Help Desk

Technical resources and FAQs for climate adaptation

Don't see what you need? Submit a question to the form below.

Help Desk Items

Technical Resources

FAQs

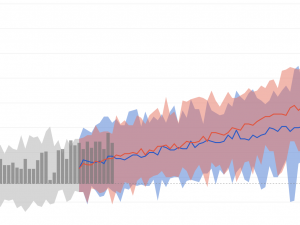

A good place to start is with the CMRA Assessment Tool. Data and maps available in this tool are downscaled results from global climate models. Results for selected geographies indicate how severity and frequency of five common climate-related hazards is projected to change through this century.

The timeframe for evaluating climate change projections depends on the longevity of the decision you are making. For example, the lifespan of built infrastructure may be subject to climate-related impacts decades into the future. Such decisions often involve substantial investment, which itself elevates the risk imposed by climate change.

Alternatively, a given policy may be in effect for a shorter period of time. When addressing urban flooding impacts on roads or infrastructure within the context of a local comprehensive plan, decision makers are likely concerned with a 10-year horizon.

Representative concentration pathways (RCPs) portray possible future greenhouse gas and aerosol concentration scenarios. Scenarios do not substantially differ before mid-century. Because the concentrations of those gases continue to increase at a rapid rate, and because planners want to incorporate a margin of safety in their plans, many professionals use RCP 8.5 for near and long-term projections. For examples of how one state evaluates and uses projections, see Cal-Adapt.

Technical Resources

FAQs

Vulnerability is the propensity or predisposition of assets to be adversely affected by hazards. Vulnerability encompasses exposure, sensitivity, potential impacts, and adaptive capacity. Because these factors vary, not all communities or populations are equally vulnerable to the same climate risks.

Assets include the people, resources, ecosystems, infrastructure, and the services they provide. Assets are the tangible and intangible things communities value and will vary by community.

The Steps to Resilience – Assess Vulnerability & Risk can help practitioners think through the full range of asset categories that may be relevant for their community.

Risk is the potential for negative consequences where something of value is at stake. In the context of assessing climate impacts, risk refers to the potential for adverse consequences of a climate-related hazard. Risk can be assessed by multiplying the probability of a hazard by the magnitude of the negative consequence or loss.

For example, the risk of extreme heat exposure to a subsection of a city's population might be evaluated by examining projections of extreme heat and the number and sensitivity of people or other assets that are potentially exposed to extreme heat events. Evaluating sensitivity could entail identifying populations that may be particularly sensitive to heat, identifying housing stock with poor or no climate control, and/or identifying whether there are sufficient cooling centers to assist those without access to cooling at home.

When evaluating community actions (e.g., projects, capital improvements, facilities siting and maintenance), you can apply a "climate lens" or evaluation assessment tool and integrate it into standard operating procedures. This could become a required or recommended part of how your organization or agency completes a permitting or financing process. The Steps to Resilience: Prioritize & Plan can help you evaluate the costs, benefits, and your team’s capacity to implement each potential solution.

Another example of such a tool is the Climate Change Adaptation Certification Tool. This tool asks simple questions to quickly guide users through an evaluation to make a decision about the project’s suitability in the context of climate change risks and helps the user think through modifications needed to address identified risks.

Technical Resources

FAQs

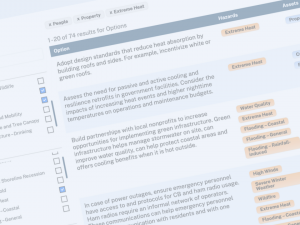

The Options Database contains over a thousand resilience-building solutions considered by other communities. To see examples of adaptation strategies in practice, explore the Climate Adaptation Knowledge Exchange and the Climate Resilience Toolkit case study libraries. For examples specifically focused on state and local adaptation policy, explore the Adaptation Clearinghouse.

Understand your community's vulnerabilities, then design strategies to reduce those vulnerabilities and increase your ability deliver on services, protect assets, and provide actionable outcomes.

The Steps to Resilience: Investigate Options can help you compile an extensive list of actions that could reduce your current vulnerabilities and risk.

The Steps to Resilience Training is a six-module e-learning course designed to help practitioners lead local resilience efforts. The best way to receive updates about future trainings is to join the Climate Smart Communities mailing list. In the meantime, if you’d like to know more about the Steps to Resilience, there is a great overview on the Climate Resilience Toolkit.

