2019 · BAND 109 · HEFT 2

ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR

ASSYRIOLOGIE

UND VORDERASIATISCHE ARCHÄOLOGIE

HERAUSGEGEBEN VON

Walther Sallaberger, München

IN VERBINDUNG MIT

Antoine Cavigneaux, Genf

Grant Frame, Philadelphia

Theo van den Hout, Chicago

Adelheid Otto, München

Angemeldet | anmar_aaf@yahoo.com

Heruntergeladen am | 16.11.19 14:10

� Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 2019 | Band 109 | Heft 2

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Abhandlungen Kenan Işık*

The Irrigation Canal Stele of the Urartian King Argišti I

Hans Neumann Recently Discovered in Erciş/Salmanağa,

Karl Hecker 25. 7. 1933 – 22. 4. 2017 123 North of Lake Van 204

Khalid Salim Ismael and Shaymaa Waleed Abdulrahman Nicolò Marchetti, Abbas Al-Hussainy, Giacomo Benati,

New Texts from the Iraq Museum on Šulgi-mudaḫ Giampaolo Luglio, Giulia Scazzosi, Marco Valeri and

and Šara-dān 126 Federico Zaina

The Rise of Urbanized Landscapes in Mesopotamia:

Hossein Badamchi The QADIS Integrated Survey Results and

According to the Laws Established by the Gods! the Interpretation of Multi-Layered Historical

A Re-Examination of MDP 23, 321+322 145 Landscapes 214

Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez Juan Aguilar und Peter A. Miglus*

Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I: Das dritte und vierte Relief von Gundük 238

Two Babylonian Classics 155

Sebastian Fink and Simo Parpola Buchbesprechungen

The Hunter and the Asses: A Neo-Assyrian Paean

Glorifying Shalmaneser III 177 Anne Goddeeris: The Old Babylonian Legal and

Administrative Texts in the Hilprecht Collection Jena

Alwin Kloekhorst* and Willemijn Waal (Zsombor Földi) 247

A Hittite Scribal Tradition Predating the Tablet

Collections of Ḫattuša? 189 Nele Diekmann: Talbot’s Tools. Notizbücher als

Denklabor eines viktorianischen Keilschriftforschers

(Martin Worthington) 269

Angemeldet | anmar_aaf@yahoo.com

Heruntergeladen am | 16.11.19 14:10

� Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 2019; 109(2): 155–176

Abhandlung

Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil* and Enrique Jiménez

Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I:

Two Babylonian Classics

https://doi.org/10.1515/za-2019-0012

Abstract: Publication and edition of two tablets from the library in the Ebabbar Temple of Sippar, a manuscript of

the ‘Babylonian Poem of the Righteous Sufferer’ (Ludlul bēl nēmeqi) Tablet III, and a manuscript of the long prayer to

Marduk ‘Furious Lord’ (also known as ‘Marduk 1’).

To Werner R. Mayer

on his 80t h birthday

The eighth campaign of Baghdad University at Sippar that will resume the publication of this veritable treasure

(1985/1986) unearthed one of the most spectacular dis- chest of Babylonian literature.2

coveries of twentieth century Near Eastern archaeology: The two tablets edited here, IM 124581 (No. 1) and IM

a collection of over 300 cuneiform tablets and hundreds 124504 (No. 2), were both found in Niche 3 C of Room 355

of fragments on the very shelves where they were kept in of the Ebabbar Temple. This niche yielded a large number

antiquity. The circumstances in the Middle East during the of tablets and fragments, most of them badly eroded.

past decades have hindered the publication of the Library, Among the tablets from this niche there is a manuscript of

to such an extent that today, thirty years after its discov- ‘Enūma Anu Enlil’ XX (IM 124485 = al Rawi/George 2006)

ery, less than one tenth of the tablets has been published.1 and manuscripts of ‘Enūma eliš’ I and VII, scheduled to

The present article is the first of a series of contributions appear in the second installment of the present series.

The first tablet presented here is a manuscript of the

‘Babylonian Poem of the Righteous Sufferer’ (Ludlul bēl

nēmeqi), the second a manuscript of the long prayer to

Marduk ‘Furious Lord’ (also known as ‘Marduk 1’). Both

Article note: The tablets are published with the kind permission

texts are ‘Babylonian classics’ in the strictest sense of the

of the College of Arts (University of Baghdad) and the State Board

of Antiquities and Heritage. Note the abbreviation CTL 1 = George,

word: transmitted for generations,3 they were staples of

A. R./J. Taniguchi (2019): Cuneiform texts from the folios of W. G. first-millennium school education.4 Their longevity and

Lambert. Part one. MC 24. University Park. their role in teaching students how to read and write cunei-

form meant that they exerted a powerful influence over

1 36 of the 358 IM numbers catalogued were published as of 2004 Mesopotamian belles lettres, and were often emulated in

(Hilgert 2004), and only four additional tablets have been published

devotional poetry and cited in letters and commentaries.

since: IM 124485 (al Rawi/George 2006), IM 132506 (Fadhil/Hilgert

2007), IM 132543 (Fadhil/Hilgert 2008), and IM 132516 (Fadhil/Hilgert

2011). A preliminary catalogue of the Sippar Library was prepared by

Hilgert (2004), using the old excavation photos, and has been used 2 Some tablets from the Sippar Library have deteriorated over the

here with the author’s permission. A new catalogue, based on the years. The tablets published here have been conserved in the Iraq Mu-

study of the original tablets in the Iraqi Museum, is currently in seum by C. Gütschow, as part of a conservation project begun in 2018

preparation. with funding from the Humboldt Foundation in the framework of the

‘electronic Babylonian Literature’ project (Sofja Kovalevskaja Award).

*Corresponding authors: Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil, Department of 3 ‘Marduk 1’ was copied from the late Old Babylonian period until

Archaeology, College of Arts, The University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Arsacid times, ‘Ludlul’ from the Kassite period until the second half

Iraq; E-Mail: anmar.fadhil@coart.uobaghdad.edu.iq of the first millennium BCE.

Enrique Jiménez, Institut für Assyriologie und Hethitologie, 4 Over twenty elementary school tablets with extracts of either ‘Ludlul’

Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Munich, Germany; and ‘Marduk 1’ are known from Babylon and Sippar, ranking second in

E-Mail: enrique.jimenez@lmu.de number of school manuscripts only behind the ‘Epic of Creation’.

�156 Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I

Both texts have a similar structure: a framing poetic hymn 9. [ištânu eṭlu atar ši]-⸢kit⸣-t[a]

to Marduk encloses a wisdom section in which the god’s 10. [minâti šurruḫ lu-bu]-⸢uš-tu₄⸣ ud-du-u[ḫ]

punishing and redemptory powers are exemplified. In this

sense, ‘Ludlul’ can be seen as a Kassite expansion of the lit- 11. [aššu ina munatti īdûšu] gat-tu₄ zuq-qúr

erary form epitomized by the two great prayers to Marduk. 12. [melamma ḫalip labiš pu-ul-ḫa-t]i :

13. i-ru-ba-am-ma it-ta!(é)-ziz elī(ugu)-⸢ia⸣

14. [āmuršū-ma iḫḫamû] šīrū(uzumeš)-ú-a

I A Manuscript of Ludlul bēl

nēmeqi III 15. [šū-ma (?) bēlka] iš-pur-an-ni

16. [o x-mi šumruṣu li-qa]-⸢a⸣ šu-lum-šú

The manuscript IM 124581 (Sippar 8, 114/2277) once con-

tained the entire third tablet of Ludlul bēl nēmeqi, of which 17. [ú?-ram-ma a-tam-ma]-⸢a⸣ a-na mu-kil re-⸢ši⸣-ia

currently twenty-five lines (20 %) survive.5 The beginning 18. [ša šarrum-mi išpuru] a-me-lu [ma]n-nu

of the third chapter of ‘Ludlul’ recounts the dreams that

announce the main character’s (Šubši-mešrê-Šakkan) 19. [iqūlū-ma ul i-pu-l]a-an-ni

redemption. The most important contribution of the new m[a-a]m-man

tablet is the complete restoration of the first dream. In it, 20. [šūt išmûninni a-n]a ri-pi-it-tu iṣ-ṣab-t[u]

a young man of great stature presents himself as a mes-

senger of the sufferer’s “lord.” The young man does not 21. [ašnī-ma šu]-na-at a-⸢na⸣-[aṭ-ṭal]

state which “lord” sent him,6 nor need he do so, for Šubši- 22. [ina šunat a]ṭ-ṭu-lu!(ur) mu-š[i-t]i-⸢ia⸣

mešrê-Šakkan knows that the “lord” can only be his king,

Nazi-Maruttaš. The news that the messenger brings is 23. [ištânu ramku] na-áš mê(ameš) šip-ti

reassuring indeed: the “wretched one” (scil. Šubši-mešrê- 24. [bīna mu]l-lil-lu₄ ta-mi-iḫ rit-tuš-šúsup.ras.

Šakkan) should “expect” (quʼʼu) either his recovery or the

king’s salutation, depending on the understanding of the 25. [làl-úr-ali]m-ma āšip(lúmaš.maš)

word šulumšu (see below commentary on l. 16). The news Nippur(nibruki!)

frightens the sufferer’s attendants, who were privy to the 26. [ana ubbubī-k]a iš-pur-an-nisup.ras.

king’s anger with Šubši-mešrê-Šakkan, and causes them

to flee (ll. 19–20). 27. [mê našû elī(ug]u)-ia id-dì(ti)

28. [šipat balāṭi] ⸢id-da⸣-a ⸢ú⸣-maš-ši-iʼ zu-um-ri

⁂

29. [ašluš-ma šutta a-n]a-aṭ-ṭal

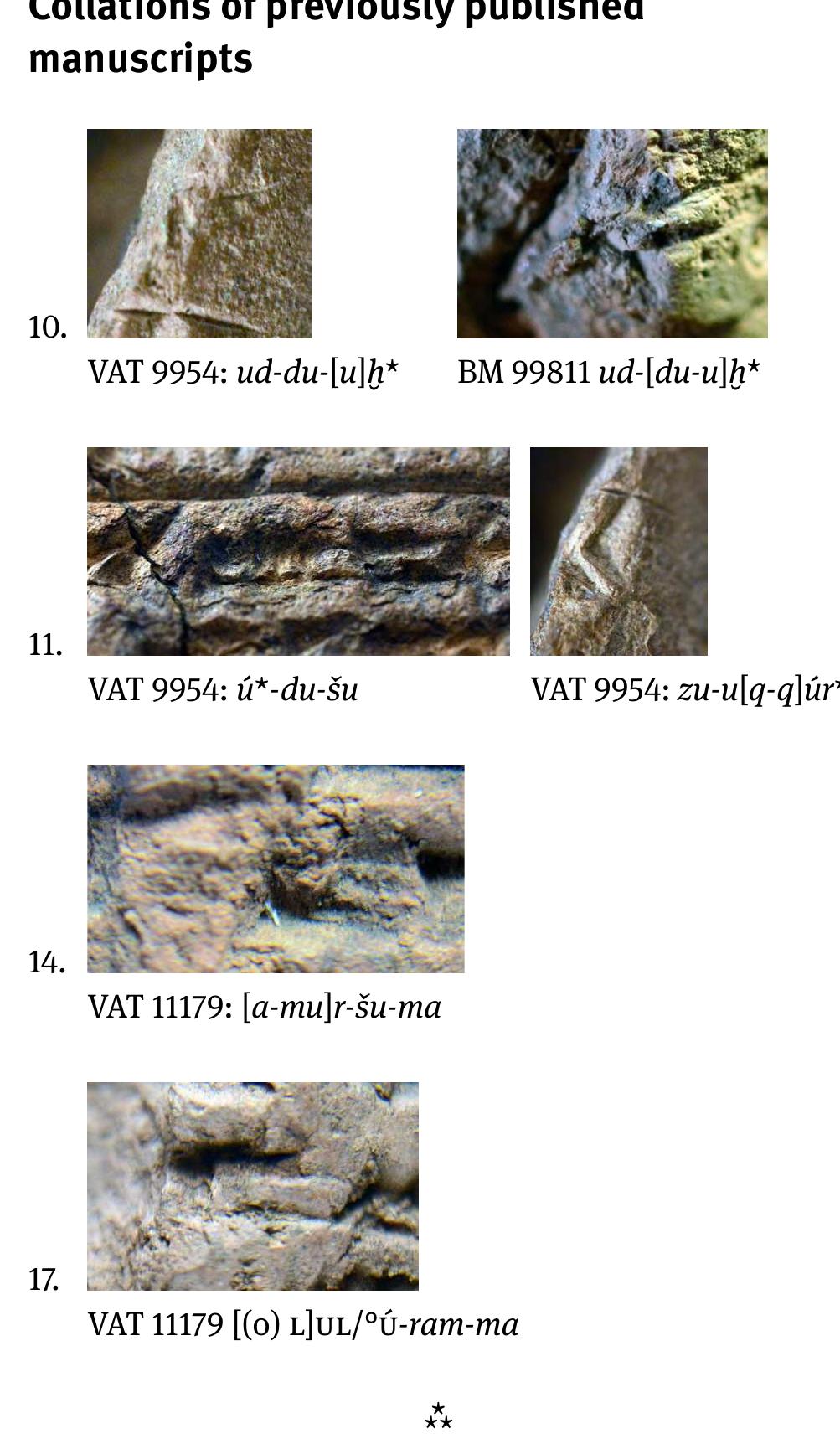

The recovery of the passage has prompted the re-exami- 30. [ina šunat aṭṭulu] mu-ši-ti-ia

nation of its already known manuscripts. BM 99811 was

collated in the British Museum in February 2018, the man- 31. [ištêt ardatu ba-nu]-⸢ú⸣ ⸢zi⸣-mu-šú

uscripts VAT 9954 and VAT 11179 in the Vorderasiatisches 32. [nesîš la ṭuḫ-ḫa-t]i ⸢i-liš⸣ ma[š]-⸢lat⸣

Museum in April 2018. Important new collations have been

obtained, and closeups of individual signs are reproduced 33. […] x x […]

with permission of the Trustees of the British Museum and 34. […] x […]

of Lutz Martin, Acting Director of the Vorderasiatisches

(rest broken)

Museum. The manuscript Si.55 has been examined on

the basis of the Ph[oto] K[onstantinopel] 395, courtesy of

Selim F. Adalı.

5 An important manuscript of ‘Ludlul’ I from the Sippar Library,

IM 132669 (Sippar 415/351) was published by George/al Rawi (1998,

187–201). It was found in Niche 1 D, together with, among others, a

manuscript of the ‘Šamaš Hymn’ (IM 132673, unpubl.).

6 “Your lord” has been interpreted as Marduk by Lenzi (2012, xxii

and 61 fn. 92) and Oshima (2014, 275 f.).

� Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I 157

10

!

