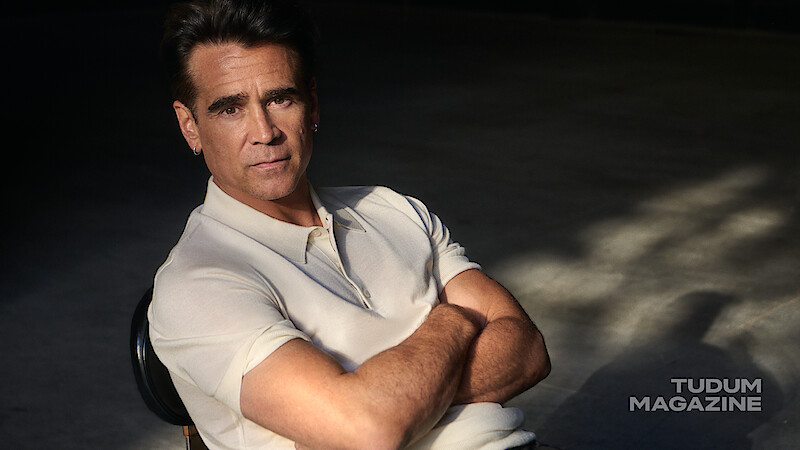

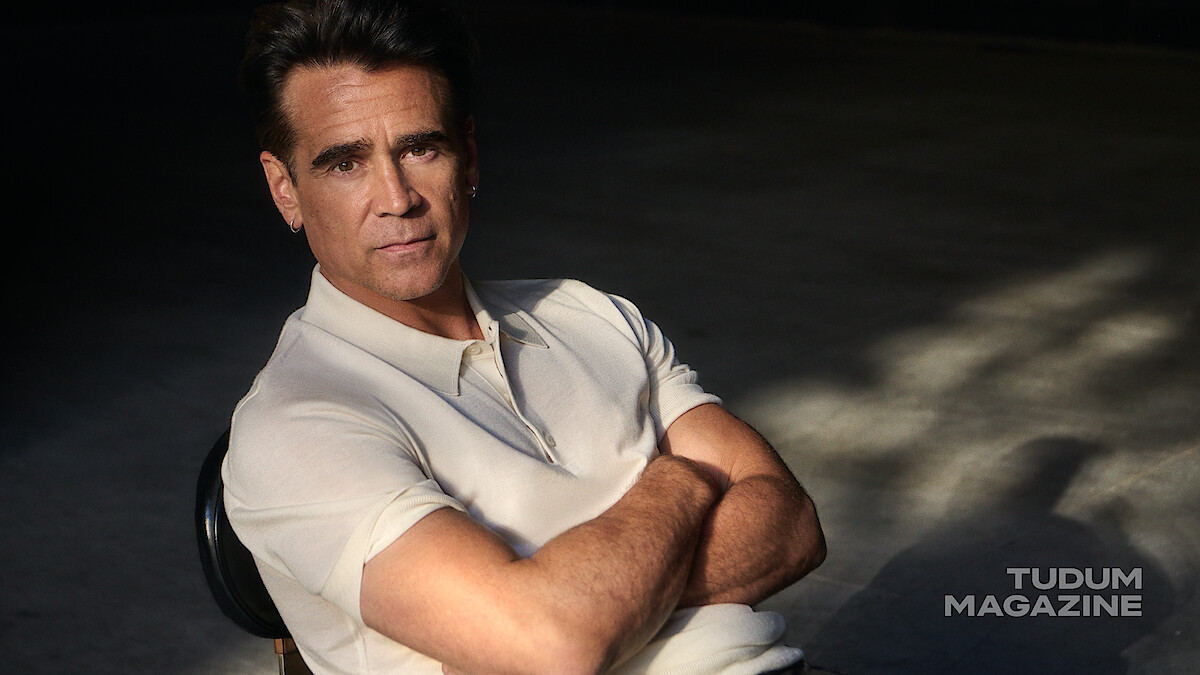

When we first meet the yellow-gloved Lord Doyle (Colin Farrell) in Ballad of a Small Player, he’s down more than $350,000. And he won’t stop there. As the film goes on, Doyle falls ever deeper into the seductive, neon-drenched world of the Macau gambling scene, until he can’t tell up from down or good money from bad.

