'Operation Rockall successfully completed': The tiny island seized by Britain to foil the USSR

MOD

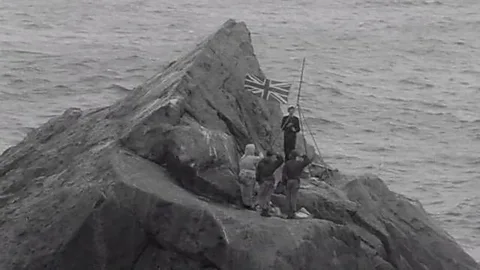

MODSeventy years ago, the British Empire claimed its last piece of territory – a bleak and uninhabited island, 260 miles (420km) west of Scotland's Outer Hebrides. In 1955, a Royal Navy commander told the BBC about securing Rockall, which remains the site of rival claims even today.

In 1956, the British naturalist James Fisher described Rockall as "the most isolated small rock in the oceans of the world" – and understandably so. The island of Rockall is almost unimaginably remote, an 11-hour boat ride from Scotland's Outer Hebrides, and it is also tiny, measuring a mere 82ft (25m) wide, with a summit only 56ft (17m) above sea level. Most of it consists of bare, near-vertical granite, with just one small patch measuring 11ft by 4ft (3.5m by 1.3m) which is level enough to stand on. As insignificant as this jagged stone outcrop might appear, though, Queen Elizabeth II authorised the annexation of Rockall on 14 September 1955, instructing the Royal Navy to "take possession of the island on our behalf".

Rockall's exact position was first charted by Royal Navy surveyor Captain ATE Vidal in 1831, but it was not until 1949 that Rockall became more widely known, after its name was given to one of the sea areas on BBC Radio's Shipping Forecast. It was around this time that the UK government recognised Rockall's strategic significance. As the Cold War intensified and Nato and Soviet submarines regularly patrolled the North Atlantic, securing Rockall was viewed as key to controlling sea space. Moreover, 230 miles (370km) east, on South Uist in the Outer Hebrides, the UK had established its first test site for US-made guided nuclear missiles. Nato documents, declassified in 1970, revealed the government's fear that "hostile agents" would install themselves on Rockall to spy on the results of the tests.

A Royal Navy survey ship, HMS Vidal, reached the rock on 15 September 1955, but it would be another three days before high winds subsided enough to allow a helicopter to winch three Royal Marines on to it, along with James Fisher, a civilian scientist. There, the men planted the Union flag and formally claimed the islet for Britain. "I had an instruction from Her Majesty to annexe the island of Rockall in her name," Commander Richard Connell, captain of HMS Vidal, told the BBC reporter Neville Barker shortly after the landing. "We sent a signal to the Admiralty saying, 'Operation Rockall successfully completed.' I was never so glad to send any signal in my life."

Fisher was tasked with taking rock samples from the islet for study by the British Geological Society. Rockall was formed from the remains of an eroded volcano, and the granite found there was "apparently unique", Fisher told the BBC. Years later, geologists studying Rockall granite would identify a new mineral – bazirite – that had yet to be found anywhere else in the world.

In History

In History is a series which uses the BBC's unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today. Sign up to the accompanying weekly newsletter.

In 1955, annexation of Rockall was about ensuring national security. But within a few decades, the government became more concerned with securing rights to Rockall's fish-rich waters, and the potentially vast oil reserves on the seabed. Ireland, Iceland and Denmark (acting on behalf of the Danish Faroe Islands) had begun staking rival claims to these lucrative waters. Keen to cement British ownership, Parliament voted to formally incorporate Rockall into the UK in 1972, making it part of Scotland's Western Isles.

However, no other nation recognised the UK's claim. A further blow came in 1982 when the UN Convention of the Seas was ratified, effectively preventing uninhabited rocks without an economy from being used as the basis for territorial claims. This meant that ownership of Rockall would no longer be decisive in the battle for oil rights to the seabed below.

Activists and adventurers on Rockall

It was a patriotic desire to reaffirm Britain's claim to the islet that prompted former SAS soldier Tom McClean to set up camp on Rockall in 1985. He spent 40 days and nights there in a bid to prove the rock could sustain human habitation, living in what he described as a "wooden box" and becoming the first person known to reside on Rockall. When the UK first annexed the islet in 1955, "no other country was interested," McClean told the BBC's World at One. "It went on for about 10, 20 years and then oil started popping up and everybody was interested in Rockall."

McClean would not be the only person to reside on Rockall with the aim of making a political statement. In June 1997, three Greenpeace activists landed by helicopter to claim Rockall as the capital of an entirely new micro-nation – "the Global State of Waveland" – in a stunt to protest against the government's granting of mining licences in the region. Greenpeace said it wanted to "borrow" the islet until it was "freed from the threat of development", offering citizenship of Waveland to anyone prepared to take their pledge of allegiance.

More like this:

• The CIA spy plane shot down over Russia in 1960

• The first men to conquer Everest's 'death zone'

• The greatest sailing rescue ever made

Activists spent a total of 42 days on the islet, beating McClean's record. Shortly afterwards, the UK finally accepted that Rockall was, legally, a "rock", when it acceded to the UN Convention of the Seas in July 1997. Overnight, the UK ceded fishing and mining rights to a 200-mile radius area around Rockall, prompting protests from fishermen angry at the loss of bountiful fishing grounds. Huge swathes of sea were defined as "international waters" and opened to negotiations between interested parties – debates that still rumble on today.

The Scottish Labour Peer Lord Kennet, a former seaman, said of Rockall: "There can be no place more desolate, more despairing, more awful to see in the world." But that hasn't stopped the lucrative waters around the islet being fought over by several nations – and the bleak outcrop continues to lure adventurers. One of them, Nick Hancock, survived on the rock for 45 days in 2014, setting a new world record. However, the unforgiving conditions have spelt disaster for others. In 2023, Army veteran Cam Cameron had to be rescued halfway through his own world-record attempt, after rough weather damaged his kit. "I don't think there's anything as terrifying as being on that rock – 300 miles from people, 200 miles from the nearest bit of land," he told the BBC's Sunday Show. "It was a lonely time."

--

For more stories and never-before-published radio scripts to your inbox, sign up to the In History newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.