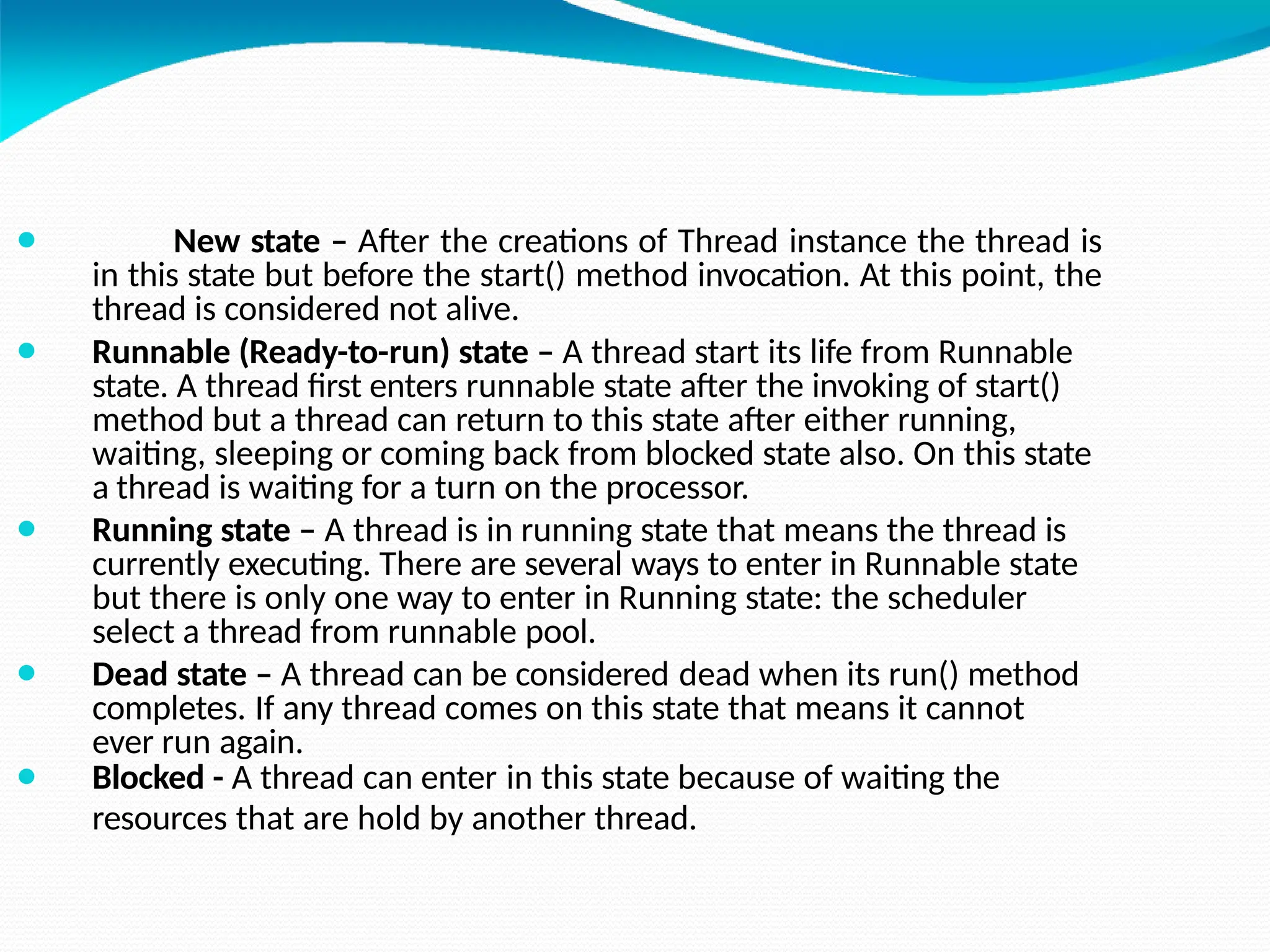

The document provides an overview of exception handling in Java, detailing concepts such as the creation, catching, and throwing of exceptions, as well as the syntax for try, catch, and finally blocks. It discusses the differentiation between checked and unchecked exceptions, the importance of grouping exceptions, and the use of user-defined exceptions. Additionally, the document touches on the benefits of exception handling, the lifecycle of threads, and the differences between multi-threading and multi-tasking.