15

20

25

30

1 cm

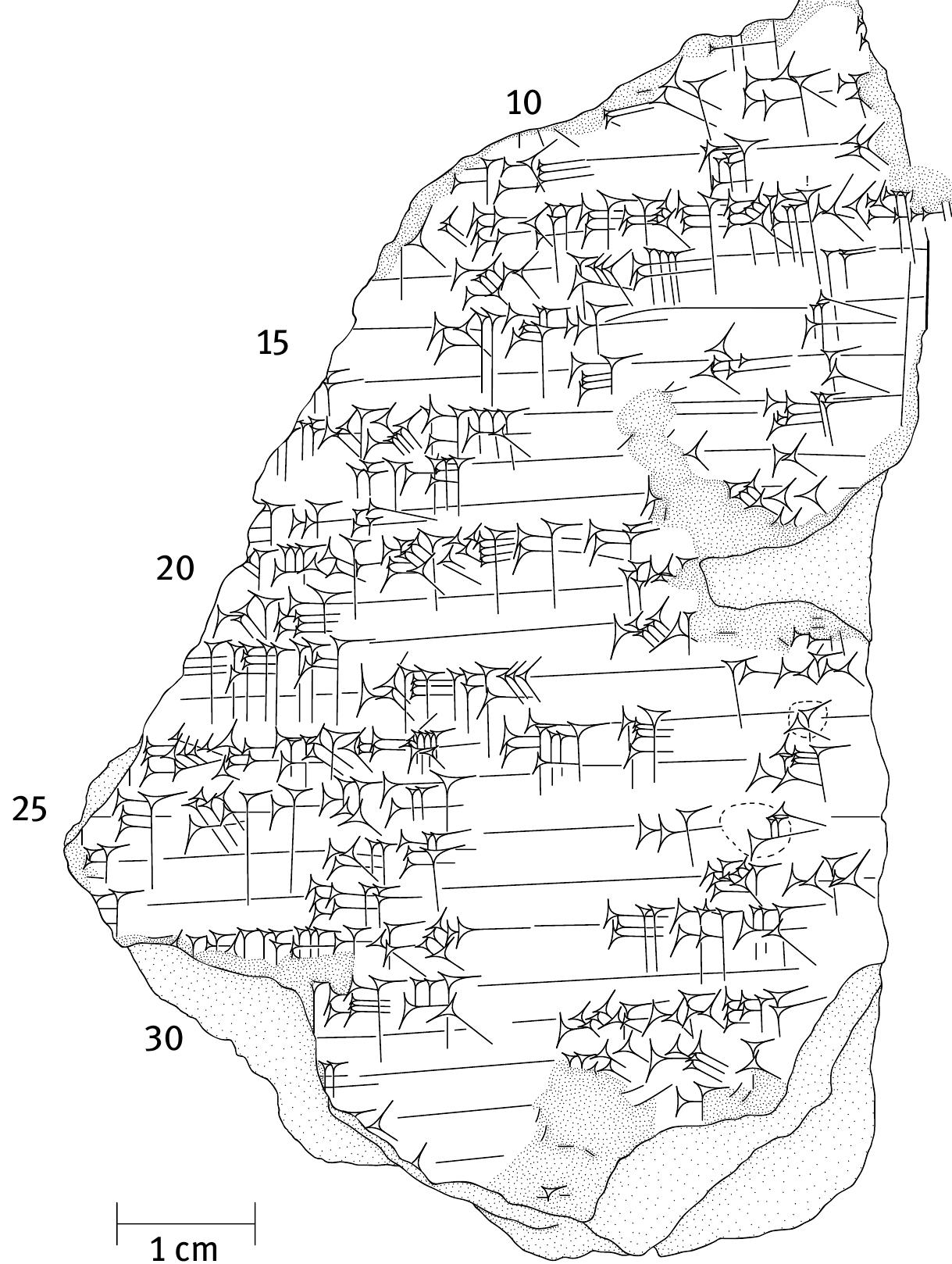

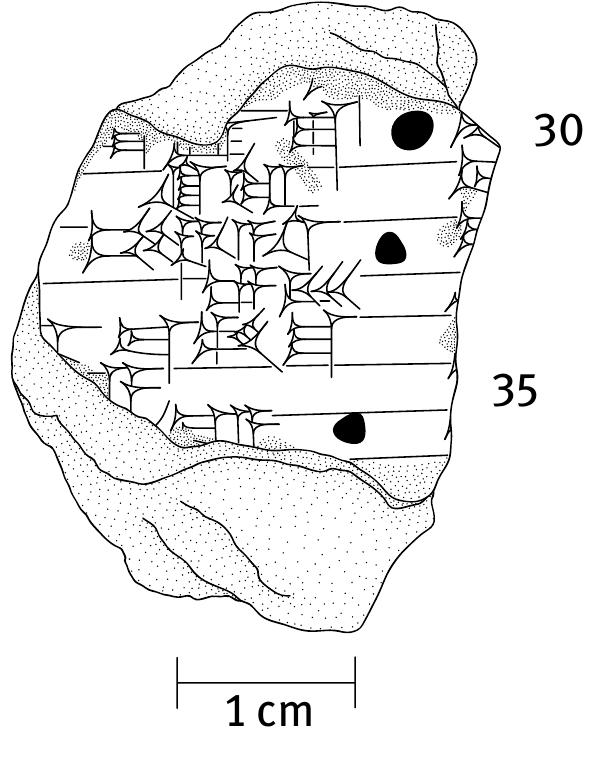

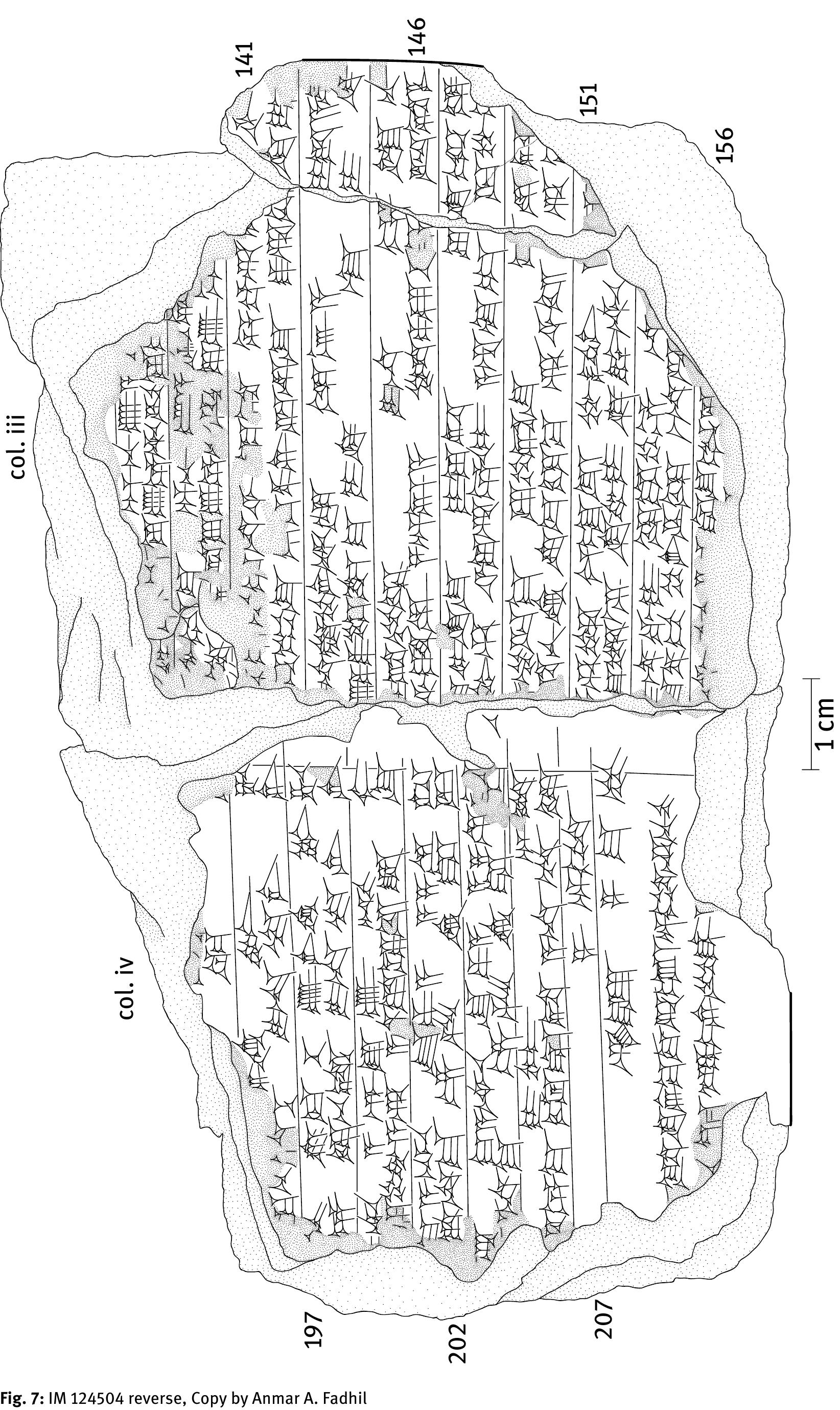

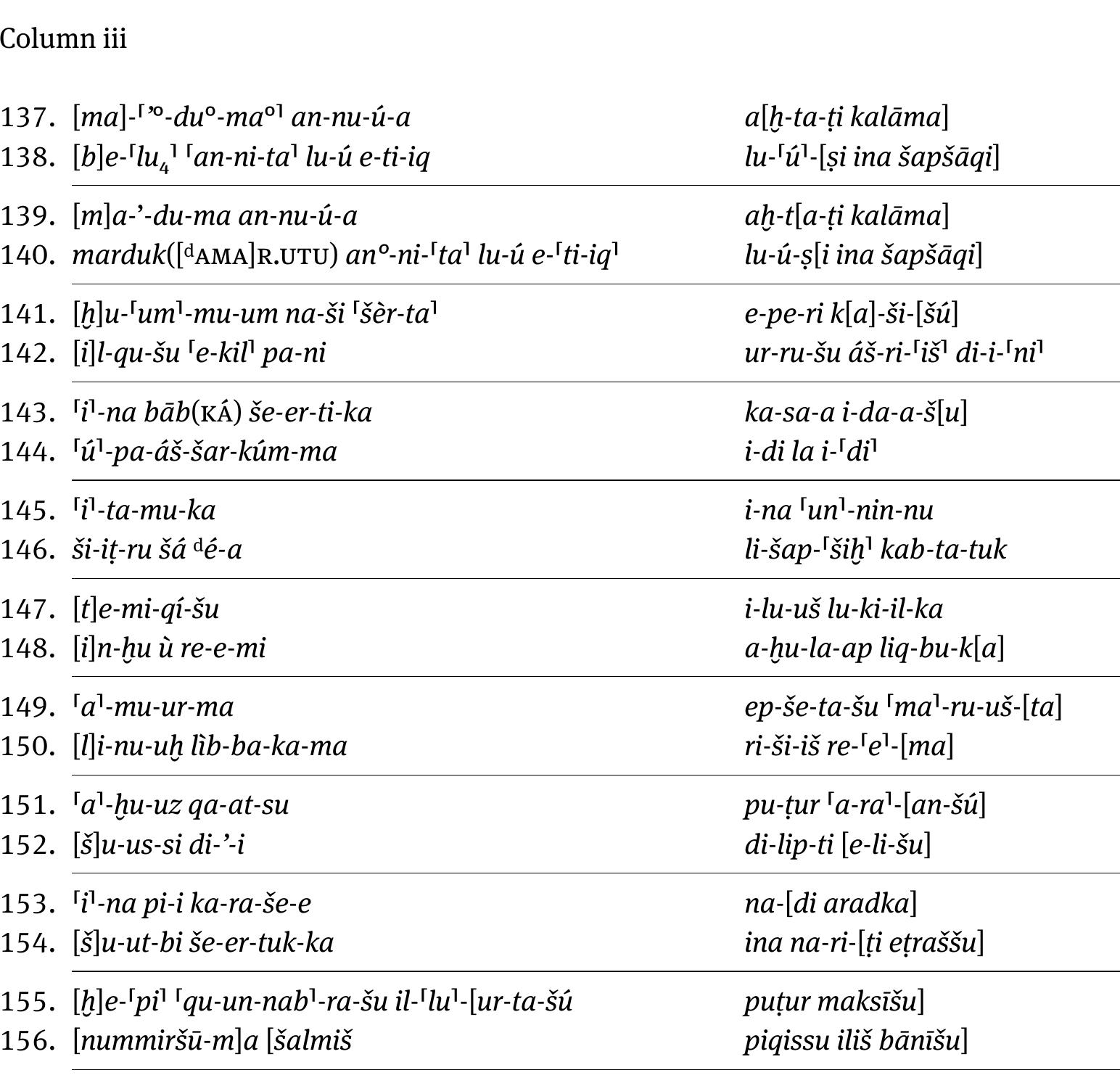

Fig. 1: IM 124581, Copy by Anmar A. Fadhil

Translation

(9) [(There was) one lad, surpassing in f]or[m],

[Of splendid appearance], swat[hed in a clo]ak.

[Because I descried him half awake], he was of tremendous stature,

(12) [Clad in radiance, dressed in aw]e.

He entered and stood above me,

[When I sa]w him, my body [was paralyzed].

(15) [He (said): “Your lord] has sent me,

“Saying: ‘[Let the wretched one exp]ect his recovery!’”

[I woke up and address]ed my attendants,

(18) Saying: “Who is the man [whom the king has sent?”]

[They kept silent], none of them [answe]red,

[Those who heard me], took to their heels.

