I once said that any filmmaker who has been working for a while should, at some point in their career, make a film about the process of making a film. It’s only natural to want to explore this complex and all-consuming subject to which we dedicate our passion and creativity. But what is the right approach? How do you find the right tone? Is it even possible to do better than Day for Night? Probably not.

Over the years, my thoughts always brought me back to the time I made my first feature that involved a lot of other people — to that absolute joy of finally being able to condense years of cinematic ideas and obsessions into a movie. It’s an experience you can only live once, of course. No one is ever truly prepared for the physical and mental battles that come with it: the clash between overwhelming confidence and deep insecurity due to inexperience, the boundless passion that is tested daily by the instability of a job involving so many people, each with their own personalities and needs.

When Jean-Luc Godard passed away two years ago, I thought to myself: “Maybe it’s time to make this film that’s been percolating for more than a decade; this portrait of that singular moment — the birth of the New Wave.” This love letter to those who made you want to make films, who made you believe you could make films, who convinced you that you should make films — and, by the way, what are you waiting for?

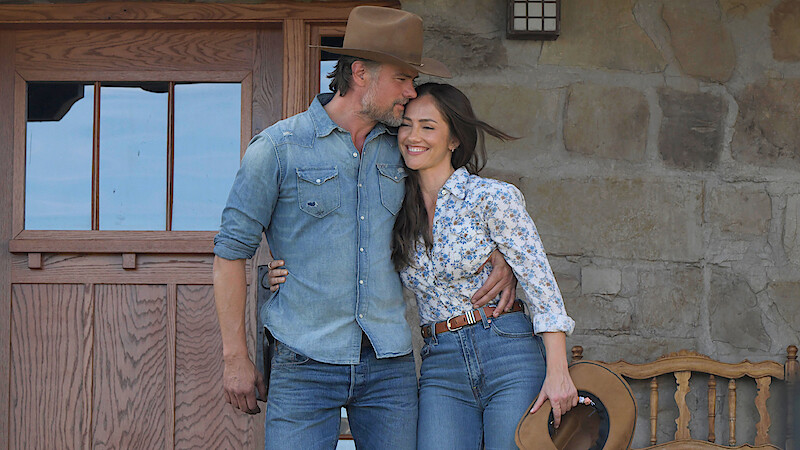

Star Guillaume Marbeck and director Richard Linklater

As far as I’m concerned, the French New Wave changed my life. I had just moved to a big city. I was 20 years old and still imagining myself as a future novelist or playwright. To me, cinema was Hollywood. I liked films well enough, but I had never considered making movies myself. When I saw Breathless and other New Wave movies, I thought: “So, it’s possible?” That freedom fascinated me. I didn’t know anything about filmmaking, but I could feel how cool, joyful, and revolutionary the movie was.

No one embodies the French New Wave better than Godard. He does what’s forbidden, he sketches, he improvises. I love his humor, his physicality, his audacity. He follows no rules, just his own cinematic consciousness. When he makes his first feature, he is lagging behind his friends from Cahiers du Cinéma. He is worried, anxious, afraid he has missed the wave. He believes in himself, but can’t help but be insecure and vulnerable. I find that very endearing and nothing like the way people will imagine him later in his career.

From where we stand today, Breathless is at the midpoint of cinema history. It now seems like the perfect moment to remind ourselves that cinema is eternally capable of reinventing itself. To paint a playful portrait of a tight-knit community of film fanatics who live, eat, and breathe cinema. To show that cinema is — and will always be — an inventive medium.

Aubry Dullin, Zoey Deutch and Marbeck

Nouvelle Vague is not about remaking Breathless, but looking at it from another angle. I want to dive into 1959 with my camera and re-create the era, the people, the atmosphere. I want to hang out with the New Wave crowd.

For the illusion to be complete, we needed to find actors who resembled their real-life counterparts and were unknown, so as not to break the spell of feeling that we are truly with Godard and his contemporaries. And, of course, we had to find someone who could embody this bold, tormented, fragile, and arrogant young filmmaker.

The casting process took more than six months. When I first brought together our Godard, our Truffaut, our Chabrol and our Schiffman, it was the decisive moment. It’s when I realized this film could work as I wanted, because they were right there in front of me and happy to be back together in 1959. I told all the actors, “You are not making a period film. You are living in the moment.”

Dullin and Deutch

Before we started, I gave them this text to read:

Godard was going for a spontaneity, an immediacy, as were many painters and jazz musicians of the time. The notion of improvisation was in the air, the epitome of cool. To achieve that kind of freedom, you either have to be spontaneously brilliant (good luck with that!) or work incredibly hard — fully examine each scene from every angle, know it so well, and be so relaxed with what we’re doing that it seems spontaneous and improvised.

Once you get past the lines themselves — the intentions of the scene — you can find another level of reality, where your full self can be revealed within the character. You must be so aligned with your character and those around you that all behavior, attitude, gestures, and relations will be authentic.

Important: You are not acting in a “period film.” This film does not carry any particular significance because of its age or reputation. The moments we’re creating, the characters involved haven’t earned any of that yet. As an actor you can only do what any of us can do going through life, simply live in your moment, with the excitement and optimism that come with youth and making art.

Marbeck, Deutch, and Dullin

Much of the underlying humor comes from the fact that our audience already knows the outcome. We are making them witnesses to the emergence of a singular cinematic artist, making one of the most talked about and influential films in history. But nobody in our film knows this.

There are only a few conflicts — namely with Beauregard, when it comes to schedule and money, and Seberg, to whatever degrees when it comes to working methodologies. But for the most part, you are all just happy to go along for the ride, and you have no idea if what you’re working on is any good or not.

Never forget that filmmaking itself is optimistic. And, as François Truffaut said at this time, “The film of the future will be an act of love.”

So now … let’s rock and roll!