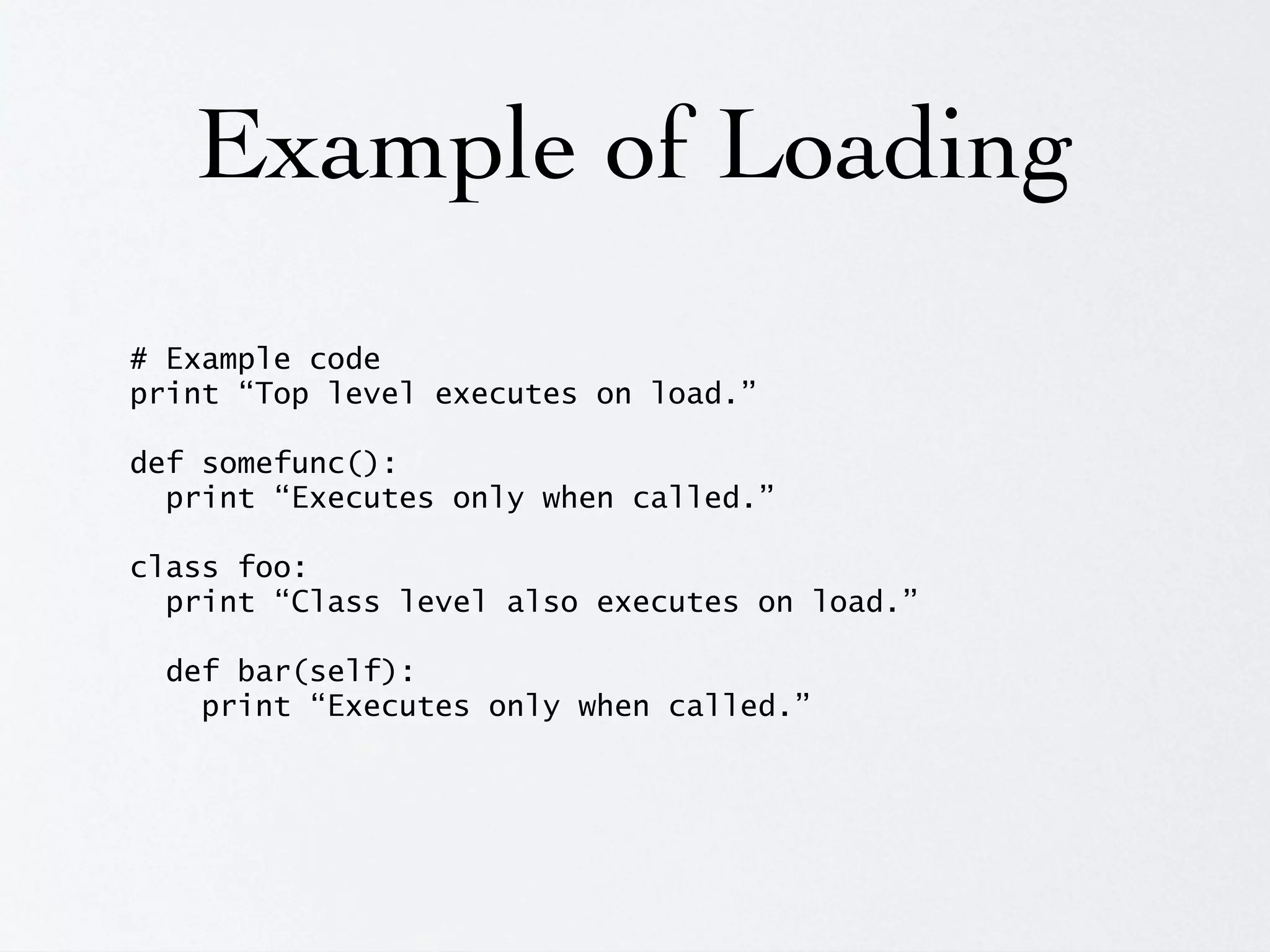

The document explores Python's dynamic nature, detailing how it supports scaling from simple scripts to complex applications. It describes Python's interpreted and compiled aspects, object-oriented features, namespaces, operator overloading, and the evolution of types and classes, particularly highlighting changes in version 2.2. Additionally, it discusses the implications of these features on code scalability, maintenance, and the development of frameworks like Zope.

![Controlling Attribute

Access

• An object can take control of the way its

attributes are accessed.

• The __getitem__ function for list or

dictionary access. Example: object[‘foo’]

• The __getattr__ function for named

access. Example: using object.foo will call

object.__getattr__(‘foo’)

• __setitem__ and __setattr__ for editing.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pythonsdynamicnature-roughslides-140305101303-phpapp01/75/Python-s-dynamic-nature-rough-slides-November-2004-8-2048.jpg)