Technical Resources

FAQs

An adaptation process requires the people who will lead the process, the people who will implement it, and the people who will be affected by it. Those three groups are not necessarily mutually exclusive, but they all need to be participants and ideally co-developers. It is very beneficial to have the a broad range of perspectives and experiences in your process to ensure all groups are properly represented.

Learn more about how to build your team using the Steps to Resilience: Get Started »

An Adaptation Plan may overlap with a Hazard Mitigation Plan (HMP) or a Climate Action Plan (CAP), but they are not always the same.

HMPs focus on preventing harm to people and property based on past disturbances, but may not fully account for likely future climate conditions. CAPs often emphasize reducing greenhouse gas emissions rather than preparing for climate-related impacts. Adaptation Plans typically address a full range of climate-related impacts (including future conditions); chronic and secondary effects on human systems such as health, infrastructure, and the economy; and natural systems.

Technical Resources

FAQs

Adaptation actions should be implemented through the same processes other actions are taken in your community. Ideally you should mainstream adaptation into the practices your community has found to be effective in engaging community members, complying with regulatory requirements, securing funding, and ensuring sustainability.

There are a number of large federal programs that are often used to fund adaptation implementation, such as FEMA's Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) grants, funding can also be available through state agencies, private foundations, and increasingly through private investment. Municipal bonds are often used, particularly when the resilience project is infrastructure-focused. See also the "financing adaptation" FAQs for more information.

Technical Resources

FAQs

One potential solution is to find a partner! Possibilities include a university or citizen science (CS) partner. Interest in learning about adaptation outcomes is growing. You may be able to entice a researcher at a local college, university or even high school to assess the outcomes of your actions. In many cases they are well positioned as fellow long-term local residents. These partners may be able to work independently and share results on a regular basis. There are also some national groups interested in these questions.

Another approach is using CS citizen science to build capacity for monitoring adaptation. By involving citizens directly in the research process, CS can help generate information and insights valuable to monitoring and evaluating effectiveness. CS can also have valuable co-benefits of building community, empowerment, and political capital for creating change by raising awareness about local-scale risks while facilitating the development and knowledge of adaptive measures by individuals and communities. CS has the potential to address some of the key challenges that hinder citizen engagement, particularly if such programs are created in ways that minimize barriers to participation and allow for two-way exchange of knowledge so that community members are both learning from and contributing to knowledge goals and outcomes. It should be noted that unless there is a good local partner to lead a CS effort, this can be a significant initial investment of effort to get off the ground, but if it works it can be self sustaining.

You are best prepared to judge the effectiveness of adaptation actions if you build in a monitoring and evaluation framework that enables tracking and reporting of key metrics about your adaptation actions, climate variables, and community outcomes such as public health or emergency response efforts. The metrics assembled and tracked will depend on the actions taken.

Examples include: tracking emergency response costs to flooding before, during, and after implementation of flood mitigation actions and flood events; tracking emergency room visits in parallel with implementation of cooling centers and extreme heat events.

The practice of climate change adaptation has an incredible opportunity to learn what is working and to improve over time. An analogy can be drawn to the field of medicine where researchers carefully study the conditions under which certain interventions are successful or not. For adaptation, this requires that communities that are planning and implementing adaptation measures monitor and report on what they have done and the outcomes that were associated with their actions. Over time, the results from this information can be used to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of adaptation, thereby saving scarce resources for communities such as yours.

Technical Resources

FAQs

Community engagement can help build the political capital and human resources you need for successful design and implementation of a plan; it also can be very difficult to come by as many people are limited in their willingness and ability to participate, and this can especially be true of overburdened communities. Consider approaches that reduce barriers to participation: this can include providing stipends for community members to participate in meetings or focus groups; offering child care during events; offering events at a variety of times; and creating outreach to public events and locations such as neighborhood association meetings and community centers in order to meet people where they are already at.

There are good models available for designing community meetings. One example is the Strong, Prosperous, and Resilient Communities Challenge (SPARCC) guide for community engagement, which lays out key principles and provides several case studies for successfully structuring community engagement.

Good practice in community engagement that entices broader participation includes some time tested approaches, such as:

- Develop relationships with local leaders from the populations you are trying to engage and include them in the planning and leadership of the local climate adaptation process.

- Meet people where they are to build awareness and interest in opportunities to engage; social media, direct marketing, and tabling at community events are all good ways to engage people in conversation and encourage participation.