(21) I s[aw a second dr]eam,

[In the dream I] saw this night,

[(There was) a priest], carrying consecrated water,

�158 Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I

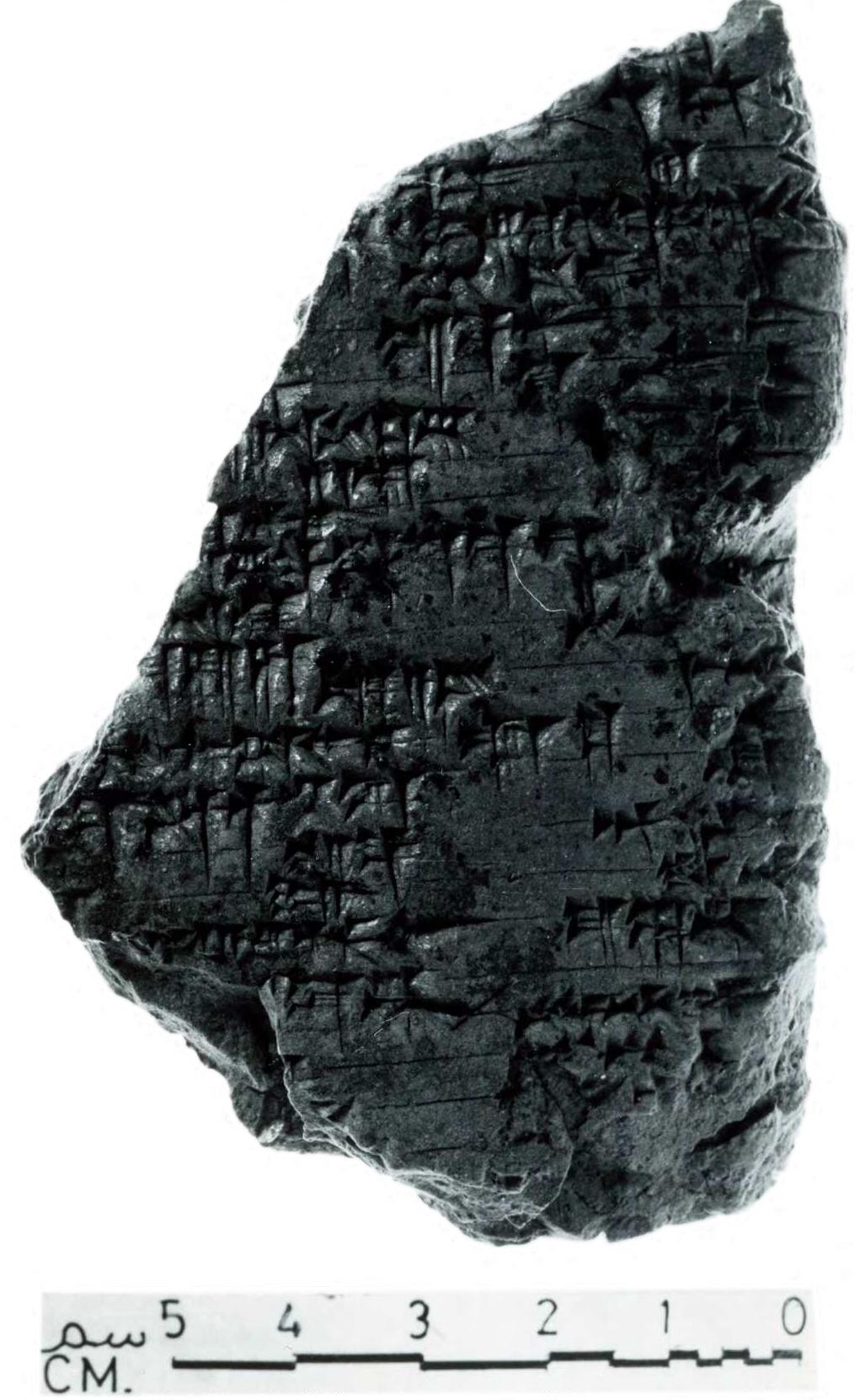

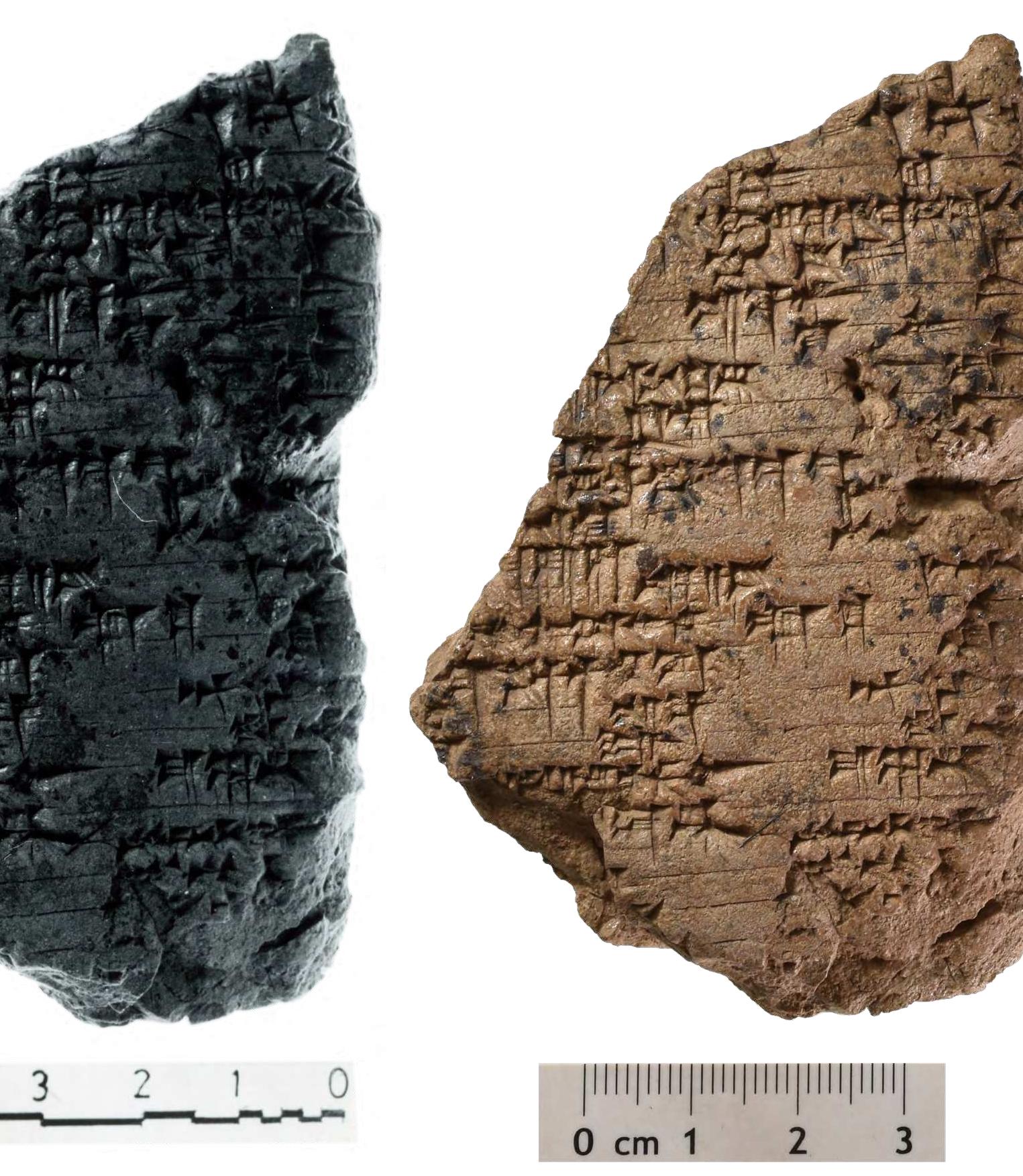

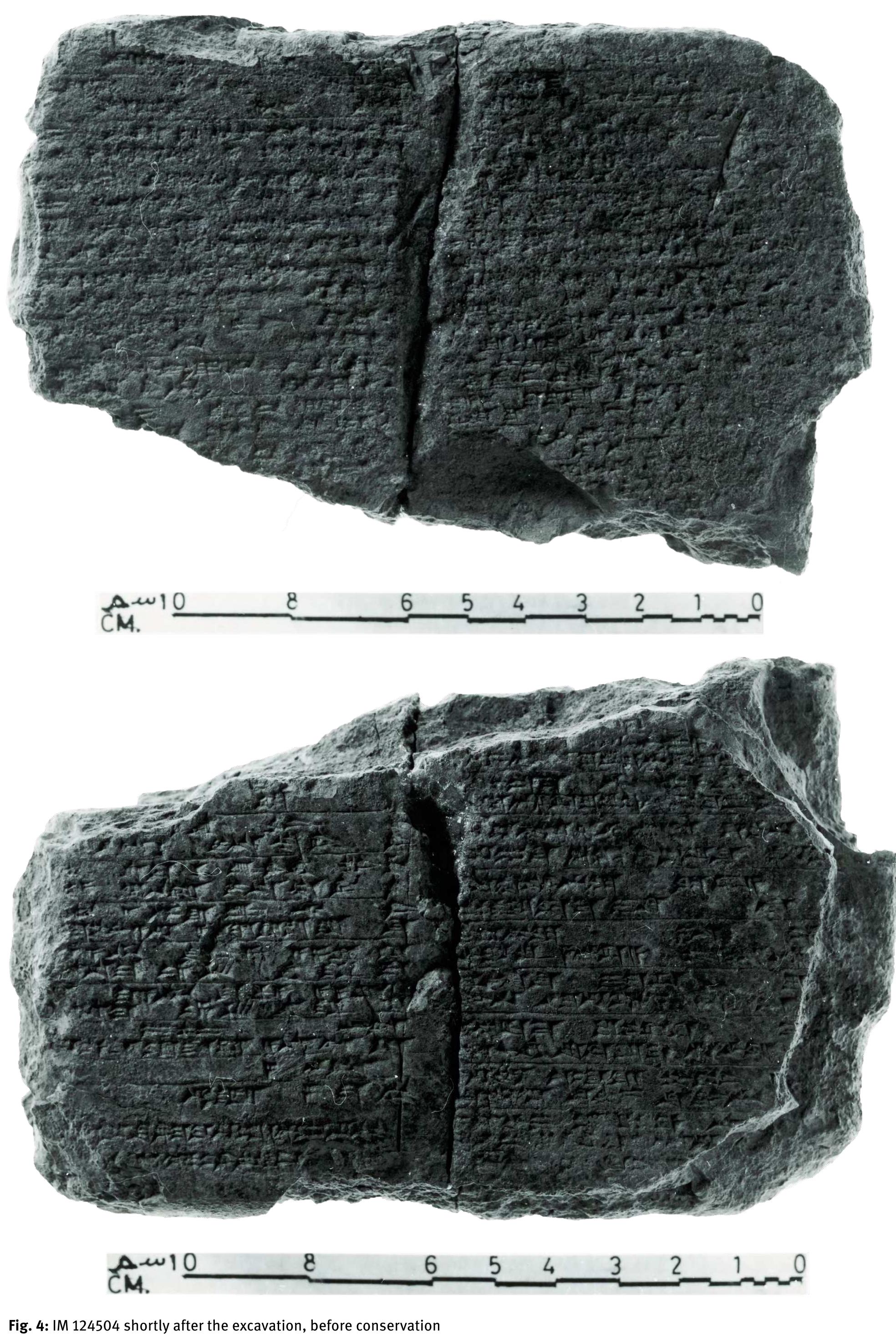

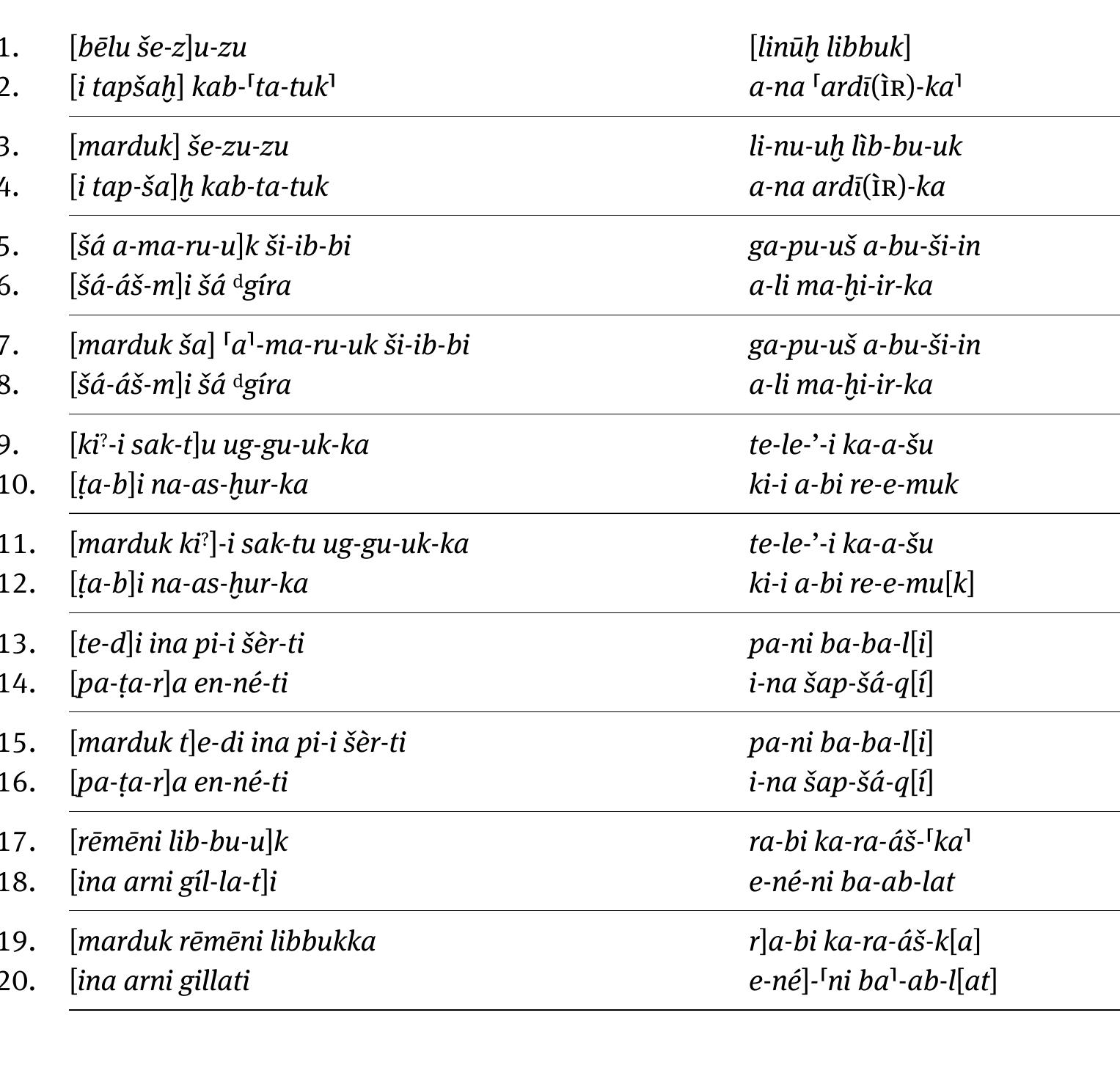

Fig. 2: IM 124581 shortly after the excavation Fig. 3: IM 124581 after conservation (March 2018)

(24) Holding in his hand the [pu]rifying tamarisk.

“[Lalurali]ma, the exorcist of Nippur,

“Has sent me over [to cleanse you].”

(27) He sprinkled [on] me [the water he was carrying],

And cast [a reviving spell] whilst rubbing my body.

[I s]aw [a third dream],

(30) [In the dream I saw] this night,

[(There was) one maiden], her countenance [was fair],

[Standing aloof, ak]in to a god,

(33) […] … […]

⁂

� Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I 159

:الترجمة 1455a). On munattu as “period of wakefulness or drows-

، ال َمثي َل لشَكلِ ِه،ك فت ًى َ كانَ هنال (٩)

ing” particularly suited for prophetic dreams, see George

. كا ِمالً بِ َملبَ ِس ِه،رائعا ً ب َمظهَ ِر ِه (2015, 4) and Streck (2017, 601).

،ض ِخمةَ ُ فَقَد كانَت قاَمتَه،صحو ِة َ وألنَّني لَ َمحتَهُ َوقتَ ال The end of the line in VAT 9954 (BWL pl. 12) should

ً

. ُمتَأزرا بالرُعب،س برّاقة َ ُِمرتَديا ً مالب (١٢)

now be read as zu-u[q-q]úr*,8 previous attempts to restore

،ي َو َوقَفَ أمامي َّ َد َخ َل عَل it (e. g. zu-u[m-mu-u] by von Soden 1990, 127 followed by

.َوحالما َرأيتَهُ ُش َّل َجسدي Annus/Lenzi 2010, 23; sú-u[q-q]u by Oshima 2014, 275 and

،ك أر َسلني َ سي ُد:فَقا َل (١٥)

pl. xxxiii) should now be abandoned.

!المريض يتأ َم ُل ِشفا ًء َ ِ :ًقائال

َدع The sequence of dreams is strongly reminiscent of

، َالحاضرين ِ ً خاطبا

ِ ضت ُم ُ َفَنَه Gudea’s dreams in his ‘Cylinder A’: there, “one man, sur-

َم ِن ال َر ُج َل الذي أر َسلَهُ ال َملك؟:ًقائال (١٨)

passing like the sky” (l ú d i š - à m a n - g i n₇ r i - b a - n i ,

، َولَ ْم يجبْ أحداً ِمنهم،فظّلوا صامتين Cyl A iv 14 [Edzard 1997, 71]), later revealed as Ningirsu, is

. َولّوا على أعقابِهم،هؤالء الذينَ َس َمعوني followed by “one lady” (m u n u s d i š - à m , ibid. iv 23),

،ًرأيت حلما ً ثانيا ُ لقد (٢١)

revealed to be Nissaba.

،ك اللَيل ِة َ الحلم الذي رأيتَهُ في تِل ِ وفي

،ً يَح ِم ُل ماءاً نقيا، ٌكانَ هُنالك كا ِهن 14. [a-mu]r-šu-ma looks possible on VAT 11179 (BWL pl. 74,

.ًماسكا ً بِيد ِه أثَالً طا ِهرا ِ (٢٤)

see adjoining close-up).

،َّز ُم َمدينَ ِة نُفّر ِ ع م

ُ ،اللوالريما ُإنَّه

.ََوقَد أر َسلني ألطَ ِه ُرك 15. As noted by Mayer (2014b, 278), the restoration

،ُفَر ّشني بالما ِء الذي كانَ يَح ِملَه (٢٧)

[iq-bi]-ma at the beginning of the line (adopted by von

ً.ي تَعزيما َّ وبَينما ه َو يَدَهنَ ِجسمي ألقى عل Soden 1990, 127 and, following him, Annus/Lenzi 2010, 23

،ًرأيت حلما ً ثالثا ُ لقد and Oshima 2014, 414) is unlikely because of the lack of

،ك الليل ِة َ وفي الحل َم الذي رأيتَهُ في تِل (٣٠)

space in VAT 11179 (BWL pl. 74). Lambert’s (1960a, 344)

،ٌ َمال ِم َحها َجميلة،ٌك عَذراء َ كانَ هُنال restoration [um?]-ma is more likely, but the use of umma

، قريبةً من أح ِد االلِهة،الناس َ عن

ِ َل ٍ تَقِفُ بِ َمعز for introducing direct speech is unparalleled in ‘Ludlul’.

]…[ … ]…[ (٣٣)

The restoration adopted here is based on the fact that

šū-ma in ‘Ludlul’ I 25 is in clear parallelism with iqabbī-ma

in ‘Ludlul’ I 23.

Philological Commentary

16. The very damaged traces of the line in VAT 9954 (BWL

10. The fragment shows that the end of the line should pl. 12) seem, upon collation, compatible with a reading [o

be read as udduḫ, and the old reading ud-du-uš should o (o)-m]a ⸢šum-⸢r[u]-ṣ°u? l°i-qa⸥-°a⸥ š[u-lum-šú], whence

be abandoned. The two known manuscripts of this line the tentative reading li-qa-a (< quʼʼû) adopted here.

read: ud-du-[u]ḫ* (VAT 9954 = BWL pl. 12, collated) and If the reading of the verb is correct, šulumšu could be

ud-[du-u]ḫ* (BM 99811 [CTL 1, 62] collated). edēḫu D stative understood either as the wretched man’s “recovery” or the

is normally used with a plural adjacent accusative (Kou- king’s “salutation.” Only the former sense is attested in

wenberg 1997, 151 f.), whence the present understanding ‘Ludlul’ (in III 68: [uṭṭe]ḫâm-ma tâšu | ša balāṭi u šulmi,

as “to be completely covered.” Compare also ‘Bulluṭsa-ra- “he brought near his spell of life and health”),9 but the

bi’s Gula Hymn’ 160 (Lambert 1967, 126, restored with meaning “salutation” seems also suitable in the context

83-1-18, 430 [CTL 1, 57]): ḫīpū inbūʼa ṣapša udduḫāku, “my of a message.

allure is compelling, I am swathed in a dress.”

11. The first verb in BM 55481 (Oshima 2014, pl. xi; CTL

1, 156) is i-du-šú, whereas in VAT 9954 (BWL pl. 12) it is 8 Note that the second radical of the verb zaqāru is frequently written

ú*7-du-šu (i. e., an Assyrianism, GAG § 106q). “To recog- elsewhere in first-millennium tablets with the sign kur. See e. g. zu-

nize” somebody is usually edû D, not G (CAD I/J, 31b; AHw. qúr in Sm.656+ r 17′ (SAA 4, 48), zuq-qúr*-tu₄ and zu-qúr* in K.2235+

o 6 (Koch 2005, 91), zuq-qúr in K.8909+ l. 1 (SAA 4, 340+), and zu-uq-

qúr* in two LB manuscripts of ‘Udugḫul’ XII 14 (Geller 2016, 402, both

7 Not šid-du-šu, as mistakenly copied in KAR 175 and repeated in instances should be corrected in Geller’s edition).

BWL pl. 12 (Lambert 1960a, 48), and adopted by all subsequent inter- 9 Collated: Si.55 (PhK 396): ⸢šá⸣ b[a]-⸢la⸣-⸢ṭu* u š[ul-mi] // BM 68435

preters (e. g. von Soden 1990, 127, Annus/Lenzi 2010, 23, and Oshima (Gesche 2001, 558 = Oshima 2014, pl. xi = CTL 1, 158): šá din u šu-lum.

2014, 275). See the adjoining close-up photograph. Compare te-e šul-mu ù ba-la-ṭu in BM 54633+ obv. 8 (unpubl.).

�160 Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I

17–18. mukīl rēšīya is a plural, as indicated by the plural 23. On mê šipti, literally “the water of incantation,” see

verbs in ll. 19–20: on plural genitive chains with the regens PSD A/1, 13.

in singular, see GAG § 64l and Mayer (1990, 452; 2015, 191).

The restoration of the first verb remains a problem. 27. Sense requires the verb id-ti to stem from nadû,

VAT 11179 (BWL pl. 74) was read by Lambert (1960a, 345) however strange the reading dì might be. The reading

as [o n]ar-ram-ma (and, similarly, Oshima 2014, 276 as it-[bu-uk] (Borger 1964, 51b; von Soden 1990, 127; Annus/

[p]uḫ-ram-ma); but as [š]u!-tab!-ram-ma by von Soden Lenzi 2010, 23) should be abandoned.

