Qatar may only be about the size of Connecticut, but the gas-rich Gulf emirate has outstripped its physical limits to become one of the most influential foreign players in geopolitics. Fueled by immense wealth and a willingness to engage with adversaries others avoid, Qatar—with just over 3 million residents, most of them foreign workers—has positioned itself not just as a mediator in Middle East conflicts but as an outside power broker in Donald Trump-era America.

But this rise has sharpened the paradox at the heart of the Washington-Doha relationship. Qatar is a key military partner and host of America’s largest base in the region. It is also the chief back channel for and sponsor of Hamas, criticized for harboring the Palestinian militant group’s leaders and accused of tolerating—if not outright supporting—extremist financing. Praised for its ability to get Hamas to the negotiating table and condemned for the cozy relationship that allowed it do so in the first place, Qatar is both neutral and, to many across the political spectrum, suspect.

“I wouldn’t call them friend or enemy,” said Natalie Ecanow, a fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, speaking on Newsweek’s The 1600 podcast in October. “It’s more like a frenemy. And that ambiguity is their strength.”

In 2025, that ambiguity collided head-on with U.S. policy under President Trump. After a surprise Israeli strike in Doha targeting Hamas leadership in September—the first time Israel had targeted Qatari soil—Qatar helped to broker the ceasefire that led to the release of all the remaining living Israeli hostages in Gaza last month. In the run-up to the deal, Trump signed an executive order pledging U.S. military protection to Qatar in the event of an external attack, and Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth announced the U.S. would host Qatari troops for training purposes at a military base in Idaho.

Some analysts saw that one-two punch of security guarantees followed by a military sweetener as the Trump administration’s “carrot” to Qatar for its help in the Gaza deal, whereas Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s airstrikes provided the “stick.” “I certainly see it as a thank you. And if not a thank you, certainly as part of what I view as a series of events or tokens of appreciation that have come either from Trump or from Netanyahu over the past month since that pivotal Israeli strike in Doha,” Ecanow said. “That sort of helped the Qataris turn the screws on Hamas and get a deal across the finish line.”

How Qatar Got Here

Qatar has steadily worked to position itself as a major soft power through cultural, diplomatic and humanitarian efforts. Like many Middle Eastern nations, its wealth is rooted in fossil fuel extraction—roughly 86 percent of its exports—transforming it from a modest pearl-diving economy into a leading petrostate. “Qatar’s possession of one of the largest reserves of natural gas in the world propelled its rise to prominence as a global supplier of liquefied natural gas from the mid-1990s on,” said Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, a fellow at Rice University’s Baker Institute of Foreign Policy. “That enabled heavy spending on entities such as Al Jazeera, Qatar Airways, and educational initiatives that established Doha as an emerging regional hub in the Arab world.”

Winning the bid to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup—a stinging defeat for the U.S. effort—boosted Qatar’s global profile and helped attract major fashion, sports and cultural events. But none of that mattered when, in June 2017, the country was isolated by its Gulf neighbors. The blockade, led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, triggered a geopolitical crisis. Flights were grounded, borders sealed and goods delayed. The stated reasons were Qatar’s support for the Muslim Brotherhood and ties to Iran, but the subtext was a regional power struggle.