Technical Resources

FAQs

“Nature-based Solutions” (NbS) describes the potential for natural systems to provide a diverse array of benefits, including pollution reduction and natural buffers for climate-related hazards. NbS can encompass a wide range of options, from reliance on still-intact natural systems and restoration of key ecosystems to the use of engineered systems designed to emulate natural system functions, for example, rain gardens for managing stormwater or urban tree planting to mitigate urban heat islands.

Nature-based solutions have several potential advantages over gray (engineered, human-made) infrastructure, including: co-benefits not present with gray infrastructure, such as provisioning habitat, increasing biodiversity, and having aesthetic qualities. If constructed appropriately, nature-based solutions have the capacity to be self-regulating and respond and adjust to change, (e.g., a vegetative community whose members can shift in relative dominance over time in response to changing weather conditions; marsh vegetation that can trap sediment and build upon itself, adding capacity for resilience to sea level rise).

The somewhat unsatisfactory answer is "it depends". Scale and location matter significantly with NbS solutions. Grey infrastructure, such as seawalls or dams, can have much higher capital costs at the front end for permitting and construction, relative to NbS. NbS can require larger land footprints than grey infrastructure to achieve desired benefits, so costs could be significant where land value is high. It is important to understand the opportunity costs of implementing NbS when other land uses are in consideration (e.g., agricultural or urban development). Planning for NbS should also take into consideration ongoing maintenance costs (e.g., irrigation or fertilizer to establish plantings, ongoing mowing or weeding to maintain desired vegetation assemblages).

Technical Resources

FAQs

There are a number of large federal programs that are often used to fund adaptation projects, such as FEMA's Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) grants, funding can also be available through state agencies, private foundations, and increasingly through private investment. Municipal bonds are often used, particularly when the resilience project is infrastructure-focused.

While funding is available for a wide variety of projects and processes, finding funding is facilitated when projects:

- have clearly-defined outcomes that are expected to lead to increased resilience,

- include a robust community engagement plan,

- explicitly incorporate consideration of equity throughout the process, and

- prioritize nature-based solutions.

Explore the Ready-to-Fund Resilience Toolkit here.

Unfortunately, there is not yet a single searchable resource to help find funding sources. However, for infrastructure-based projects, there is a searchable resource, the Local Infrastructure Hub, to help communities find funding resources related to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. The Ready-to-Fund Resilience Toolkit also has many useful resources.

NOAA Climate Adaptation Partnerships (CAP) may have resources available. For example, the Northwest Climate Resilience Collaborative awarded community grants in 2023 to support justice-focused, environmental, and climate projects that advance community-centered resilience priorities. Check with your regional CAP program to see if there are current funding opportunities available.

Technical Resources

FAQs

A good place to start is with the CMRA Assessment Tool. Data and maps available in this tool are downscaled results from global climate models. Results for selected geographies indicate how severity and frequency of five common climate-related hazards is projected to change through this century.

The timeframe for evaluating climate change projections depends on the longevity of the decision you are making. For example, the lifespan of built infrastructure may be subject to climate-related impacts decades into the future. Such decisions often involve substantial investment, which itself elevates the risk imposed by climate change.

Alternatively, a given policy may be in effect for a shorter period of time. When addressing urban flooding impacts on roads or infrastructure within the context of a local comprehensive plan, decision makers are likely concerned with a 10-year horizon.

Representative concentration pathways (RCPs) portray possible future greenhouse gas and aerosol concentration scenarios. Scenarios do not substantially differ before mid-century. Because the concentrations of those gases continue to increase at a rapid rate, and because planners want to incorporate a margin of safety in their plans, many professionals use RCP 8.5 for near and long-term projections. For examples of how one state evaluates and uses projections, see Cal-Adapt.

Technical Resources

FAQs

Vulnerability is the propensity or predisposition of assets to be adversely affected by hazards. Vulnerability encompasses exposure, sensitivity, potential impacts, and adaptive capacity. Because these factors vary, not all communities or populations are equally vulnerable to the same climate risks.

Assets include the people, resources, ecosystems, infrastructure, and the services they provide. Assets are the tangible and intangible things communities value and will vary by community.

The Steps to Resilience – Assess Vulnerability & Risk can help practitioners think through the full range of asset categories that may be relevant for their community.

Risk is the potential for negative consequences where something of value is at stake. In the context of assessing climate impacts, risk refers to the potential for adverse consequences of a climate-related hazard. Risk can be assessed by multiplying the probability of a hazard by the magnitude of the negative consequence or loss.