(1990, 127 note ad loc.; and, following him, Annus/Lenzi

2010, 23).10 The newly recovered context prevents the 32. The second word has previously been read as la-a[b-

reconstruction of an imperative here, so only Lambert’s š]á!?-ti (von Soden 1990, 128 ad loc., followed by Annus/

reading seems possible. Upon examination of the tablet, Lenzi 2010, 24) and k[a-pi]š-ti (Oshima 2014, 281 and 415,

the readings [lu]l and also °ú appear to be most likely (see but see Lenzi 2017, 185b). Neither solution is satisfactory.

the adjoining close-up), whereas x.tab is more difficult. Both go against the traces in Si.55; the second, more-

One would expect here the sequence PRETERITE-ma over, yields no good sense, and the adverb nišiš, “like a

DURATIVE, well attested in dream narratives, e. g. in ‘SB human”, would be a hapax legomenon (CAD N/2, 280b;

Gilgameš’ IV 95: [i]tbē-ma ītammâ ana ibrīšu, “(Gilgameš) AHw. 796a).15

woke up talking to his friend.”11 The best candidate for The interpretation adopted here is easier to reconcile

the context is the relatively rare verb êru, “to wake up,” with the traces.16 The first word would then be the rela-

a verb previously known only in the G stative and infini- tively common adverb né-siš, “from afar”, instead of the

tive (see Mayer 2016, 208) and perhaps in Št (AHw. 1554b, hapax ni-šiš.17 nesîš lā ṭeḫû, “not approaching from afar”,

GAG § 106b). The verb, derived from an etymon ʿwr (cp. is a well-attested idiom (CAD N/2, 184a; AHw. 781b), and

Hebrew ʿwr, “to wake up”), is now also attested in a finite “standing aloof” is a decidedly divine behavior (see Mayer

form in a Middle Babylonian text: naši šittī a-⸢we⸣-er bītam 1980, 312–314).

adūl, “my sleep taken away, I became awake and roamed The new reading of the signs as ṭuḫ⸥-⸤ḫa-ti has

the house” (Wasserman 2016, 133 no. 11 obv 4 and ibid. enabled the identification of the small fragment BM 39523

137).12 Two restorations seem possible, neither of them (80-11-12, 1409) as belonging to this section of ‘Ludlul’. The

without difficulties: (1) [a-n]ar-ram-ma, a hitherto unat- fragment, published here by permission of the Trustees of

tested, irregular N stem of êru, “to be awake,”13 and (2) the British Museum, was identified in a notebook of trans-

([a]-)°ú-ram-ma, a G (?) stem. The latter seems more likely, literations generously made available by Mark Geller for

but only the discovery of new duplicates will settle the the “electronic Babylonian Literature” project, and has

question. been copied by Fadhil on the basis of photographs kindly

taken by Jon Taylor. BM 39523 certainly belongs to the

22 = 30. On the syntax of the line, see George (2003, 802), same tablet as BM 55481 (82-7-4, 54) and confirms the new

who notes that “mušītīya is genitive and one must presume reading ṭuḫḫât, but adds little else to the understanding

an idiomatic ellipsis of ina.” Another possibility would be of the text.

to take ina šunat … mušītīya as a genitive chain interrupted

by the insertion of the line’s verb, in which case the verb

should be indicative.14 On possessive pronouns with time

expressions, see Mayer (2016, 206).

10 The traces in VAT 9954 are compatible with [o o-a]m-ma. 15 The word was first interpreted as nišiš, “like a human,” appar-

11 For this and other similar expressions, see Mayer (2007, 124–127). ently by Ebeling (1926, 278: “Wie Menschen eine sch[öne] Jungfrau,

12 The form a-⸢we⸣-er is taken as awʾēr (i. e. aʾēr with a glide) by Was- mit schönen Gesi[chtszügen]”)

serman (2016, 137). The expected form would be aʾūr. 16 A reading ṭuḫ⸥-⸤ḫa-ti in Si.55 fits both Thompson’s (Thompson

13 Other verbs with the meaning “to be awake,” such as dalāpu, 1910, pl. iii) and Lambert’s copy (BWL pl. 13), as well as the traces

have an ingressive N stem. visible in the old photograph (PhK 395). Compare the old reading bi?

14 Note that ina šunat mušītīya alone appears in ‘Gilgameš MB Ur’ in Thompson 1910, 19 (followed by Ball 1922, 23).

l. 62 (George 2003, 300), compare ina šāt mušītīya in ‘Gilgameš OB’ 17 The writing né-ši-iš in VAT 9954 r 1 is explicable as a confusion in

II 3 (George 2003, 172). On genitive chains interrupted by a verb, see sibilants typical of Assyrian documents. For more cases of confusion,

Mayer (2017, 231): tāmarātu našû lalêki. see Hämeen-Anttila 2000, 9 f. and Jiménez/Adalı 2015, 155 fn. 4

� Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I 161

who brings suffering but also salvation, the two succes-

sive topics of the poem:18 every couplet of the initial hymn

30 contains a miniature summary of the entire composition.

After the hymn, Šubši-mešrê-Šakkan’s troubles begin

in I 41–42: “After the day my Lord punished me / And the

hero Marduk became angry with me.” Marduk’s anger

causes, first, the anger of other divine beings19 (I 41–54),

35 discovered by divination professionals (I 52), and even-

tually provokes the anger of the king (I 55 ff.). The god’s

anger, from the poem’s perspective, triggers the king’s dis-

favor. The sequence is therefore Marduk → Divine interme-

diaries → Human intermediaries (diviners) → King.20

As we now learn from the new fragment, the absolu-

1 cm tion takes place in much the same way: in the first dream

(III 9–20), the king announces his forthcoming mercy; in

the second (III 21–28), the sender is an exorcist; the third (III

Collations of previously published 29–38) brings a message perhaps from other divine beings;

manuscripts and the fourth dream (III 39–46) is Marduk’s harbinger. The

sequence is therefore: King → Human intermediaries (exor-

cist) → Divine intermediaries → Marduk.21 The sequence

can be described as a Newton’s cradle, in which Marduk’s

anger, transmitted first through divine and then through

human intermediaries, moves the king to anger. Redemp-

10. tion, in turn, is swung back first by the king’s appeasement,

VAT 9954: ud-du-[u]ḫ* BM 99811 ud-[du-u]ḫ* which culminates, first through human and then through

divine intermediaries, in the god’s forgiveness.

Marduk’s anger comes to an end in a similar manner

to which it began: in III 50–51, “After my Lord’s heart was

st[illed] / And the mind of merciful Marduk was cal[med].”

‘Ludlul’ I 40 to III 51 is therefore a ring composition.

11.

VAT 9954: ú*-du-šu VAT 9954: zu-u[q-q]úr* The god’s anger thus triggers the king’s — since both

‘Ludlul’’s king, the Kassite monarch Nazi-Maruttaš (r.

ca. 1307–1282 BCE), and its main character, the governor

Šubši-mešrê-Šakkan, are historical figures, it is tempting

to regard the entire poem as a theological elaboration of a

historical event, namely the anger of the king with one of

14. his officials.22 The extremely artful language of the poem,

VAT 11179: [a-mu]r-šu-ma perceivable for instance in the strings of never-repeating

18 See the studies by Lambert (1995, 32–34) and Piccin/Worthington

(2015).

19 Mesopotamian gods other than Marduk are named throughout

‘Ludlul’ with the merismus “the god and the goddess,” as in I 43–44.

17. 20 As noted by Lenzi (2012, 59–63), the description of ‘Ludlul’ as an

VAT 11179 [(o) l]ul/°ú-ram-ma “anti-institutional” manifesto by Pongratz-Leisten (2010) is entirely

inaccurate: the text conveys a decidedly pro-institutional message.

21 Zgoll (2006, 285) speaks of a “aufsteigende Hierarchie” of the

⁂

gods mentioned in the dream narrative (but cf. Lenzi 2012, 61 fn. 92).

22 As pointed out by Lambert (1995, 34): “it is surely likely that an

The first chapter of ‘Ludlul’ begins with a programmatic historical figure chosen to be the speaker in this long monologue

hymn (I 1–40) in which Marduk is described as the one would be chosen because something of the kind had actually hap-

�162 Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I

synonyms (I 81–92), turned it into a classic of Babylonian 61–68, Oshima 2011, 216–274), and the ‘Nabû Hymn’ (von

literature, emulated by poets and cited by exegetes and Soden 1971), with which it displays some similarities.

correspondents.23 Furthermore, it ensured the immortal- ‘Marduk 1’ is, however, the only one whose composition

ity both of its author and of Nazi-Maruttaš, a king who can be dated to the Old Babylonian period. The structure

would otherwise have little claim to fame (Frazer 2013). of the text is, as stated above, similar to that of ‘Ludlul’: a

A text concerning a legal dispute involving Šubši-mešrê- hymnic section with the structure ABAB opens the poem

Šakkan and Nazi-Maruttaš, and known from first-millen- (ll. 1–40), followed by a long wisdom section (ll. 41–145)

nium Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian manuscripts,24 with snippets of narration, which is followed by an impe-

might have been transmitted as the prose version of the trative section (ll. 146–194) and culminates in a section that

same event narrated in ‘Ludlul’, and might perhaps speak celebrates the god’s appeasement and the redemption of

in favor of its historicity. his devotee (ll. 195–206). The hymn contains 206 lines, but

it is probable that it originally had 200 verses, like other

“great hymns,” since some of its lines are expansions that

break the poetic structure and should probably be excised:

II A Manuscript of ‘Furious Lord’ thus, line 61 is an expanded repetition of 60, and 144–145

(‘Marduk 1’) was originally perhaps a single, four-foot verse.

Some manuscripts of the poem, in particular those

The tablet IM 124504 (Sippar 8, 038/2201)25 preserves around from Nineveh and Sippar, divide the text into sections of

half of the literary prayer to Marduk entitled ‘Furious Lord, two lines each by means of rulings. With this practice,

Still Your Heart!’, traditionally known as ‘Marduk 1’.26 This common also in manuscripts of other “great hymns”,

text was one of the most popular works of Babylonian liter- scribes originally intended to scan the poetic couplets of

ature in ancient Mesopotamia: it was transmitted in a vir- the text. However, “late scribes insert the vertical spacing

tually unaltered form from approximately the seventeenth with supreme disregard as to what should go on each

century BCE to the year 35 BCE, and thus represents one the side of it, so in the late copies these rulings are put quite

most long-lived religious texts in world’s history. One of the mechanically even when a single line or group of three

manuscripts of the text (BM 34218+(+)),27 is in fact the latest has thrown them out of place” (Lambert 2013, 28). This is

datable non-astronomical tablet yet known. also the case of the ruled manuscripts of ‘Marduk 1’, such

The text belongs to the loosely defined category of as the present one: extraneous lines, such as l. 60, cause

“great hymns”, along with the ‘Šamaš Hymn’ (Lambert the rulings no longer to divide poetic couplets, but simply

1960a, 121–138), the ‘Marduk Hymn 2’ (Lambert 1960b, pairs of lines of text.

⁂

pened to him.” On the historicity of Šubši-mešrê-Šakkan, see Lam-

bert (1995, 33 f.) and Oshima (2014, 16 f.). The text is currently known from twelve discrete manu-

23 Compare e. g. the imitation of ‘Ludlul’ I 41–42 in the prayer scripts comprising forty different fragments, and eight

K.9252+ and dupl. ll. 7 f. (Jiménez 2014, 111), and the parody of ‘Lud- extracts on school tablets. Three of the manuscripts

lul’ I 44 in the ‘Series of the Fox’ § Z rev 4′ (Jiménez 2017a, 83). Lines

belong to the British Museum’s “Sippar Collection,” and

from ‘Ludlul’ are adduced by many ancient exegetes in their com-

mentaries (Frahm 2011, 102 f.), and may be cited in Neo-Assyrian

may thus stem from the city of Sippar. This is probably the

correspondence (for some uncertain cases, see Lambert 1995, 34 and case of the only known Old Babylonian manuscript of the

Hurowitz 2008, 81–82). text, BM 78278 (CT 44, 21 = CTL 1, 81), which belongs to

24 K.9952 (Lambert 1960a, pl. 12), BM 38611 (Oshima 2014, pl. 31) (+) the consignment Bu.88-5-12, the majority of whose tablets

BM 38339 (unpubl., kindly brought to our attention as a literary frag- date to around the time of Hammurapi and come most

ment by J. C. Fincke and C. B. F. Walker). The text is edited by Oshima

likely from Sippar (Leichty [e. a.] 1988, 17). The poem,

(2014, 465–469) and Frazer (2015, 18–36).

25 A fragment, previously included in the collection of fragments therefore, was transmitted in the city of Sippar for well

under the number IM 124566 (Sippar 8, 099/2262), was joined to IM over a millennium.

124504. A new edition of the text by E. Jiménez, based on the

26 Published by Lambert (1960b, 55–60) and Oshima (2011, 137–190). use of many unpublished manuscripts, is in an advanced

27 Copies of some of the fragments that constitute this tablet have

state of preparation, so the philological discussion is here

appeared as Oshima 2011, pl. iii and CTL 1, 88 (BM 34218+ BM 34334),

CTL 1, 85 (BM 34366), and Oshima 2011, pls. vi-vii and CTL 1, 85 (BM

kept to a minimum. A circellus (°) marks signs visible in

45746). Three additional pieces of the manuscript have been identified old photographs of IM 124504, but currently missing from

by Jiménez and will be published in his forthcoming edition of the text. the tablet.

� Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I 163

Fig. 4: IM 124504 shortly after the excavation, before conservation

�164 Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I

Fig. 5: IM 124504 after conservation (March 2018)

� Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I 165

70

65

60

75

55

col. ii

1 cm

col. i

20

15

5

10

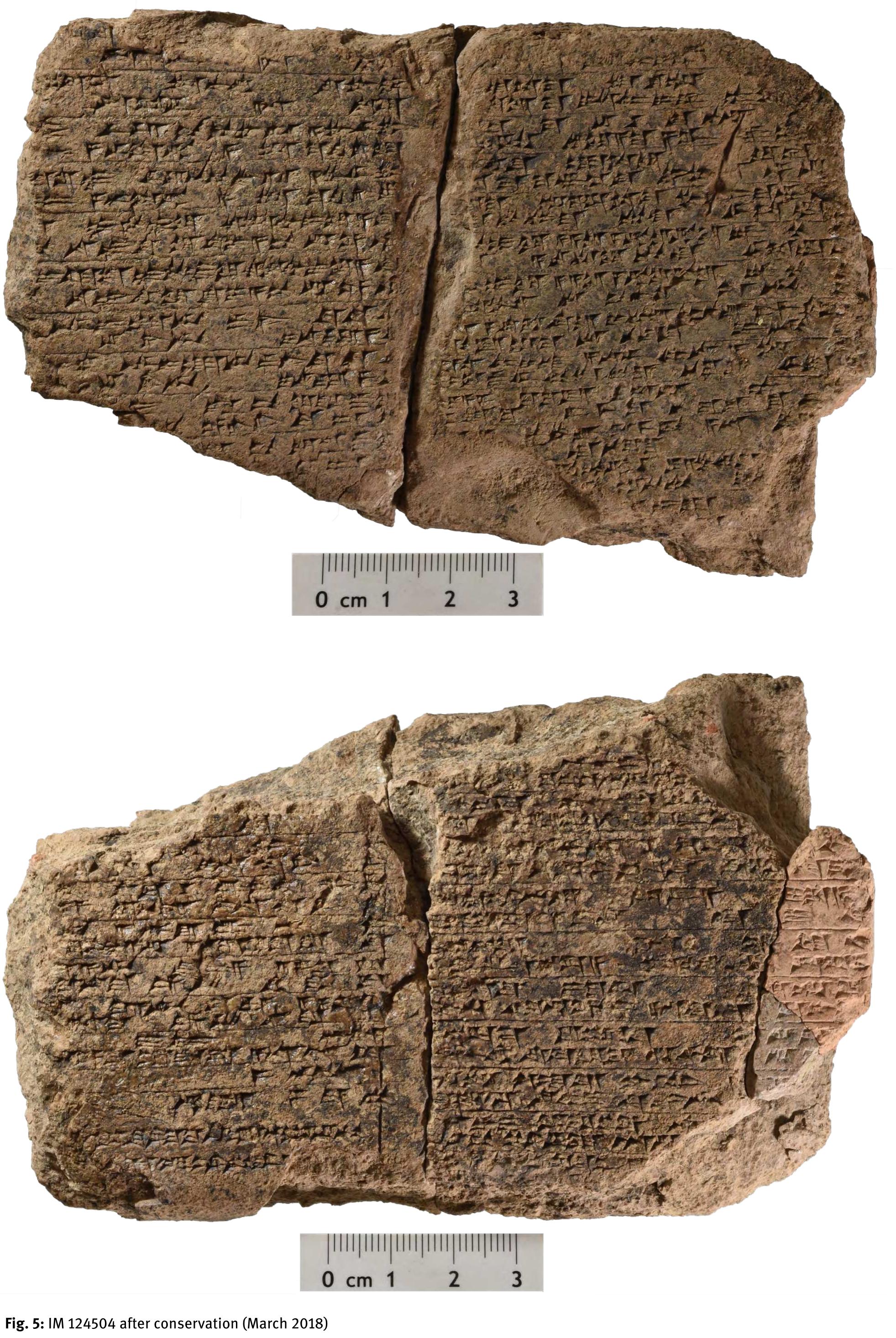

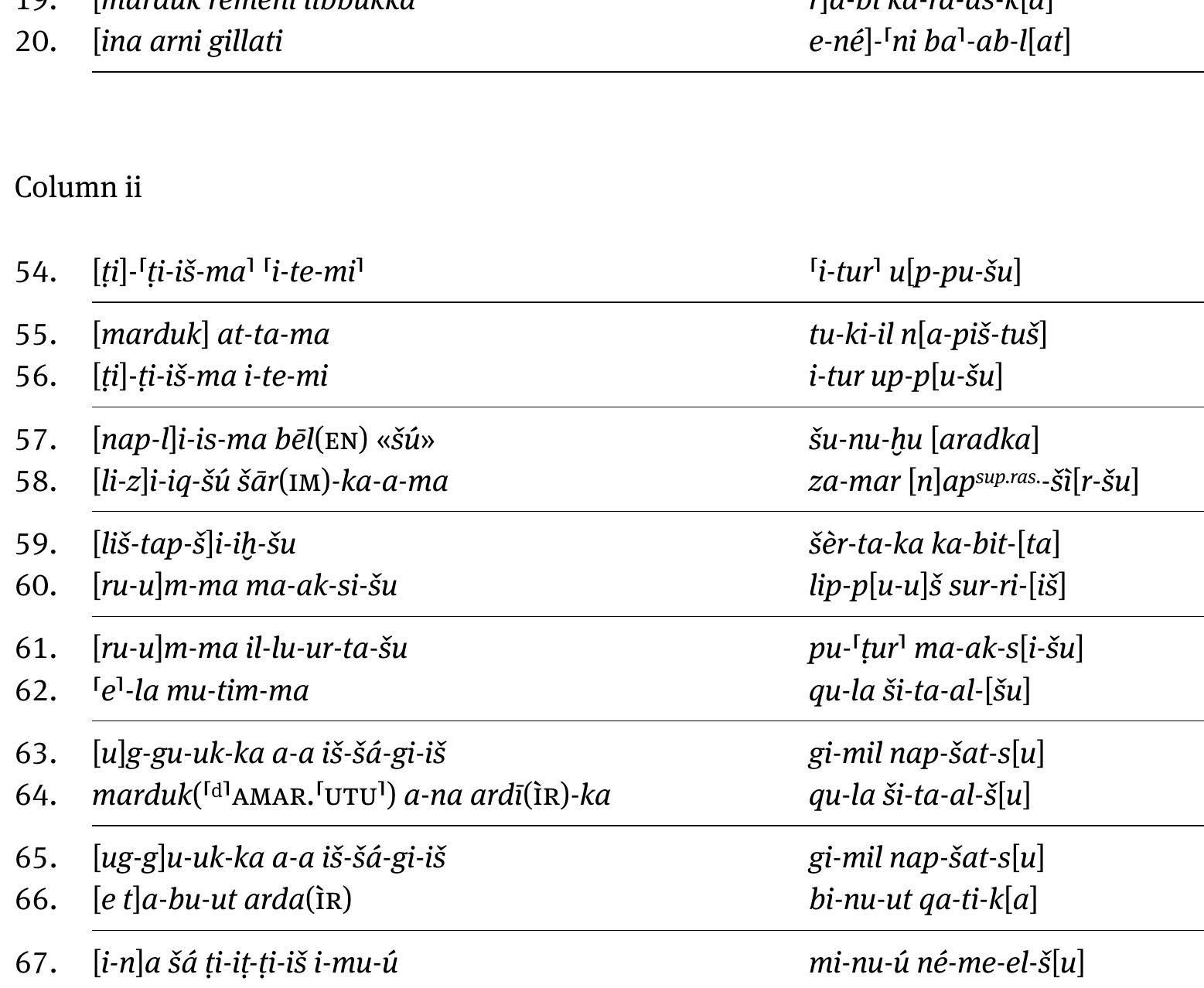

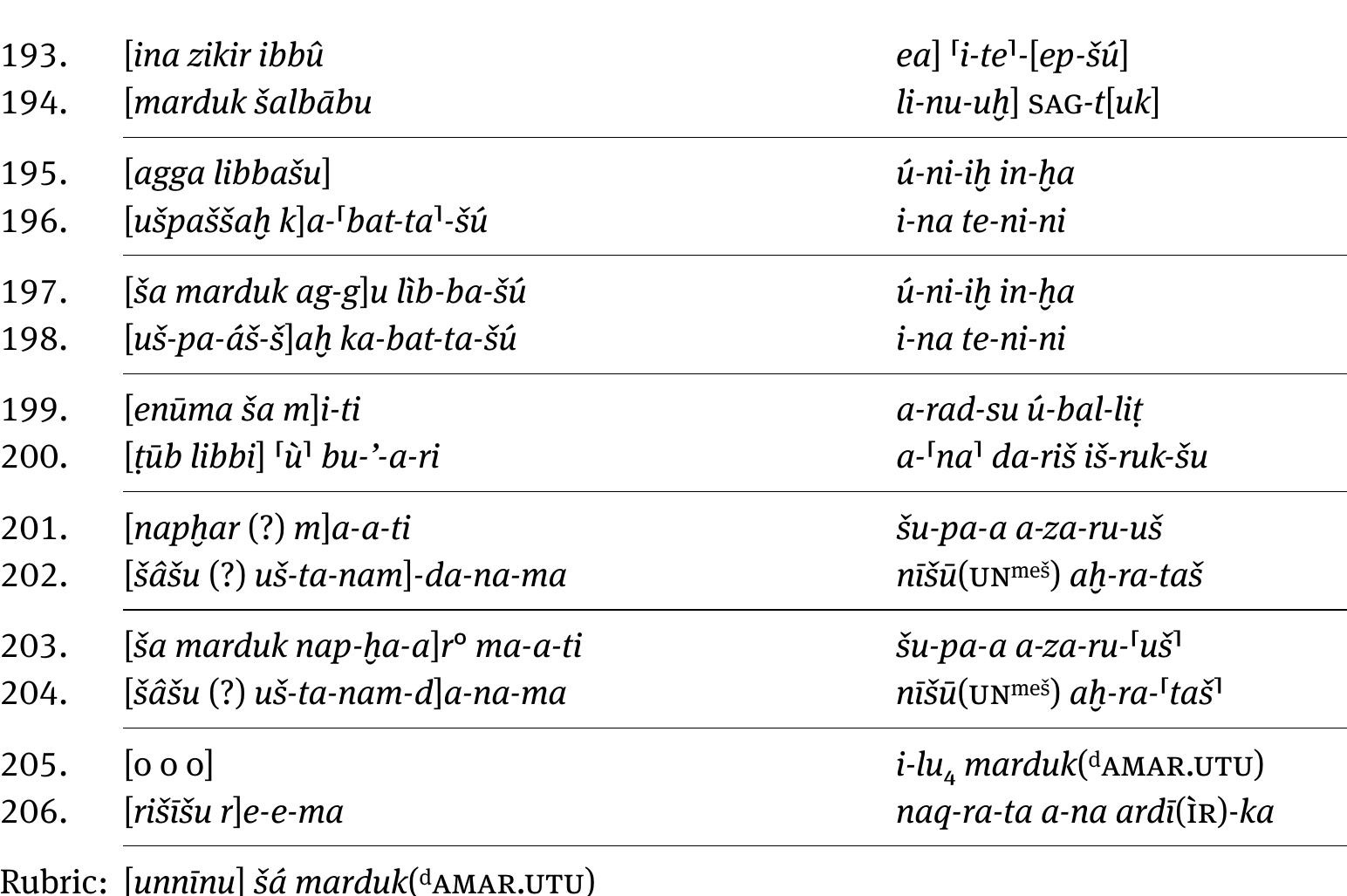

Fig. 6: IM 124504 obverse, Copy by Anmar A. Fadhil

�166 Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I

146

141

151

156

col. iii

1 cm

col. iv

207

197

202

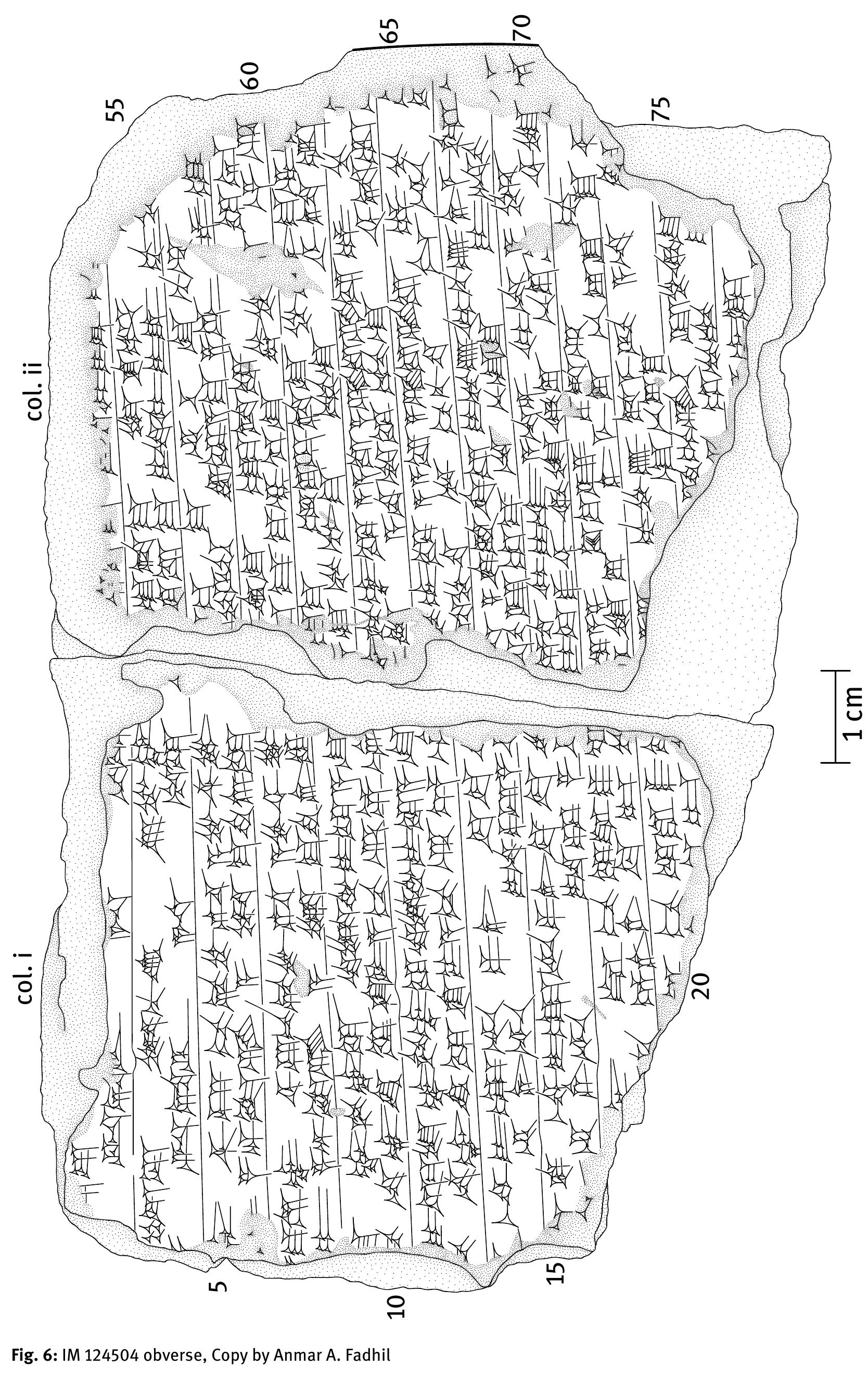

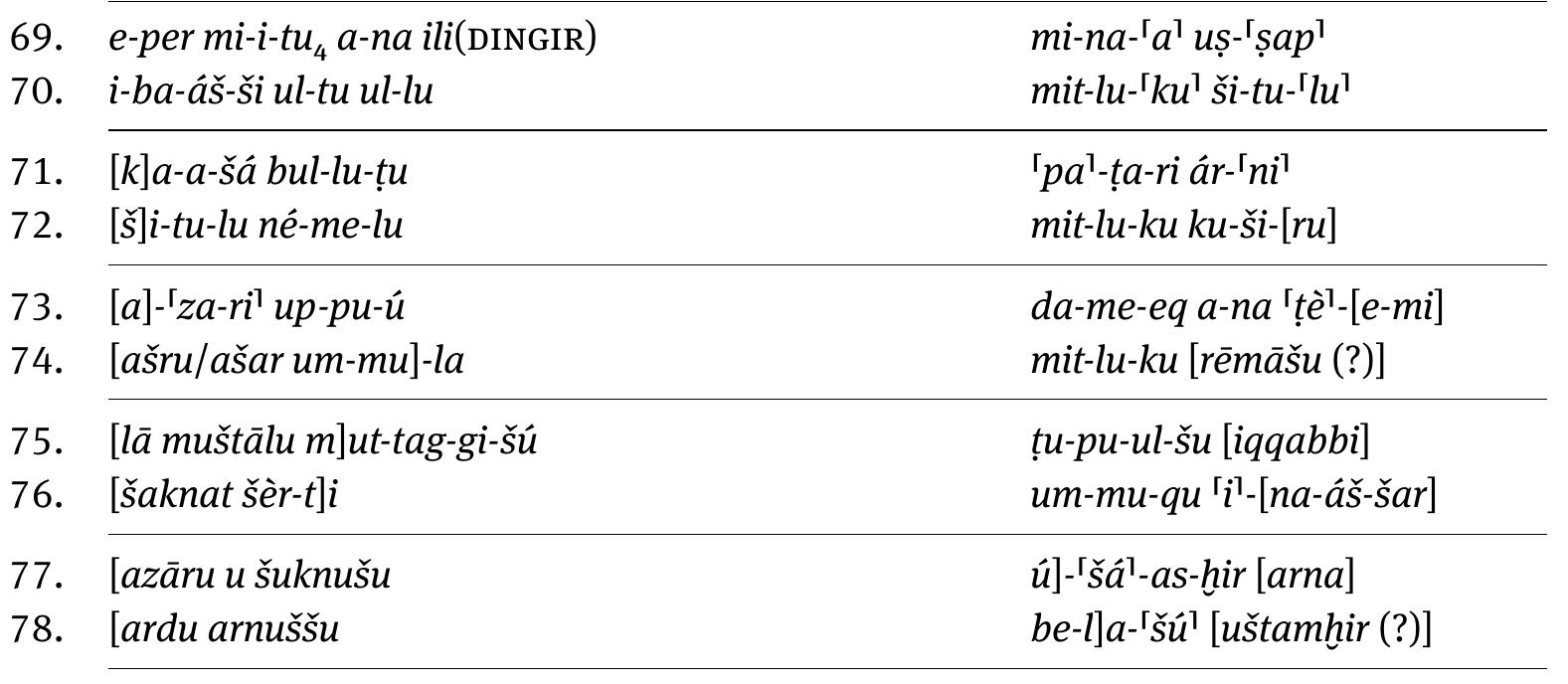

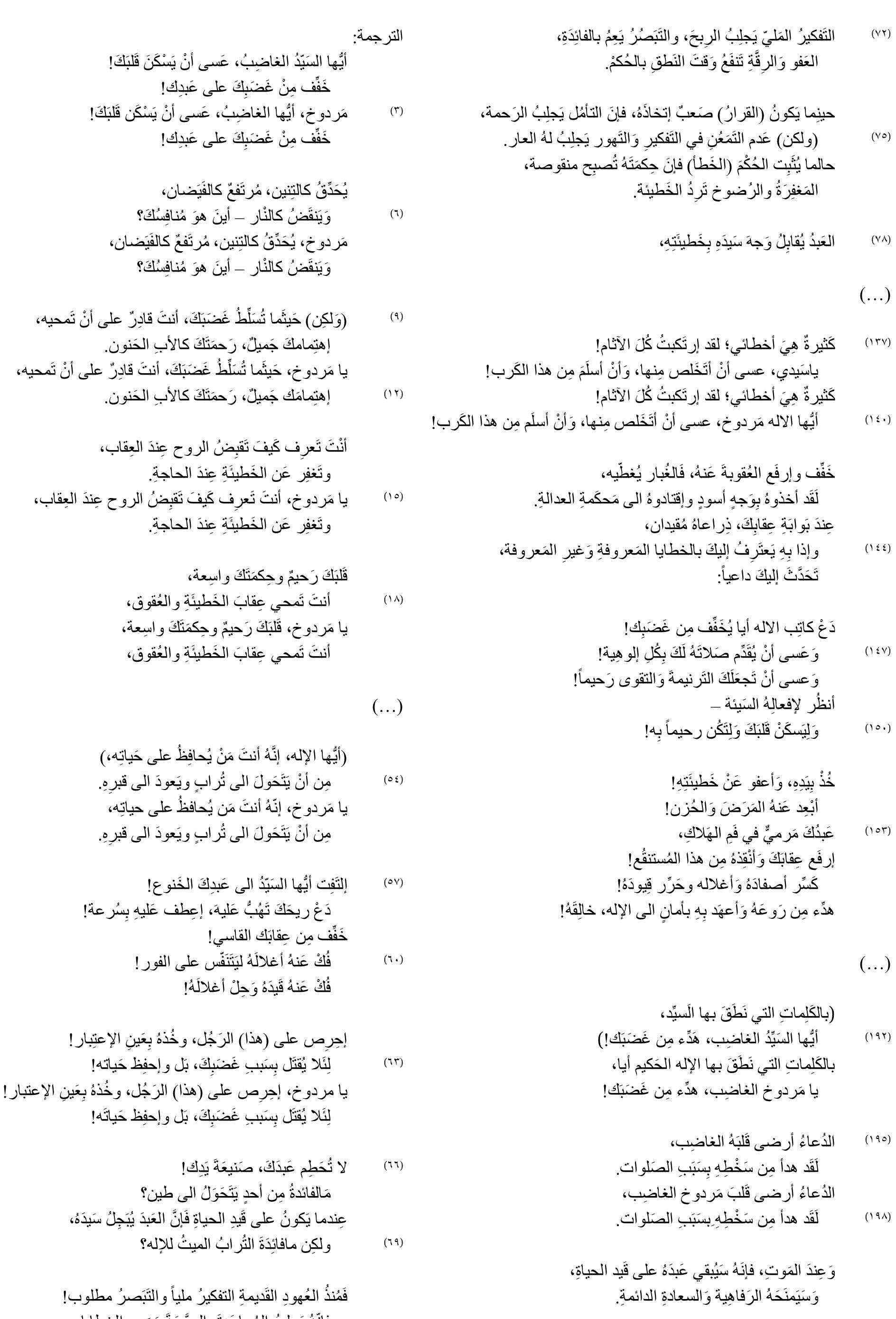

Fig. 7: IM 124504 reverse, Copy by Anmar A. Fadhil

� Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I 167

Column i

1. [bēlu še-z]u-zu [linūḫ libbuk]

