The agriculture department has been focusing on coconut rhinoceros beetles on other Hawaiian islands, leaving Oʻahu largely to fend for itself.

Kimeona Kane drives his pickup truck around his neighborhood on the Windward side of Oʻahu pointing out dead and dying palm trees along the road. Nearby, the copious piles of mulch and rotting wood littering lots and private properties host the culprit: coconut rhinoceros beetles.

Kane has been trying to get a handle on the infestation for the past four years as chair of the Waimānalo Neighborhood Board, but he said his calls to the state’s reporting hotline, 643-PEST, went nowhere.

“I think at this point for Oʻahu, everyone’s kind of on their own,” he said.

As the Department of Agriculture and Biosecurity focuses on stopping the spread of coconut rhinoceros beetles on Hawaiʻi island and Moloka‘i residents fight to block it from reaching their shores, resources to deal with Oʻahu’s growing invasion have been diverted elsewhere.

Money allocated by the Legislature last session for the CRB Response Team offers some hope. According to the team’s Mike Melzer, the $500,000 will fund mitigation efforts on all of the islands, paying for things like pesticides, netting and biocontrol research.

The team recently returned from a trip to the Southern Hemisphere with samples of the Malaysian-borne nudivirus, which has shown promise in controlling beetle populations but may also have a negative impact on native species. While officials tap into limited resources to help all the islands, they’re also trying to empower local communities to fight the problem on their own.

Coconut rhinoceros beetles were first detected on O‘ahu in 2013 at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam to much alarm. The state agriculture department and its federal counterpart stepped up with a response plan.

But over the next 12 years, the situation on Oʻahu continued to decline, and the pests eventually spread to Kauaʻi and West Hawaiʻi island. The beetle has now been detected on all of the Main Hawaiian Islands except Moloka’i.

The state continues to treat trees on Oʻahu at beachfront parks and plant materials leaving the island, but offers little to no support for private land owners. Across the island, haggard looking coconut palms decorate roadways and golf courses as their hairlines recede, leaving only sparse strands on their crown. Some stand bald, having succumbed to their illness.

The dead trees create safety hazards for those who walk below them, yet no laws require businesses or home owners to deal with affected trees. Laws regulate the movement of green waste and mulch but don’t mandate management of the piles of rotting wood and biomaterial that litter the island.

Melzer and Jonathan Ho, plant quarantine branch manager for the agriculture department, both said they are optimistic that the newly funded biocontrol — the introduction of predators or disease to control a pest — will be a powerful tool.

Kane doesn’t share their optimism that it will make a difference in the state capital and most populous island.

“A lot of communities now are feeling the disappointing reality that Oʻahu has moved from being able to truly work towards eradication,” he said, “and are just now working on containment.”

A Smorgasbord

Karlo Tanjuakio and his partner moved to a gated community in West Oʻahu three years ago with big dreams of growing their own food. The house they chose sat on an acre with an easement allowing them to live in the community without joining the homeowners association so they could have more freedom to make decisions for their property. Tanjuakio said that it seemed perfect.

