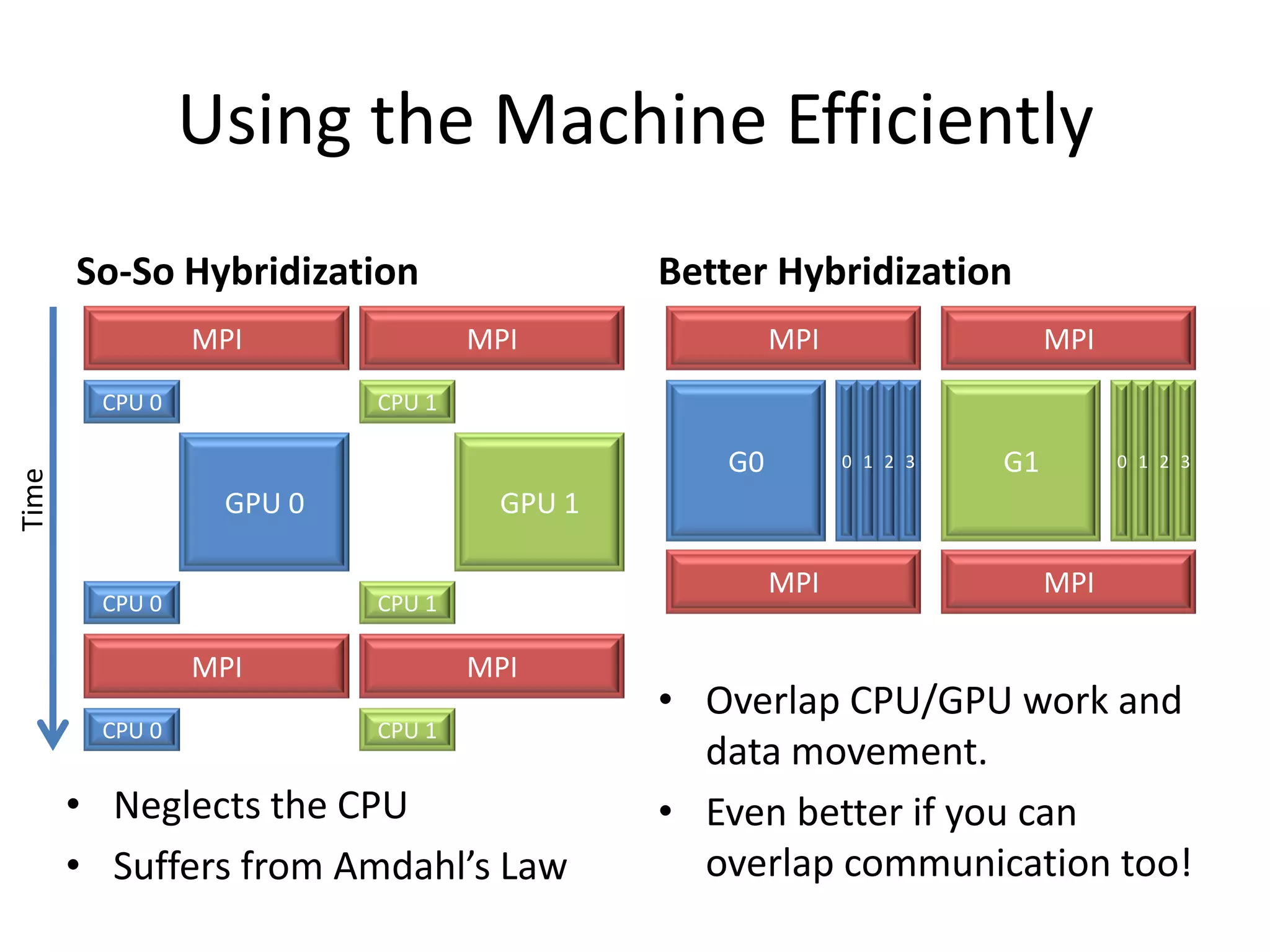

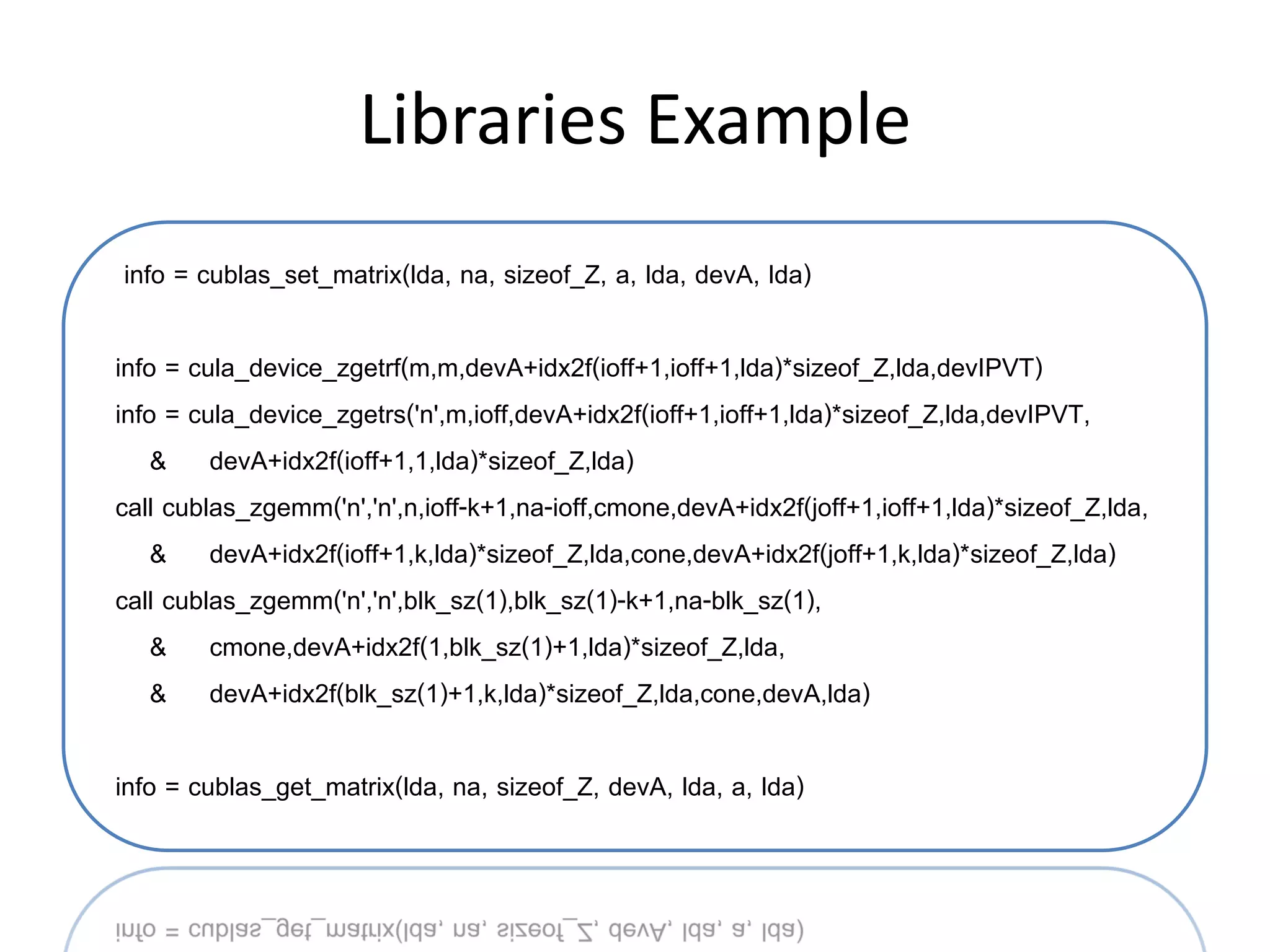

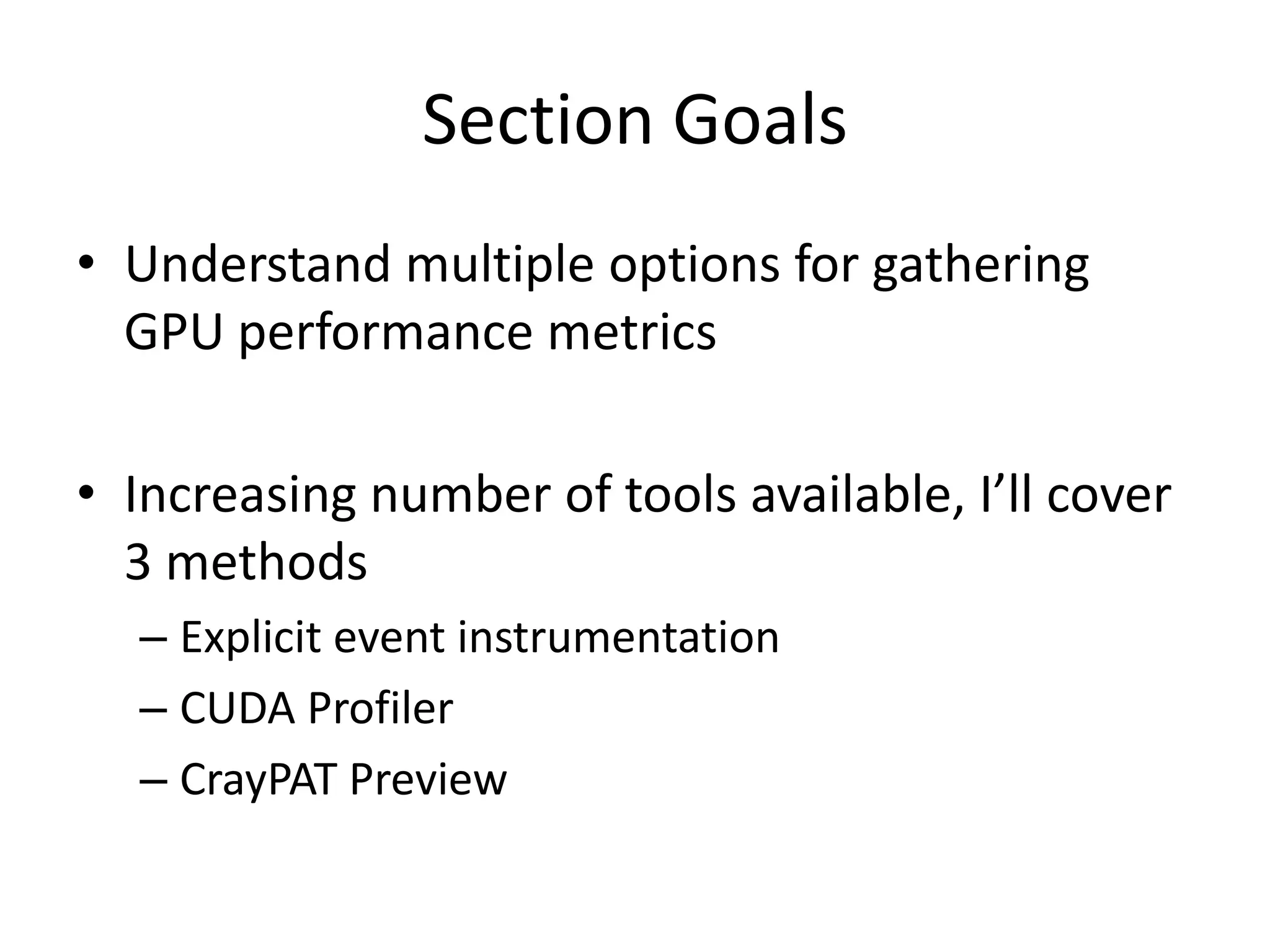

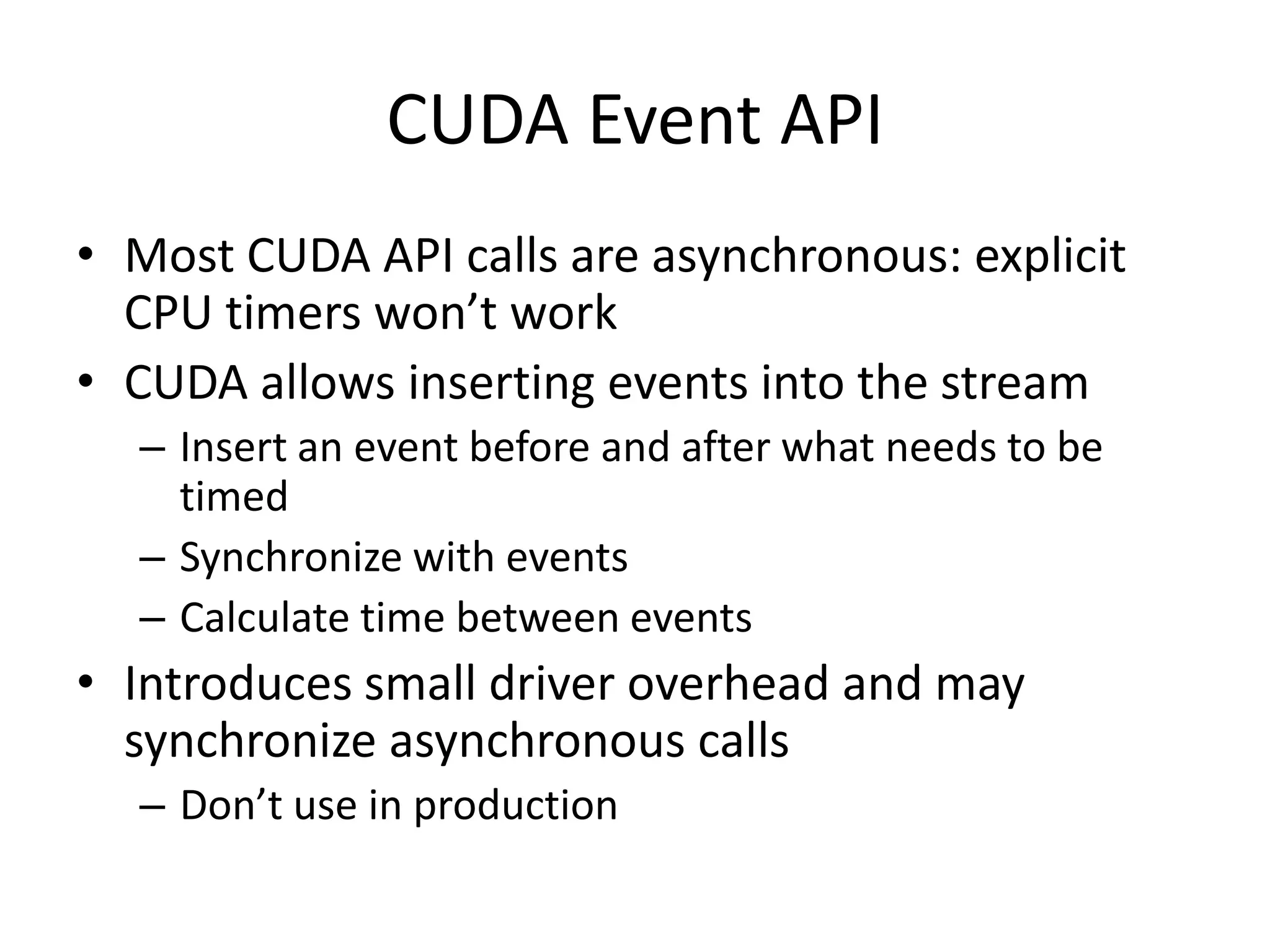

