'It still has the ability to shock': Why 'masterpiece' Wuthering Heights is so misunderstood

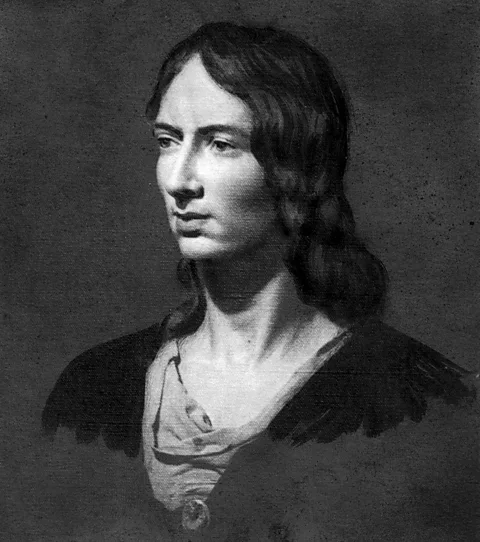

Alamy

AlamyEver since it was published in the mid-19th Century, Emily Brontë's tale of passionate love and ruthless revenge has captivated fans and confounded critics in equal measure.

Authored by one "Ellis Bell", Wuthering Heights was met with rather mixed reviews when it was first published in 1847. Some were scathing, horrified by its "brutal cruelty" and portrayal of a "semi-savage love". Others acknowledged the book's "power and cleverness", "its delineation forcible and truthful". Many said it was simply "strange".

Despite the popularity of gothic fiction at the time, it's perhaps unsurprising that Wuthering Heights shocked readers in the 19th Century, a time of strict moral scrutiny. "People did not know what to do with this book, because it has no clear moral angle," says Clare O'Callaghan, senior professor of Victorian literature at Loughborough University in the UK, and the author of Emily Brontë Reappraised.

Three years after the novel was published, Charlotte Brontë revealed the true identity of its author – Ellis Bell was not in fact a man, but a pen name for her younger sister, Emily Brontë. Charlotte argued that critics had failed to do Emily's work justice, "The immature but very real powers revealed in Wuthering Heights were scarcely recognised; its import and nature were misunderstood."

A gothic tale of two families set on the wild Yorkshire moors, Wuthering Heights went on to become a genre-defining classic – and yet, Charlotte's words still ring true.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNow, Saltburn director Emerald Fennell is poised to reveal her version of the story, with a film released on 13 February, starring Australian actors Margot Robbie as Catherine Earnshaw and Jacob Elordi as Heathcliff. Perhaps partly in response to the various controversies preceding her film – around the age and ethnicity of the lead actors, the erotically charged scenes and inauthentic costumes shown in the trailer – Fennell added quotation marks to its title, stating that she is not actually adapting the novel, but making her version of it, because the story is too "dense, complicated and difficult". Could she be right?

And just why has this "strange" but captivating novel puzzled fans, readers and critics from the beginning?

A tale of passion and revenge

Fennell isn't wrong about the book's complex nature. Its non-linear, multi-layered structure and multiple narrators can be mind-boggling at first. Why does everyone have the same name? How many Cathys and Catherines and Lintons and Heathcliffs and Linton Heathcliffs can there possibly be in 300-odd pages?

Wuthering Heights is effectively a story-within-a-story. Jumping between the past and present, and spanning around 30 years, it is told by Lockwood, Heathcliff's tenant, and Ellen Dean, a maid at two houses called Thrushcross Grange and Wuthering Heights. Both narrators are unreliable.

Lockwood, a gentleman from London with a superiority complex, serves as a nosey outsider and a vessel for the reader to uncover secrets from the past. Nelly, the revealer of said secrets, tells the story from a seemingly perfect memory. She controls the narrative and often interferes when perhaps she shouldn't – her emotional attachments to certain characters, and judgment of others, shine through.

Warner Bros

Warner BrosFennell has spoken of how she was captivated by the novel when she first read it as a teenager. Her film uses the tagline "the greatest love story of all time", but the greatest revenge story of all time might be more apt. Of course, there is undeniable romantic passion in the story: "Whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same; and Linton's is as different as a moonbeam from lightning, or frost from fire." But some readers may have latched onto this, while forgetting what ensues afterwards.

It quickly becomes clear that Heathcliff is more of a tortured anti-hero than a romantic one. Catherine is challenging too – she is melodramatic and spiteful. Their unbreakable bond, while spirited and everlasting, is ill-fated – and their unending misery creates a generational cycle of abuse and destruction begging to be broken.

The structure of Wuthering Heights cleverly plays into these themes of passion and revenge. The first edition was divided into two volumes, which could be perceived as the generational divide – the first focusing on Catherine and Heathcliff, the second focusing on their children. Brontë draws on our sympathy for Heathcliff in the first volume. Upon his arrival at the Heights as an orphaned young boy, he is othered, a "ragged, black-haired child… a dark-skinned gipsy in aspect". Catherine even spits on him.