![Catching Exceptions:

The try-catch Statements

class DivByZero {

public static void main(String args[])

{ try {

System.out.println(3/0);

System.out.println(“Please print

me.”);

} catch (ArithmeticException exc) {

//Division by zero is an

ArithmeticException

System.out.println(exc);

}

System.out.println(“After

exception.”);

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javaunit3-250119180718-20ae97d7/75/PACKAGES-INTERFACES-AND-EXCEPTION-HANDLING-16-2048.jpg)

![Catching Exceptions:

Multiple catch

class MultipleCatch {

public static void main(String args[])

{ try {

int den = Integer.parseInt(args[0]);

System.out.println(3/den);

} catch (ArithmeticException exc)

{ System.out.println(“Divisor was

0.”);

} catch

(ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException

exc2) {

System.out.println(“Missing

argument.”);

}

System.out.println(“After](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javaunit3-250119180718-20ae97d7/75/PACKAGES-INTERFACES-AND-EXCEPTION-HANDLING-17-2048.jpg)

![Catching Exceptions:

Nested try's

class NestedTryDemo {

public static void main(String args[]){

try {

int a = Integer.parseInt(args[0]);

try {

int b = Integer.parseInt(args[1]);

System.out.println(a/b);

} catch (ArithmeticException e) {

System.out.println(“Div by zero error!");

} } catch (ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException) {

System.out.println(“Need 2 parameters!");

} } }](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javaunit3-250119180718-20ae97d7/75/PACKAGES-INTERFACES-AND-EXCEPTION-HANDLING-18-2048.jpg)

![Catching Exceptions:

Nested try's with methods

class NestedTryDemo2 {

static void nestedTry(String args[]) {

try {

int a = Integer.parseInt(args[0]);

int b = Integer.parseInt(args[1]);

System.out.println(a/b);

} catch (ArithmeticException e)

{ System.out.println("Div by zero

error!");

} }

public static void main(String args[]){

try {

nestedTry(args);

} catch

(ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException e) {](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javaunit3-250119180718-20ae97d7/75/PACKAGES-INTERFACES-AND-EXCEPTION-HANDLING-19-2048.jpg)

![Example: throw 2

The main method calls demoproc within the try

block which catches and handles the

NullPointerException exception:

public static void main(String args[]) {

try

{ demoproc(

);

} catch(NullPointerException e)

{ System.out.println("Recaught: " +

e);

}

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javaunit3-250119180718-20ae97d7/75/PACKAGES-INTERFACES-AND-EXCEPTION-HANDLING-23-2048.jpg)

![Example: throws 1

⚫The throwOne method throws an exception that it does not

catch, nor declares it within the throws clause.

class ThrowsDemo {

static void throwOne()

{ System.out.println("Inside throwOne.");

throw new IllegalAccessException("demo");

}

public static void main(String args[]) {

throwOne();

}

}

⚫Therefore this program does not compile.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javaunit3-250119180718-20ae97d7/75/PACKAGES-INTERFACES-AND-EXCEPTION-HANDLING-25-2048.jpg)

![Example: throws 2

⚫Corrected program: throwOne lists exception, main catches it:

class ThrowsDemo {

static void throwOne() throws IllegalAccessException {

System.out.println("Inside throwOne.");

throw new IllegalAccessException("demo");

}

public static void main(String args[]) {

try {

throwOne();

} catch (IllegalAccessException e) {

System.out.println("Caught " + e);

} } }](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javaunit3-250119180718-20ae97d7/75/PACKAGES-INTERFACES-AND-EXCEPTION-HANDLING-26-2048.jpg)