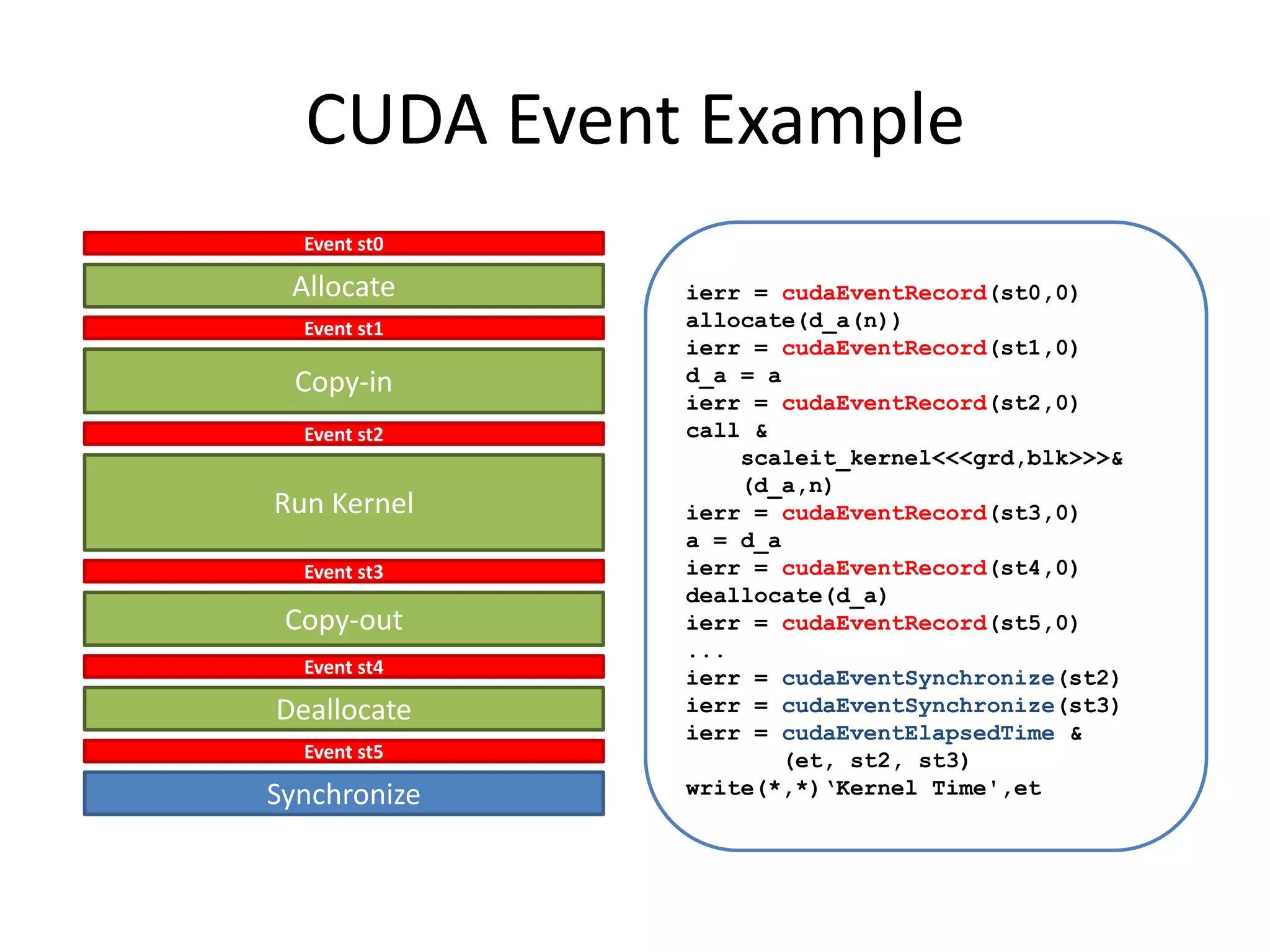

This document provides an introduction to GPU computing. It discusses the architectural differences between CPUs and GPUs and when each is better suited for certain tasks. It also overview several GPU programming models such as CUDA, OpenCL, and directives. Finally, it discusses approaches for analyzing GPU performance, including using explicit events, the CUDA profiler, and CrayPAT tools.

