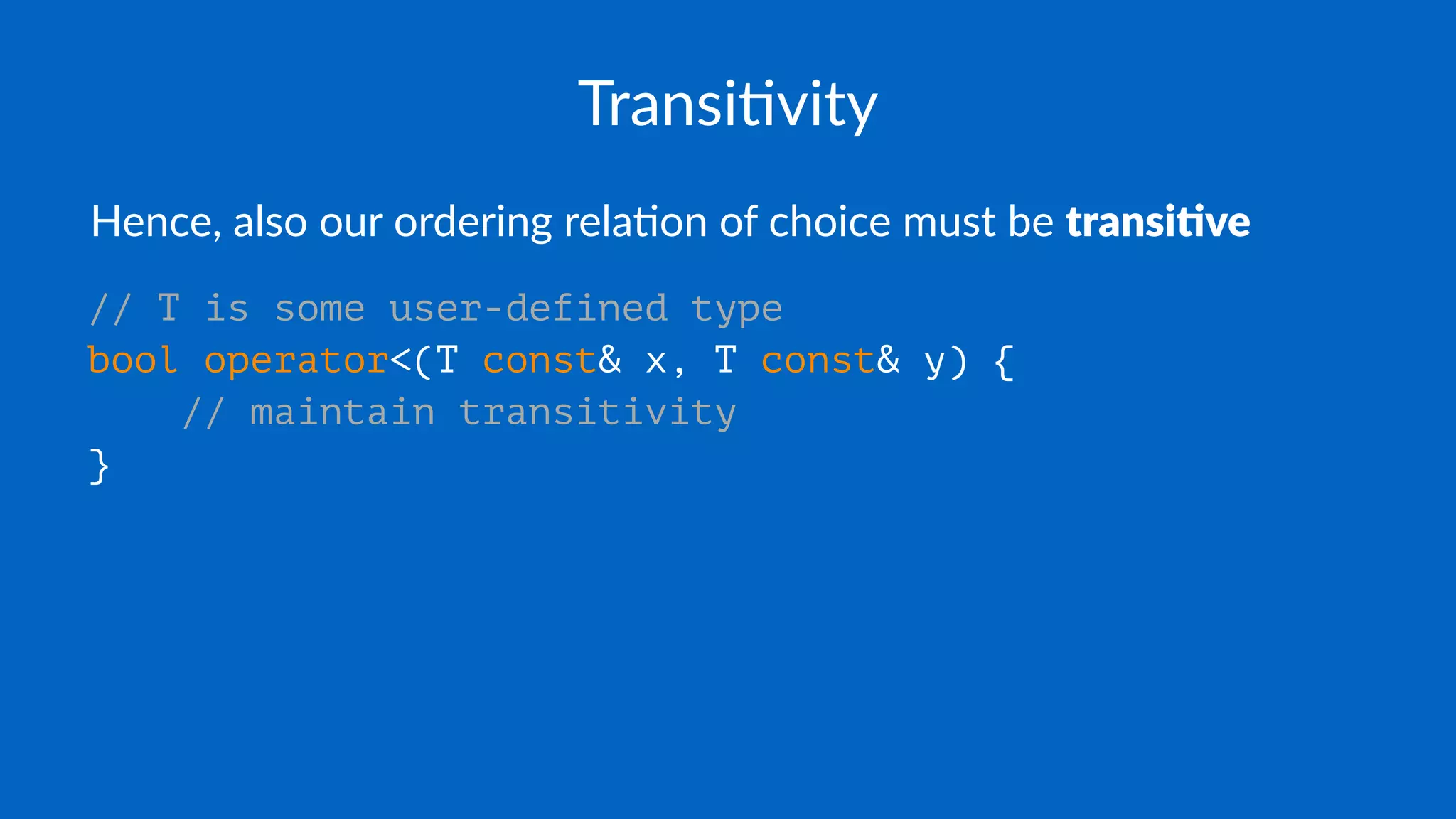

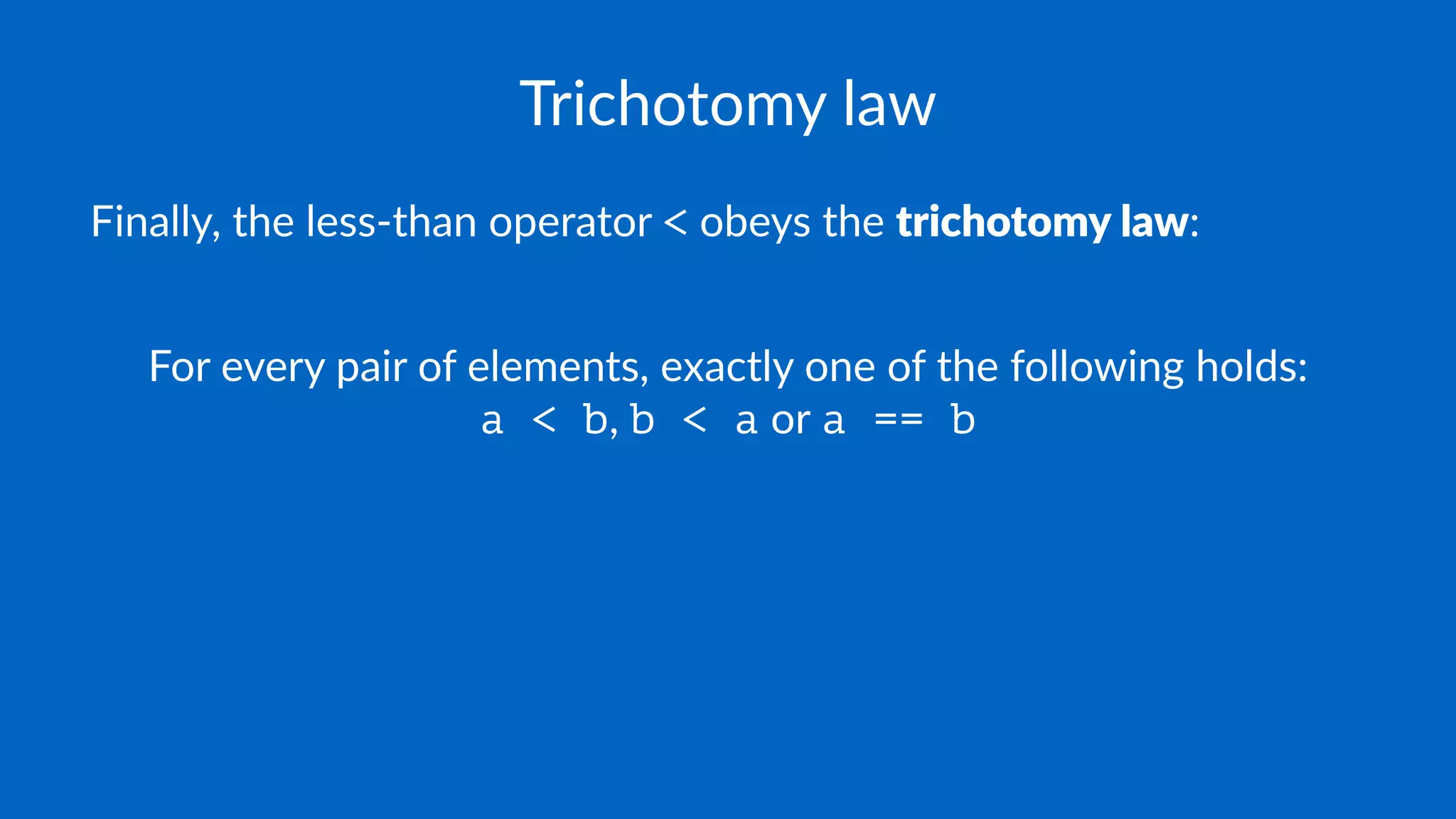

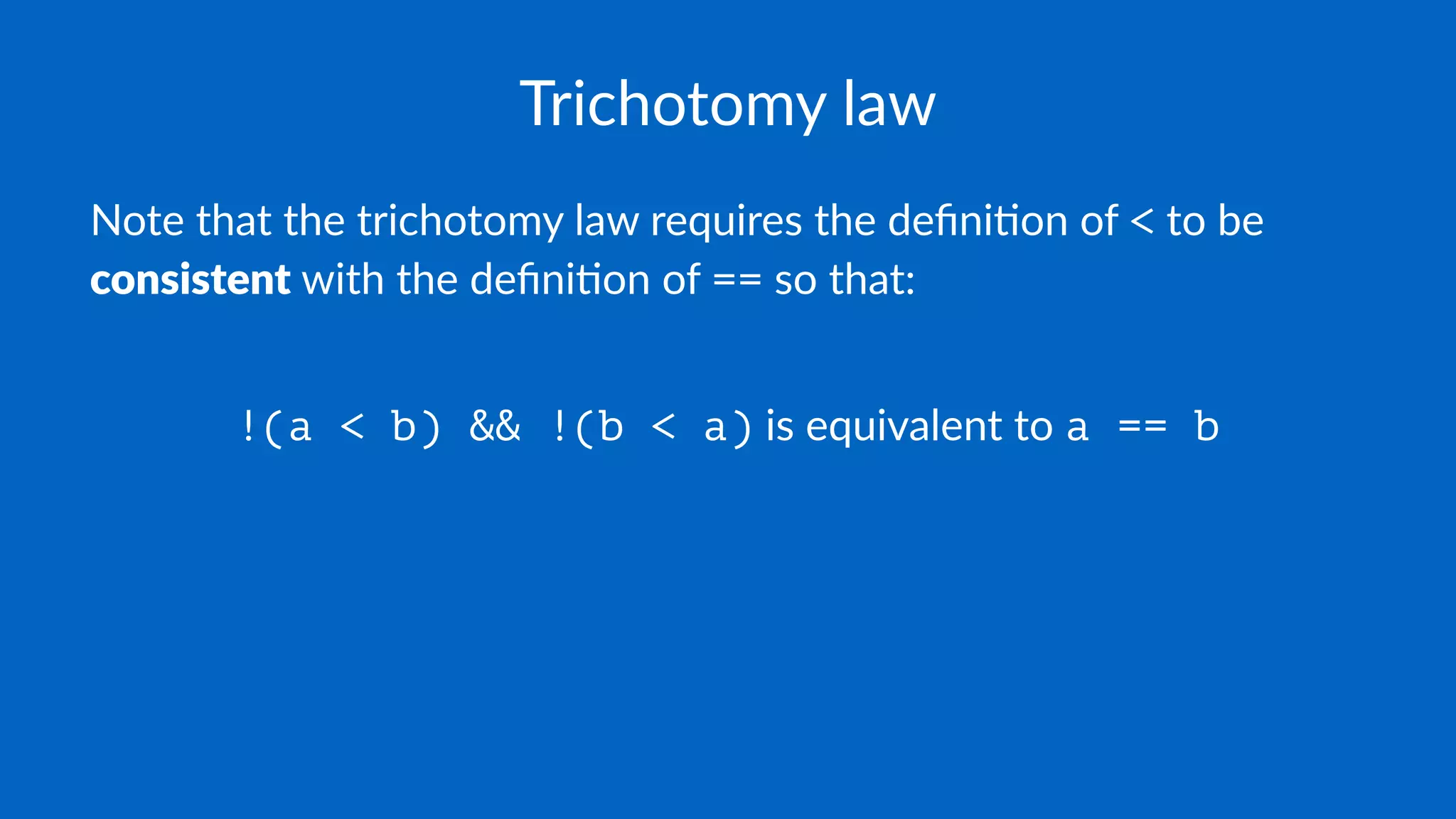

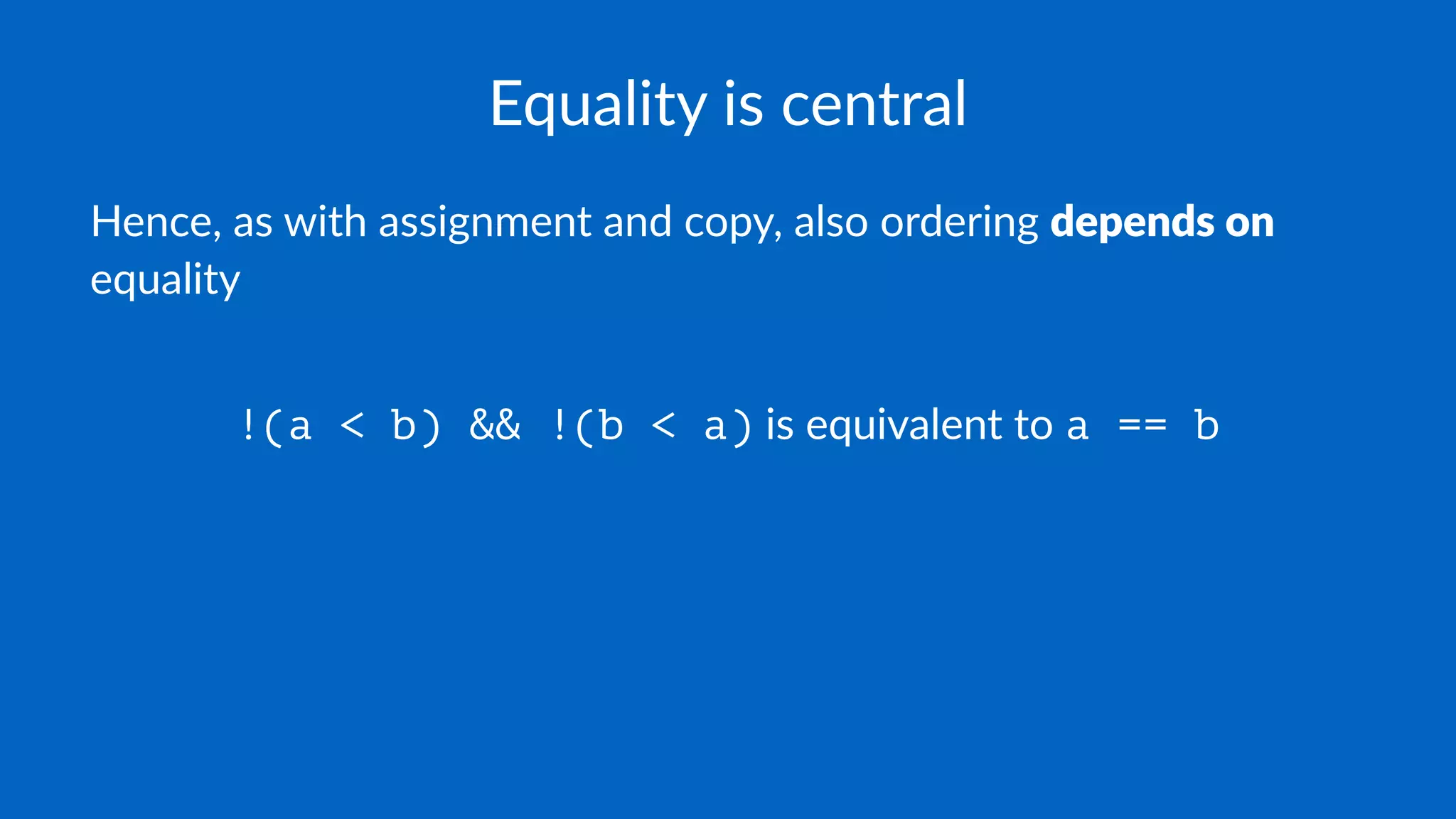

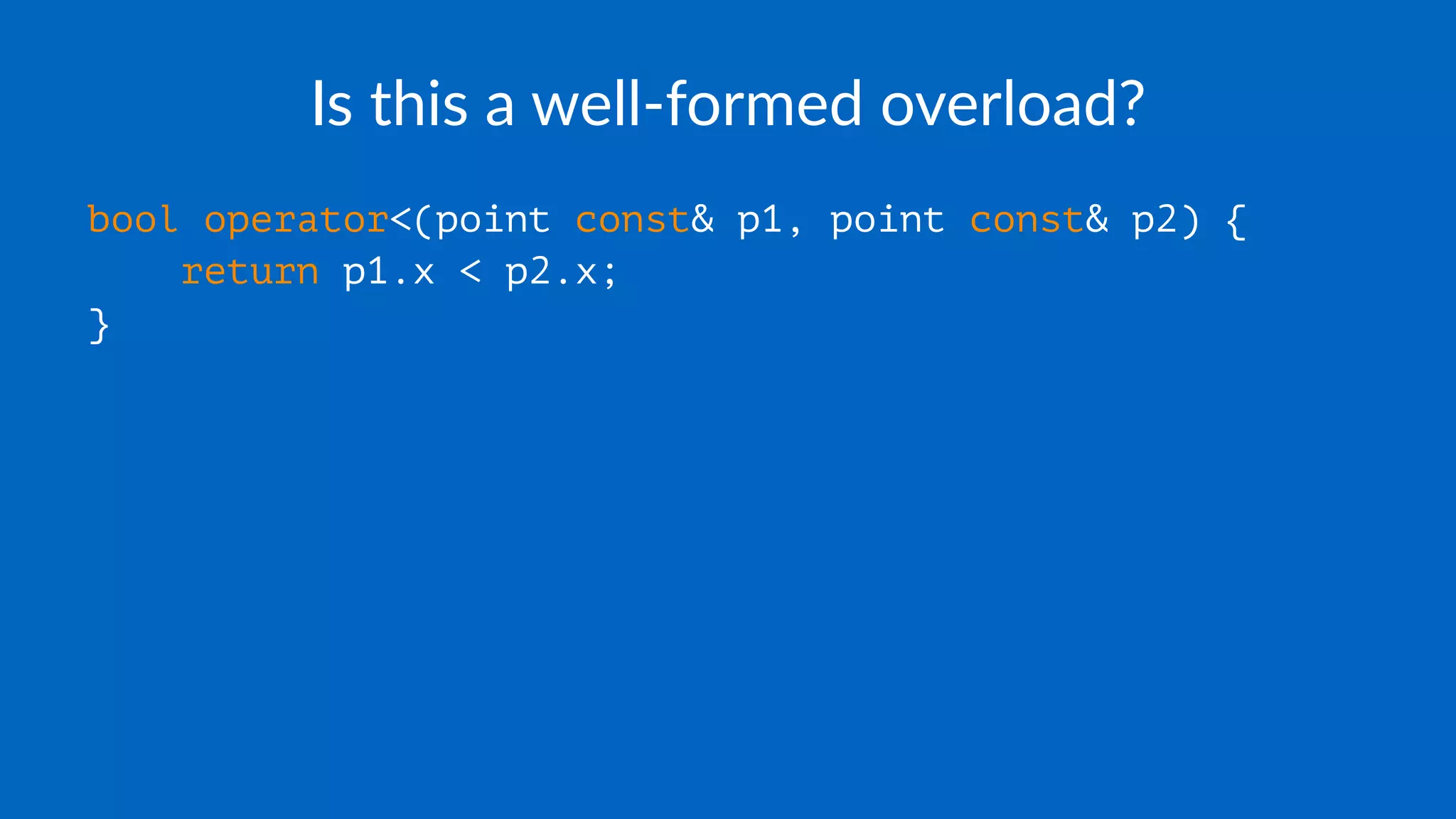

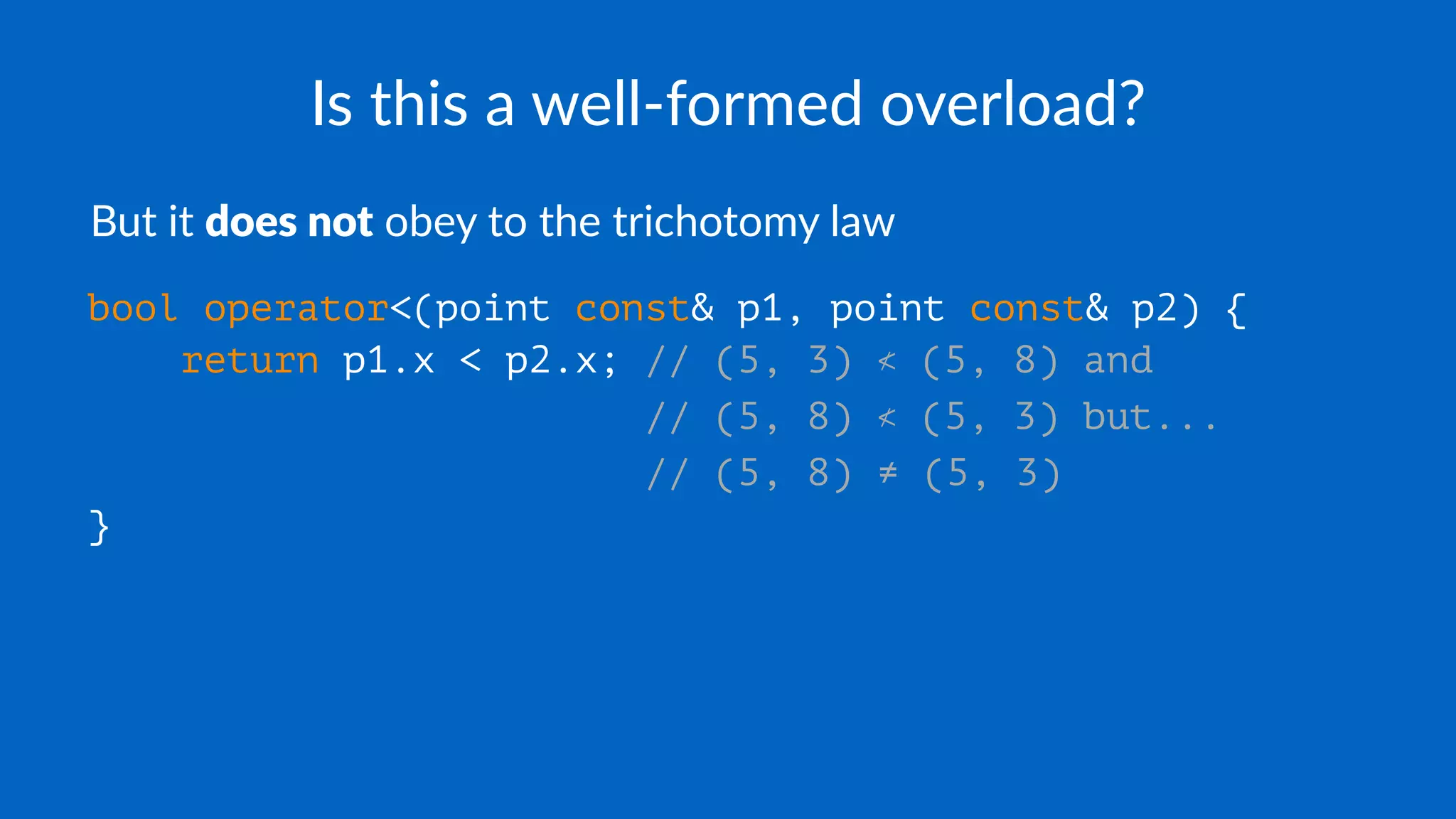

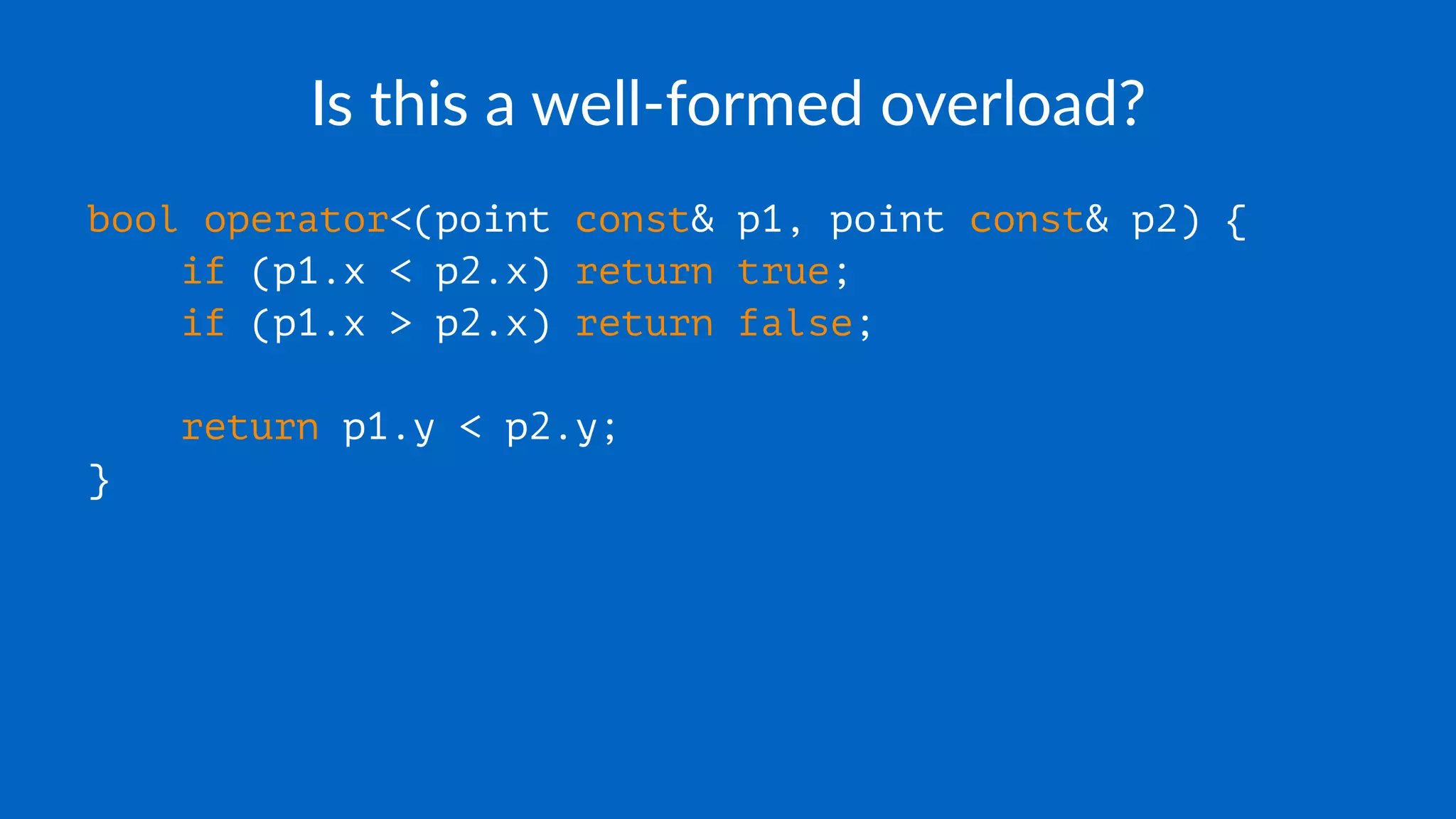

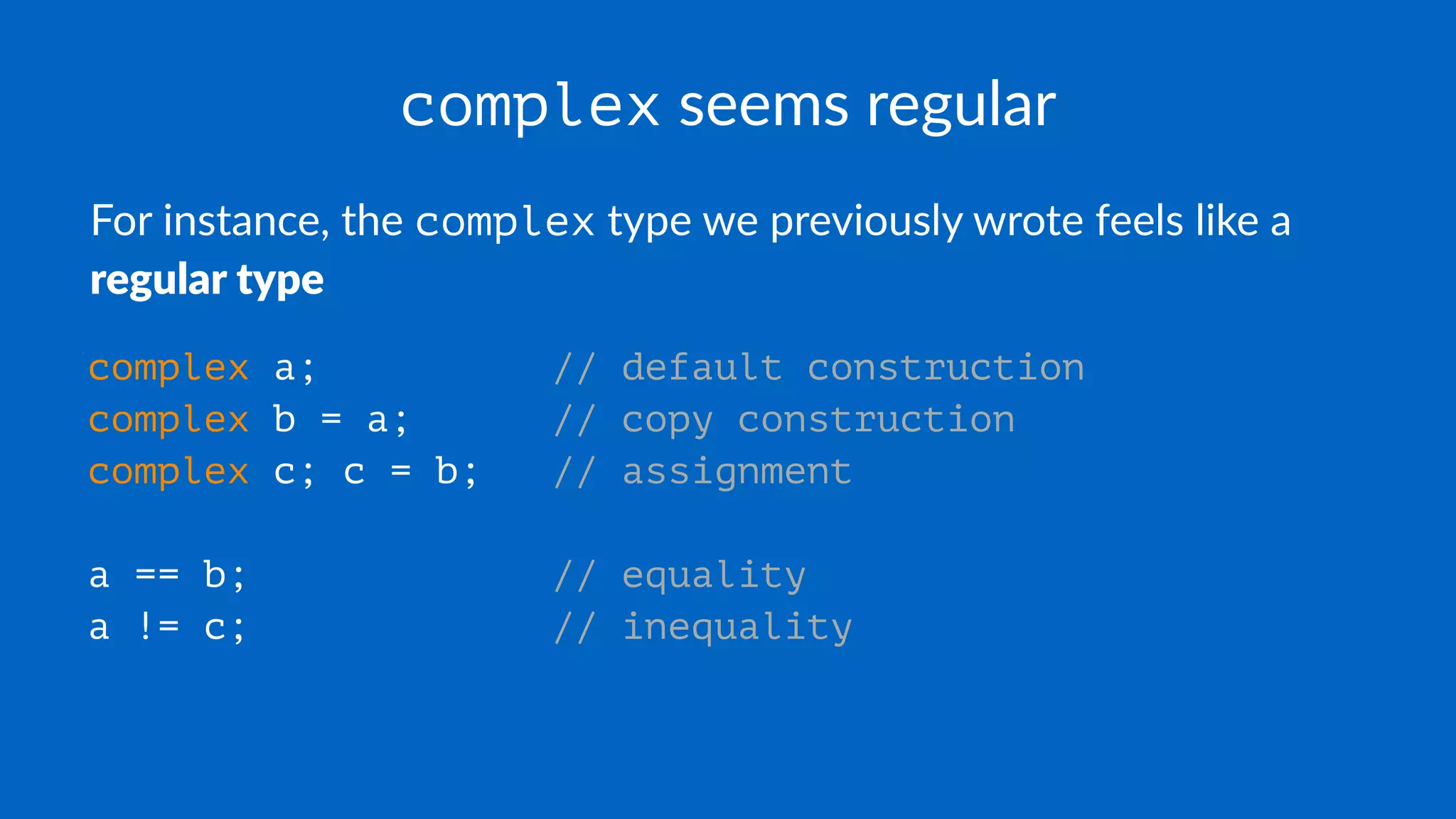