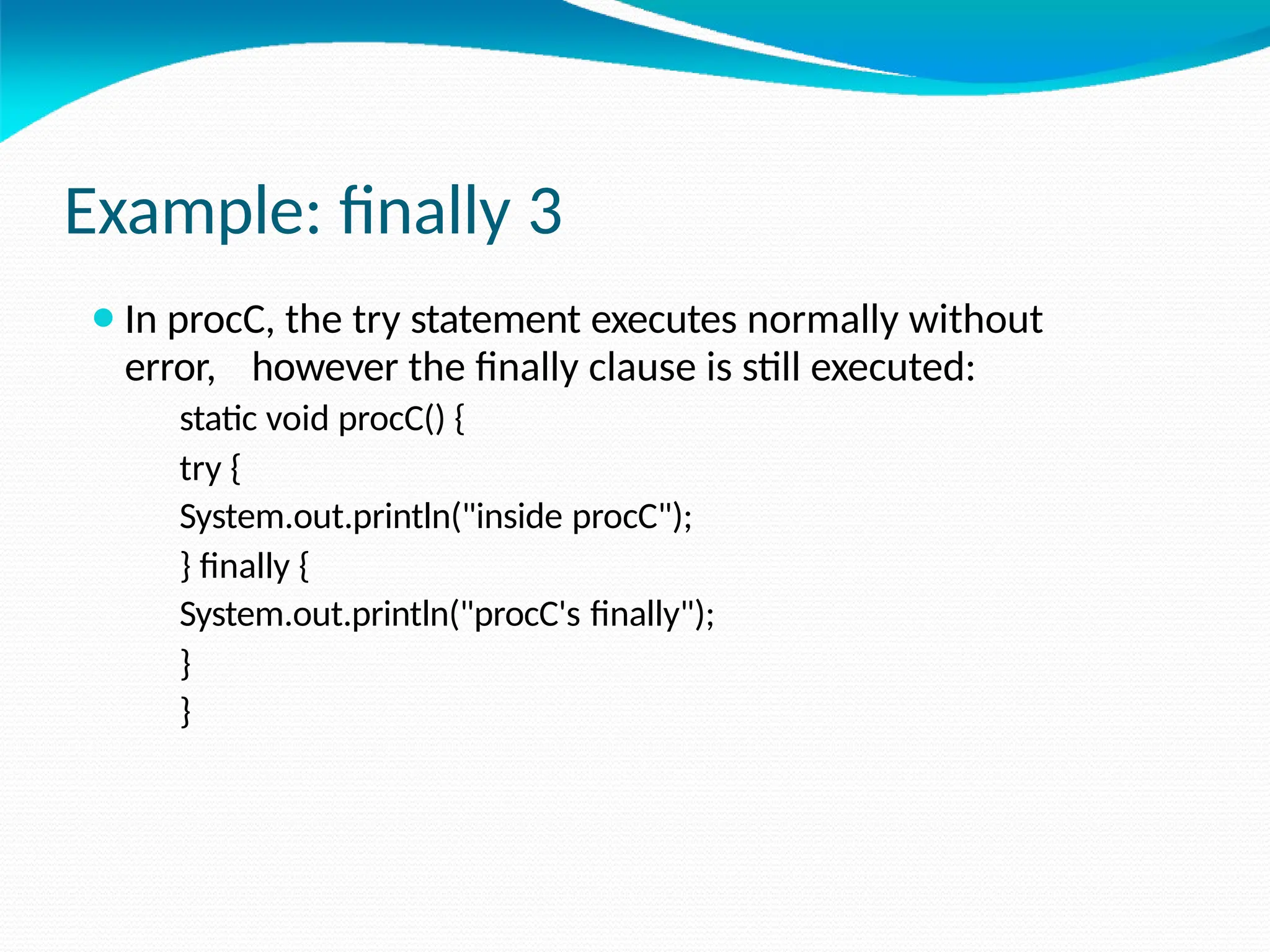

![Example: finally

4

⚫ Demonstration of the three methods:

public static void main(String args[]) { try

{ procA();

} catch (Exception e)

{ System.out.println("Exception

caught");

}

procB();

procC();

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javaunit3-250119180718-20ae97d7/75/PACKAGES-INTERFACES-AND-EXCEPTION-HANDLING-32-2048.jpg)

![Example: Own Exceptions 1

⚫A new exception class is defined, with a private detail

variable, a one parameter constructor and an overridden

toString method:

class MyException extends Exception {

private int detail;

MyException(int a) {

detail = a;

}

public String toString() {

return "MyException[" + detail + "]";

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javaunit3-250119180718-20ae97d7/75/PACKAGES-INTERFACES-AND-EXCEPTION-HANDLING-37-2048.jpg)