2. [i tapšaḫ] kab-⸢ta-tuk⸣ a-na ⸢ardī(ìr)-ka⸣

3. [marduk] še-zu-zu li-nu-uḫ lìb-bu-uk

4. [i tap-ša]ḫ kab-ta-tuk a-na ardī(ìr)-ka

5. [šá a-ma-ru-u]k ši-ib-bi ga-pu-uš a-bu-ši-in

6. [šá-áš-m]i šá dgíra a-li ma-ḫi-ir-ka

7. [marduk ša] ⸢a⸣-ma-ru-uk ši-ib-bi ga-pu-uš a-bu-ši-in

8. [šá-áš-m]i šá dgíra a-li ma-ḫi-ir-ka

9. [ki?-i sak-t]u ug-gu-uk-ka te-le-ʼ-i ka-a-šu

10. [ṭa-b]i na-as-ḫur-ka ki-i a-bi re-e-muk

11. [marduk ki?]-i sak-tu ug-gu-uk-ka te-le-ʼ-i ka-a-šu

12. [ṭa-b]i na-as-ḫur-ka ki-i a-bi re-e-mu[k]

13. [te-d]i ina pi-i šèr-ti pa-ni ba-ba-l[i]

14. [pa-ṭa-r]a en-né-ti i-na šap-šá-q[í]

15. [marduk t]e-di ina pi-i šèr-ti pa-ni ba-ba-l[i]

16. [pa-ṭa-r]a en-né-ti i-na šap-šá-q[í]

17. [rēmēni lib-bu-u]k ra-bi ka-ra-áš-⸢ka⸣

18. [ina arni gíl-la-t]i e-né-ni ba-ab-lat

19. [marduk rēmēni libbukka r]a-bi ka-ra-áš-k[a]

20. [ina arni gillati e-né]-⸢ni ba⸣-ab-l[at]

Column ii

54. [ṭi]-⸢ṭi-iš-ma⸣ ⸢i-te-mi⸣ ⸢i-tur⸣ u[p-pu-šu]

55. [marduk] at-ta-ma tu-ki-il n[a-piš-tuš]

56. [ṭi]-ṭi-iš-ma i-te-mi i-tur up-p[u-šu]

57. [nap-l]i-is-ma bēl(en) «šú» šu-nu-ḫu [aradka]

58. [li-z]i-iq-šú šār(im)-ka-a-ma za-mar [n]apsup.ras.-šì[r-šu]

59. [liš-tap-š]i-iḫ-šu šèr-ta-ka ka-bit-[ta]

60. [ru-u]m-ma ma-ak-si-šu lip-p[u-u]š sur-ri-[iš]

61. [ru-u]m-ma il-lu-ur-ta-šu pu-⸢ṭur⸣ ma-ak-s[i-šu]

62. ⸢e⸣-la mu-tim-ma qu-la ši-ta-al-[šu]

63. [u]g-gu-uk-ka a-a iš-šá-gi-iš gi-mil nap-šat-s[u]

64. marduk(⸢d⸣amar.⸢utu⸣) a-na ardī(ìr)-ka qu-la ši-ta-al-š[u]

65. [ug-g]u-uk-ka a-a iš-šá-gi-iš gi-mil nap-šat-s[u]

66. [e t]a-bu-ut arda(ìr) bi-nu-ut qa-ti-k[a]

67. [i-n]a šá ṭi-iṭ-ṭi-iš i-mu-ú mi-nu-ú né-me-el-š[u]

68. [b]al-ṭu-um-ma ardu(ìr) be-la-šu i-pal-[làḫ]

�168 Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I

69. e-per mi-i-tu₄ a-na ili(dingir) mi-na-⸢a⸣ uṣ-⸢ṣap⸣

70. i-ba-áš-ši ul-tu ul-lu mit-lu-⸢ku⸣ ši-tu-⸢lu⸣

71. [k]a-a-šá bul-lu-ṭu ⸢pa⸣-ṭa-ri ár-⸢ni⸣

72. [š]i-tu-lu né-me-lu mit-lu-ku ku-ši-[ru]

73. [a]-⸢za-ri⸣ up-pu-ú da-me-eq a-na ⸢ṭè⸣-[e-mi]

74. [ašru/ašar um-mu]-la mit-lu-ku [rēmāšu (?)]

75. [lā muštālu m]ut-tag-gi-šú ṭu-pu-ul-šu [iqqabbi]

76. [šaknat šèr-t]i um-mu-qu ⸢i⸣-[na-áš-šar]

77. [azāru u šuknušu ú]-⸢šá⸣-as-ḫir [arna]

78. [ardu arnuššu be-l]a-⸢šú⸣ [uštamḫir (?)]

Column iii

137. [ma]-⸢ʼ°-du°-ma°⸣ an-nu-ú-a a[ḫ-ta-ṭi kalāma]

138. [b]e-⸢lu₄⸣ ⸢an-ni-ta⸣ lu-ú e-ti-iq lu-⸢ú⸣-[ṣi ina šapšāqi]

139. [m]a-ʼ-du-ma an-nu-ú-a aḫ-t[a-ṭi kalāma]

140. marduk([dama]r.utu) an°-ni-⸢ta⸣ lu-ú e-⸢ti-iq⸣ lu-ú-ṣ[i ina šapšāqi]

141. [ḫ]u-⸢um⸣-mu-um na-ši ⸢šèr-ta⸣ e-pe-ri k[a]-ši-[šú]

142. [i]l-qu-šu ⸢e-kil⸣ pa-ni ur-ru-šu áš-ri-⸢iš⸣ di-i-⸢ni⸣

143. ⸢i⸣-na bāb(ká) še-er-ti-ka ka-sa-a i-da-a-š[u]

144. ⸢ú⸣-pa-áš-šar-kúm-ma i-di la i-⸢di⸣

145. ⸢i⸣-ta-mu-ka i-na ⸢un⸣-nin-nu

146. ši-iṭ-ru šá dé-a li-šap-⸢šiḫ⸣ kab-ta-tuk

147. [t]e-mi-qí-šu i-lu-uš lu-ki-il-ka

148. [i]n-ḫu ù re-e-mi a-ḫu-la-ap liq-bu-k[a]

149. ⸢a⸣-mu-ur-ma ep-še-ta-šu ⸢ma⸣-ru-uš-[ta]

150. [l]i-nu-uḫ lìb-ba-ka-ma ri-ši-iš re-⸢e⸣-[ma]

151. ⸢a⸣-ḫu-uz qa-at-su pu-ṭur ⸢a-ra⸣-[an-šú]

152. [š]u-us-si di-ʼ-i di-lip-ti [e-li-šu]

153. ⸢i⸣-na pi-i ka-ra-še-e na-[di aradka]

154. [š]u-ut-bi še-er-tuk-ka ina na-ri-[ṭi eṭraššu]

155. [ḫ]e-⸢pi⸣ ⸢qu-un-nab⸣-ra-šu il-⸢lu⸣-[ur-ta-šú puṭur maksīšu]

156. [nummiršū-m]a [šalmiš piqissu iliš bānīšu]

(end of column)

� Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I 169

Column iv

193. [ina zikir ibbû ea] ⸢i-te⸣-[ep-šú]

194. [marduk šalbābu li-nu-uḫ] sag-t[uk]

195. [agga libbašu] ú-ni-iḫ in-ḫa

196. [ušpaššaḫ k]a-⸢bat-ta⸣-šú i-na te-ni-ni

197. [ša marduk ag-g]u lìb-ba-šú ú-ni-iḫ in-ḫa

198. [uš-pa-áš-š]aḫ ka-bat-ta-šú i-na te-ni-ni

199. [enūma ša m]i-ti a-rad-su ú-bal-liṭ

200. [ṭūb libbi] ⸢ù⸣ bu-ʼ-a-ri a-⸢na⸣ da-riš iš-ruk-šu

201. [napḫar (?) m]a-a-ti šu-pa-a a-za-ru-uš

202. [šâšu (?) uš-ta-nam]-da-na-ma nīšū(unmeš) aḫ-ra-taš

203. [ša marduk nap-ḫa-a]r° ma-a-ti šu-pa-a a-za-ru-⸢uš⸣

204. [šâšu (?) uš-ta-nam-d]a-na-ma nīšū(unmeš) aḫ-ra-⸢taš⸣

205. [o o o] i-lu₄ marduk(damar.utu)

206. [rišīšu r]e-e-ma naq-ra-ta a-na ardī(ìr)-ka

Rubric: [unnīnu] šá marduk(damar.utu)

Catchline: [mušnammir] gi-mir šá-ma-mu

Colophon: [kī labīrī-š]u ša-ṭi-ir-ma ba-ri ṭuppi(dub) mmarduk(damar.utu)-bēl(en)-zēri(numun)

[o o o] x ⸢qāt(šumin)⸣ mnabû(d+ag)-tab-ni-uṣur(urì) mār(dumu) ⸢m⸣[o o o]

(end of column)

Translation

[Fur]ious [lord, still your heart]!

[Calm] your choler against your servant!

(3) Furious [Marduk], still your heart!

[Cal]m your choler against your servant!

[Whose star]e is a dragon, a flood overwhelming,

(6) [An onslaught o]f fire — where is your rival?

[Marduk, whose st]are is a dragon, a flood overwhelming,

[An onslaug]ht of fire — where is your rival?

(9) [(But) when] your wrath [has qui]eted, you are able to rescue,

Your attention is [swee]t, like a father’s your mercy.

O Marduk! [Wh]en your wrath has quieted, you are able to rescue,

(12) Your attention is [swee]t, like a father’s your mercy.

[You kno]w how, in punishment, to extend forgiveness,

[To absol]ve sin when in sorrow.

(15) [O Marduk! Y]ou know how, in punishment, to extend forgiveness,

[To absolv]e sin when in sorrow.

[Merciful is your hear]t, your mind is generous,

�170 Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I

(18) You take away the punishment [for fault (and) impie]ty.28

[O Marduk! Merciful is your heart], your mind is gen[e]rous,

You take away [the punis]hment [for fault (and) impiety].

(…)

(O Lord! It is you who preserves his life,)

(54) (Of) him turned to [cl]ay, returned to [his] gr[ave],

[O Marduk!] It is you who preserves [his] l[ife],

(Of) him turned to [c]lay, returned to [his] grav[e].

(57) [Rega]rd, O Lord, your wearied [servant!]

[Let] your breath blow upon him, [r]ele[nt] in an instant!

[Soot]he your hea[vy] punishment!

(60) [Loo]sen his shackles, that he bre[at]he forth[with]!

[Loo]sen his fetters, release [his] shack[les]!

Heed the man, consider [him]!

(63) Lest in your [ra]ge he be slaughtered, spare hi[s] life!

O Marduk! Heed your servant, consider h[im]!

Lest in your [r]age he be slaughtered, spare hi[s] life!

(66) [Do not d]estroy your servant, the work of yo[ur] hands,

What profi[t is there i]n one turned to clay?

[When a]live, the servant reve[res] his lord,

(69) But the dead dust, what us[e] is it to the god?

It is since yesteryear meet to meditate and reflect,

(it brings) [he]lp, health, and absolution of sins.

(72) [To r]eflect (brings) profit; to meditate, benef[it],

[To for]give29 and to spare are valuable for the judgement.

[Where (judgment) is clo]udy, meditation [(brings) mercy],

(75) [(But) the irreflective, the r]eckless, his infamy [spreads].

[Once] punishment is [impos]ed, circumspection l[essens (it)],

[Forgiveness and acquiescence re]pulse [sin].

(78) [The servant confronts] his [lor]d [with his sin],

(…)

(137) “[Ma]ny are my faults; I h[ave committed every sin]!

“[O L]ord, may I overcome this and esc[ape when in sorrow]!

“[Ma]ny are my faults; I have comm[itted every sin]!

(140) “[O Mar]duk, may I overcome this and esca[pe when in sorrow]!”

28 The rest of the manuscript tradition reads: “you take away the transgression in fault (and) impiety.”

29 The Old Babylonian MS BM 78278 (CT 44, 21; CTL 1, 81) reads “to be attentive.”

� Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I 171

[Cu]rtailed, bearing the punishment, dust [co]vering him,

[They to]ok him, dark his face, bearing him to the court of justice.

At the gate of your punishment, h[is] arms are bound

(144) [(As) he c]onfesses to you (sins) known and unknow[n],

[Sp]eaking to you in supplication:

Let the writing of Ea cal[m] your choler!30

(147) Let him offer his [or]ison to you as his god.

Let (his) chant and piety move you to compas[sion].

[Be]hold his misled ac[ts] —

(150) [St]ill your heart and have mer[cy] on him!

[T]ake his hand, absolve [his] si[n]!

[P]ut [his] fever and distress to flight!

(153) Your [servant] li[es] in the jaws of destruction,

[Li]ft your punishment, [rescue him] from the mi[re]!

[Bre]ak his shackles and fe[tters, release his bonds]!

(156) [Comfort him, a]nd [safely entrust him to the god his creator]!

(…)

(By the words the lord has uttered,

(192) Furious Lord, calm your choler!)

[By the words] wi[se Ea has uttered],

[Furious Marduk, calm] yo[ur] choler!

(195) The supplication has placated [his furious heart],

[He has calmed] his [ch]oler thanks to the prayer.

[Of Marduk], the supplication has placated his [furio]us heart,

(198) [He has ca]lmed his choler thanks to the prayer.

[Whereupon him who was de]ad, his servant, he cured,

[Welfare a]nd happiness he granted him permanently.

(201) His forgiveness is manifest [to the entire l]and,

The peoples henceforth shall [pon]der [him!]

[Of Marduk,] hi[s] forgiveness is manifest [to the enti]re land,

(204) The peoples henceforth shall [pond]er [him!]

(205) […] the god, Marduk!

[Have] mercy [on him], clemency towards your servant!

Rubric: “[Supplication] to Marduk”

Catchline: “[Luminary] of all heavens” (= ‘Šamaš Hymn’)

Colophon: Written [according to it]s [original] and collated.

Tablet of Marduk-bēl-zēri, […] … Hand(writing) of Nabû-bani-uṣur, son of … […]

⁂

30 Other manuscripts read: “… calm your heart!”

� 172 Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I

الترجمة: الرب َح ،والتَبَ ُ

ص ُر يَ ِع ُم بالفائِ َد ِة، التَفكي ُر ال َمل ّي يَجلِبُ ِ

)(٧٢

أن يَ ْس َكنَ قَلبَكَ!

الغاضبُ ،عَسى ْ

ِ أيُّها ال َسيّ ُد َطق بالحُك ْم.ِ ن ال قتَ الرقَّ ِة تَنفَ ُع َو

ال َعفو َو ِ

ك على عَب ِدك! َخفِّف ِم ْن َغ َ

ضب ِ َ

أن يَ ْسكَن قَلبَكَ!الغاضبُ ،عَسى ْ

ِ َمردوخ ،أيُّها )(٣

صعبٌ إتخا َذهُ ،فإنَ التأ ُمل يَجلِبُ ال َرحمة، حينِما يَكونُ (القرارُ) َ

ك على عَب ِدك!ضبِ ََخفِّف ِم ْن َغ َ َفكير َوالتَهور يَجلِبُ لهُ العار.(ولكن) عَدم التَ َمع ُِن في الت ِ

)(٧٥

حالما يُثَبِت ال ُح ْك َم (الخَطأ) فإنَ ِحك َمتَهُ تُصبِح منقوصة،

ق كالتِنينُ ،مرتَف ٌع كالفَيَضان، يُ َح ِّد ُ ال َمغفِ َرةُ والرُضوخ ت َِر ُد الخَطيئة.

ْ

َويَنقضُ كالنار – أينَ ه َو ُمنافِ ُسكَ؟ َ )(٦

ق كالتِنينُ ،مرتَف ٌع كالفَيَضان، َمردوخ ،يُ َح ِّد ُ ال َعب ُد يُقابِ ُل َوجهَ َسي َد ِه بِخَطيئَتِ ِه، )(٧٨

َويَنقَضُ كال ْنار – أينَ ه َو ُمنافِ ُسكَ؟

(…)

ضبَكَ ،أنتَ قا ِد ٌر على ْ

أن تَمحيه، ( َول ِكن) َحيثَما تُ َسلِّطُ َغ َ )(٩

ب ال َحنون. ك كاأل ِ ك َجميلٌَ ،رح َمتَ َ إهتِمام َ َكبت ُك َل اﻵثام!