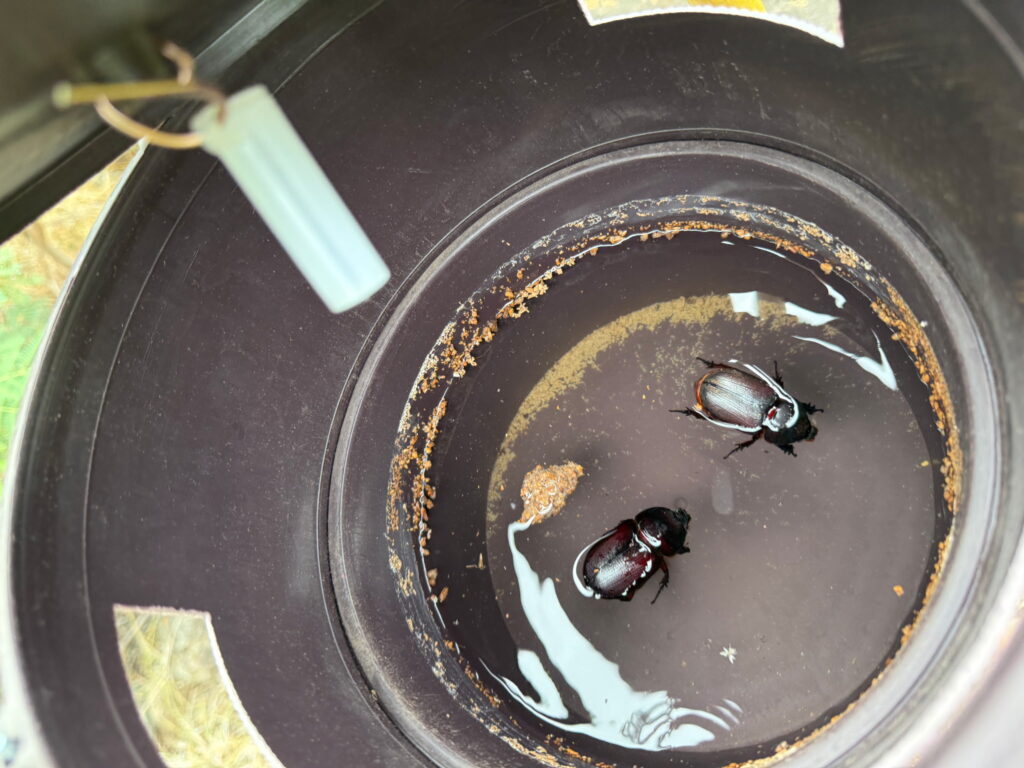

Then they started to find the carcasses of beetles in their compost. Tanjuakio said that his partner, the farmer in the family, began noticing signs of the beetles all throughout the valley.

“I had no idea what coconut rhinoceros beetles were,” he said.

The single black trap on the way to their house made them assume that the city was taking care of the issue. They soon learned they were wrong. Because the road to Mauna ‘Olu Estates is privately owned by the golf course in the valley below them, the state is not responsible, nor can it require the owners to deal with the trees.

Their palm trees didn’t last long. Tanjuakio said they really wanted to go the natural treatment route, but that wasn’t enough. After that failed, their landscaper told them the trees were too far gone and needed to be removed.

To their surprise, the beetles spread to other plants, like their papaya tree.

“A lot of people don’t realize that there’s hundreds of plants on the host plant list,” said Keith Weiser, deputy incident commander for the CRB Response Team. He said if palms are removed, the beetles will just move to one of the secondary host plants.

Inside the well-landscaped gated community, Tanjuakio said there were signs that the coconut rhinoceros beetles had spread to nearly all of the coconut palms.

One of Tanjuakio’s neighbors came to him when their palms started showing signs of infestation, but he doesn’t know if the rest of the neighborhood is even aware of the beetles. What is clear is that the infestation will persist if they cannot come together to address the issue as a community.

Risa Barcinas, an outreach associate with the CRB Response Team, said that is one of the services they have continued to offer Oʻahu residents: Neighborhoods can request trainings to learn about the beetles and design their own tailored response plans.

Fertile Ground

For Waimānalo, the situation is even more daunting. The wetter, more forested side of the island provides the ideal growing conditions for coconut rhinoceros beetles. The moisture and heat break down fallen leaves and downed trees to create natural breeding site material.

“Waimānalo is the best place for CRB, period,” Melzer said.

Driving around the area, it is obvious that agricultural land owners are trying to clean up their properties, though that, too, results in piles of materials. Some properties have spread mulch out so as to not have the large piles they were told propagate the beetles, according to Kane.

Ho, the Plant Quarantine Branch manager, said the beetles really only need about a trash bag worth of green waste or mulch to lay their larvae.

Even if you were to remove all of the mulch from Waimānalo — mulch that the farms need to grow their crops — the Waimānalo Forest Reserve would still have enough wild green waste materials to support the population indefinitely.

The community has discussed alternatives to mulch, like cardboard, but that would add another thing to farmers’ already lengthy list of issues to address.