For example, the risk of extreme heat exposure to a subsection of a city's population might be evaluated by examining projections of extreme heat and the number and sensitivity of people or other assets that are potentially exposed to extreme heat events. Evaluating sensitivity could entail identifying populations that may be particularly sensitive to heat, identifying housing stock with poor or no climate control, and/or identifying whether there are sufficient cooling centers to assist those without access to cooling at home.

When evaluating community actions (e.g., projects, capital improvements, facilities siting and maintenance), you can apply a "climate lens" or evaluation assessment tool and integrate it into standard operating procedures. This could become a required or recommended part of how your organization or agency completes a permitting or financing process. The Steps to Resilience: Prioritize & Plan can help you evaluate the costs, benefits, and your team’s capacity to implement each potential solution.

Another example of such a tool is the Climate Change Adaptation Certification Tool. This tool asks simple questions to quickly guide users through an evaluation to make a decision about the project’s suitability in the context of climate change risks and helps the user think through modifications needed to address identified risks.

Technical Resources

FAQs

The Options Database contains over a thousand resilience-building solutions considered by other communities. To see examples of adaptation strategies in practice, explore the Climate Adaptation Knowledge Exchange and the Climate Resilience Toolkit case study libraries. For examples specifically focused on state and local adaptation policy, explore the Adaptation Clearinghouse.

Understand your community's vulnerabilities, then design strategies to reduce those vulnerabilities and increase your ability deliver on services, protect assets, and provide actionable outcomes.

The Steps to Resilience: Investigate Options can help you compile an extensive list of actions that could reduce your current vulnerabilities and risk.

The Steps to Resilience Training is a six-module e-learning course designed to help practitioners lead local resilience efforts. The best way to receive updates about future trainings is to join the Climate Smart Communities mailing list. In the meantime, if you’d like to know more about the Steps to Resilience, there is a great overview on the Climate Resilience Toolkit.

Technical Resources

FAQs

An adaptation process requires the people who will lead the process, the people who will implement it, and the people who will be affected by it. Those three groups are not necessarily mutually exclusive, but they all need to be participants and ideally co-developers. It is very beneficial to have the a broad range of perspectives and experiences in your process to ensure all groups are properly represented.

Learn more about how to build your team using the Steps to Resilience: Get Started »

An Adaptation Plan may overlap with a Hazard Mitigation Plan (HMP) or a Climate Action Plan (CAP), but they are not always the same.

HMPs focus on preventing harm to people and property based on past disturbances, but may not fully account for likely future climate conditions. CAPs often emphasize reducing greenhouse gas emissions rather than preparing for climate-related impacts. Adaptation Plans typically address a full range of climate-related impacts (including future conditions); chronic and secondary effects on human systems such as health, infrastructure, and the economy; and natural systems.

Technical Resources

FAQs

Adaptation actions should be implemented through the same processes other actions are taken in your community. Ideally you should mainstream adaptation into the practices your community has found to be effective in engaging community members, complying with regulatory requirements, securing funding, and ensuring sustainability.

There are a number of large federal programs that are often used to fund adaptation implementation, such as FEMA's Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) grants, funding can also be available through state agencies, private foundations, and increasingly through private investment. Municipal bonds are often used, particularly when the resilience project is infrastructure-focused. See also the "financing adaptation" FAQs for more information.

Technical Resources

FAQs

One potential solution is to find a partner! Possibilities include a university or citizen science (CS) partner. Interest in learning about adaptation outcomes is growing. You may be able to entice a researcher at a local college, university or even high school to assess the outcomes of your actions. In many cases they are well positioned as fellow long-term local residents. These partners may be able to work independently and share results on a regular basis. There are also some national groups interested in these questions.

Another approach is using CS citizen science to build capacity for monitoring adaptation. By involving citizens directly in the research process, CS can help generate information and insights valuable to monitoring and evaluating effectiveness. CS can also have valuable co-benefits of building community, empowerment, and political capital for creating change by raising awareness about local-scale risks while facilitating the development and knowledge of adaptive measures by individuals and communities. CS has the potential to address some of the key challenges that hinder citizen engagement, particularly if such programs are created in ways that minimize barriers to participation and allow for two-way exchange of knowledge so that community members are both learning from and contributing to knowledge goals and outcomes. It should be noted that unless there is a good local partner to lead a CS effort, this can be a significant initial investment of effort to get off the ground, but if it works it can be self sustaining.