كَثيرةٌ ِه َي أخطائي؛ لقد إرت ُ )(١٣٧

أن تَمحيه، يا َمردوخَ ،حيثَما تُ َسلِّطُ َغ َ

ضبَكَ ،أنتَ قا ِد ٌر على ْ أن أسلَ َم ِمن هذا الكَرب!

أن أتَخَلص ِمنهاَ ،و ْ

يا َسيدي ،عسى ْ

ب ال َحنون. ك كاأل ِ إهتِما َمك َجميلٌَ ،رح َمتَ َ )(١٢

َكبت ُك َل اﻵثام!

كَثيرةٌ ِه َي أخطائي؛ لقد إرت ُ

أن أسلَم ِمن هذا الكَرب!

أن أتَخَلص ِمنهاَ ،و ْ أيُّها االله َمردوخ ،عسى ْ )(١٤٠

َعرف َكيفَ تَقبِضُ الروح ِعن َد ال ِعقاب، أ ْنتَ ت ِ

وتَغفِر عَن الخَطيئَ ِة ِعن َد الحاج ِة. َخفِّف وإرفَع العُقوبةَ عَنهُ ،فَال ُغبار يُغطّيه،

َعرف َكيفَ تَقبِضُ الروح ِعن َد ال ِعقاب، يا َمردوخ ،أنتَ ت ِ

)(١٥

لَقَد أخذوهُ بِ َوج ٍه أسو ٍد وإقتادوهُ الى َمحكَم ِة العدال ِة.

َ

وتَغفِر عَن الخَطيئ ِة ِعن َد الحاج ِة. ِعن َد بَوابَ ِة ِعقابِكَِ ،ذراعاهُ ُمقيدان،

غير ال َمعروفة،

ك بالخطايا ال َمعروف ِة َو ِ وإذا بِ ِه يَعت َِرفُ إلي َ )(١٤٤

واسعة،

ك ِ وحك َمتَ َ

ك َرحي ٌم ِقَلبَ َ ك داعياً: ث إلي َ تَ َح َّد َ

قاب الخَطيئَ ِة والعُقوق،

أنتَ تَمحي ِع َ )(١٨

واسعة،

ك ِ وحك َمتَ َ

ك َرحي ٌم ِ يا َمردوخ ،قَلبَ َ ضبِك! َد ْع كاتِب االله أيا يُ َخفِّف ِمن َغ َ

قاب الخَطيئَ ِة والعُقوق،

أنتَ تَمحي ِع َ ك بِ ُك ِل إلو ِهية!

صالتَهُ لَ َ

أن يُقَدِّم َ َوعَسى ْ )(١٤٧

ك التَرنيمةَ َوالتقوى َرحيماً! أن تَج َعلَ َ َوعسى ْ

(…) أنظُر إلفعالِهُ ال َسيئة –

ك َولِتَ ُكن رحيما ً بِه! َولِيَسك َْن قَلبَ َ )(١٥٠

(أيُّها اإلله ،إنَّهُ أنتَ َم ْن يُحافِظُ على َحياتِه)،

قبر ِه.

ب ويَعو َد الى ِأن يَتَ َحو َل الى تُرا ٍ

ِمن ْ )(٥٤

ُخ ْذ بِيَ ِد ِهَ ،وأعفو ع َْن خَطيئَتِ ِه!

يا َمردوخ ،إنّهُ أنتَ َمن يُحافظُ على حياتِه، ض َوالحُزن! أ ْب ِعد عَنهُ ال َم َر َ

قبر ِه.

ب ويَعو َد الى ِأن يَتَ َحو َل الى تُرا ٍ

ِمن ْ ك َمرم ٌّي في فَ ِم الهَ ِ

الك، عَب ُد َ )(١٥٣

ُ

ك َوأنقِذهُ ِمن هذا ال ُمستنقع! ْ إرفَع ِعقابَ َ

ك الخَنوع! إلتَفِت أيُّها ال َسيّ ُد الى عَب ِد َ )(٥٧

َكسِّر أصفا َدهُ َوأغالله و َحرِّر قِيو َدهُ!

ك تَهُبُّ عَليهَ ،إ ِعطف عَلي ِه بِسُرعة! َد ْع ري َح َ بأمان الى اإلله ،خالِقَهُ!

ٍ هدِّء ِمن َرو َعهُ َوأعهَد بِ ِه

َخفِّف ِمن ِعقابَك القاسي!

فُ ْك عَنهُ أغاللَهُ ليَتَنَفّس على الفور! )(٦٠

(…)

فُ ْك عَنهُ قَي َدهُ َو ِحلْ أغاللَهُ!

ت التي نَطَ َ

ق بها الَسيِّد، )بال َكلِما ِ

ين اإلعتِبار! إح ِرص على (هذا) ال َرجُل ،و ُخذهُ بِ َع ِ ِ ضبَك!( َ

الغاضب ،هَدِّء ِمن غ َ ِ ُ

أيُّها ال َسيِّد )(١٩٢

ضبِكَ ،بَل وإحفِظ َحياته! ب َغ َ لِئَال يُقتَل بِ َسب ِ )(٦٣

ق بها اإلله ال َحكيم أيا، ت التي نَطَ َ بال َكلِما ِ

إح ِرص على (هذا) ال َرجُل ،و ُخذهُ بِ َع ِ

ين اإلعتبار! يا مردوخِ ، الغاضب ،هدِّء ِمن َغ َ

ضبَك! ِ يا َمردوخ

ضبِكَ ،بَل وإحفِظ َحياتَه! ب َغ َ لِئَال يُقتَل بِ َسب ِ

الغاضب،

ِ الدُعا ُء أرضى قَلبَهُ )(١٩٥

صني َعةَ يَ ِدك!ال تُ َح ِطم عَب َدكََ ، )(٦٦

صلوات.ب ال َلَقَد هدأ ِمن َس ْخ ِط ِه بِ َسبَ ِ

َمالفائدةُ ِمن أح ٍد يَتَ َح َو ُل الى طين؟ الغاضب،

ِ لب َمردوخ الدُعا ُء أرضى قَ َ

ِعندما يَكونُ على قَي ِد الحيا ِة فَ َّ

إن ال َعب َد يُبَ ِج ُل َسي َدهُ، صلوات. ب ال َلَقَد هدأ ِمن َس ْخ ِط ِه ِب َسبَ ِ )(١٩٨

ُ

الميت لإلله؟ ول ِكن مافائِ َدةَ التُرابُ )(٦٩

ت ،فإنَهُ َسيُبقي عَب َدهُ على قَيد الحيا ِة، َو ِعن َد ال َمو ِ

فَ ُمن ُذ العُهو ِد القَديم ِة التفكي ُر مليا ً والتَبَص ُر مطلوب! َو َسيَمنَ َحهُ ال َرفا ِهية َوالسعاد ِة الدائم ِة.

فإنّهُ يَجلِبُ ال ُمساعَدةَ ،ال َّ

ص َحةَ َو َمحو الخطايا.

� Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I 173

،األرض ِ ِواض َحةٌ لِ ُك ِل َمن في ب

قاع ِ َُمغفِ َرتَه uscript with many other mistakes,32 should be emended

(٢٠١)

ِ

!الناس ِمن االن فَصاعداً التأ ُم ُل َملِّيا ً فيما بَينَهُم به ِ على َو to ki!. Accordingly, one expects the Sippar manuscript to

،األرض

ِ قاع

ِ ِ ب في ن م

َ ِل ُ

ك ِ ل واضحة ُ هَ ترَ ِ ف غمَ ،ردوخ م

َ االله contain the writing [ki]-i. Compare ‘Marduk 2’ 68: kī ītennu

!الناس ِمن االن فَصاعداً التأ ُم ُل َملِّيا ً فيما بَينَهُم بِه ِ َوعلى (٢٠٤)

bēlu ištaʼal irēm ušpaššiḫ, “once the lord has raged, he

reflects, has mercy, and relents.” The verb sakātu, “to be

![…] اإلله َمردوخ (٢٠٥)

silent,” is not attested in the sense of “to quiet down,” but

! وإرأف بِ َعب ِدك،ُإر َحمه the concept seems acceptable in the context.

17//19. ra-bi is written ra-bi (with “overhanging vowel”)

” “تَرنيمةُ الى اإلله َمردوخ:العُنوان in the present MS and in the Neo-Babylonian MS BM 76492

ت” (= ترنيمةُ اإلل ِه ِ “يا ُمني َر السماوا:لسلة

ِ الس

ِ ال َسطر األول للنَص الذي يتبَعهُ في (Oshima 2011, pl. i; CTL 1, 84), but [r]a-a-bi in the Late

)َش َمش Babylonian MS BM 45746 (Oshima 2011, pls. vi-vii; CTL 1,

َ َ ُ َ َ

– لوح َمردوخ. ت َّمت ِكتابَتهُ وتَدقيقهُ (للوح) كما هُو بالنسخ ِة األصلية:التَذييل 85) and [ra]-⸢i⸣-ib in the OB MS BM 78278 (CT 44, 21; CTL

]…[ … إبن، […] … ِكتابةُ يَد نابو – باني – أوصور،بيل – زيري 1, 81). The word should be parsed as riābu, “to restore”:

compare the writing ra-ʼ-bu || ra-a-bi || [ra]-ʼ-bi {bi} of

raʼbu, “(where) he was angry” (‘Erra’ V 12, see Cagni 1969,

Philological Commentary 122–123). Compare marduk rāʼib ašar ībut[u o (o)], “Marduk

restores where he destroy[ed …]” (‘Marduk 2’ 76).

5//7. The understanding of the line, the second part of which 18//20. The manuscript tradition reads here unan-

appears verbatim in ‘Marduk 2’ 80//82, remains problem- imously e-te-qa instead of e-né-ni (the OB MS BM 78278

atic. In the first half, a connection between amāruk and [CT 44, 21; CTL 1, 81] reads ⸢e⸣-⸢te⸣-⸢qám⸣ ba-ab-la-ta). The

the Sumerian word for “flood,” amaru, and of both with reading of the present manuscript might have originated

the name of Tiāmat in Berossos, Omor(ō)ka, has been sug- in a misinterpretation of a suppositious e-tíq(ni). Both

gested repeatedly (Langdon 1907; Komoróczy 1973, 132 f.; etēqa(m) and enēna are best interpreted as infinitives.

Oshima 2003; see also George 2009, 23 f.), but is ill suited 57. Since bēlu is a vocative, the possessive suffix -šú

to the context. In the second half, the word abūšin is should be excised. The word appears as be-lu₄ in K.3158+

explained in synonym lists as abūbu, “flood” (see e. g. CAD (Lambert 1960b, pl. xii), but as an-ḫu (a corruption of

A/1, 93a). Lambert (2011; 2013, 473) suggests that an original d+en) in BM 45618 (Oshima 2011, iv–v and CTL 1, 86).

abūruk, written a-bu-ruk and somehow derived from abāru, 62. Because of the parallelism with l. 64 (ana ardīka),

“strength,” was understood as a-bu-šin and corrupted into e-la mu-tim-ma (thus written in all known manuscripts)33

a meaningless a-bu-ši-in by the copyists of the hymn and, should be parsed as ela mutim-ma, where mutu should be

subsequently, by Mesopotamian lexicographers. taken as “man” and ela, rather than the preposition “apart

9//11. The reading of the first part of the line is prob- from”, as a poetic form of the preposition eli.

lematic. The very late manuscript BM 45746 (Oshima 2011, 68 and 78. Note the anaptyctic vowel of the noun bēlu

pls. vi-vii; CTL 1, 85, dated 35 BCE) reads [dama]r.utu ⸢di⸣- in its status pronominalis (on which see George 2003, 432),

riš-ti, which was persuasively interpreted by Mayer (2014a, attested in all manuscripts that preserve the word.

396; 2016, 202) as a hapax legomenon dirištu (from darāsu): 73. The first word appears in the OB MS BM 78278 (CT

dirišti ug-gu-uk(-ka) teleʼʼi kâša, “wen dein Zorn niederge- 44, 21; CTL 1, 81) as na-ṣa-rum, but in most first-millen-

treten/niedergestreckt hat, dem kannst du (auch wieder) nium manuscripts (BM 76492 [Oshima 2011, pl. ii and CTL

aufhelfen.” The i of the new manuscript makes this inter- 1, 84], BM 45618 [Oshima 2011, iv–v and CTL 1, 86], and BM

pretation uncertain, for a writing di-i-riš-ti would be entirely 54980 [CTL 1, 93]) as a-za-ri. A mixed reading, a-na-za-ri,

unusual in an otherwise well-written NB manuscript. is attested in BM 45746 (Oshima 2011, pls. vi-vii; CTL 1, 85).

The tentative interpretation offered here is based on the

fact that the word kī can appear in late manuscripts written

just as ki,31 which suggests that the ⸢di⸣ of BM 45746, a man-

32 E. g. l. 4 kab-tat-{ta}-tuk 7 〈a〉-ma-r[u-uk] ll. 10//12 {a} a-bi, l. 15 〈ka〉

šèr-tu₄ … ba-bal!.

33 The writing e-la mu-tim-mu of MS BM 45618 (Oshima 2011, iv–v

and CTL 1, 86) is a Late Babylonian spelling. Compare the same writ-

31 Pace de Zorzi (2016). Thus appears e. g. in two Arsacid manu- ing -mu in the ‘Theodicy Commentary’ r 29′ (Jiménez 2017b: li-it-mu-

scripts (both unpublished, one of them belongs to the same man- um-mu for li-it-mu-um-ma [litmun-ma] in ‘Theodicy’ 255, Lambert

uscript as BM 45746) of ‘Marduk 1’ l. 100: šá-kin ki dum-qí, but ki-i 1960a, 86) and the other examples quoted by George 2003, 441 and

dumqi in K.3186+ (Lambert 1960b, pl. xiii). fn. 40.

�174 Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I

The meaning adopted here is based on the fact that, in an 146. The only other manuscript to preserve the last

OB document, (ḫ)azāru(m) appears in a position occupied word, K.3158+ (Lambert 1960b, pl. xv), reads it as lib-bu-

by salāmu(m), “to reconcile,” in other texts (Wilcke 1985, uk-ka.

261 fn. 68).34 147. K.3158+ (Lambert 1960b, pl. xv) and an unpub-

The second word, up-pu-ú (thus written in all manu- lished Arsacid manuscript read here li-kil-ka. The prefix

scripts) is probably apû D (also Oshima 2011, 179), but the lu- in the third person precative D and Š, typically an

meaning “to appear” (AHw. 1459b, Guichard 2014, 52) is ill Assyrianism, is not uncommon in N/LB texts (Woodington

suited to the context. The D stem of apû is almost exclu- 1982, 98–102).

sively attested in bilingual contexts as a translation of the 194. The word sag-tuk is thus written also in BM

Sumerian è. In such contexts, è is rendered either by uppû 76492 (Oshima 2011, pl. ii and CTL 1, 84), an Achaemenid

(e. g. Cohen 1988, 562 l. 135) or by padû, “to spare” (e. g. tablet otherwise free from corruptions.36 The word written

‘Udugḫul’ XIII–XV 36–37 [Geller 2016, 444 f.]). An ‘Eršema’ sag-tuk should mean “heart/liver” or “rage.”

contains, in fact both possibilities, if restored as u š₁₁ ĝ ì r i 199. The first word is preserved only in K.3175+

ĝ á m u - l u - r a n u - è - d è || imat zuqaqīpi ša amēla lā (Lambert 1960b, pl. xv): [o]-nu-ma. Lambert’s restoration

up-pu-u : lā i-pa-[du-ú], “the venom of a scorpion, which [e]-nu-ma (Lambert 1960b, 60) remains likely, although

does not uppû a man, (variant) does not sp[are]” (Gabbay it yields a non-trochaic ending (uballiṭu).37 If the recon-

2015, 315 l. a+3). It seems, therefore, advisable to assume struction of the second word is correct, K.3175+ (Lambert

the existence of a verb uppû, apparently D tantum, with 1960b, pl. xv) should be read as mi-t[u₄], which fits the

the meaning “to spare,” with which one may compare traces well. Compare K.81 (ABL 274) ll. 12–13: šá mi-i-tu

Arabic ʿafā (ʿfw), “to forgive.” a-na-ku ù šarru(lugal) bēlī(en-a) | ú-bal-liṭ-an-ni, “For I

74 and 78. The reading of the signs of the last word of was dead and the king, my lord, cured me.”

the line, preserved only in one late manuscript, is uncer- 200. Compare 82-3-23, 100 l. 5′ (George 1992, 227 f. and

tain. pl. 51): [… b]u-ʼ-a-ri a-na da-r[iš …].