“He’s running dry,” Farrell told Netflix. “And by the time we meet him, he’s been in Macau a while, and he’s blown through a lot of cash. He’s at the tail end of a phantasmagorical spree and entering the nightmare that the tale becomes.”

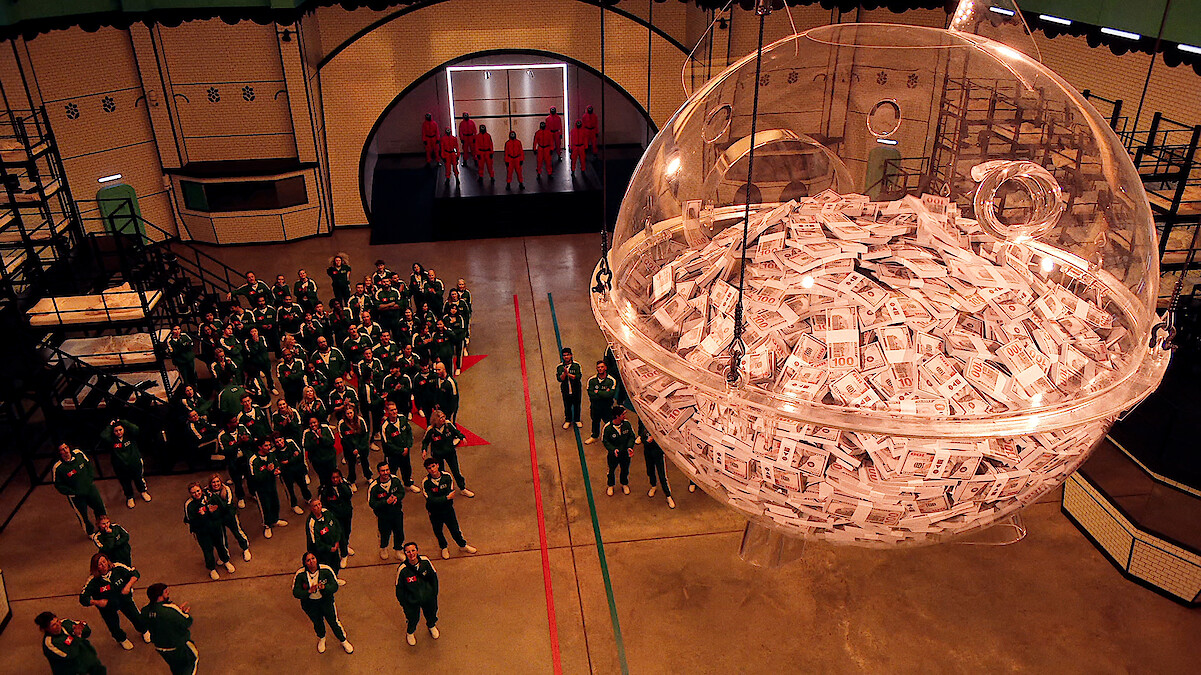

Adapted by Rowan Joffé from Lawrence Osborne’s 2014 novel, Ballad of a Small Player is a luminescent dive into the world of Macau and Doyle’s place in it. “I went to a Bruce Nauman exhibition in Hong Kong,” director Edward Berger tells Netflix. “He said that he was trying to make art that was ‘like getting hit in the face with a baseball bat.’ That’s what Macau felt like to me. It hits you with a baseball bat square in the face.”

As Doyle tries to get out of the hole, he finds himself at the mercy of the City of Dreams — and his own appetites. “He is, like most addicts, somewhat narcissistic and can only see the world through the lens of his own needs and his own desires,” Farrell says. “Deep down, fundamentally he is decent, but he has all of his lines mixed up and wires crossed.”

He also has his own secrets, including debtors on his tail and a complicated past he’d rather not revisit. Read on to find out more about the intoxicating world of Ballad of a Small Player — and whether Lord Doyle can escape it.