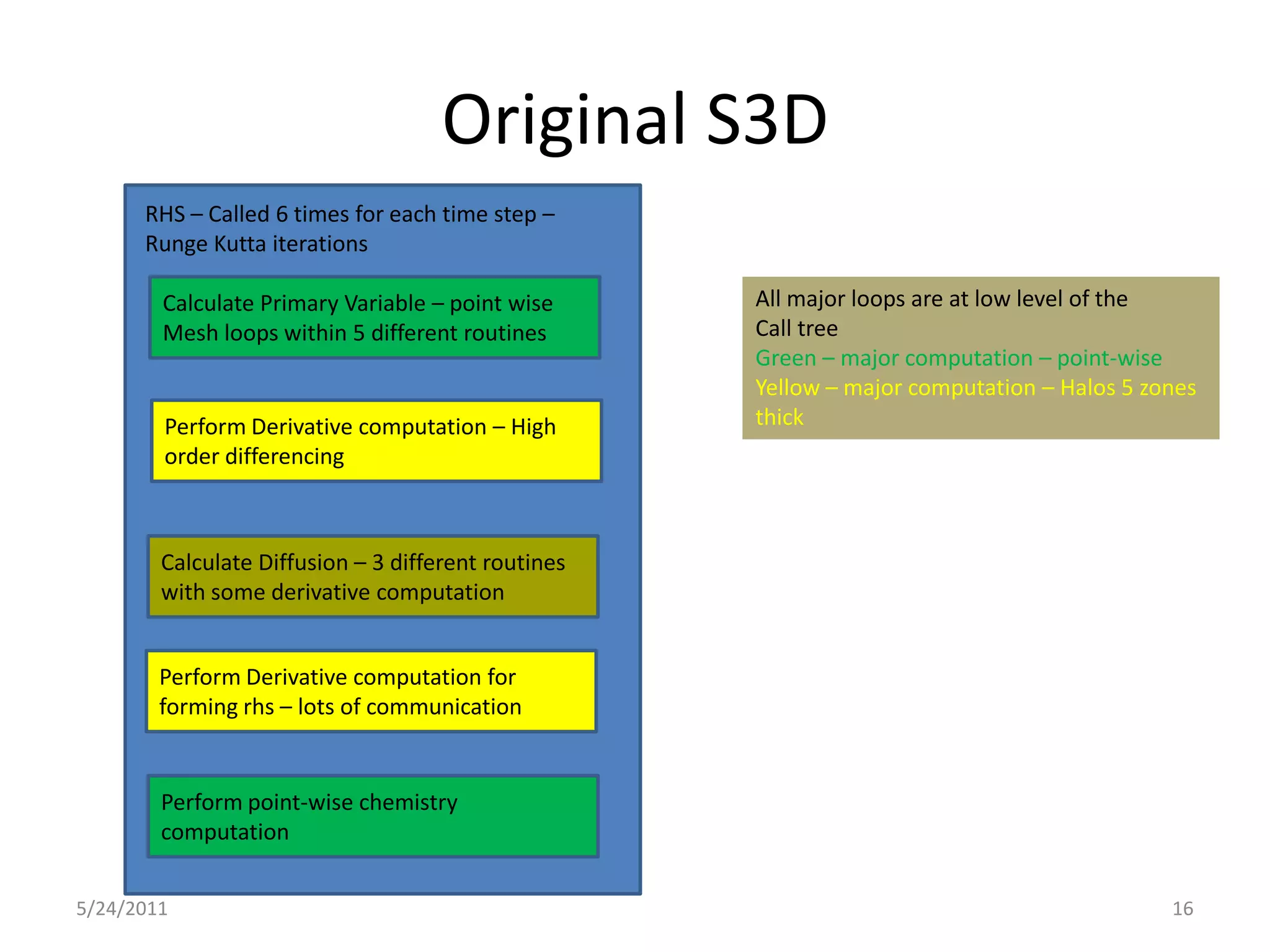

![CUDA C Example

Host Code GPU Code

Allocate &

double a[1000], *d_a;

dim3 block( 1000, 1, 1 ); Copy to GPU __global__

dim3 grid( 1, 1, 1 );

void scaleit_kernel(double *a,int n)

cudaMalloc((void**)&d_a, 1000*sizeof(double));

cudaMemcpy(d_a, a,

{

1000*sizeof(double),cudaMemcpyHostToDev

ice);

int i = threadIdx.x; My Index

scaleit_kernel<<<grid,block>>>(d_a,n); Launch

cudaMemcpy(a, d_a,

if (i < n)

Calculate

1000*sizeof(double),cudaMemcpyDeviceToH

ost);

a[i] = a[i] * 2.0l; Myself

cudaFree(d_a);

}

Copy Back & Free](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/larkintutorial-110523100034-phpapp01/75/CUG2011-Introduction-to-GPU-Computing-20-2048.jpg)