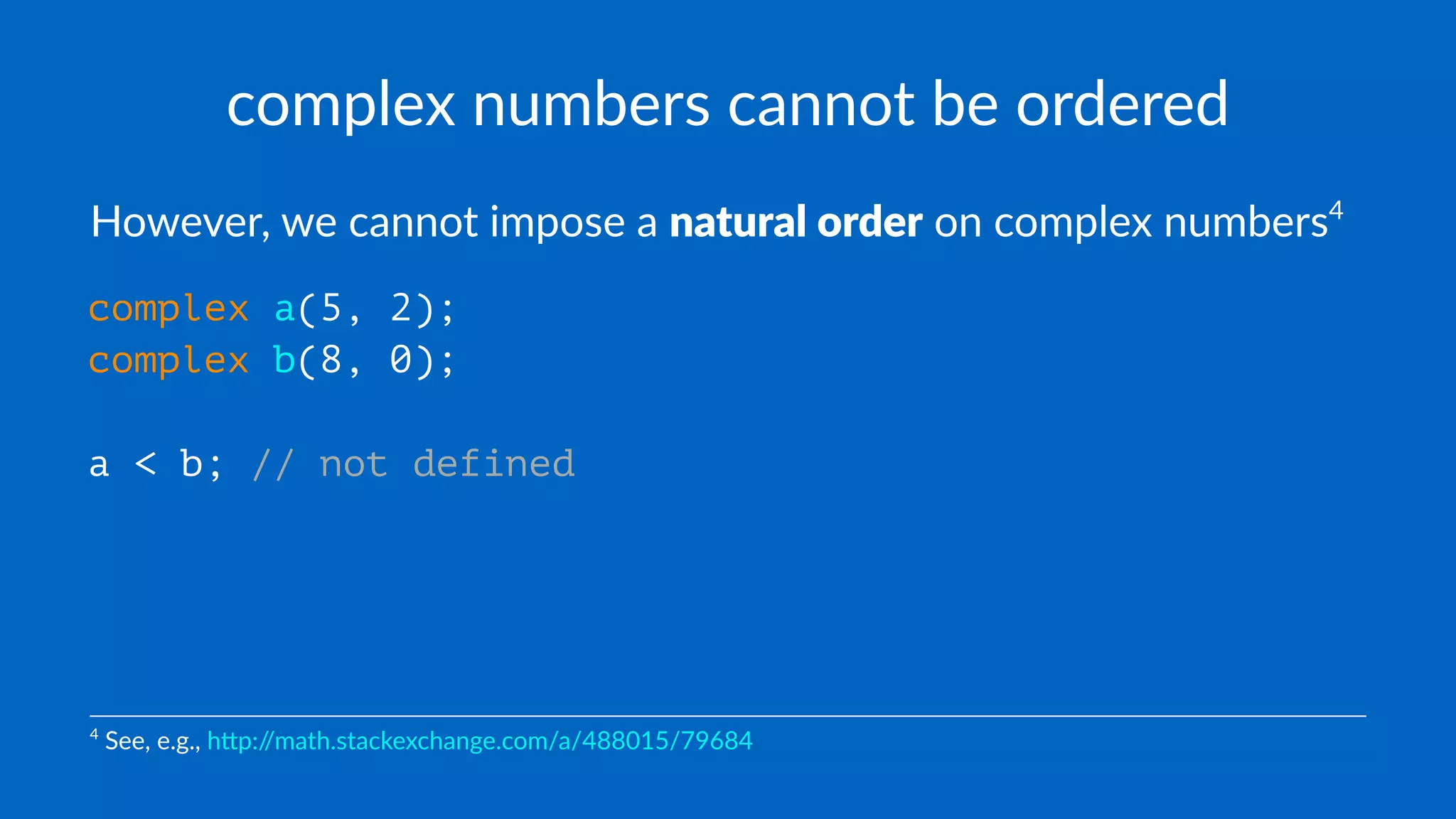

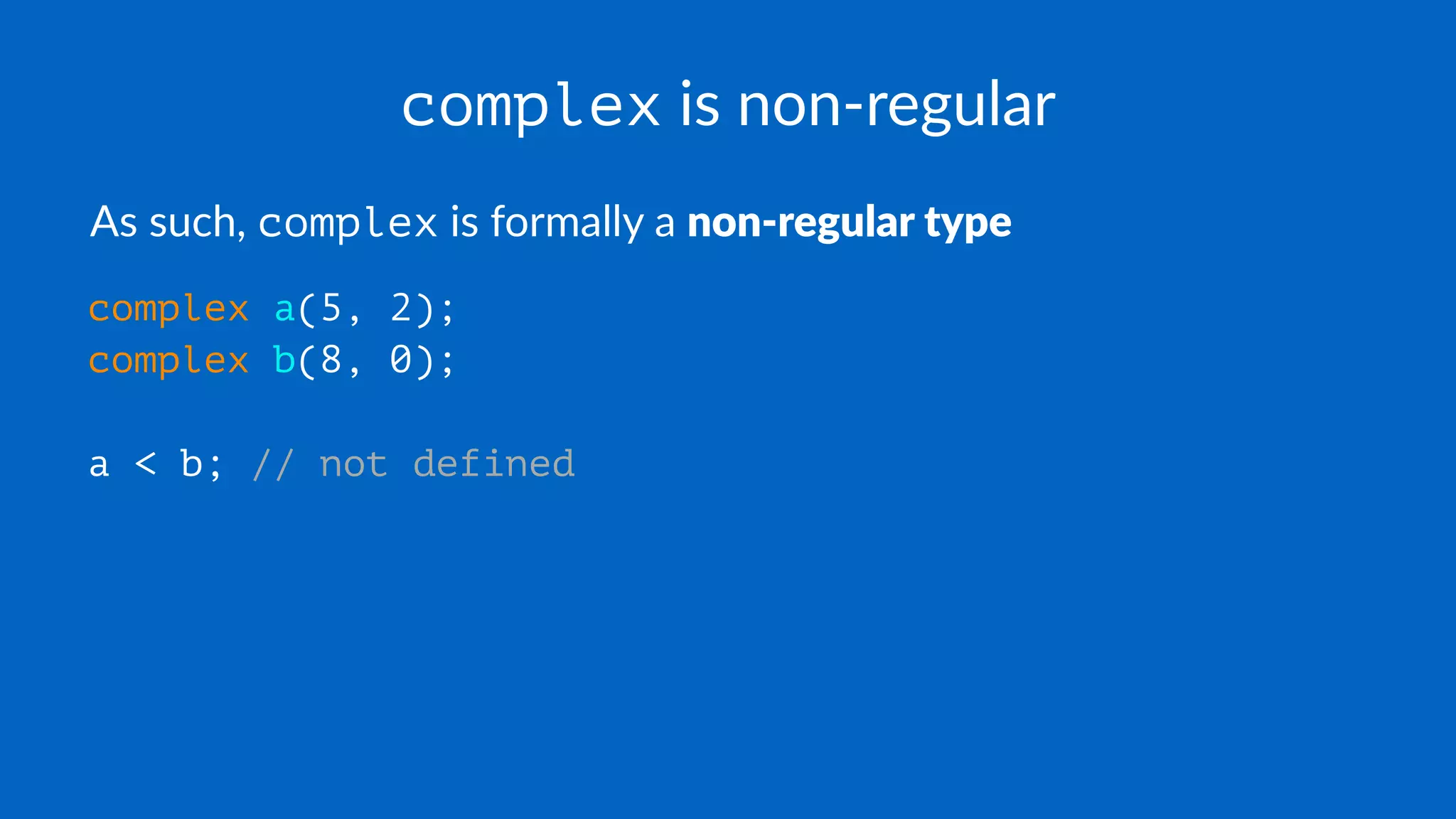

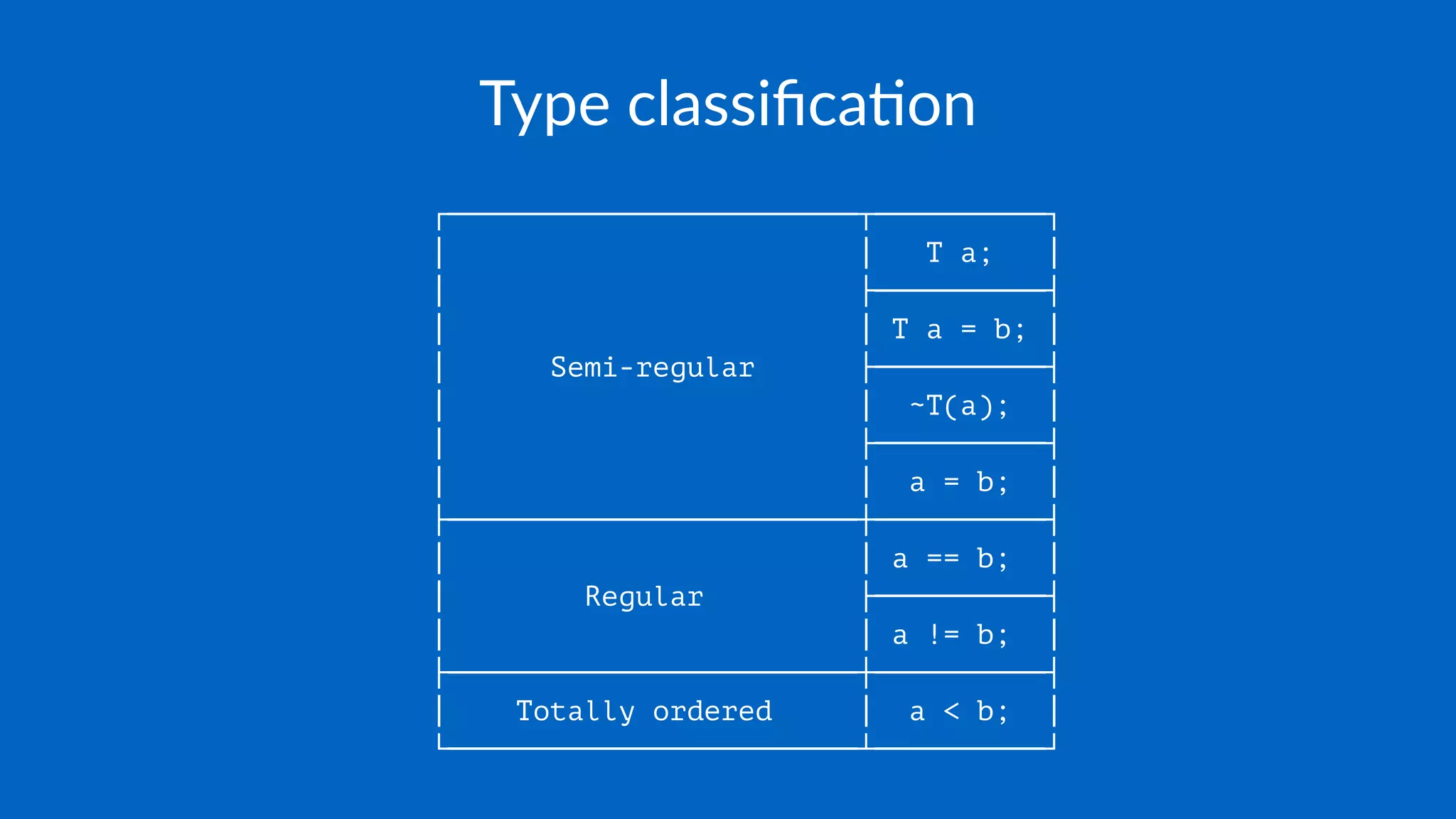

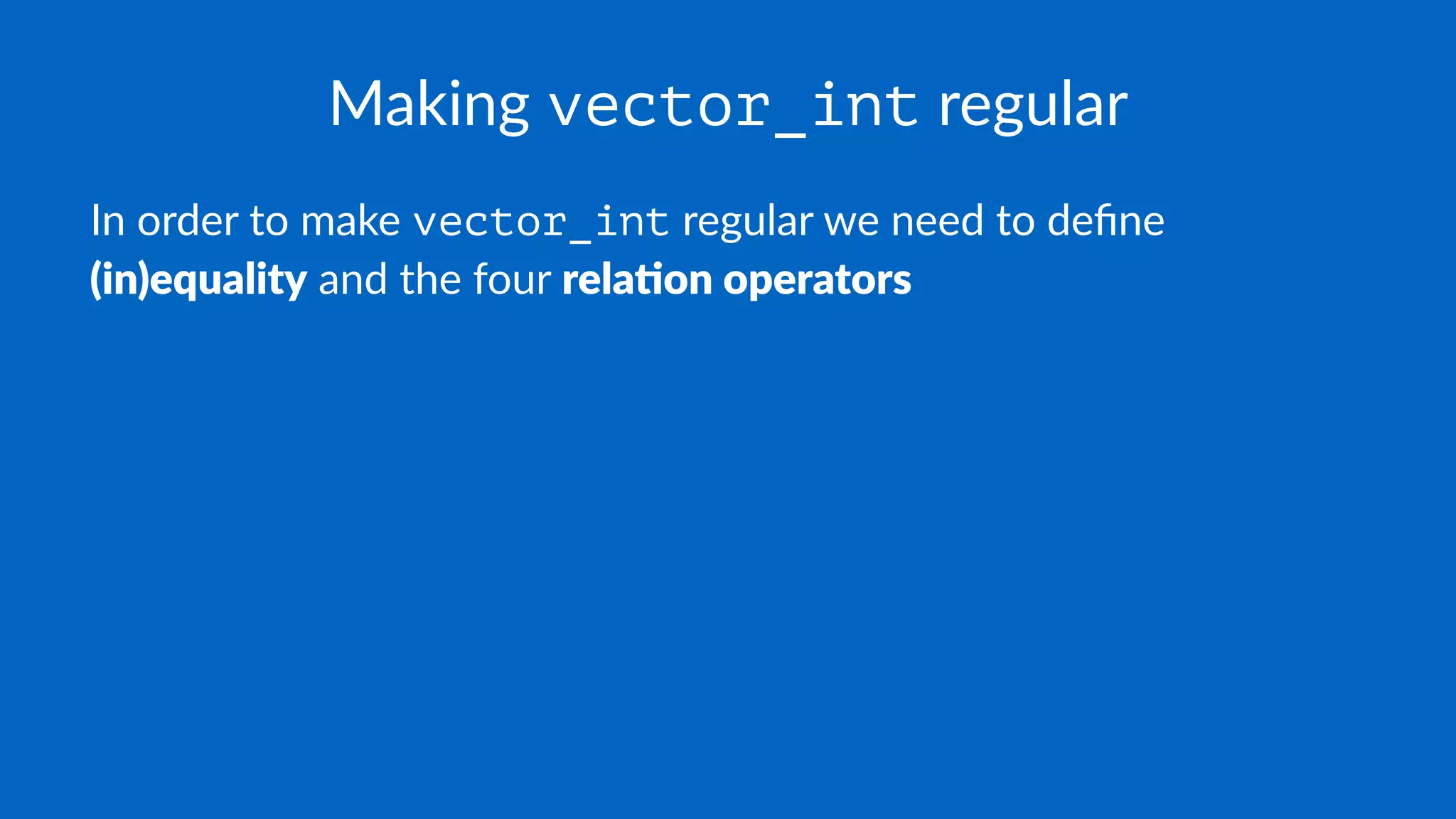

The document discusses the characteristics of regular types in C++, emphasizing their similarity to built-in types in terms of operations like assignment, copy construction, and equality. It explains the importance of defining user-defined types (UDTs) in a way that preserves the behaviors of standard operations while introducing fundamental operations consistent across built-in types. Additionally, the text highlights the need for strict and transitive definitions of ordering and equality in UDTs.

