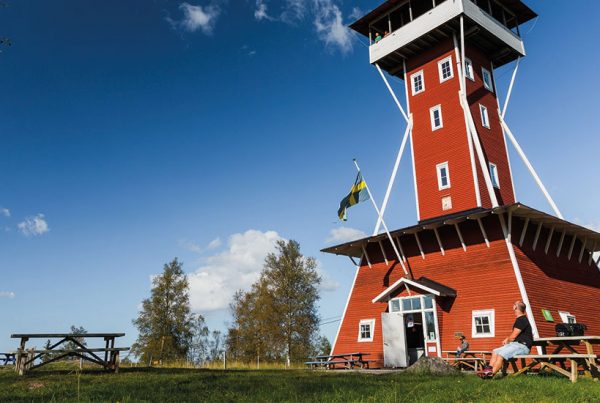

Kinnekulle – stone churches, manor houses, and floral splendour

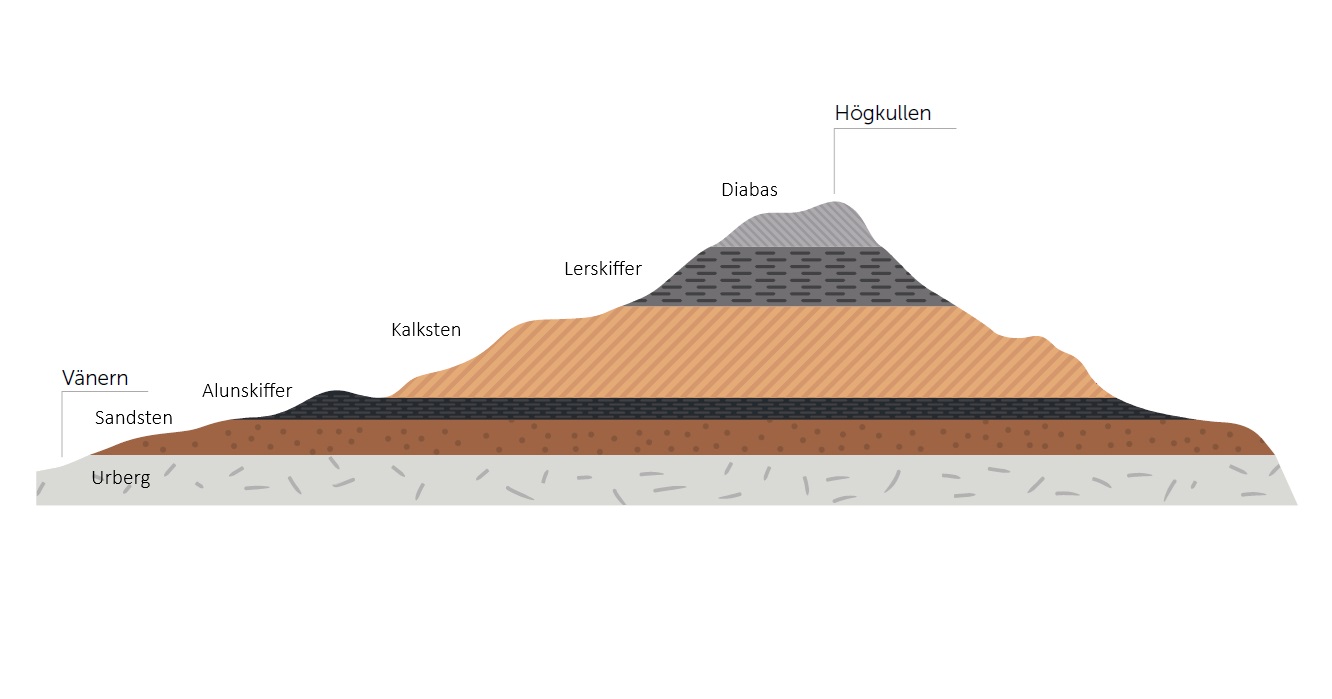

Kinnekulle is often used as a textbook example when explaining the geological structure of Sweden’s table mountains. Here, the entire sequence of layers is visible: Precambrian bedrock, sandstone, alum shale, limestone, clay shale, and, at the very top, dolerite. The summit reaches 308 metres above sea level, but the dolerite cap is only about ten metres thick. This is why Kinnekulle has its distinctive conical shape and lacks the broad dolerite plateau seen on many other table mountains.

Kinnekulle’s stratigraphic sequence from bottom to top: Precambrian bedrock, sandstone, alum shale, limestone, clay shale, and dolerite.