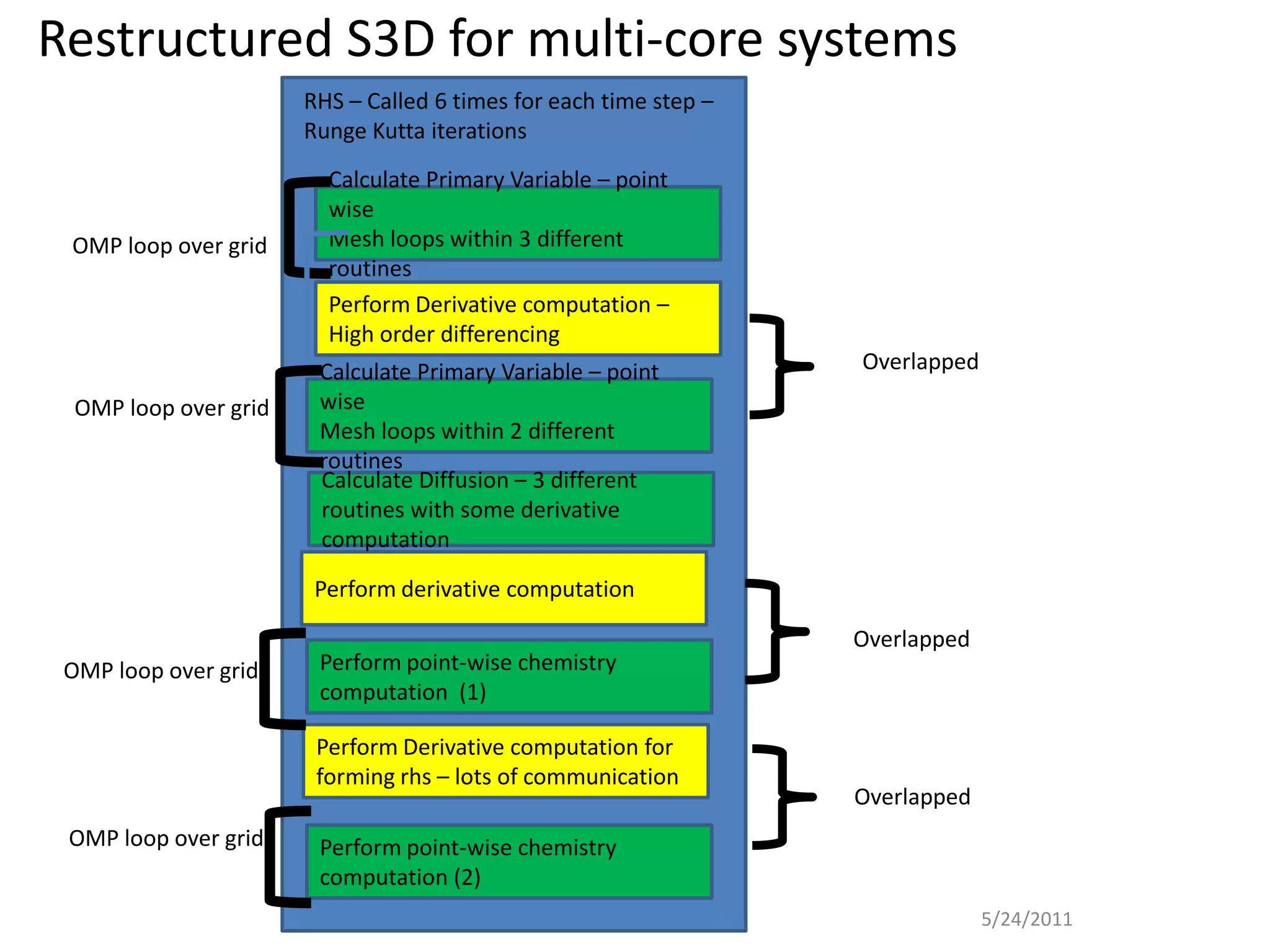

![CUDA Profiler Example

# Enable Profiler

$ export CUDA_PROFILE=1

$ aprun ./a.out

$ cat cuda_profile_0.log

# CUDA_PROFILE_LOG_VERSION 2.0

# CUDA_DEVICE 0 Tesla M2090

# TIMESTAMPFACTOR fffff6f3e9b1f6c0

method,gputime,cputime,occupancy

method=[ memcpyHtoD ] gputime=[ 2.304 ] cputime=[ 23.000 ]

method=[ _Z14scaleit_kernelPdi ] gputime=[ 4.096 ] cputime=[

15.000 ] occupancy=[ 0.667 ]

method=[ memcpyDtoH ] gputime=[ 3.072 ] cputime=[ 34.000 ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/larkintutorial-110523100034-phpapp01/75/CUG2011-Introduction-to-GPU-Computing-31-2048.jpg)