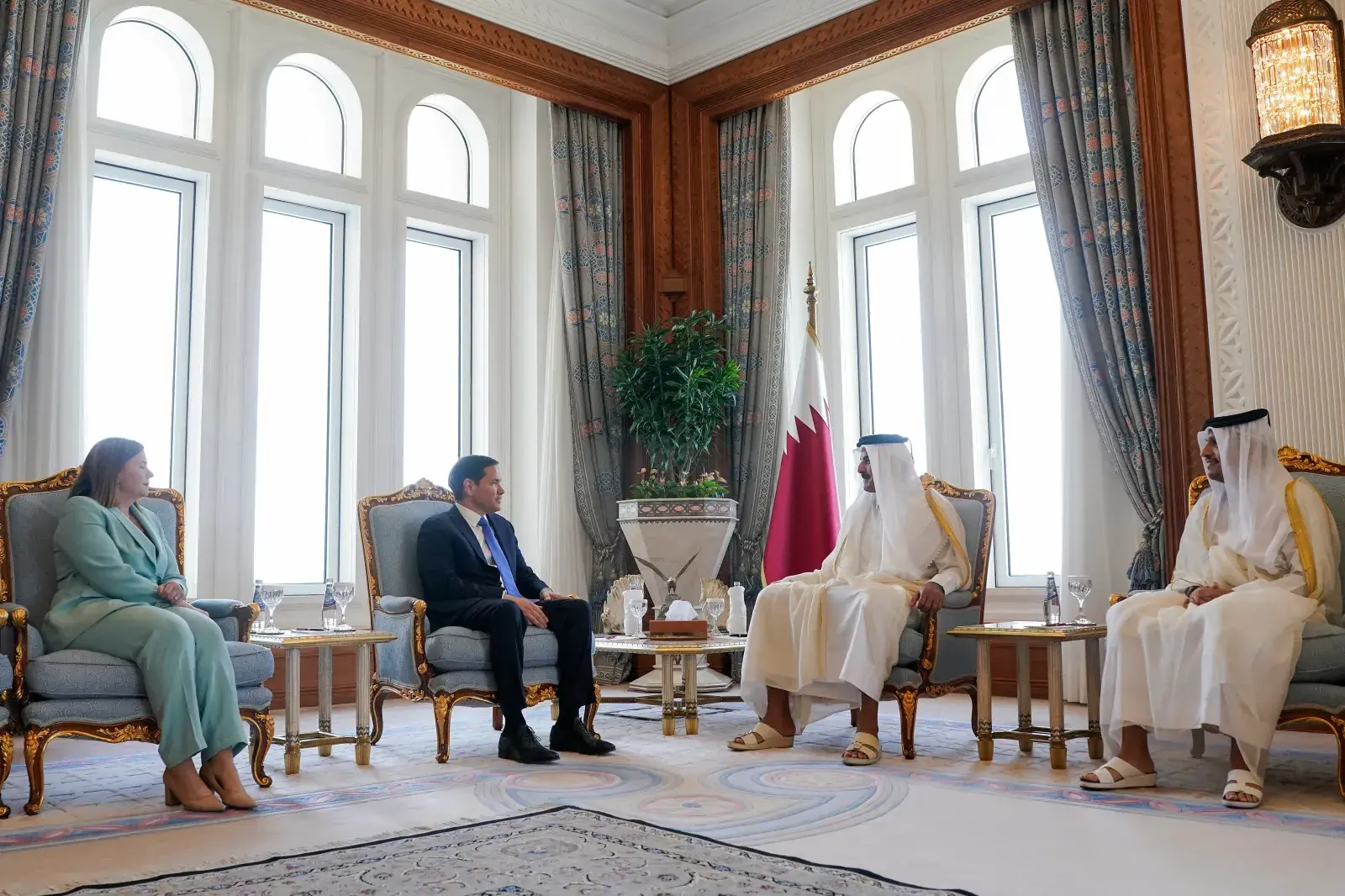

“That was an enormous wake-up call for the Qataris, not just because they would have been outgunned on the battlefield, but because they were woefully outflanked in an, arguably, even more important source of power—influence in Washington, D.C.,” Ben Freeman, director at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, told Newsweek. “This helped to pave the way for the Qatari emir to sit down with Trump in the White House less than a year after Trump was seemingly encouraging an invasion.”

“When it was threatened with invasion by its neighbors during the Gulf Cooperation Council spat, Qatar was caught flatfooted and realized it needed to buy influence in Washington,” Nick Cleveland-Stout, a research associate at the Quincy Institute, told Newsweek. “Armed with a cadre of lobbyists to market itself in Washington D.C., Qatar has successfully become the new capital of regional and even international diplomacy.”

Qatar began flooding K Street with money. In the year following its diplomatic crisis with neighboring states, Doha spent $18 million across 33 firms—many led by Republicans with ties to Trump, according to a Quincy Institute report. The Qataris also invested in firms and staffers with close relationships to Democrats. “Foreign influence is a bipartisan affair,” Cleveland-Stout said. “Perhaps Qatar’s most well-known lobbyist is Jim Moran, a former Democratic lawmaker,” he added. The campaign included everything from media outreach to back channel deals. The Quincy Institute report said one firm targeted 250 key influencers to reshape Trump’s perception of Qatar. Another organized junkets for right-leaning figures and commentators. “They offered access, hospitality and a different narrative,” said Ecanow from the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. “And it worked.”

Ali Al-Ansari, Qatar’s media attaché to the U.S., told Newsweek: “Qatar’s strategic partnership with the United States is built on decades of cooperation across a range of shared interests.... One consequence of our deepening partnership has been the launch of large-scale disinformation campaigns against Qatar by bad actors who are threatened by the Qatar-U.S. partnership and do not want it to succeed. These actors thrive on chaos and instability and do not want peace to prevail because it does not serve their interests. As a result, lobbying has become necessary as a defensive measure to prevent falsehoods from being accepted as fact in Washington and among the American public.”