![Example: Own Exceptions 3

The main method calls compute with two arguments within a

try block that catches the MyException exception:

public static void main(String args[])

{ try {

compute(1);

compute(20);

} catch (MyException e) {

System.out.println("Caught " + e);

}

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javaunit3-250119180718-20ae97d7/75/PACKAGES-INTERFACES-AND-EXCEPTION-HANDLING-39-2048.jpg)

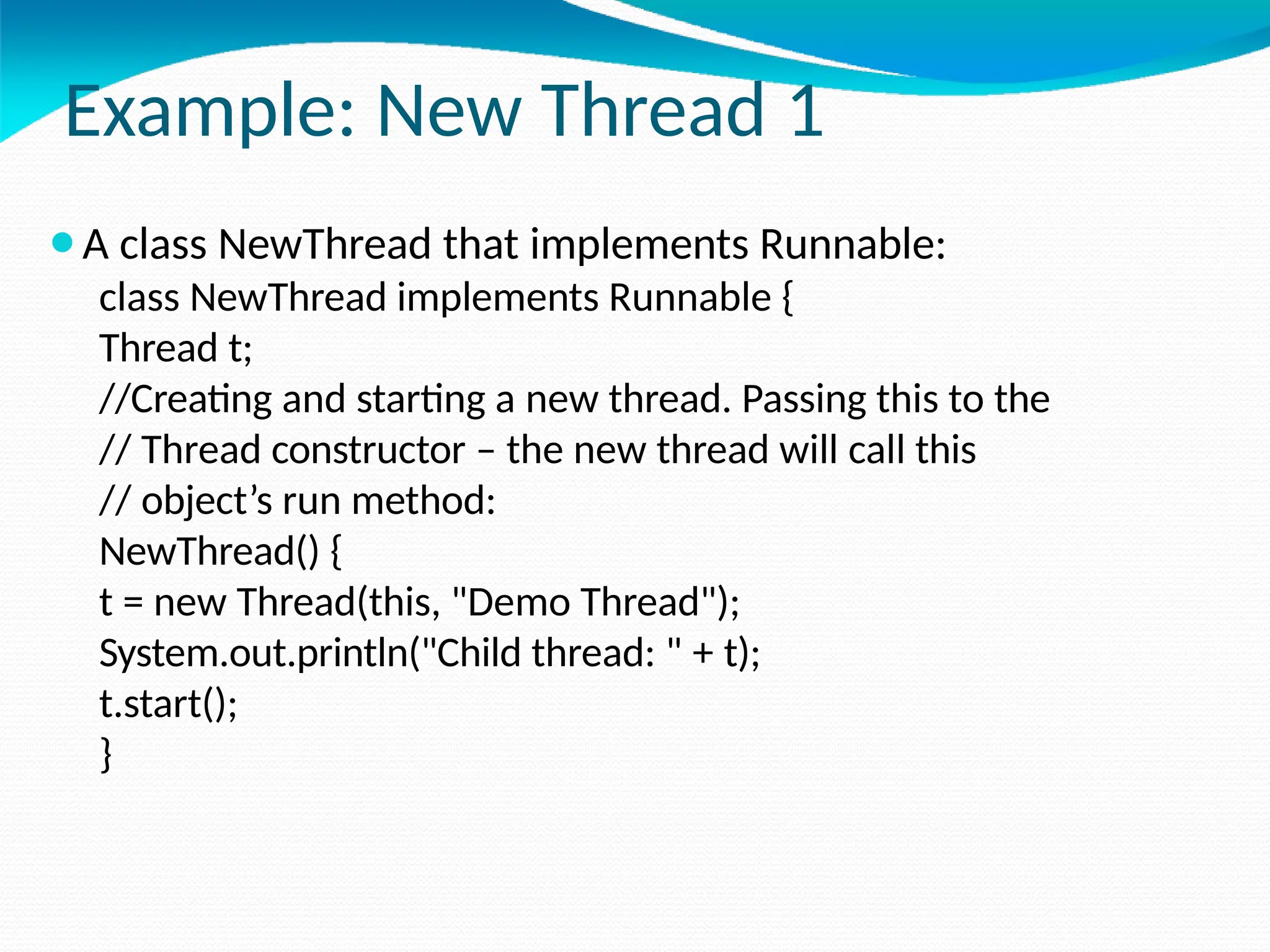

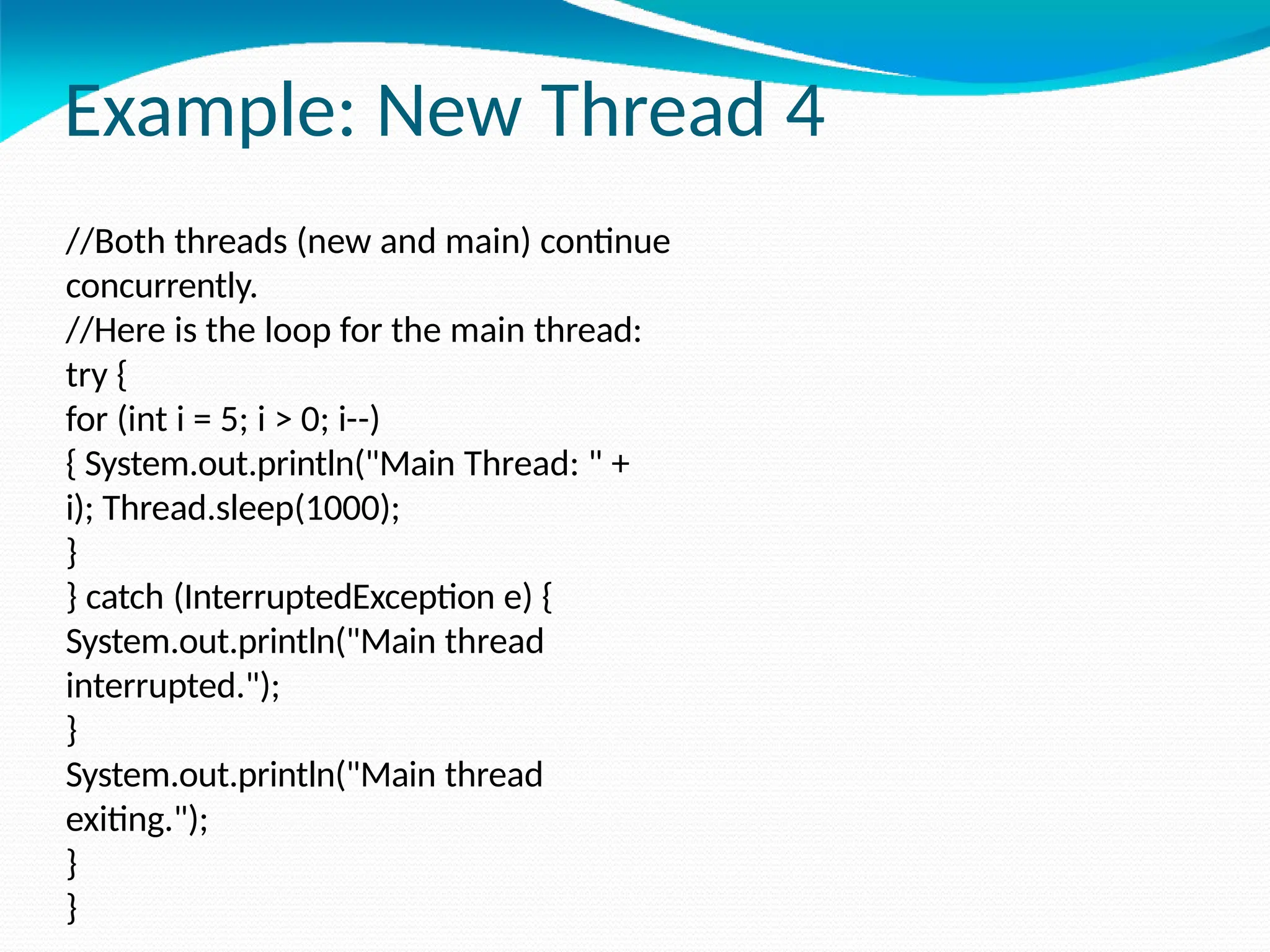

![Example: New Thread 3

class ThreadDemo {

public static void main(String args[]) {

//A new thread is created as an object of

// NewThread:

new NewThread();