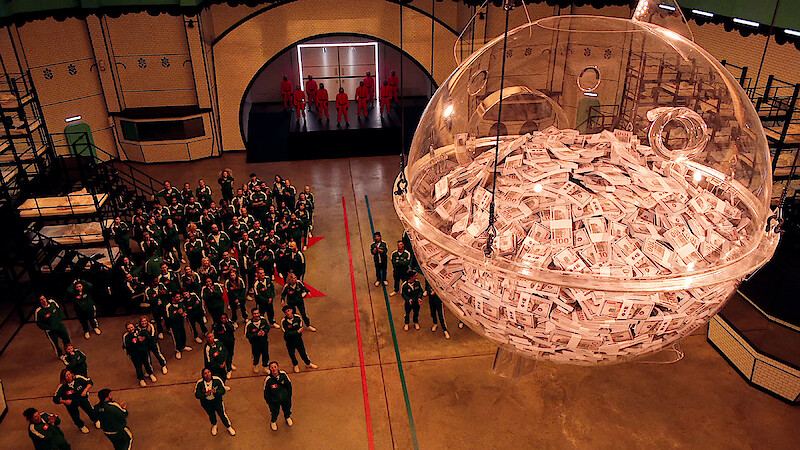

First, a helpful primer in punto banco baccarat, the high-stakes card game that Lord Doyle spends much of the film playing:

Aces are 1; 2 – 9 are face value; 10, jack, queen, and king are 0.

At the beginning of Ballad of a Small Player, Doyle has a few outstanding debts: 352,000 Hong Kong dollars (about $45,000 USD) to the hotel he’s staying in and almost a million more in UK pounds to a wealthy old woman whose portfolio he managed.

“He’s struggling, he’s somewhat in hock,” Farrell says. “He’s in hock to the hotel. He’s in hock to a couple of people around town. He owes money all around.” To make matters worse, private investigator Cynthia Blithe (Tilda Swinton) is snooping around for that UK client, reminding Doyle that there are still people out there who remember his real identity — working-class Irishman Reilly.

While playing against formidable Macau fixture “Grandma” (Deanie Ip), Doyle meets loan shark Dao Ming (Fala Chen), who offers Doyle a line of credit to try to get out of the hole. “She can spot a man in need, as part of her job is to loan money to gamblers with a high interest, and that’s how she makes a living,” Chen says. “Of course, there’s all sorts of dirty business going on if someone can’t pay up and if someone runs away.”

At first, Doyle doesn’t get any credit from Dao Ming; she catches a whiff of loss and stalks off, uninterested. But after seeing a Chinese businessman throw himself off a Macau skyscraper, Doyle sees her again, and something sparks between the two lonely gamblers. “Dao Ming wants redemption, and so does Doyle,” Chen says. “They’ve both had a bad streak of luck, and they are both looking for inner peace and salvation, but going at it in very different ways.”

Doyle and Dao Ming spend a night together during the Festival of the Hungry Ghosts, where residents burn offerings for the dead. (The production shot during the tail end of the real festival.) When Doyle wakes up the next morning, Dao Ming is gone, and a mysterious number is written on his hand. Desperate for cash, he tries to shake down English ex-pat Adrian Lippett (Alex Jennings), only to learn that Lippett is the one who sold him out to Cynthia.

On his last legs, Doyle flees across the bay to Hong Kong, where he gorges himself on rich food and sees Dao Ming again — before he keels over, seemingly from a heart attack. He awakens to find himself on Dao Ming’s houseboat, in another reprieve from the chaos of the casino. “When he wakes up on the island, it’s suddenly so peaceful and quiet and silent, and it’s almost jarring, unsettling for him,” Berger says. “But he looks out and thinks, ‘Oh, this is actually beautiful.’ ”

For Doyle, Dao Ming becomes an island of calm in the roar of the casino’s ocean — a role Chen also served for Farrell. “There’s a simplicity to the scenes with Fala,” he says. “Even though there’s a lot going on, there’s not the chaos of the casino floors and the cards and the pandemonium and the screaming. It has a placidity to it that is really attractive to me after so much shouting and roaring and running and sweating.”

Doyle and Dao Ming open up to one another. He tells her about what he stole from the old woman, and she tells him about the money she stole from her parents: money she’s tried to repay, only to be rebuffed. She compares him to the festival’s hungry ghosts: creatures that will never be satisfied, no matter how much they eat or drink. And she tells him the number on his hand is a test.

A test he promptly fails. The next morning, Dao Ming is once again gone, and Doyle uses the number on his hand to open a lock that leads to his dream: a hidden stash of the money Dao Ming had tried to send back to her mother. Flush with cash once again, Doyle heads back to Macau to clean house. “Just for once, he wants to feel free of shame,” Farrell says. “I think ultimately that is what he wants, but he’s going about it the wrong way. He’s piling shame on top of shame on top of shame.”