You are best prepared to judge the effectiveness of adaptation actions if you build in a monitoring and evaluation framework that enables tracking and reporting of key metrics about your adaptation actions, climate variables, and community outcomes such as public health or emergency response efforts. The metrics assembled and tracked will depend on the actions taken.

Examples include: tracking emergency response costs to flooding before, during, and after implementation of flood mitigation actions and flood events; tracking emergency room visits in parallel with implementation of cooling centers and extreme heat events.

The practice of climate change adaptation has an incredible opportunity to learn what is working and to improve over time. An analogy can be drawn to the field of medicine where researchers carefully study the conditions under which certain interventions are successful or not. For adaptation, this requires that communities that are planning and implementing adaptation measures monitor and report on what they have done and the outcomes that were associated with their actions. Over time, the results from this information can be used to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of adaptation, thereby saving scarce resources for communities such as yours.

Technical Resources

FAQs

Community engagement can help build the political capital and human resources you need for successful design and implementation of a plan; it also can be very difficult to come by as many people are limited in their willingness and ability to participate, and this can especially be true of overburdened communities. Consider approaches that reduce barriers to participation: this can include providing stipends for community members to participate in meetings or focus groups; offering child care during events; offering events at a variety of times; and creating outreach to public events and locations such as neighborhood association meetings and community centers in order to meet people where they are already at.

There are good models available for designing community meetings. One example is the Strong, Prosperous, and Resilient Communities Challenge (SPARCC) guide for community engagement, which lays out key principles and provides several case studies for successfully structuring community engagement.

Good practice in community engagement that entices broader participation includes some time tested approaches, such as:

- Develop relationships with local leaders from the populations you are trying to engage and include them in the planning and leadership of the local climate adaptation process.

- Meet people where they are to build awareness and interest in opportunities to engage; social media, direct marketing, and tabling at community events are all good ways to engage people in conversation and encourage participation.

Technical Resources

FAQs

“Nature-based Solutions” (NbS) describes the potential for natural systems to provide a diverse array of benefits, including pollution reduction and natural buffers for climate-related hazards. NbS can encompass a wide range of options, from reliance on still-intact natural systems and restoration of key ecosystems to the use of engineered systems designed to emulate natural system functions, for example, rain gardens for managing stormwater or urban tree planting to mitigate urban heat islands.

Nature-based solutions have several potential advantages over gray (engineered, human-made) infrastructure, including: co-benefits not present with gray infrastructure, such as provisioning habitat, increasing biodiversity, and having aesthetic qualities. If constructed appropriately, nature-based solutions have the capacity to be self-regulating and respond and adjust to change, (e.g., a vegetative community whose members can shift in relative dominance over time in response to changing weather conditions; marsh vegetation that can trap sediment and build upon itself, adding capacity for resilience to sea level rise).

The somewhat unsatisfactory answer is "it depends". Scale and location matter significantly with NbS solutions. Grey infrastructure, such as seawalls or dams, can have much higher capital costs at the front end for permitting and construction, relative to NbS. NbS can require larger land footprints than grey infrastructure to achieve desired benefits, so costs could be significant where land value is high. It is important to understand the opportunity costs of implementing NbS when other land uses are in consideration (e.g., agricultural or urban development). Planning for NbS should also take into consideration ongoing maintenance costs (e.g., irrigation or fertilizer to establish plantings, ongoing mowing or weeding to maintain desired vegetation assemblages).

Technical Resources

FAQs

There are a number of large federal programs that are often used to fund adaptation projects, such as FEMA's Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) grants, funding can also be available through state agencies, private foundations, and increasingly through private investment. Municipal bonds are often used, particularly when the resilience project is infrastructure-focused.

While funding is available for a wide variety of projects and processes, finding funding is facilitated when projects:

- have clearly-defined outcomes that are expected to lead to increased resilience,

- include a robust community engagement plan,

- explicitly incorporate consideration of equity throughout the process, and

- prioritize nature-based solutions.

Explore the Ready-to-Fund Resilience Toolkit here.

Unfortunately, there is not yet a single searchable resource to help find funding sources. However, for infrastructure-based projects, there is a searchable resource, the Local Infrastructure Hub, to help communities find funding resources related to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. The Ready-to-Fund Resilience Toolkit also has many useful resources.

NOAA Climate Adaptation Partnerships (CAP) may have resources available. For example, the Northwest Climate Resilience Collaborative awarded community grants in 2023 to support justice-focused, environmental, and climate projects that advance community-centered resilience priorities. Check with your regional CAP program to see if there are current funding opportunities available.