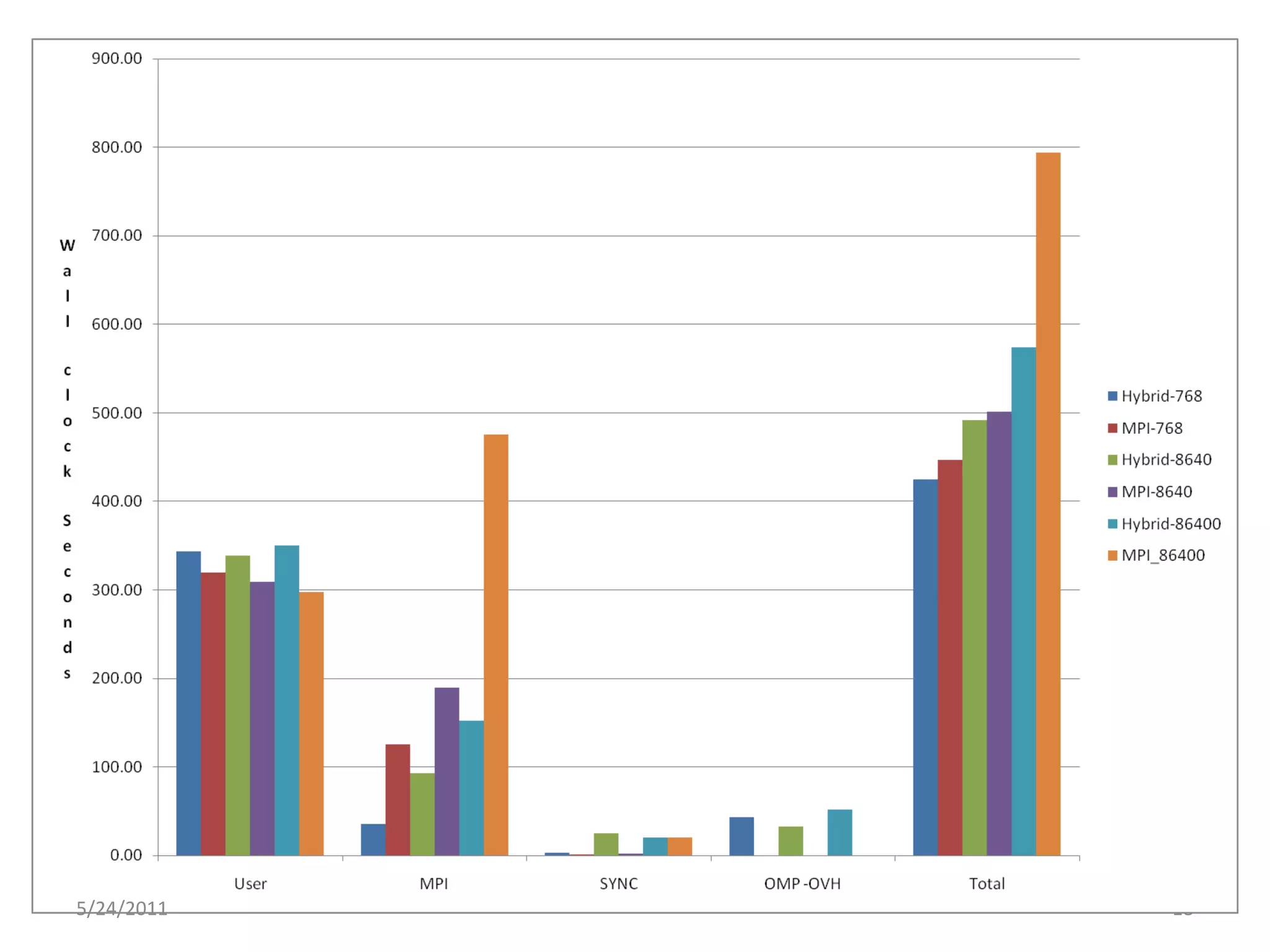

![CUDA Profiler Example

# Customize Experiment

$ cat exp.txt

l1_global_load_miss

l1_global_load_hit

$ export CUDA_PROFILE_CONFIG=exp.txt

$ aprun ./a.out

$ cat cuda_profile_0.log

# CUDA_PROFILE_LOG_VERSION 2.0

# CUDA_DEVICE 0 Tesla M2090

# TIMESTAMPFACTOR fffff6f4318519c8

method,gputime,cputime,occupancy,l1_global_load_miss,l1_global_load_hit

method=[ memcpyHtoD ] gputime=[ 2.240 ] cputime=[ 23.000 ]

method=[ _Z14scaleit_kernelPdi ] gputime=[ 4.000 ] cputime=[ 36.000 ]

occupancy=[ 0.667 ] l1_global_load_miss=[ 63 ] l1_global_load_hit=[

0 ]

method=[ memcpyDtoH ] gputime=[ 3.008 ] cputime=[ 33.000 ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/larkintutorial-110523100034-phpapp01/75/CUG2011-Introduction-to-GPU-Computing-32-2048.jpg)