141. The present manuscript solves the problematic 201//203. šūpâ might be an imperative (thus Mayer

reconstruction of the last word of the line.35 The verb is the 1996, 428) or a stative. In favor of the former interpreta-

poorly known kašû I in G stem (CAD K, 294a; AHw. 463a-b), tion speaks the ending -â; in favor of the latter a paral-

previously attested in two contexts with ep(e)ru, “dust”: (1) lel passage at the beginning of the ‘Seed of Kingship’ text

[s ù-s]ù = kašû ša sah ̮ ar in ‘Antagal’ D 247 (MSL 17, 207) (Lambert 1974, 435; Frame 1995, 25, now // BM 32507+ //

and (2) u₁₈ - l u i m - r i - a - b i l ú s a ḫ a r - r[a ! - k]e₄ ì-ni10-

i m IM 132614, both unpubl.), clearly connected to ‘Marduk 1’:

ni10-⸢e⸣ | šūtu ša ina zâqīšu nišī ⸢e⸣-p[e-r]u i-kaš-šu-⸢ú⸣, “the

south wind, which, when it blows, covers people with (1) z à - m í m[a ḫ ? - e o o] x x- m a n a m - m a ḫ - a - n i

dust” (‘Udugḫul’ XII 24, edited Geller 2016, 404; see also n a m - k a l a k i - š á r - r a u₄ - u l - d ù a - a - n i - š è

Jiménez 2013, 71 f.). The writing e-pe-er of MS Nin1 for ta-nit-[ti o o o o] x x x nar-bi-šú dan-nu-us-su šá kiš-

ep(e)ra is, however, unexpected in a Kuyunjik tablet. šá-ti ana u₄-mi ṣa-a-ti

144. The two manuscripts from Nineveh (K.3158+ (2) k á m ? - r i - a - b i [(o o )] x x x x- a k- a x- b i ì - l á - e

[Lambert 1960b, pl. xv] and K.8003 [ibid.: pl. xvi]) contain k a - t a r z i d u₁₁ - g a

a G stem (ipaššarkum-ma), whereas the present manu- uz-zu-u[š?-šú (?) o o] ki-ma a-bu!-bi na-as-ḫur-šú

script and another Sippar manuscript, BM 76492 (Oshima ṭa-a-bu šu-pa-a a-na da-la-li

2011, pl. ii, CTL no. 84), have a D stem (upaššarkum-ma). (3) k i t u š k i š u b [k]i - b i t i - l a - a n - n a [ø ù]ĝ

Both stems have the possible meaning “to expound.” bar-ra ba-ab -lá- e ĝiškim-bi ì-ma-al-la

šá šu-ud-du-u (ù) šu-šu-bu ba-šu-ú it-ti-šú aḫ-ra-taš

nišī(unmeš) kul-lu-mu na-ṣa-ar it-ti-šú

34 The verb azāru is explained in Malku V 86–87 both as kâšu, “to

help”, and rêmu, “to have mercy” (Hrůša 2010, 401). As noted by M.

Krebernik (private communication), both these meanings of ʿ-ḏ-r are

in fact attested in other Semitic languages: in Northwest Semitic lan-

guages and Old South Arabian ʿ-ḏ-r means “to help” (e. g. del Olmo

Lete/Sanmartín 2003, 153), whereas in Arabic ʿ-ḏ-r means “excuser

quelqu’un” (Biberstein-Kazimirski 1860, II 199b). 36 Cf. the interpretation “rest in your celebration” by Oshima (2011,

35 For previous reconstructions, see e. g. Labat 1939, 108 fn. 36 169), grammatically unconvincing.

(ka-[ti-im]), Seux 1976, 178 fn. 52 (ka-b[it-ta], followed by Groneberg 37 Note that the meaning “then” of enūma is “narrowly confined to

1987, II 118), and Oshima 2011, 185 (ka-š[i-i]). royal inscriptions, mostly Assyrian” (Moran 1988).

� Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I 175

(1) The praise of … […] … of his greatness, his universal, 205. On the second hemistich, compare ‘Enūma eliš’

eternal strength, II 58: bānû nēmeqi ilu Nudimmud, “the creator of wisdom,

(2) [His] rag[e is] like a flood, his attention is sweet, glori- the god Nudimmud.”

ous to praise, 206. On the verb krṭ or qrt, see Jiménez/Adalı (2015,

(3) In whose power it is to lay waste and to settle, to teach 178 f.). MS K.9430 (Lambert 1960b, pl. xv) reads here nak-

future people to watch for his sign. ru-ṭu, whereas MS BM 76492 (Oshima 2011, pl. ii and CTL 1,

84) reads [naq]-⸢ru-ta⸣. The present manuscript, however,

202. The various manuscripts preserve only meager preserves naqrāta, a very rare poetic form of the N infini-

remains of the first half of the line: before nišū, only K.7893 tive, instead of the normal nakruṭu/[naq]ruta of the other

(Lambert 1960b, pl. xv) preserves ⸢šá⸣?-[a-šú] (?). The first two manuscripts. On N infinitives of the naprāsu form, see

word has been tentatively restored after ‘Enūma eliš’ VI GAG § 56h and Kouwenberg (2010, 290 fn. 10).

136 šâšū-ma littaʼʼidāšu nišū aḫrâtaš, “let future people

praise only him!” Colophon. A Marduk-šāpik-zēri s. Ileʼʼi-Marduk is attested

On the use of “to discuss with each other” (nadānu in the colophon of IM 124472, a manuscript of the šuʼila

Št₂) in the meaning “to celebrate”, compare the ‘Gula ‘Marduk 29’ (unpubl., see Hilgert 2004, 333 f.). The scribe

Hymn’ ll. 6–7 (Lambert 1967, 116): ṭābat ḫissatī šulmu may be the same Nabû-tabni-uṣur s. Nabû-aplu-iddina

balāṭu | liptī (var. [l]ipittī) šulmu uš-ta-nam-da-na tenēšētu, d. Šangû-Akkad who copied IM 132543 (Fadhil/Hilgert

“Sweet is my praise, it is health and life, | my touching is 2008, dated Nbn 8 = 548 BCE), although the script of that

health; men discuss (it) with each other.” tablet is quite different. The name Nabû-tabni-uṣur is well

203. Traces of […]-ri (or […-a]r) are visible in the old attested in NB Sippar: compare Nabû-tabni-uṣur ṭupšarru

photograph. On the restoration, compare K.6395+ l. 4′ s. Mušēzib-Bēl d. Lūṣi-ana-nūr-Šamaš in BM 74970 (AH.83-

(BMS 52 = ‘Zappu 3’): én šar ilī gašrūti ša napḫar māti šūpû 1-18, 293) l. 15 (Nbk. 236) and Nabû-tabni-uṣur ṭupšarru

sebetti attunū-ma, “Kings of the mighty gods, who are s. Nabû-[…] d. Aškāpu! in BM 75603 (AH.83-1-18, 952) l. 16

manifest to the entire land, you are seven.” (Nbn. 95 [dated Nbn 3]), both Bongenaar 1997, 493.

Bibliography

al Rawi, F. N. H./A. R. George (2006): Tablets from the Sippar — (2008): The cultic lament ‘a gal-gal buru₁₄ su-su’ in a manuscript

Library XIII: Enūma Anu Ellil XX, Iraq 58, 23–57 from the ‘Sippar Library’, ZOrA 1, 154–193

Annus, A./A. Lenzi (2010): Ludlul bēl nēmeqi. The Standard — (2011): „Verwandelt meine Verfehlungen in Gutes!“ Ein šigû-Gebet

Babylonian poem of the righteous sufferer. SAACT 7. an Marduk aus dem Bestand der «Sippar-Bibliothek», in: G.

Helsinki Barjamovic [e. a.] (ed.), Akkade is king. A collection of papers

Ball, C. J. (1922): The Book of Job. Oxford by friends and colleagues presented to Aage Westenholz on

Biberstein-Kazimirski, A. D. (1860): Dictionnaire arabe-français. the occasion of his 70th birthday 15th of May 2009. PIHANS 118.

Paris Leiden, 93–109

Bongenaar, A. C. V. M. (1997): The Neo-Babylonian Ebabbar temple Frahm, E. (2011): Babylonian and Assyrian text commentaries.

at Sippar. Its administration and its prosopography. PIHANS Origins of interpretation. GMTR 5. Münster

80. Leiden Frame, G. (1995): Rulers of Babylonia from the Second Dynasty of

Borger, R. (1964): Review of Lambert Babylonian Wisdom Literature, Isin to the end of Assyrian domination (1157–612 B.C.). RIMB 2.

JCS 18, 49–56 Toronto, Buffalo, London

Cagni, L. (1969): L’Epopea di Erra. StSem 34. Rome Frazer, M. (2013): Nazi-Maruttaš in later Mesopotamian tradition,

Cohen, M. E. (1988): The canonical lamentations of ancient Kaskal 10, 187–220

Mesopotamia. Potomac, Maryland — (2015): Akkadian royal letters in later Mesopotamian tradition.

de Zorzi, N. (2016): Of pigs and workers. A note on Lugal-e and a Unpublished PhD dissertation

Late Babylonian commentary on Šumma ālu 49, NABU Gabbay, U. (2015): The Eršema prayers of the first millennium BC.

2016/79 HES 2. Wiesbaden

Ebeling, E. (21926): Babylonisch-assyrische Texte, in: H. Gressman Geller, M. J. (2016): Healing magic and evil demons. Canonical

(ed.), Altorientalische Texte und Bilder zum Alten Testamente. Udug-ḫul incantations. BAM 8. Berlin, New York

Zweite Auflage. Berlin, 108–449 George, A. R. (1992): Babylonian topographical texts. OLA 40. Leuven

Edzard, D. O. (1997): Gudea and his dynasty. RIME 3/1. Toronto, — (2003): The Babylonian Gilgamesh epic. Introduction, critical

Buffalo, London edition and cuneiform texts. Oxford

Fadhil, A./M. Hilgert (2007): Zur Identifikation des lexikalischen — (2009): Babylonian literary texts in the Schøyen Collection.

Kompendiums 2R 50+ (K 2035a + K 4337), RA 101, 95–105 CUSAS 10. Bethesda

�176 Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil and Enrique Jiménez, Literary Texts from the Sippar Library I

— (2015): The gods Išum and Ḫendursanga. Night watchmen and Lenzi, A. (2012): The curious case of failed revelation in Ludlul Bel

street-lighting in Babylonia, JNES 74, 1–8 Nemeqi. A new suggestion for the poem’s scholarly purpose,

George, A. R./F. N. H. al Rawi (1998): Tablets from the Sippar in: C. L. Crouch [e. a.] (ed.), Between heaven and earth.

Library VII: Three wisdom texts, Iraq 60, 187–206 Communication with the divine in the ancient Near East.

Gesche, P. D. (2001): Schulunterricht in Babylonien im ersten London, 36–66

Jahrtausend v. Chr. AOAT 275. Münster Lenzi, A. (2017): Review of Oshima, Babylonian poems of the righteous

Groneberg, B. (1987): Syntax, Morphologie und Stil der jungbabylo- sufferers, Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Studies 76, 180–187

nischen „hymnischen“ Literatur. FAOS 14. Stuttgart Mayer, W. R. (1980): „Ich rufe dich von ferne, höre mich von nahe!“

Guichard, M. (2014): L’épopée de Zimrī-Lîm. Florilegium Marianum Zu einer babylonischen Gebetsformel, in: R. Albertz [e. a.]

14. Paris (ed.), Werden und Wirken des Alten Testaments. Festschrift für

Hämeen-Anttila, J. (2000): A sketch of Neo-Assyrian grammar. SAAS Claus Westermann zum 70. Geburtstag. Göttingen, 302–317

13. Helsinki — (1990): Sechs Šu-ila-Gebete, Or. 59, 449–490

Hilgert, M. (2004): Bestand, Systematik und soziokultureller Kontext — (1996): Zum Pseudo-Lokativadverbialis im Jungbabylonischen,

einer neubabylonischen „Tempelbibliothek“. Ein Beitrag zur Or. 65, 428–434

altorientalischen Textsammlungstypologie. Habilitations- — (2007): Das akkadische Präsens zum Ausdruck der Nachzeitigkeit

schrift. Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena in der Vergangenheit, Or. 76, 117–144

Hrůša, I. (2010): Die akkadische Synonymenliste malku = šarru. Eine — (2014a): Nachlese, Or. 83, 380–406

Textedition mit Übersetzung und Kommentar. AOAT 50. Münster — (2014b): Review of Annus and Lenzi Ludlul bēl nēmeqi (SAACT 7),

Hurowitz, V. A. (2008): Tales of two sages. Towards an image of the Or. 83, 275–280

“wise man” in Akkadian writings, in: L. G. Perdue (ed.), Scribes, — (2015): Nachlese II: zu Wolfram von Soden, Grundriß der

sages, and seers. The sage in the Eastern Mediterranean world. akkadischen Grammatik (³1995), Or. 84, 177–216

Göttingen, 64–94 — (2016): Zum akkadischen Wörterbuch: A-L, Or. 85, 181–235

Jiménez, E. (2013): La imagen de los vientos en la literatura — (2017): Zum akkadischen Wörterbuch: Ṣ-Z, Or. 86, 202–252

babilónica. Unpublished PhD dissertation Moran, W. L. (1988): Enūma elîš I 1–8, NABU 1988/21

— (2014): New fragments of Gilgameš and other literary texts from Olmo Lete, G. del/J. Sanmartín (2003): A dictionary of the Ugaritic

Kuyunjik, Iraq 76, 99–121 language in the alphabetic tradition. HdO 67. Leiden

— (2017a): The Babylonian disputation poems. With editions of the Oshima, T. (2003): Some comments on Prayer to Marduk, no. 1, lines

Series of the Poplar, Palm and Vine, the Series of the Spider, 5/7, NABU 2003/99

and the Story of the Poor, Forlorn Wren. CHANE 87. Leiden — (2011): Babylonian prayers to Marduk. ORA 7. Tübingen

— (2017b): Commentary on Theodicy (CCP no. 1.4, http://ccp. — (2014): Babylonian poems of pious sufferers. Ludlul Bēl Nēmeqi

yale.edu/P404917), accessed June 27, 2017, Cuneiform and the Babylonian Theodicy. ORA 14. Tübingen

Commentaries Project Piccin, M./M. Worthington (2015): Schizophrenia and the problem of

Jiménez, E./S. F. Adalı (2015): The ‘Prostration Hemerology’ suffering in the Ludlul hymn to Marduk, RA 109, 113–124

revisited. An everyman’s hemerology at the king’s court, ZA Pongratz-Leisten, B. (2010): From ritual to text to intertext. A new look

105, 154–191 on the dreams in Ludlul Bēl Nēmeqi, in: P. Alexander [e. a.] (ed.),

Koch, U. S. (2005): Secrets of extispicy. The chapter Multābiltu of In the second degree. Paratextual literature in ancient Near

the Babylonian extispicy series and Niṣirti bārûti texts mainly Eastern and ancient Mediterranean culture. Leiden, 139–157

from Aššurbanipal’s library. AOAT 326. Münster Seux, M.-J. (1976): Hymnes et prières aux dieux de Babylonie et

Komoróczy, G. (1973): Berosos and the Mesopotamian literature, d’Assyrie. Paris

AcAntHung 21, 125–152 Soden, W. von (1971): Der große Hymnus an Nabû, ZA 61, 44–71

Kouwenberg, N. J. C. (1997): Gemination in the Akkadian verb. SSN — (1990): Der leidende Gerechte, in: O. Kaiser (ed.), Weisheitstexte,

33. Assen Mythen und Epen. Weisheitstexte I. Texte aus der Umwelt des

— (2010): The Akkadian verb and its Semitic background. Winona Alten Testaments 3/1. 110–135

Lake Streck, M. P. (2017): The terminology for times of the day in

Labat, R. (1939): Le caractère religieux de la royauté assyro-baby- Akkadian, in: Y. Heffron [e. a.] (ed.), At the dawn of history.

lonienne. Paris Ancient Near Eastern studies in honour of J. N. Postgate.

Lambert, W. G. (1960a): Babylonian wisdom literature. Oxford Winona Lake, 583–609

— (1960b): Three literary prayers of the Babylonians, AfO 19, Thompson, R. C. (1910): The third tablet of the series Ludlul Bêl

47–66 Nimeḳi, PSBA 32, 18–24

— (1967): The Gula hymn of Bulluṭsa-rabi, Or. 36, 105–132 Wasserman, N. (2016): Akkadian love literature of the third and

— (1974): The seed of kingship, in: P. Garelli (ed.), Le palais et la second millennium BCE. LAOS 4. Wiesbaden

royauté (archéologie et civilisation). Paris, 427–444 Wilcke, C. (1985): Familiengründung im alten Babylonien, in: E. W.

— (1995): Some new Babylonian wisdom literature, in: J. Day [e. Müller (ed.), Geschlechtsreife und Legitimation zur Zeugung.

a.] (ed.), Wisdom in ancient Israel. Essays in honour of J. A. Freiburg, 213–317

Emerton. Cambridge, 30–42 Woodington, N. R. (1982): A grammar of the Neo-Babylonian letters

— (2011): Notes on malku = šarru, NABU 2011/28 of the Kuyunjik collection. Unpublished PhD dissertation

— (2013): Babylonian creation myths. MC 16. Winona Lake Zgoll, A. (2006): Königslauf und Götterrat. Struktur und Deutung des

Langdon, S. (1907): Abūbu und amāruku, ZA 20, 450–452 babylonischen Neujahrsfestes, in: E. Blum/R. Lux (ed.), Festtra-

Leichty, E. [e. a.] (1988): Catalogue of the Babylonian tablets in the ditionen in Israel und im Alten Orient. WWGTh 28. Gütersloh,

British Museum. Volume VIII: Tablets from Sippar 3. London 11–80

�

Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil

Anmar Abdulillah Fadhil