![vector_int

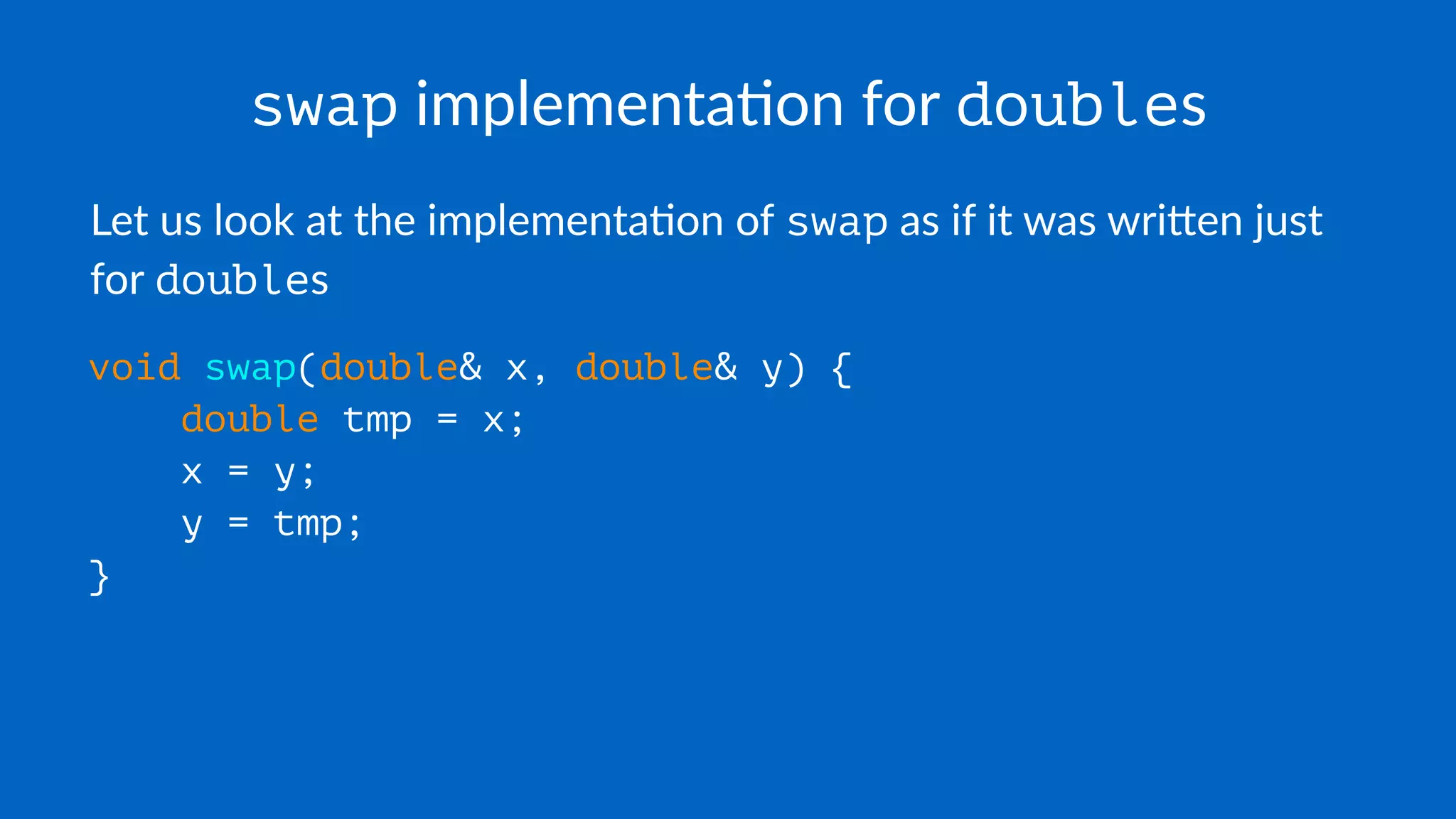

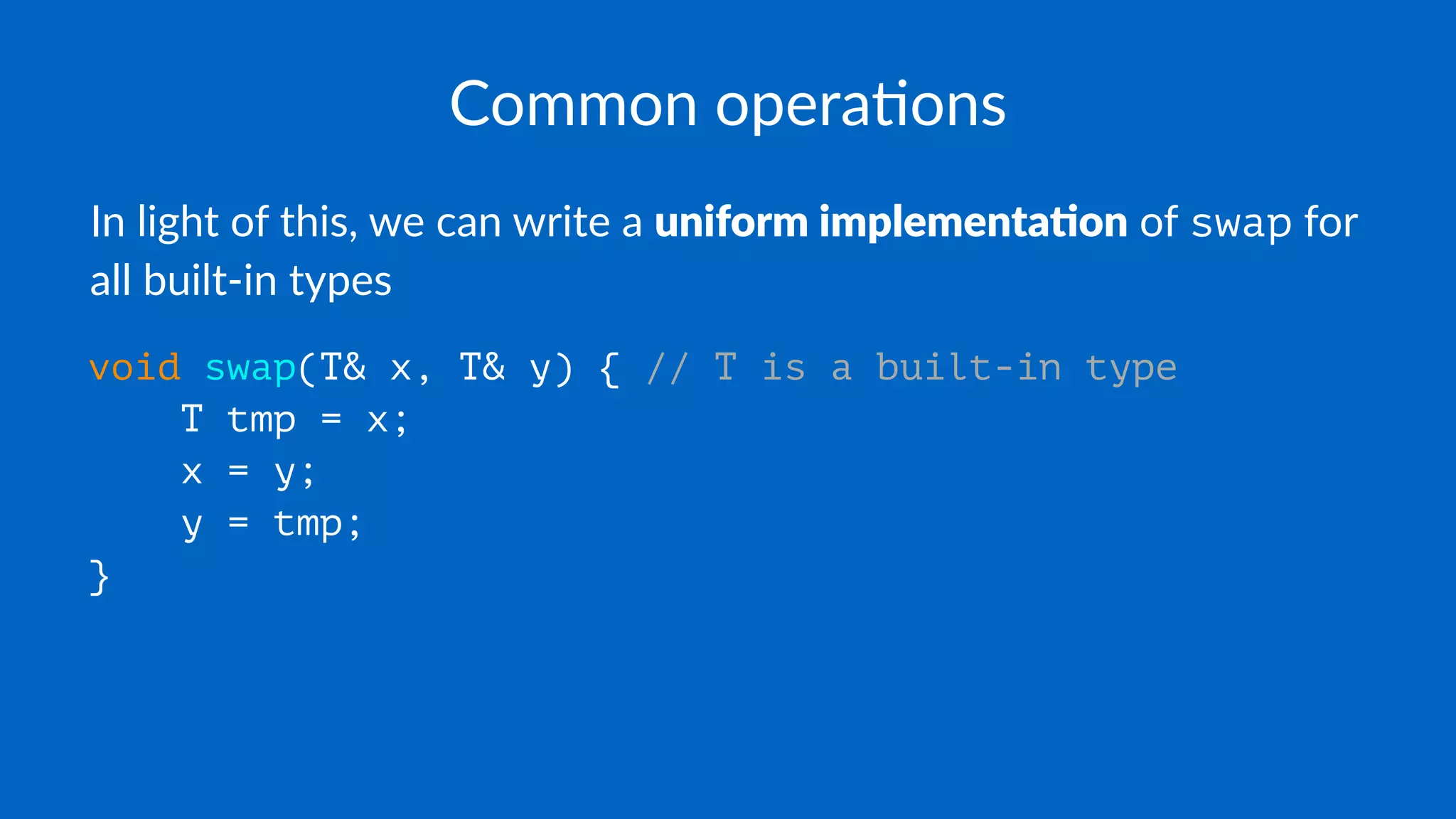

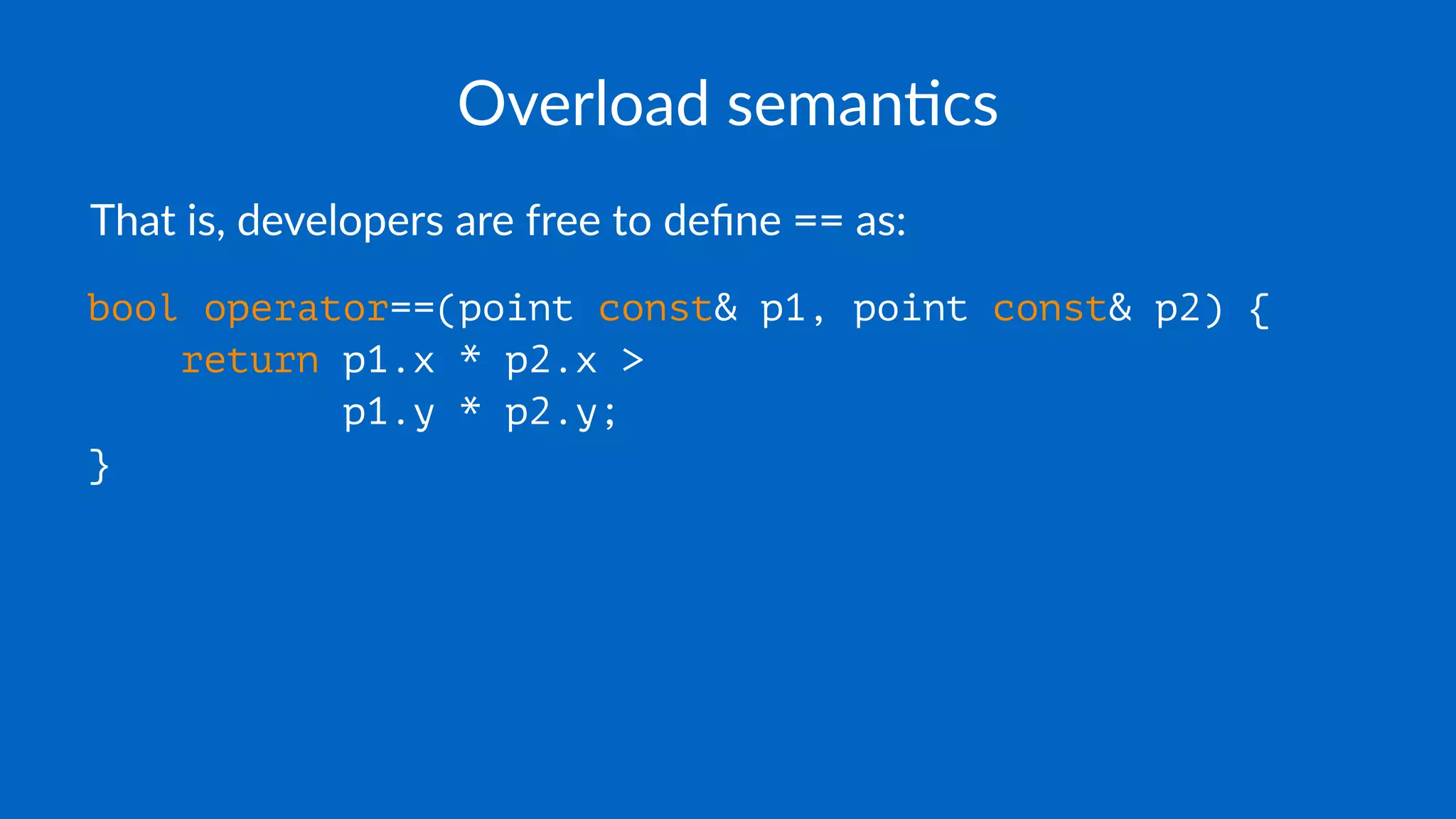

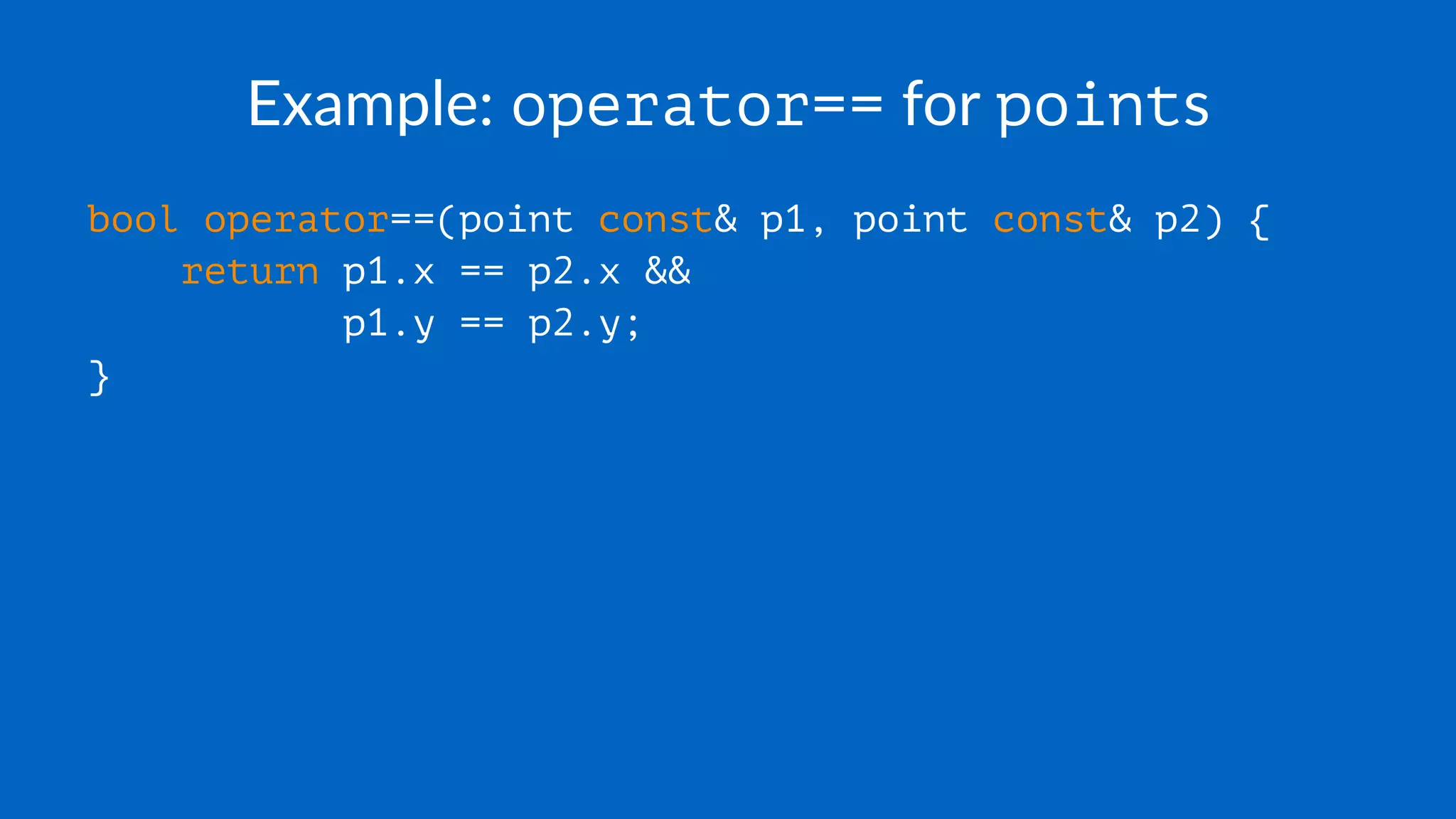

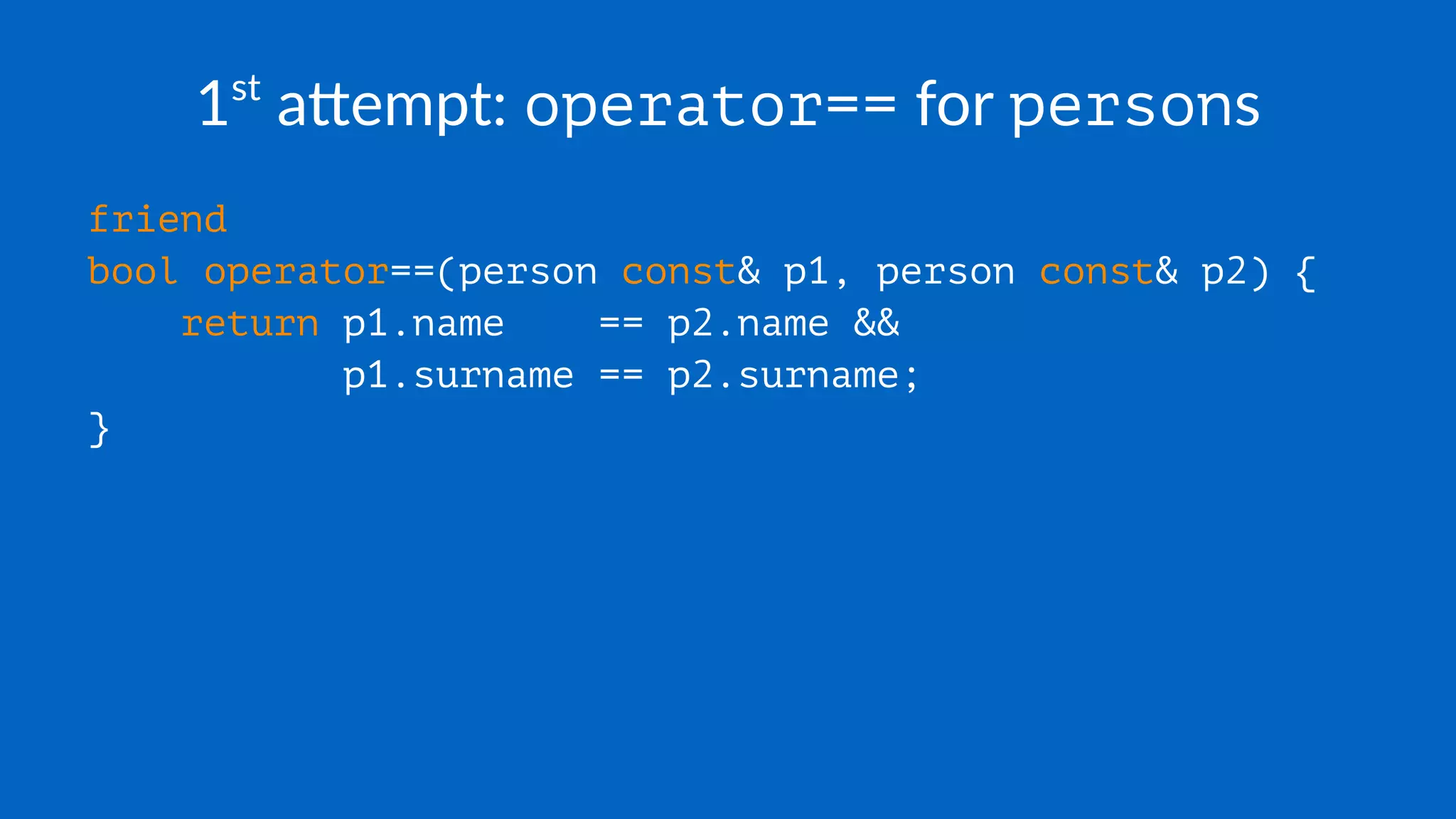

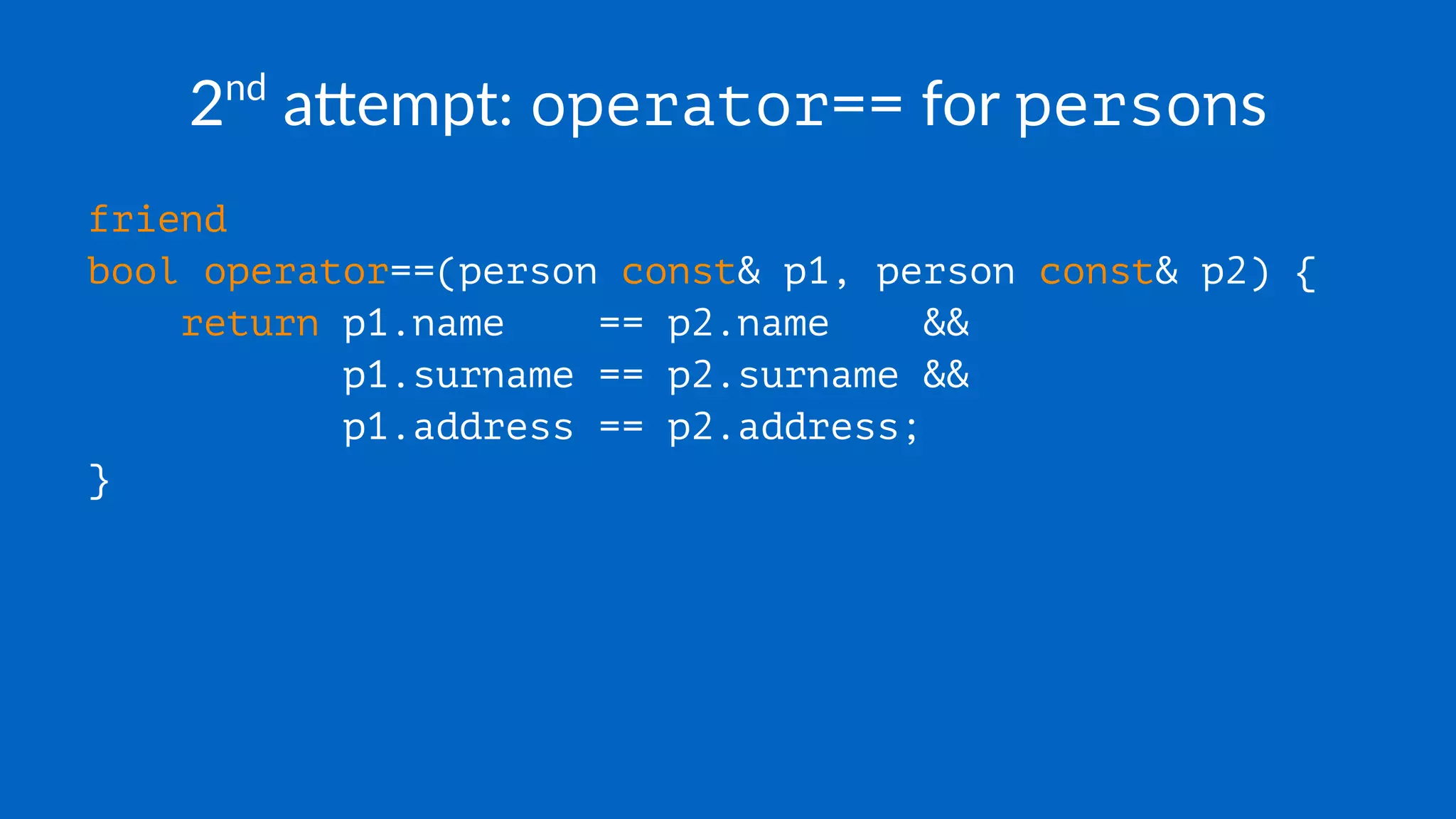