By the end of Trump’s first term, Qatar had more than tripled its foreign lobbying spending, the report found, surpassing regional rivals like Saudi Arabia and the UAE. From 2021 to 2025, Foreign Agents Registration Act disclosures show Qatar’s lobbyists logged more in-person meetings with U.S. officials than any other country—627. That power became political leverage. In Congress, lawmakers once skeptical of Qatar began shifting. Some, like Senator Lindsey Graham, became frequent points of contact. Doha also poured more than $6 billion into U.S. universities, mostly to fund branches in Qatar. Those with campuses there include Georgetown, Northwestern and Texas A&M. Qatar also emerged as a top foreign donor to Washington think tanks. “They built relationships with both sides,” said Ecanow. “They were never naive about Washington. They understood that influence is cumulative.”

Two Faces of the Emirate

That same access fuels suspicion, even from MAGA ranks. The executive order signed by Trump was the most explicit U.S. security guarantee to Qatar to date, taking the Gulf monarchy into the highest tier of American non-NATO defense relationships. But it came less than two years after some in Congress pushed legislation to strip Qatar of its major non-NATO ally status over its ties to Hamas. That contradiction isn’t lost on critics or supporters.

“The defense guarantees they now have are unprecedented,” said Bilal Y. Saab, a former Pentagon official and senior managing director of TRENDS US, a strategic consulting firm based in Washington, D.C. “Its usefulness [is] as a mediator, willing and able to talk to entities the U.S. government and many of its partners find abhorrent or classify as terrorist.”

“Qatar is showing how the U.S. political system really works,” said Quincy Institute’s Freeman. “If you have a lot of money you can bend it to your will. They are playing the game perfectly right now and that is why they’re getting nearly everything they want from the Trump administration.” That leverage has become central to how Doha pitches itself in Washington: as a state willing to engage the unengageable while giving the U.S. a platform to operate in the region. It’s a delicate posture that’s invited scrutiny, especially from lawmakers skeptical of Qatar’s role in the Israel-Hamas conflict.

From the MAGA-aligned right, there is open discomfort with the arrangement. “They don’t like that Qatar is being elevated as a partner while still refusing to distance itself from groups seen as terrorists,” said Ecanow. “There’s real pressure within the conservative base for answers on that.”

Far-right commentator Laura Loomer has been especially vocal. “This is really going to be such a stain on the admin if this is true,” she posted on X. Other nationalist influencers and lawmakers from both sides of the aisle have cast Qatar as a foreign power meddling in American priorities under the guise of diplomacy. The backlash has extended to Qatar’s media and messaging power. Long accused of shaping anti-Western narratives through its state-run outlet Al Jazeera, Qatar has come under fire for its indirect influence on U.S. media. In 2023, a Qatari royal invested $50 million in Newsmax, a conservative-aligned network that soon after began softening its tone on Qatar. “That’s the risk,” Freeman said. “The U.S. just committed its soldiers to defend a monarchy that has directly enriched the president’s inner circle. That’s not a partnership—it’s a tripwire.”

What’s Next for Qatar?

Yet Qatar’s position in Washington looks more secure than ever. The defense guarantees inked in 2025 formalized what had long been understood: Qatar is now an ally with near-Article 5 protections.

“The new defense commitments are a reaffirmation and upgrading of an already-close partnership that goes back decades,” said Coates Ulrichsen. “The benefit Qatar brings is that it is able to be an intermediary that maintains channels of indirect contact between the U.S. and adversaries such as Hamas or the Taliban, particularly at times of tension.”

Qatar’s position is unique for how entrenched it has become. Unlike Egypt or Saudi Arabia, which rely on overt statecraft and security deals, Qatar operates through relationships cemented through lobbyists, universities and behind-the-scenes negotiations—similar, in a way, to how Trump himself operates outside the bounds of typical diplomatic channels. Freeman, who has tracked Qatar’s foreign lobbying across multiple administrations, said the durability of the alliance is exactly what makes it risky. “Most of the power players in U.S. foreign policy have benefited enormously from Qatar’s largesse,” he said. “The question is what will happen when Qatari and U.S. interests are not aligned?”

“No partnership is perfect. Even the NATO treaty alliance, the most successful in world history, is riddled with problems,” said former Pentagon official Saab. “It will be up to the leaders of both sides to manage the U.S.-Qatar partnership and make the best of it. There is plenty of room for prioritization and compartmentalization. They don’t have to agree on everything.”

Some believe those contradictions can’t hold forever. Qatar took hits from all sides this summer—from Iran then Israel—testing its delicate balancing act. The attacks, said Coates Ulrichsen, “have brought home in a visceral way the risks of mediation in such turbulent times.” Ecanow put it more bluntly: “You can’t be both the mediator and the host for one side’s leadership. Eventually, that tension breaks.”