Once again, community unification is both crucial and elusive.

For example, Kane said residents of the Saddle City neighborhood were very keen to protect their trees, but only if they could get funding to pay for the netting and boom truck. If not all of the neighboring properties participate, it would all be for nothing.

“You really have to have community buy-in when you have big properties like that,” Melzer said.

It’s not just about willingness to participate either. It can cost around $300 to treat one fully grown palm and up to $1,000 to have a tree removed. Netting to catch the bugs has to be acquired, put up and regularly cleaned. The out-of-pocket costs quickly escalate.

Beetles also are not the only invasive species Kane is attempting to deal with. With the coqui frogs proliferating throughout the forest preserve, he said he has largely turned his attention to catching frogs because it seems like a battle they are more likely to win.

“I feel like people have given up on the fight … this community has over a decade of trying to impact the issues around CRB,” Kane said, “How long are we gonna keep putting energy into something that’s not being met with the right resourcing?”

Going Viral

Hawaiʻi is not alone in its battle against the coconut rhinoceros beetle. The invasive bug has been making its way through Pacific Island nations since the 1940’s, according to the Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources.

Over the years, research has led affected nations to turn toward biocontrol. In their natural habitat, the beetles have predators and viruses that keep their population in check. But in Hawaiʻi, they have no natural predators, allowing them to run rampant.

In response, rather than introducing a predator, a technique used to control pest populations in the past, some nations are introducing viruses specific to the beetles.

A strain of virus discovered in Malaysia in the 1960’s has shown a lot of promise in controlling beetle populations in Southeast Asia and the South Pacific.

Biological control has a long history in Hawaiʻi. For example, the now common myna bird was originally introduced in 1866 to manage armyworms, the caterpillar stage of owl moths that attack crops. Myna have been criticized for causing problems for local seabirds, according to the American Bird Conservancy, and competed with now-extinct ‘ō‘ō, an endemic Hawaiian honeyeater, for nesting sites.

More recent examples include the use of parasitic wasps to control fruit flies on Hawaiʻi island, sea urchins released into Kāneʻohe Bay to control invasive seaweed, and the current campaign to make mosquitos infertile to save Hawaiʻi’s honeycreepers from avian malaria.

While in Palau, Melzer and his team got samples of the Malaysian-borne nudivirus for potential use on Hawaiʻi’s coconut rhinoceros beetles. Their team must make sure it is effective on the invasive beetles here without negatively impacting native species.

One cause for concern is a species of scarab beetle so rare that it only exists on Kauaʻi. Melzer’s team will be testing the native beetle’s sensitivity to the virus. If susceptible, it could spell death for that biocontrol initiative.

A large portion of the $500,000 allocated in Act 236 will fund the biocontrol research being done by Melzer’s lab, but a portion will go directly to community support. Melzer said that they plan to start distributing supplies as soon as the money hits their account.

Melzer said the team will be looking for the most equitable way to distribute mitigation methods that their lab know work to the communities that need them the most across all of the Main Hawaiian Islands.

“We’re calling it the circus,” Melzer said. “We’re taking this show on the road!”

CORRECTION: The status of the Hawaiian honeyeater was misstated and has been corrected.

Civil Beat’s coverage of climate change and the environment is supported by The Healy Foundation, the Marisla Fund of the Hawai‘i Community Foundation and the Frost Family Foundation and “Hawai‘i Grown” is funded in part by grants from the Stupski Foundation, Ulupono Fund at the Hawai‘i Community Foundation and the Frost Family Foundation.

Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

Journalism that matters

Civil Beat is a nonprofit, reader-supported newsroom based in Hawaiʻi. When you give, your donation is combined with gifts from thousands of your fellow readers, and together you help power the strongest team of investigative journalists in the state.

Every little bit helps. Will you join us?

About the Author

-

Leilani Combs is a reporting intern for Civil Beat. You can reach her by email at lcombs@civilbeat.org.

Leilani Combs is a reporting intern for Civil Beat. You can reach her by email at lcombs@civilbeat.org.