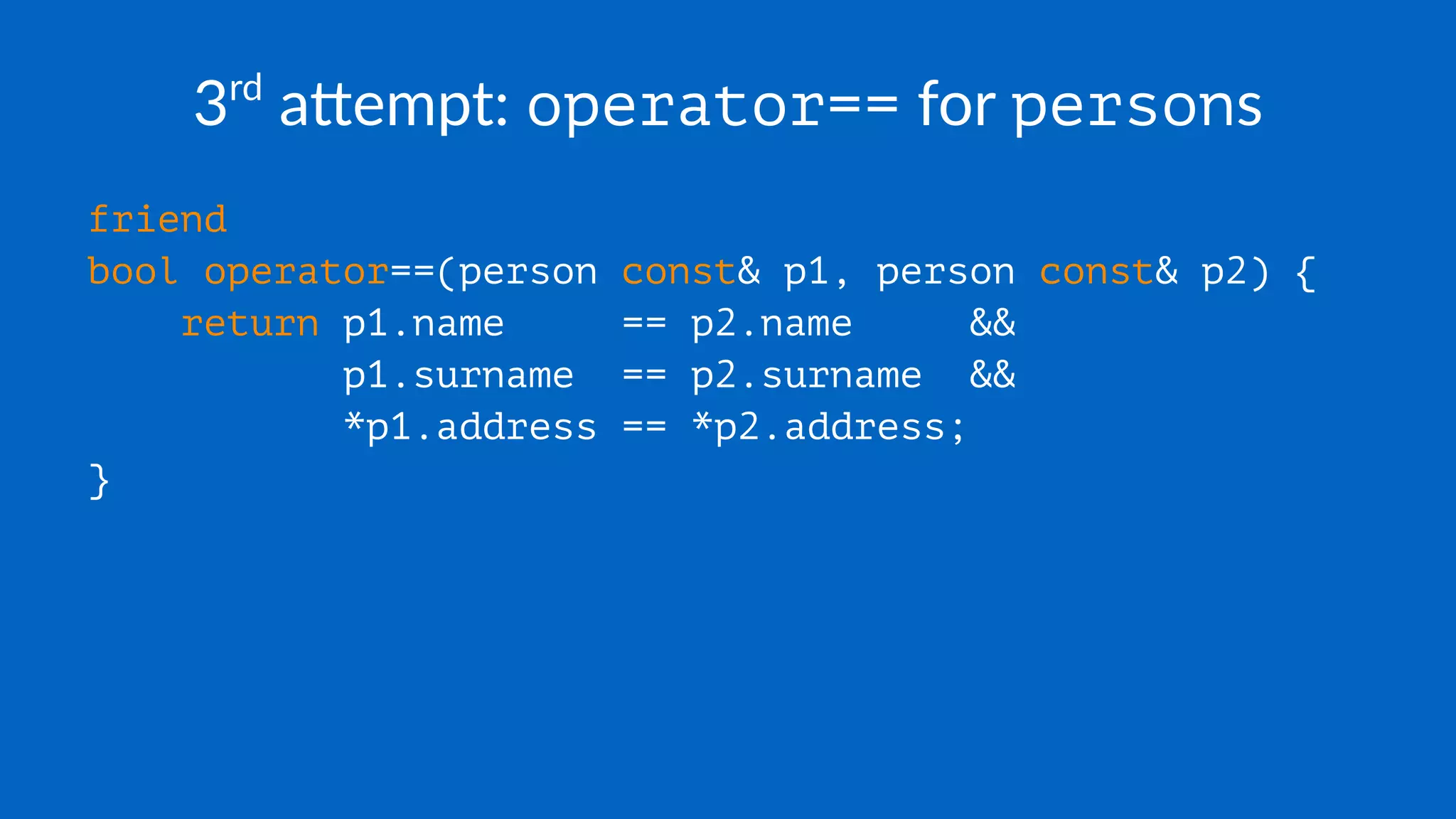

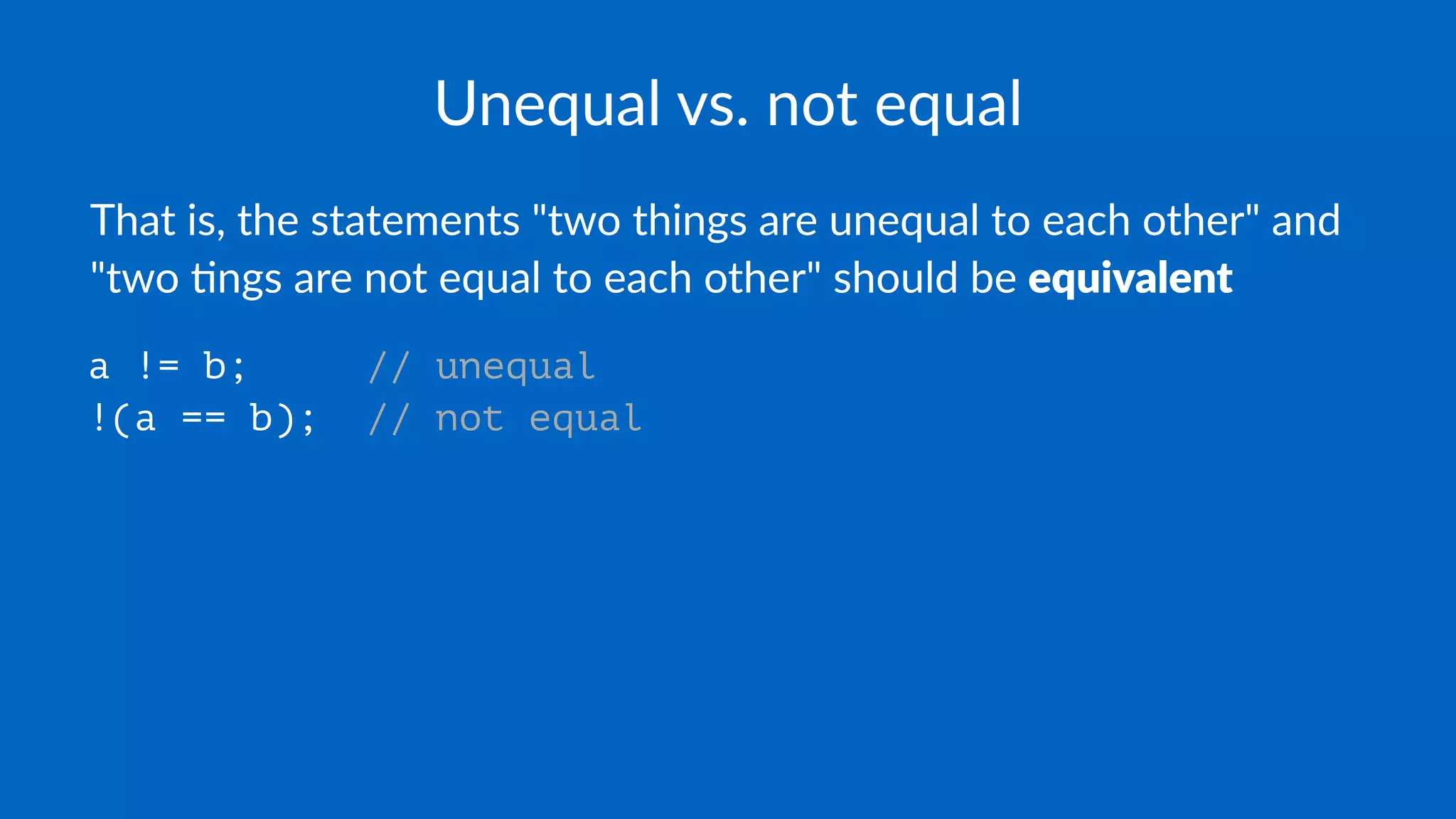

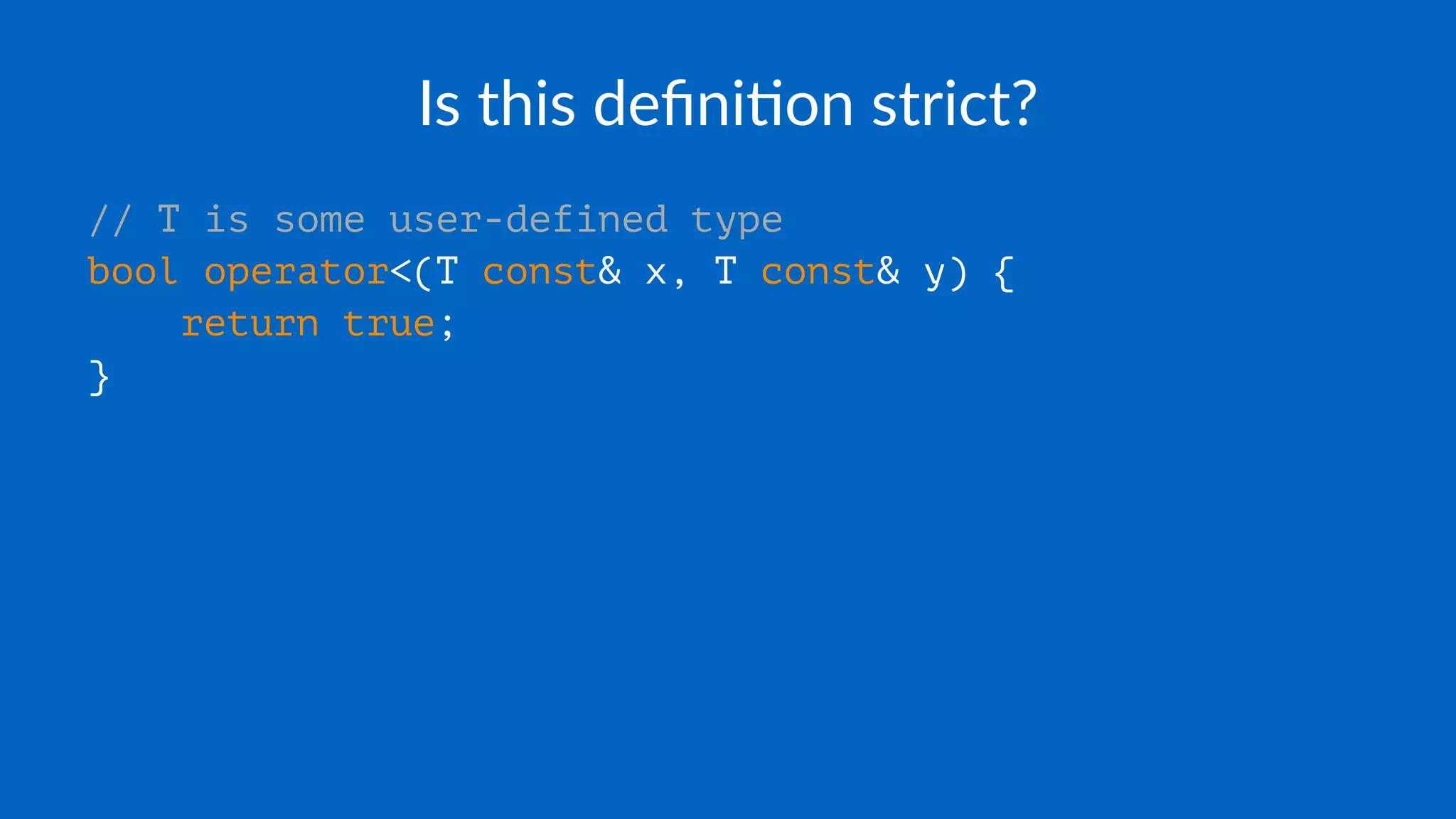

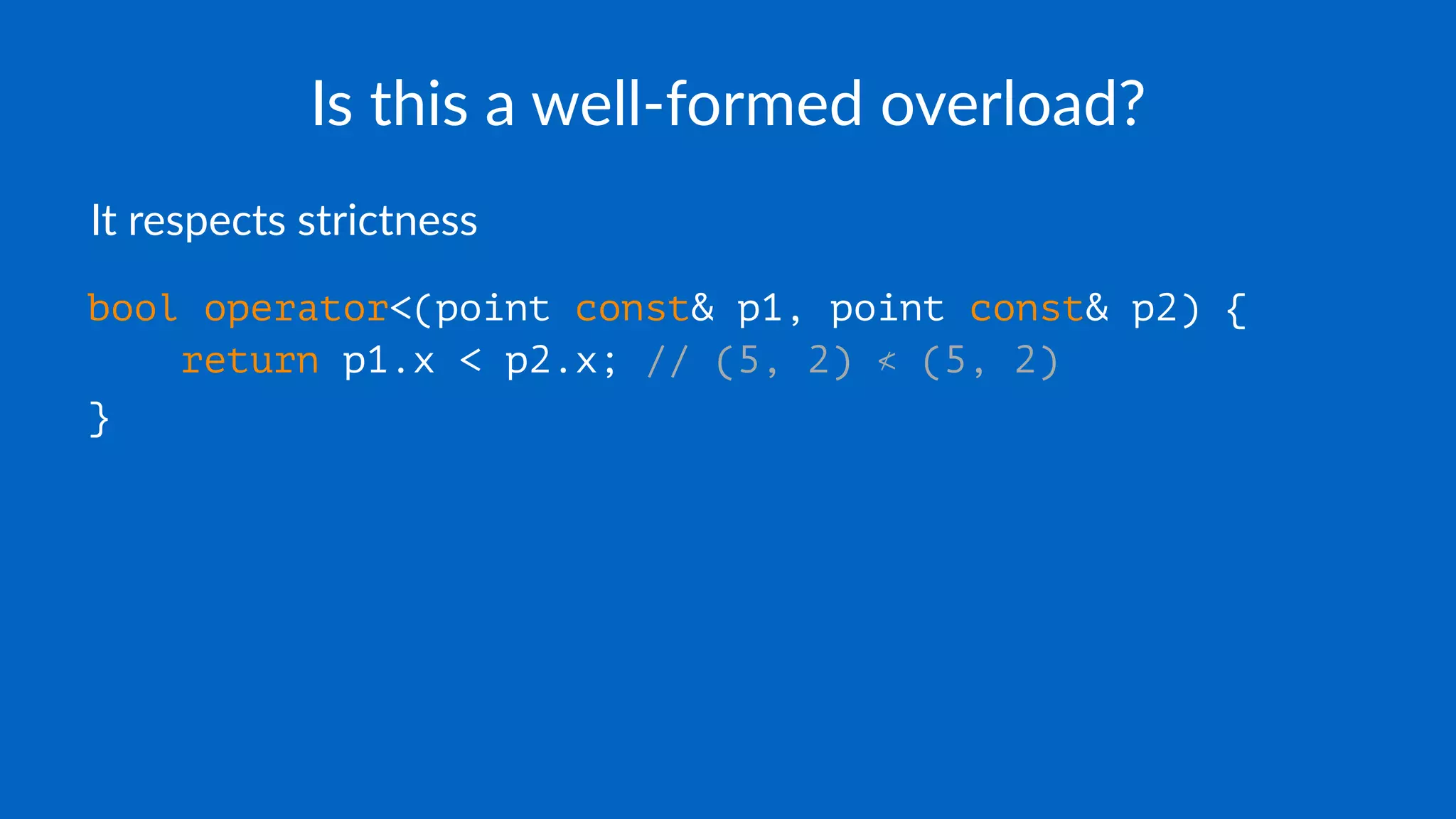

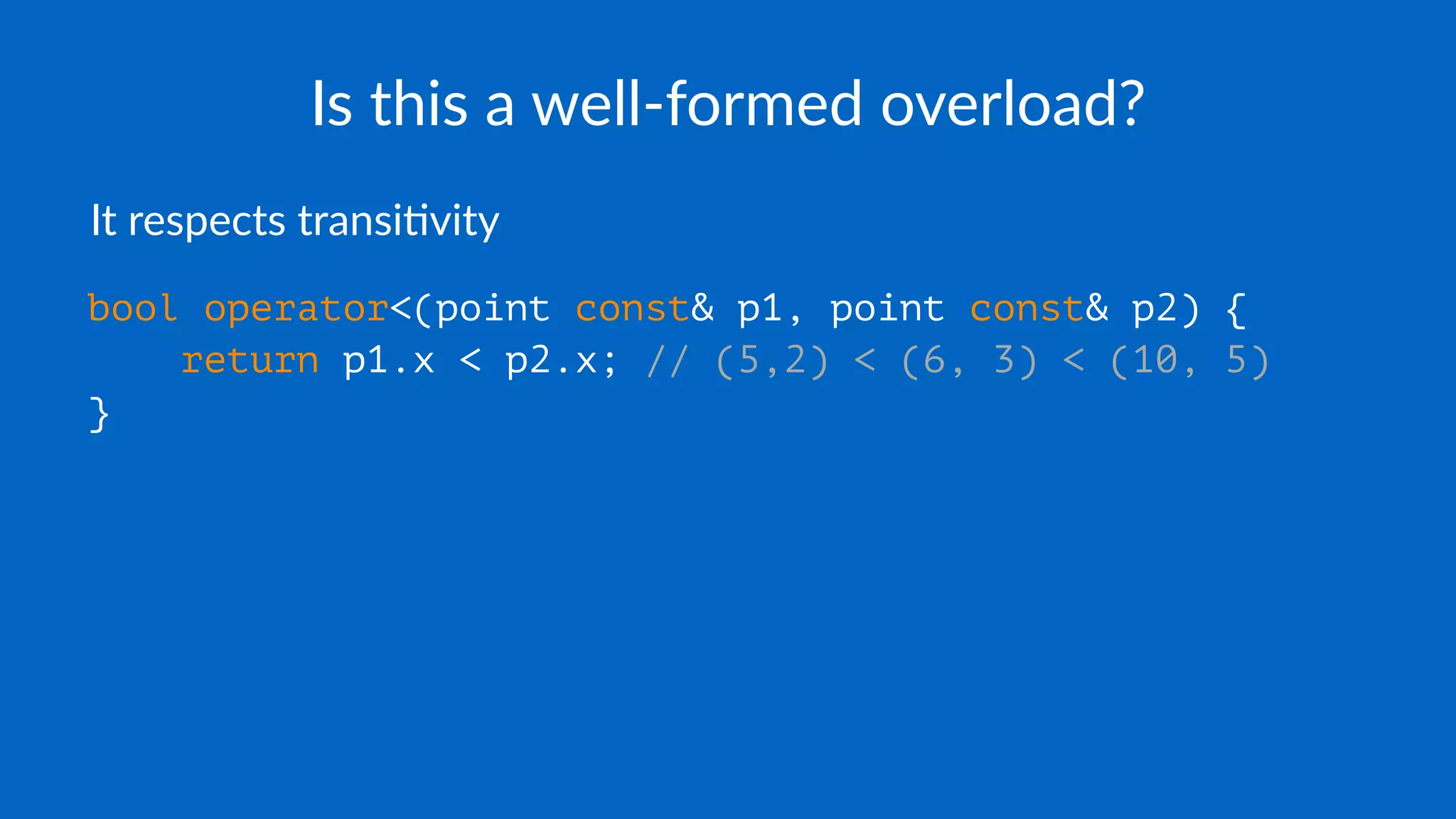

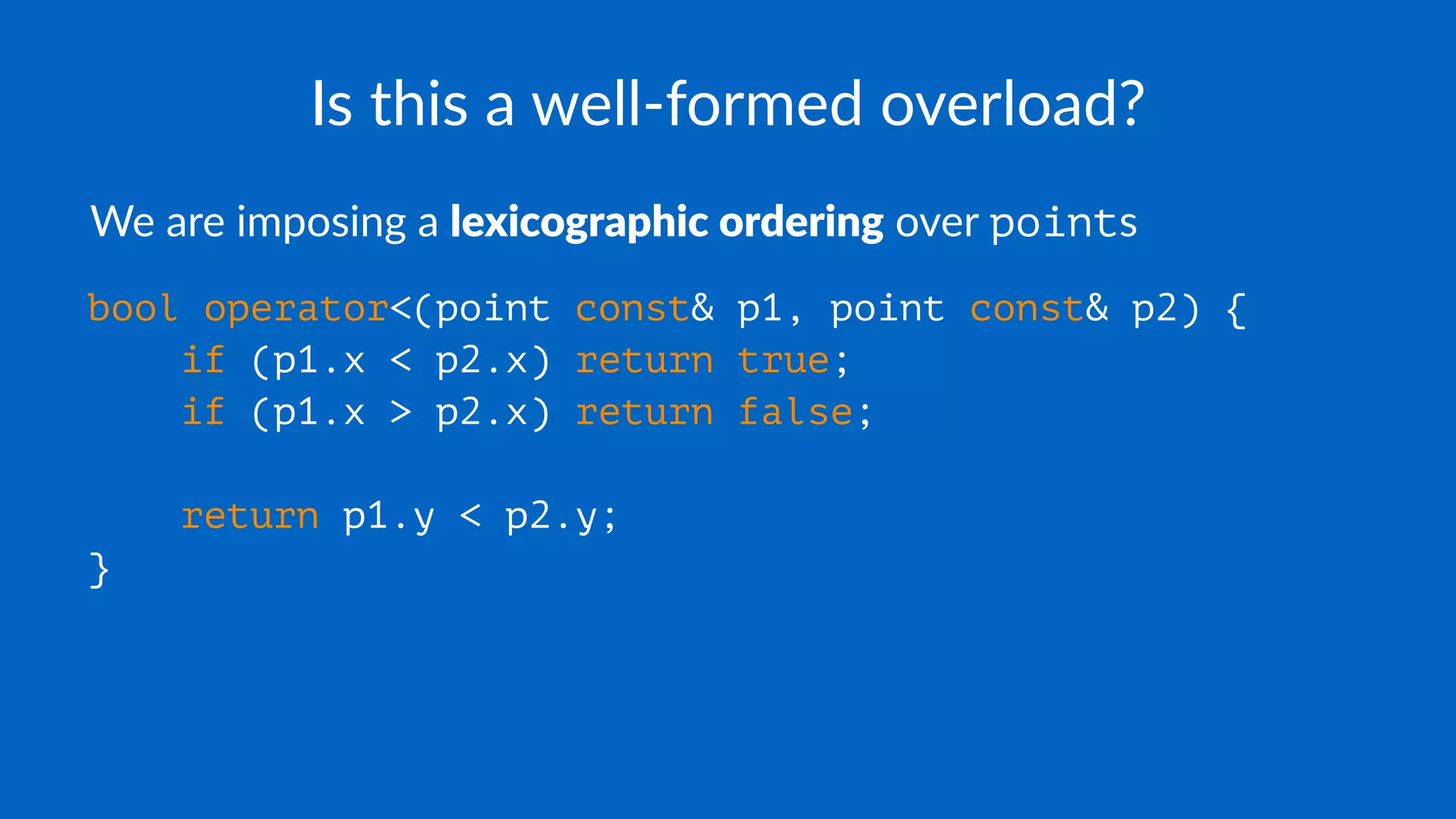

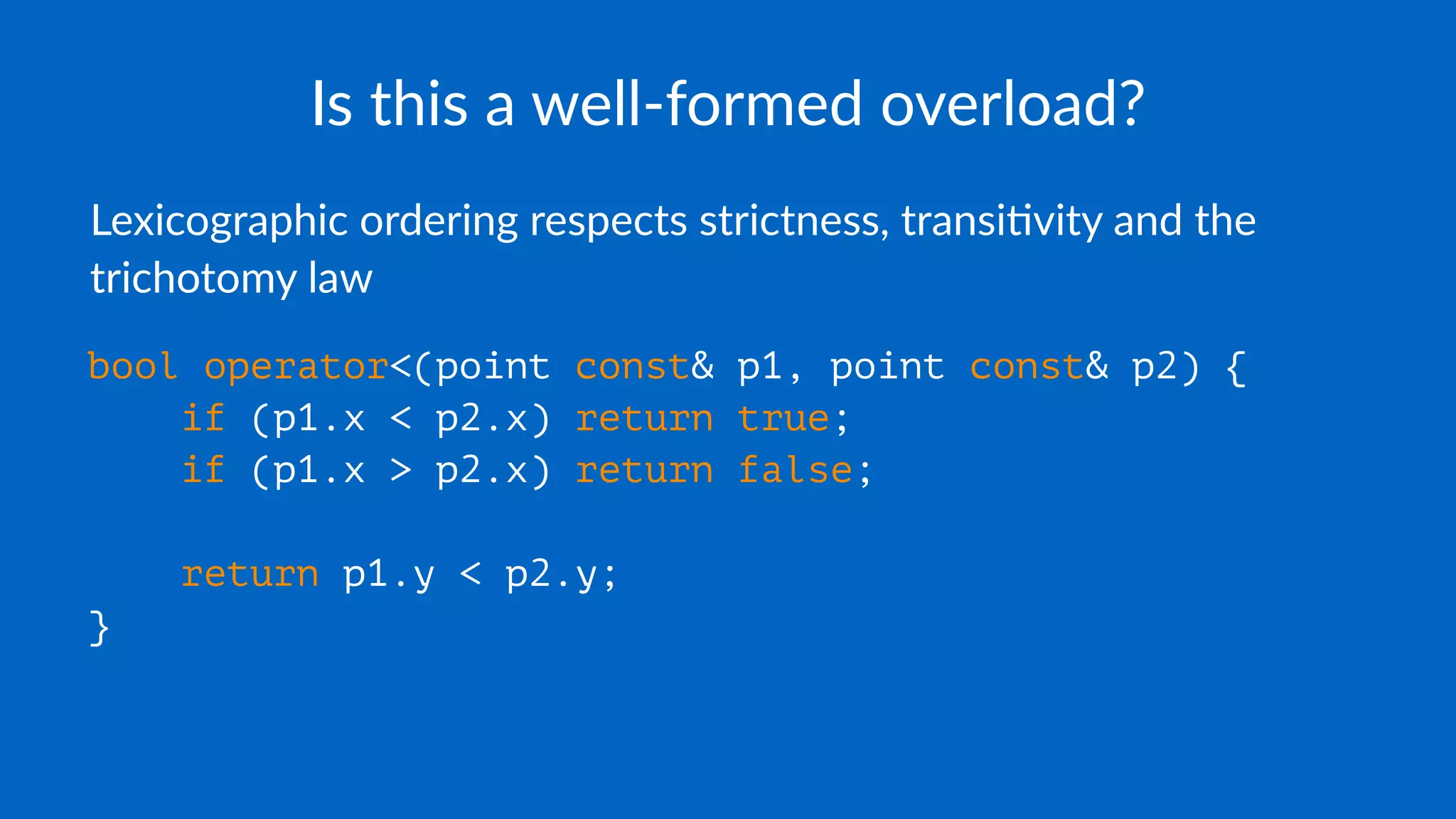