//After calling the NewThread start method,

// control returns here.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javaunit3-250119180718-20ae97d7/75/PACKAGES-INTERFACES-AND-EXCEPTION-HANDLING-51-2048.jpg)

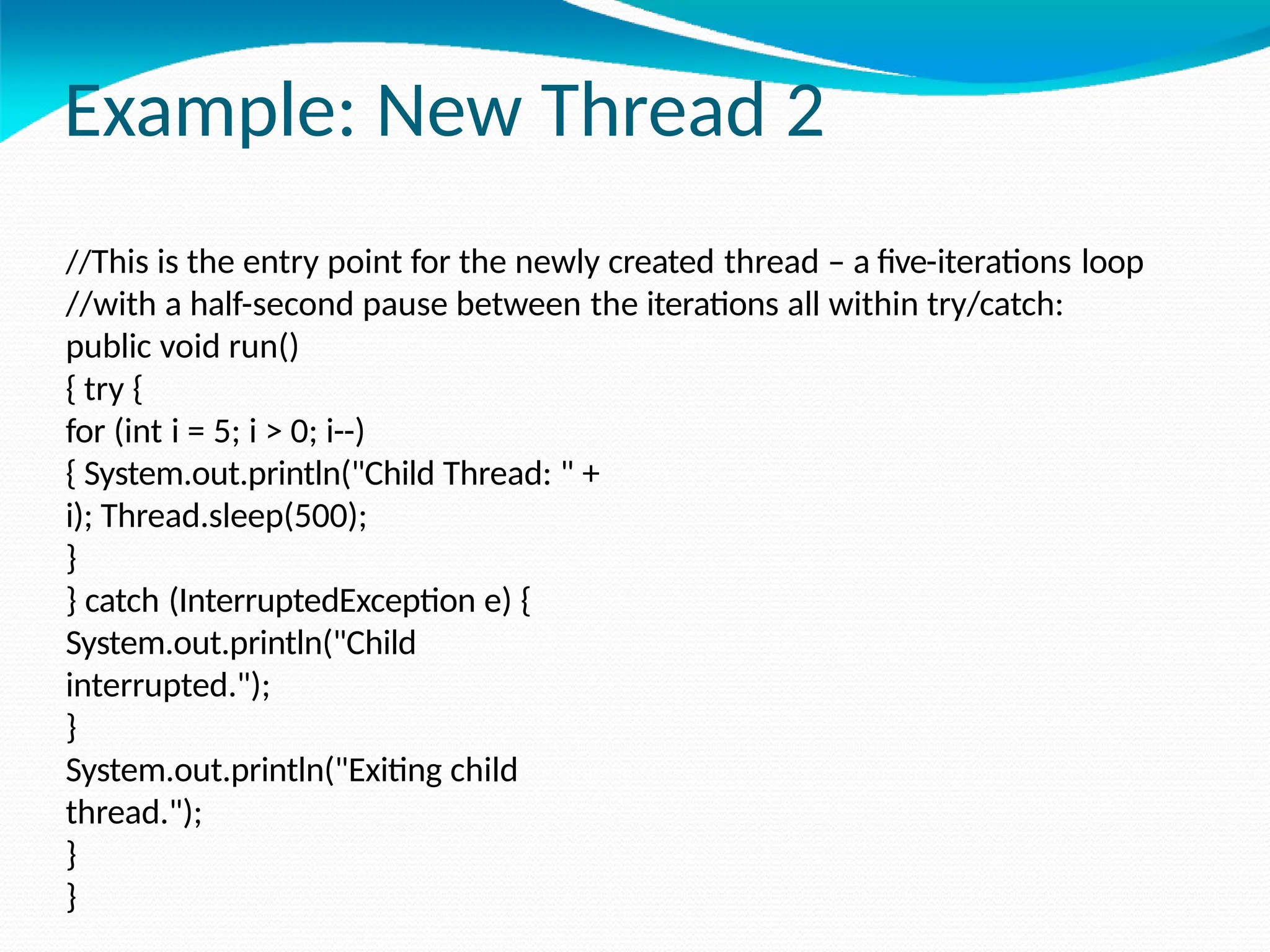

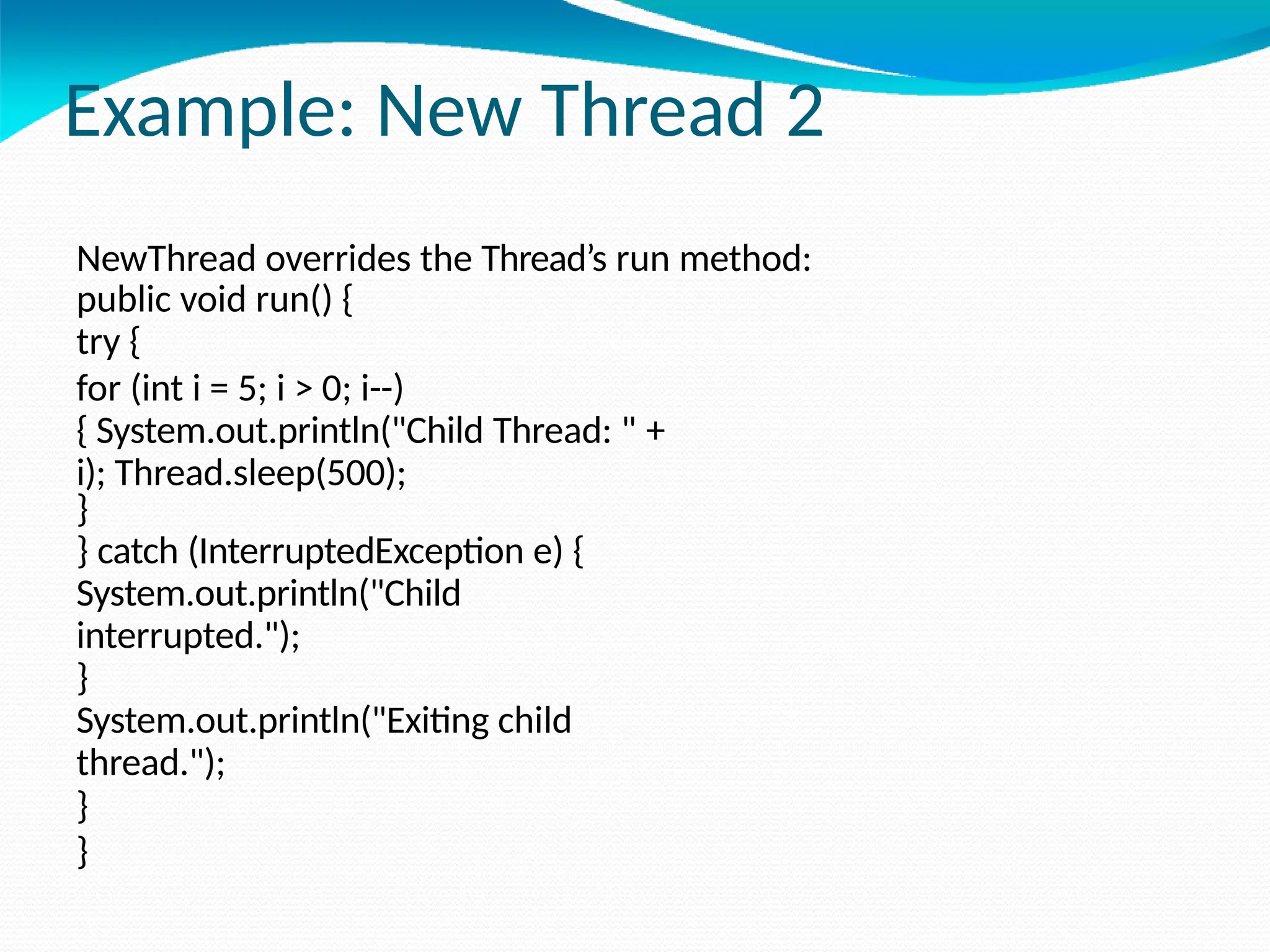

![Example: New Thread 3

class ExtendThread {

public static void main(String args[]) {

//After a new thread is created:

new NewThread();

//the new and main threads

continue

//concurrently…](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javaunit3-250119180718-20ae97d7/75/PACKAGES-INTERFACES-AND-EXCEPTION-HANDLING-56-2048.jpg)