Yes — and no. Doyle takes Dao Ming’s stash and immediately embarks on a winning streak for the ages, making enough money to clear his hotel debt, but not quite enough to get Cynthia and his old client off his back. On top of that, hotel management soon comes calling: Doyle is winning too much. They claim there’s a ghost attached to him, and he has to go. So Doyle tries a final gambit: one last massive bet. If he loses, it proves there’s no ghost. If he wins, he’ll leave Macau forever. “Doyle is completely guilt-ridden, completely lost in a vortex of lies and deceit and fraud, and he’s lost his way,” Berger says. “He’s lost his way, and he’s lost his peace.”

He finds an unlikely ally in Cynthia, who gives him one more chance to make his final bet instead of turning him over to the authorities. “There’s something about what happens to her when she arrives in Macau and when she comes up against Doyle that spins her off on a completely different direction,” Swinton says. “They are compatible in many ways. Doyle dares Blithe to acknowledge that she is faking it as much as he is.”

Doyle’s final game of baccarat is against a familiar face: Lippett, in disguise as a Monte Carlo prince. The two addict ex-pats square off, and Doyle walks away victorious. He pays off Cynthia and then some, telling her to “live a little.” Then he goes to find Dao Ming where they first met, at Grandma’s baccarat table.

Doyle resists Grandma’s final temptation, an offer of a bet with truly head-spinning odds. The money belongs to Dao Ming, and he plans to pay her back. But Macau has other ideas.

Dao Ming and Doyle’s connection was built on a shared loneliness. “They’re both lost,” Berger says. “He’s a lost soul and she’s a lost soul. She sees in his gaze that he’s someone who needs peace just as much as she needs peace. And that’s what they can give each other.” As Doyle learns from Grandma, Dao Ming found that peace on the night of the Festival of Hungry Ghosts — when she left Doyle the combination to her stash and drowned herself.

Berger hesitates to definitively state what happens to Dao Ming after that. “Everyone’s going to perceive the movie to their own liking,” he says. “For me, she dies during the movie.” In a way, the hotel manager was correct: Doyle does have a ghost guiding him from behind the scenes. “I do believe, in our story, she’s a ghost,” Berger continues. “[She’s] taking him through his life and guiding him. An act of redemption.”

As Doyle falls back through the memories of his time with Dao Ming, real or imagined, he begins to realize the depth of the chance he’s been given. “Dao Ming helps Doyle through this,” Berger says. “And he finds a center, the beginning of a path towards liberation. It’s also a liberation from falling into addiction. He’s able to shed it and just move past it and find some sort of peace that will allow him to hopefully lead a good life.”

The first step toward that life is to make an offering to Dao Ming, one he never would have considered days before: Doyle burns his winnings. “We start in a world of higher fountains and more colorful lights and bigger suites with pools and champagne and lobster and steak,” Berger says. “And we end with nothing, burning money in a temple, in a place of spirituality.”

It’s a moment that calls back to Doyle’s conversation with Dao Ming on the night of the festival, an act of selflessness and catharsis. “He does it, in the end, for her,” Berger says. “She saved him from his addiction, and he gives to her in the afterlife what she always needed in life.” We see Dao Ming’s face in a watery reflection, as Doyle, a new man, watches the fireworks bloom over Macau.

We get a taste of that new man during the credits of the film, where Berger flashes back to Doyle’s final meeting with Cynthia (real name: Betty). The ensuing dance sequence was originally meant to appear in the film itself, after Swinton’s character asks for a long-promised dance in the hotel ballroom.

But Berger felt it fit better after the film’s conclusion. “I don’t think Tilda intended to play her character as tempted and vulnerable until she met Colin,” he says. “She really became tempted to give into his promise of ‘Why don’t you live a different life?’ And that dance is an expression of that different life.”

The final sequence is a rare moment of pure joy in a film full of stress and sweat. “It mostly came from the relationship that I saw between Tilda and Colin,” Berger says. “It’s a candy for the audience, it releases you with joy and happiness, and it’s a dance, it’s a celebration of life. It’s a celebration of these two characters’ lives. And that they may have a new beginning.” We’ll bet on that.

Ballad of a Small Player is now streaming on Netflix.