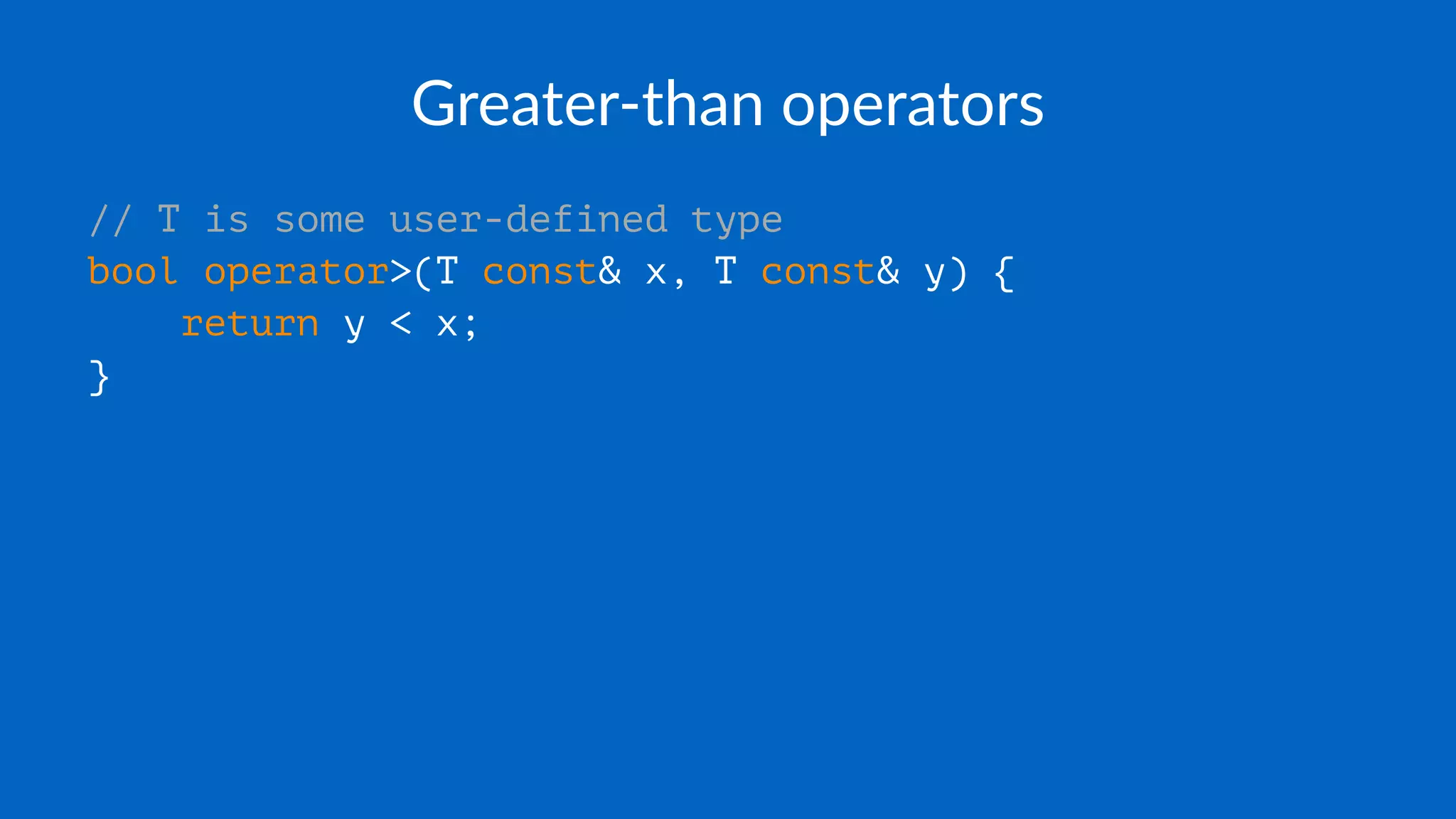

class vector_int {

public:

vector_int(): sz(0), elem(nullptr) {}

vector_int(std::size_t sz): sz(sz), elem(new int[sz]) {...}

vector_int(vector_int const& v): sz(v.sz), elem(new int[v.sz]) {...}

~vector_int() {...}

std::size_t size() const {...}

int operator[](std::size_t i) const {...}

int& operator[](std::size_t i) {...}

vector_int& operator=(vector_int const& v) {...}

private:

std::size_t sz;

int* elem;

};](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/regulartypes-160130133044/75/Regular-types-in-C-118-2048.jpg)