Later, he is physically abused by his drunkard adoptive brother Hindley Earnshaw, who treats him as a servant. Throughout, he is referred to as "dirty". His only solace is Catherine, with whom he roams the wild moors. But even then, despite her declaration, "I am Heathcliff… he is more myself than I am," and partly due to a misheard conversation, she marries the wealthy Edgar Linton of Thrushcross Grange.

Heathcliff's revenge on Edgar and Catherine intensifies in the second half of the novel, after the latter's death. Brontë sorely tests any sympathy readers might have had for Heathcliff, as his monstrous tyranny reigns. He physically and psychologically abuses his wife (and Catherine's sister-in-law) Isabella through vile acts like hanging her dog.

Warner Bros

Warner BrosHe also abuses the family's children. Hindley's son Hareton is forced to work as a servant just as Heathcliff was as a young boy. He kidnaps Cathy Linton, Catherine and Edgar's daughter, forcing her to marry his son, Linton Heathcliff, to secure ownership of Thrushcross Grange. Every action is deliberate, calculated and vengeful.

The novel's complex legacy

Some film and TV adaptations have skipped the second half of Wuthering Heights entirely, presumably because of its savagery and complexity – William Wyler's 1939 Oscar-winner ends shortly after Catherine's death, her ghost and Heathcliff wandering the moors. Robert Fuest's 1970 film starring Timothy Dalton also ends with her death, as does Andrea Arnold's 2011 film, which dedicates most of the screen time to the younger Catherine and Heathcliff.

But her death comes halfway through the novel and therefore many adaptations have missed out a further 18 years or so of plot, softening the ending and sanitising its darkest parts. A few have attempted to cover the whole story – including the BBC's 1967 series, which inspired Kate Bush to write her 1978 hit. But it's the BBC's 1978 mini-series (aided by its five-hour running time), which is held up as being the most faithful to the whole text.

Ignoring the latter part of the book "doesn't work", says Claire O'Callaghan. "I think love and vengeance are the engines of the book, and that's what so great about it… there's no boundary to the depths to which [Heathcliff] will go to, to make people pay," says O'Callaghan.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHeathcliff lives a life of torment and uncontainable grief, but inflicts that suffering on everyone around him and feels no remorse in doing so. By not righting his wrongs, and letting him die without further punishment, O'Callaghan says, Brontë poses more complex questions to the reader, rather than giving them answers: What is love? Does the marriage system work? What are the limits of violence?

That's part of the complex legacy of the novel. "Popular culture tends to tell us it's this great romance… when [readers] are encountering it for the first time, that jars, because the book is so different. It still has the ability to shock, and I think, like the Victorians, we're still grappling with how to define it and what to do with it," O'Callaghan says.

Another popular misconception of the novel is that it's unremittingly bleak, when, at times, it's quite funny. Nelly and Zillah, the two servants, are major gossips. Linton Heathcliff is a mopey, sickly and bratty child, who provokes an eye roll from the reader. And when you can understand what the farm servant Joseph is saying through his thick Yorkshire dialect, he is often a witty cynic, who never has anything nice to say. When Catherine falls ill after searching for Heathcliff in the rain, he snarkily croaks, "Running after t'lads, as usual?"

More like this:

• Why Heathcliff and literature's greatest love story are toxic

• Why readers are wrong about Mr Darcy

• Why Frankenstein is so misunderstood

Lockwood's snootiness is amusing, too. "He is like a character from a Jane Austen novel who's walked into a Brontë world, and that, for me, is hilarious," says O'Callaghan. "If you read this book and take it as a kind of gothic satire to some extent, it's a completely different book. And I think that's one of the things, though. People take it very, very seriously, don't they? They're absolutely convinced that these are real characters, rather than this gothic, over-the-topness."

Emily Brontë never saw the success of her only novel, but we know that she read initial reviews. Her writing desk is on display at the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth, and it contains five clippings of Wuthering Heights reviews, which were largely negative. She died at the age of 30 from tuberculosis, around a year after Wuthering Heights was published. Behind her she leaves a masterpiece.

Whether you are a fierce lover or loather of Brontë's deeply flawed characters, the harrowing and unsettling plot and the toxic romance, Wuthering Heights has possessed its legions of fans throughout history – "driven us mad", you could say. We can be sure that Fennell's interpretation will not be the last. Whether anyone can do this book justice on screen, however, is a whole other question.

Hopefully, at least, we can all agree with one anonymous critic, who reviewed Wuthering Heights in January 1848. "It is impossible to begin and not finish it," they said, "and quite as impossible to lay it aside afterwards and say nothing about it."

Wuthering Heights is released on 13 February.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.