The mountain’s striking silhouette, visible from far and wide, has given rise to legends claiming Kinnekulle to be an ancient volcano. To put an end to these rumours, the polar explorer S. A. Andrée carried out his own excavation below the site where the viewpoint tower stands today. He demonstrated that Kinnekulle is not volcanic in origin, but that the dolerite rests directly on clay shale. Carl Linnaeus also recognised early on that Kinnekulle was something truly special, describing it as “one of the most remarkable places in the realm.”

Along the limestone ascent, it is also possible to clearly see the so-called highest shoreline, marking the maximum level reached by the sea when the inland ice melted and the land slowly began to rise. Waves once crashed against the limestone, sculpting the rock into rauk-like formations that can still be seen today, especially in the Munkängarna Nature Reserve on the western side of the mountain.

From rock carvings to manors and estates

Human presence has shaped Kinnekulle since the Stone Age, as evidenced by burial grounds, rune stones, and clearance cairns. At Flyhov lies Västergötland’s largest rock-carving site, with more than 450 motifs carved into the sandstone – images that speak of humanity’s need to tell stories and preserve memory. Archaeological finds show that the area was once wealthy and influential, and new discoveries continue to add chapters to its history. It is also said that this was where Swedish history took a decisive turn, when King Olof Skötkonung was baptised at Husaby Church and converted to Christianity, underscoring the site’s long-standing importance.

Kinnekulle is dominated by limestone and sandstone plateaus, with layers of alum shale in between. This geology has created a varied landscape of farmland, grazing land, and forest. Its position by Lake Vänern provided fishing and transport routes, while fertile soils brought prosperity. As a result, a string of manor houses and estates developed around the mountain. By the 16th century, Västergötland had become the most aristocrat-dense province in Sweden, and Kinnekulle was home to many noble estates. These manor houses left a lasting imprint on the landscape and reflect a period when estate culture flourished during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries.

Stonecutters and stone churches

Stoneworking has a long tradition on Kinnekulle. The most visible traces are the many medieval stone churches dating from the 12th and 13th centuries. Built using limestone and sandstone quarried from the mountain, they were financed by powerful families with extensive resources and connections. Kinnekulle became a centre of stonecutting, and its stone was also used for baptismal fonts, grave monuments, and the distinctive carved lily stones. At Forshem Church, visitors can explore a small stone museum displaying funerary art spanning seven centuries.

Limestone was also quarried for mortar production and soil improvement. Initially carried out on a small scale, with most households having their own quarry, extraction increased dramatically with industrialisation in the 19th century, leaving clear marks on the landscape. The most famous site is the Great Quarry (Stora stenbrottet), now a much-loved destination thanks to its dramatic rock formations and sweeping views over Lake Vänern.

Industry, workers’ housing, and living heritage

The community of Hällekis developed at the foot of Kinnekulle as a classic industrial settlement, deeply shaped by the lime and cement industries. Towards the end of the 19th century, factories were established in the area, and the growing workforce created a demand for housing close to the workplace. Between 1896 and 1898, the first workers’ dwellings were built at Falkängen: eight multi-family houses along Falkängsvägen constructed for employees of the cement works. Today, Falkängen has been transformed into a visitor destination with small shops, cafés, accommodation, and a museum, where the history of the buildings has been carefully preserved and the story of Hällekis as an industrial community lives on.

Another place where industrial heritage remains very much alive is Råbäck’s Mechanical Stoneworks, a working-life museum dedicated to keeping the craft of stone processing alive. Alum shale has also been widely exploited over the years, giving rise on Kinnekulle to extensive industries involving burning and oil extraction, traces of which can still be seen today. Read more about the fascinating history of alum shale, from industrial resource to motor-racing track, here (swedish).

Cherry blossom and wild garlic buds

As on other table mountains, the geology of Kinnekulle creates unusual biological diversity, but here it bursts into full bloom. Haymaking, grazing, and the thin soils of the limestone plateau have shaped a unique alvar landscape, where orchids such as early purple orchids flower in spring. The limestone enriches the soil with lime, favouring many plant species. Cherry and apple trees thrive here, along with wild garlic and the rare lady’s slipper orchid.

It is no coincidence that Kinnekulle is known as “the flowering mountain.” In 1924, the Swedish Tourist Association wrote of “the white and pale pink seas of blossom on the cherry-rich slopes in early summer.” During the first half of the 20th century, “Cherry Sundays” were also celebrated here, when ripe cherries were picked and sold to visiting guests.

The park-like gardens of the manor houses continue to contribute to this reputation. At Hellekis Estate, for example, visitors can see a ginkgo tree more than a hundred years old, alongside walnut, sweet chestnut, and other uncommon species. The mountain’s slopes and its position by Lake Vänern have always attracted both people and plants to put down roots here.

For more information about hiking trails, facilities, visitor attractions, and much more, visit the official Kinnekulle destination website.