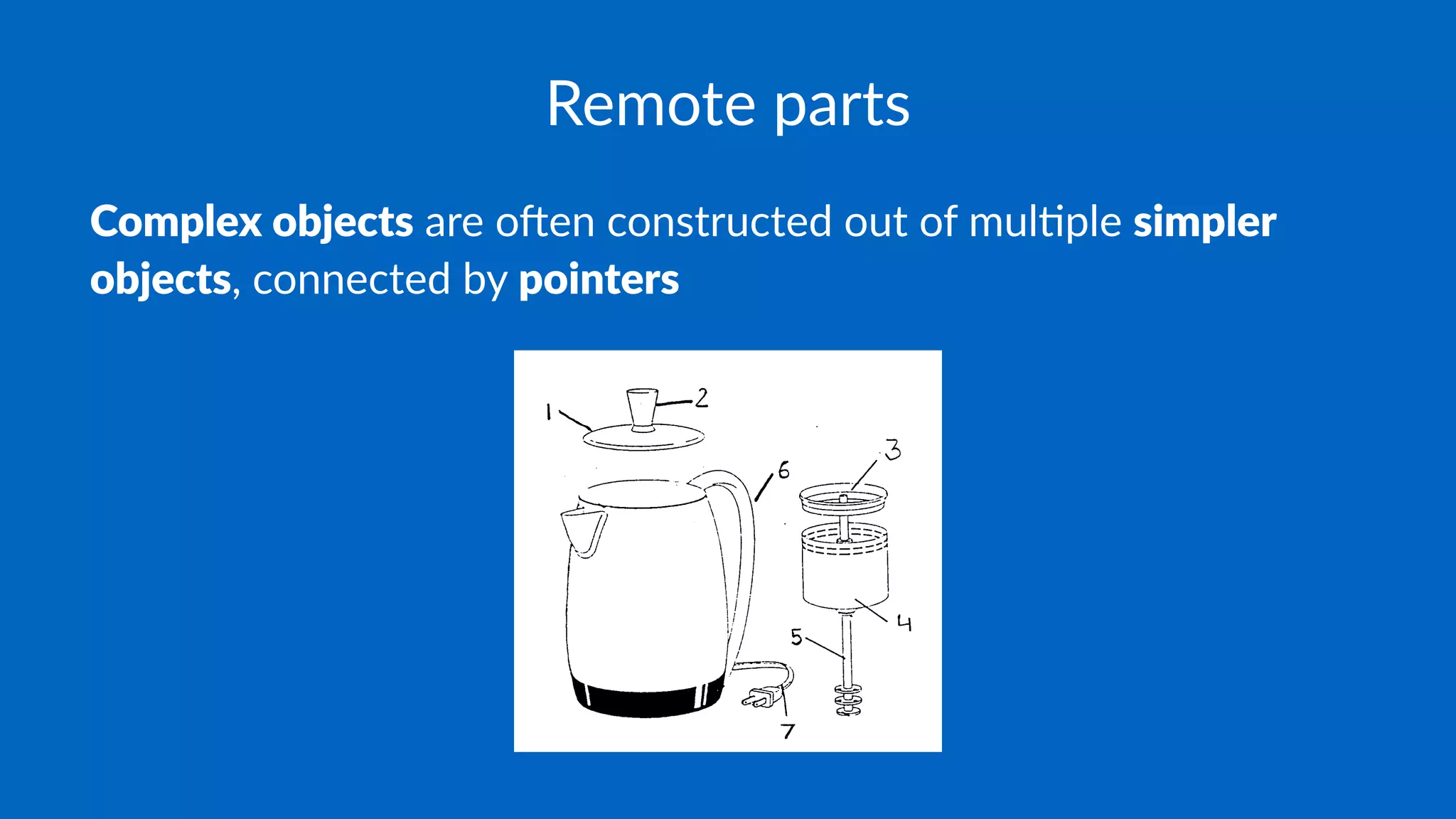

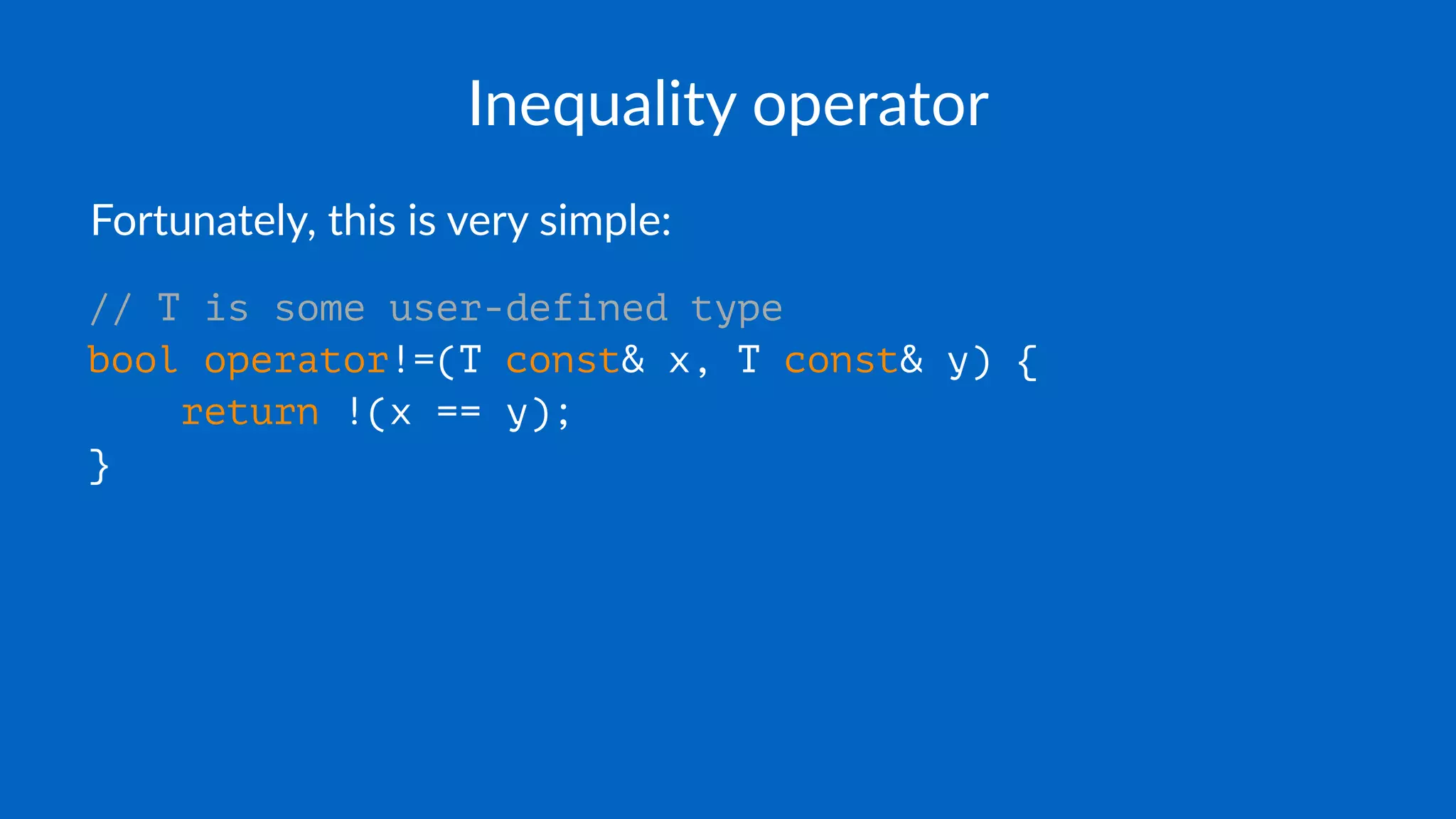

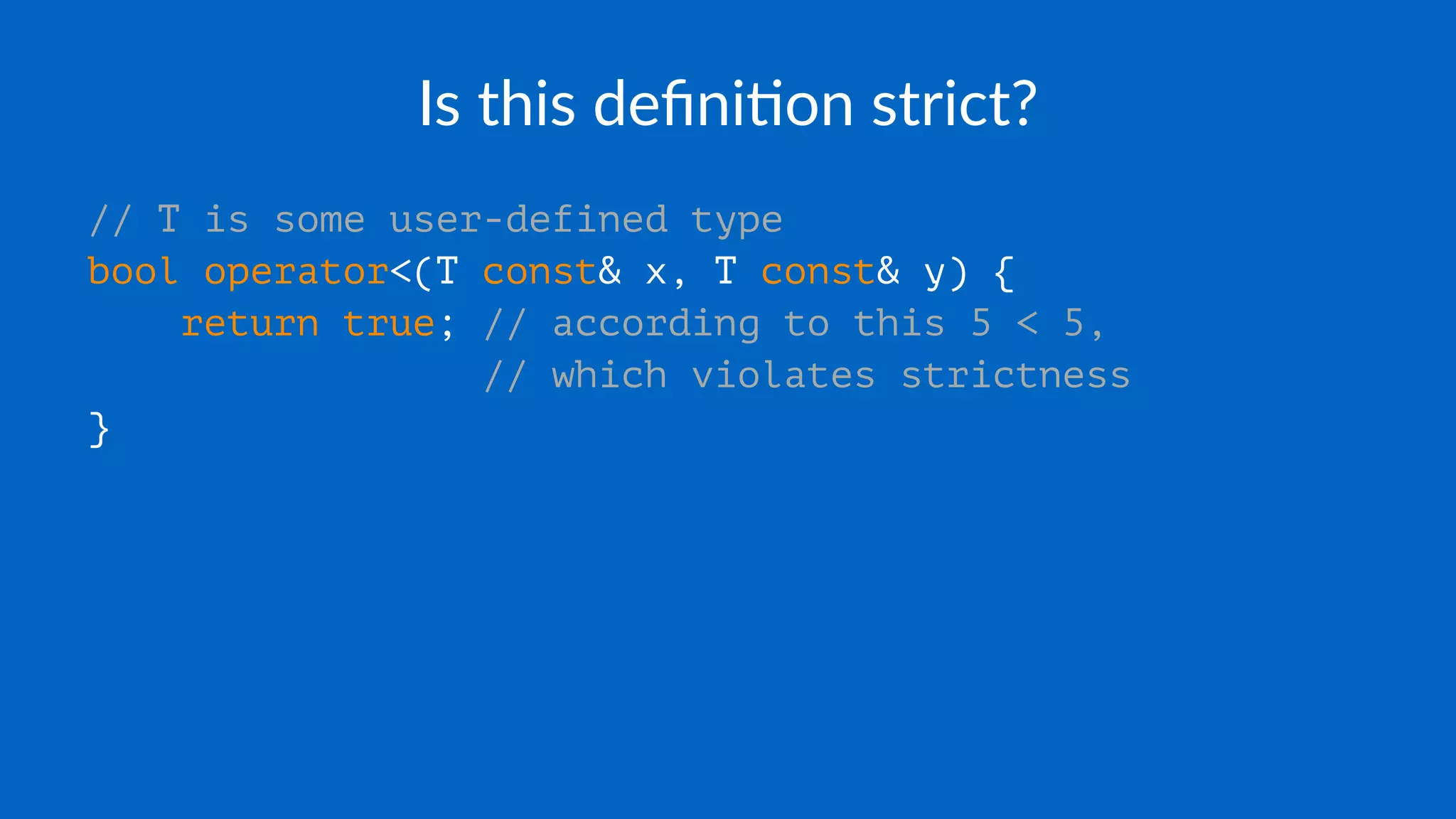

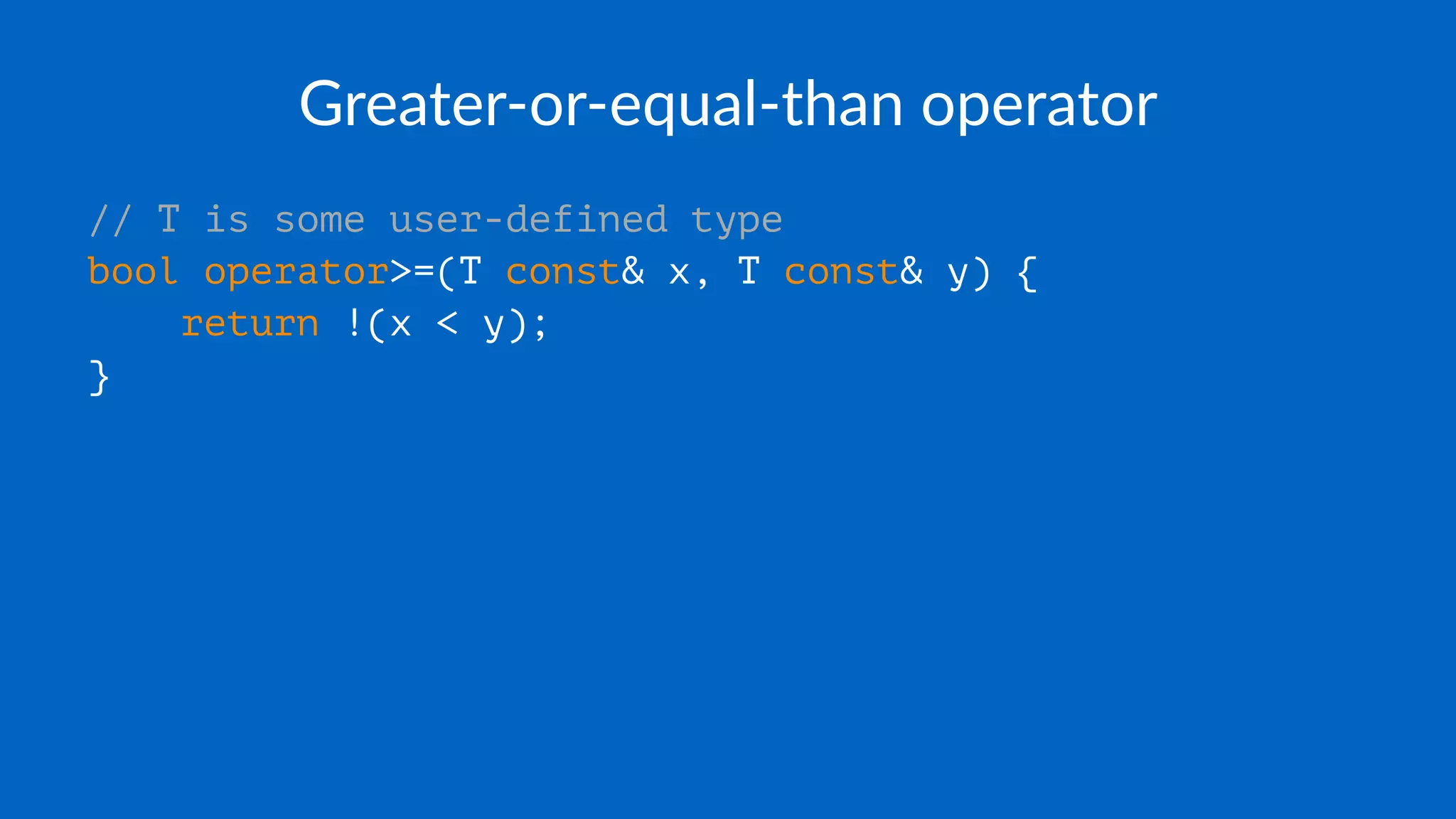

![Equality

class vector_int {

public:

...

bool operator==(vector_int const& v) const {

if (sz != v.sz) return false;

for (std::size_t i = 0; i < sz; ++i)

if (elem[i] != v.elem[i]) return false;

return true;

}

};](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/regulartypes-160130133044/75/Regular-types-in-C-120-2048.jpg)

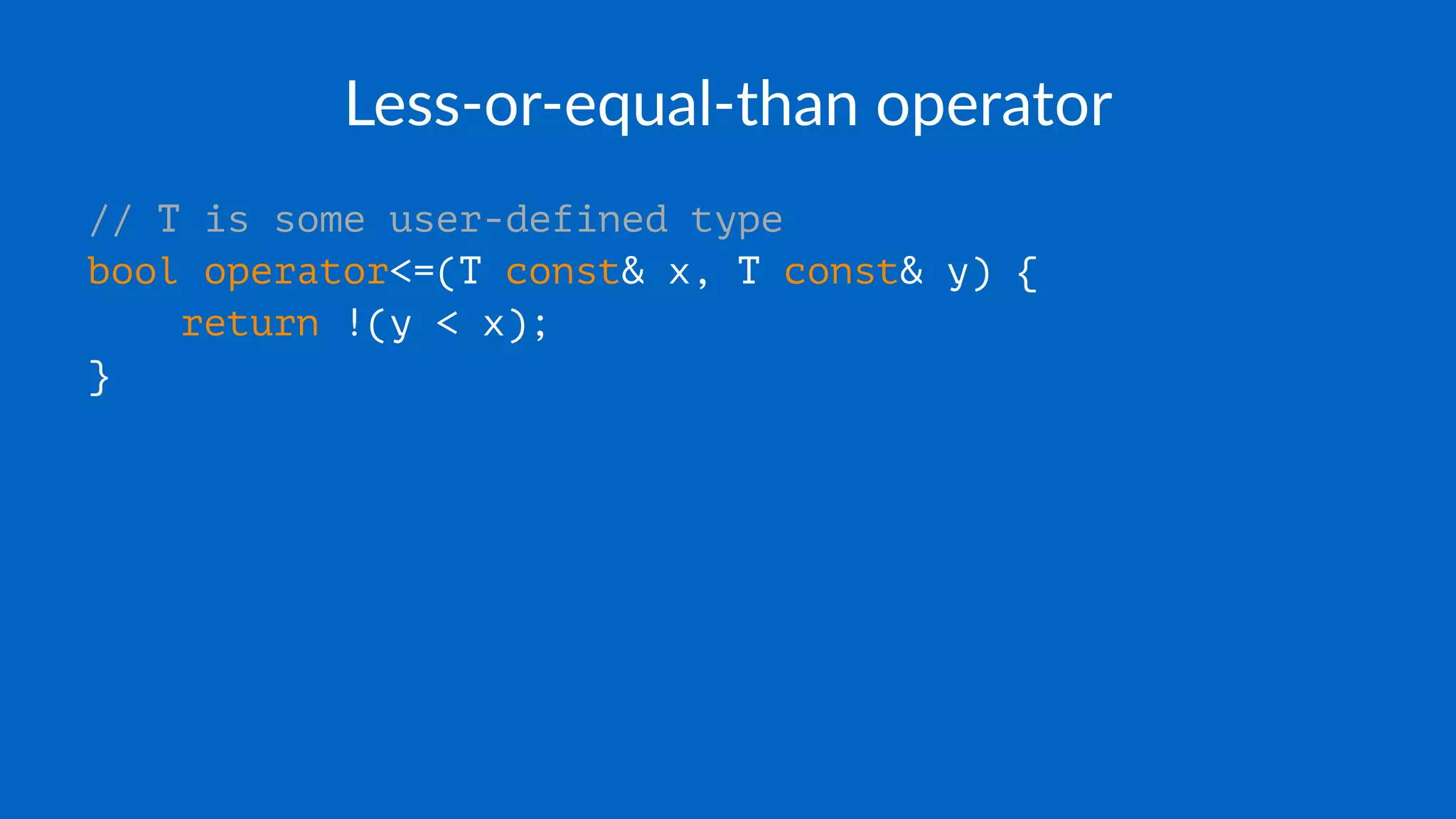

![Less-than operator

class vector_int {

public:

...

bool operator<(vector_int const& v) const {

std::size_t min_size = std::min(sz, v.sz);

std::size_t i = 0;

while (i < min_size && elem[i] == v.elem[i]) ++i;

if (i < min_size)

return elem[i] < v.elem[i];

else

return sz < v.sz;

}

};](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/regulartypes-160130133044/75/Regular-types-in-C-121-2048.jpg)