We’ve all heard of the “privacy paradox.”

People insist that privacy matters to them, expressing a strong desire to protect their personal data. Yet they readily share information, either for the sake of convenience or in exchange for a minimal reward.

Their words seem to belie their actions.

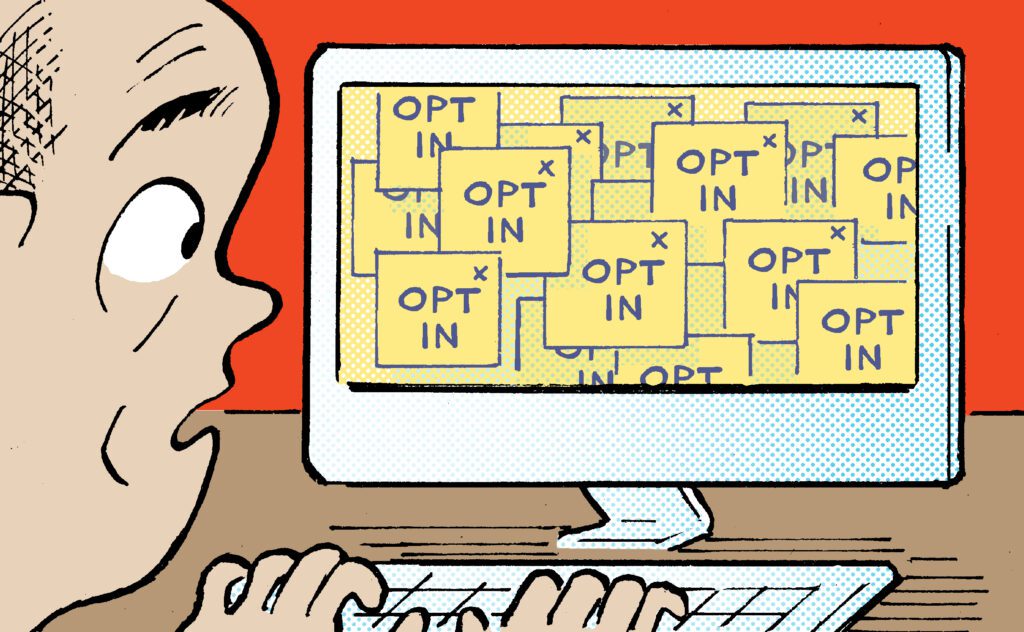

But there’s a reason for this contradiction. It’s not that people don’t care about their privacy; it’s that the systems designed to protect them are so convoluted and abstract they’d make Rube Goldberg blush.

Tom Kemp, the newly appointed executive director of the California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA), rejects the notion that people are simply apathetic and hypocritical.

“We fundamentally believe that exercising privacy rights should be easy,” he said during a virtual event hosted by privacy management platform DataGrail earlier this month.

Opt-outs “shouldn’t be buried in legalese,” and they “shouldn’t be hidden and covered up with dark patterns,” said Kemp, who was appointed in March after Ashkan Soltani, the agency’s first executive director, left in January.

No tricks, just fair treatment

In September of last year, the CPPA – which, just by the by, now also informally goes by the nickname “CalPrivacy,” because California is so awash in bewildering privacy-related acronyms (CCPA, CPPA, CPRA) – issued an enforcement advisory on dark patterns.

The advisory warns businesses that they should avoid manipulative and confusing user interface designs that make it difficult for consumers to exercise their privacy rights, which is prohibited under the California Consumer Privacy Act.

Enforcement advisories are little gifts from regulatory agencies to the business community. They serve as early warning signs of which practices might soon attract enforcement and penalties.

AdExchanger Daily

Get our editors’ roundup delivered to your inbox every weekday.

Daily Roundup

It should therefore have surprised no one when, in July, the California attorney general’s office, which shares enforcement responsibility with the CPPA for the CCPA, (makes sense why CPPA started going by “CalPrivacy,” good grief) levied a $1.55 million fine against digital health publisher Healthline – the largest CCPA fine to date – for, among other things, using deceptive consent banners and failing to honor opt-out requests. Both are classic examples of dark patterns.

Shortly after, in September, CalPrivacy issued its largest fine to date – $1.35 million – against farming supply retailer Tractor Supply for multiple infractions, including (again) failing to honor opt-out requests, failing to support the Global Privacy Control and making inadequate privacy disclosures.

“The law and the regulations make it quite clear,” Kemp said. “As technology evolves, privacy protections must evolve with it, and that’s why we’re really focused on enabling consumers to operationalize their privacy and make it useful.”

Back to the so-called privacy paradox, it’s simply not true that people aren’t really concerned about privacy.

In 2020, for example, 9.3 million Californians voted for Prop 24, the ballot initiative that enacted the CPRA, which isn’t wildly less than the number of people who voted during the last gubernatorial election in the state in 2022.

And now, CalPrivacy receives, on average, around 150 complaints from consumers a week, which translates to thousands of consumer complaints every year.

“The problem,” Kemp said, “is that [opting out is] too difficult and [people] get frustrated, so we’re trying to break that frustration loop.”

To that end, California passed the Delete Act, which includes a mandate for CalPrivacy to create a simple, centralized mechanism that consumers can use to submit a single deletion request to all registered data brokers at once.

CalPrivacy has been building that tool, called DROP – short for Delete Request and Opt-Out Platform – since the Delete Act passed in 2023. It’s set to launch on Jan. 1, 2026, just a few months from now. Starting on Aug. 1, 2026, data brokers will be required to check the platform every 45 days to process these requests and delete matching data from their systems.

“It’s the ability to exercise privacy at scale for consumers,” Kemp said. “‘Please delete my information and opt me out moving forward.’”

🙏 Thanks for reading! As always, feel free to drop me a line at allison@adexchanger.com with any comments or feedback. Also, happy Halloween! And regards from the sassiest cat alive.