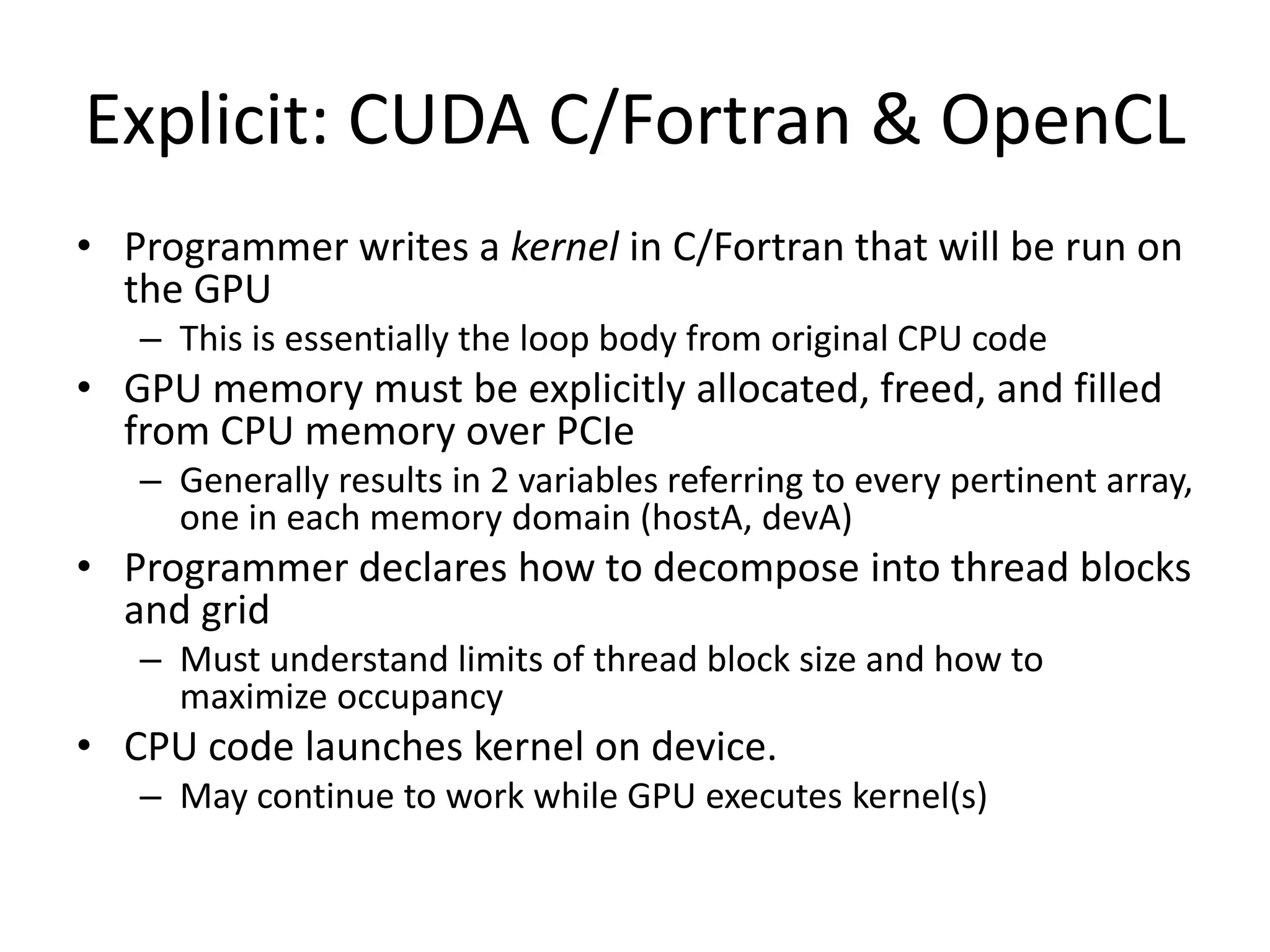

![Calculating Occupancy

1. Get the register count

ptxas info : Compiling entry function

'laplace_sphere_wk_kernel3' for 'sm_20'

ptxas info : Used 36 registers, 7808+0 bytes

smem, 88 bytes cmem[0], 768 bytes cmem[2]

2. Get the thread decomposition

blockdim = dim3( 4, 4, 26)

griddim = dim3(101, 16, 1)

3. Enter into occupancy calculator

Result: 54%](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/larkintutorial-110523100034-phpapp01/75/CUG2011-Introduction-to-GPU-Computing-40-2048.jpg)

![Simple Matrix Multiply

ptxas info : Compiling entry

attributes(global)&

subroutine mm1_kernel(C,A,B,N)

function 'mm1_kernel' for

integer, value, intent(in) :: N 'sm_20'

real(8), intent(in) ::

ptxas info : Used 22

A(N,N),B(N,N)

real(8), intent(inout) :: C(N,N) registers, 60 bytes cmem[0]

integer i,j,k

real(8) :: val

• No shared memory use,

i = (blockIdx%x - 1) * blockDim%x totally relies on

+ threadIdx%x

j = (blockIdx%y - 1) * blockDim%y

+ threadIdx%y

hardware L1

val = C(i,j) Kernel Time (ms) Occupancy

do k=1,N

val = val + A(i,k) * B(k,j) Simple 269.0917 67%

enddo

C(i,j) = val

end](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/larkintutorial-110523100034-phpapp01/75/CUG2011-Introduction-to-GPU-Computing-52-2048.jpg)

![Tiled Matrix Multiply

ptxas info : Compiling entry

integer,parameter :: M = 32

real(8),shared :: AS(M,M),BS(M,M) function 'mm2_kernel' for

real(8) :: val 'sm_20'

val = C(i,j) ptxas info : Used 18

registers, 16384+0 bytes

do blk=1,N,M

AS(threadIdx%x,threadIdx%y) = & smem, 60 bytes cmem[0], 4

A(blk+threadIdx%x-1,blk+threadIdx%y-1) bytes cmem[16]

BS(threadIdx%x,threadIdx%y) = &

B(blk+threadIdx%x-1,blk+threadIdx%y-1)

call syncthreads() • Now uses 16K of shared

do k=1,M

val = val + AS(threadIdx%x,k) &

memory

* BS(k,threadIdx%y)

enddo Kernel Time (ms) Occupancy

call syncthreads()

enddo Simple 269.0917 67%

C(i,j) = val

endif

Tiled 213.7160 67%](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/larkintutorial-110523100034-phpapp01/75/CUG2011-Introduction-to-GPU-Computing-53-2048.jpg)