(© pict rider - stock.adobe.com)

Cambridge Researcher’s Review Challenges Ideas About Where Awareness Begins

In A Nutshell

- A Cambridge researcher’s review suggests the brain’s ancient subcortex may be sufficient for behaviours that imply basic consciousness.

- Stimulation studies show subcortical regions profoundly affect awareness, while cortical effects are less decisive.

- Cases of brain injury and animal experiments show awareness-like behaviours can persist without the cortex.

- The findings could reshape medical practice, with greater attention to subcortical integrity in patients with brain injuries.

CAMBRIDGE, England — For decades, many scientists assumed that human consciousness depends mainly on the brain’s newest and most complex regions. A wide-ranging review by Peter Coppola, a researcher at the University of Cambridge, suggests otherwise: awareness may rest on the brain’s oldest structures.

Coppola analyzed over a century of research, drawing together results from neuroimaging, stimulation studies, neurological case reports, and animal experiments. His findings, published in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, suggest that rather than being a uniquely human phenomenon, consciousness may stem from brain machinery that predates mammals by hundreds of millions of years. This raises the possibility that forms of experience extend across a wider range of animals than previously acknowledged.

What Brain Stimulation Studies Reveal

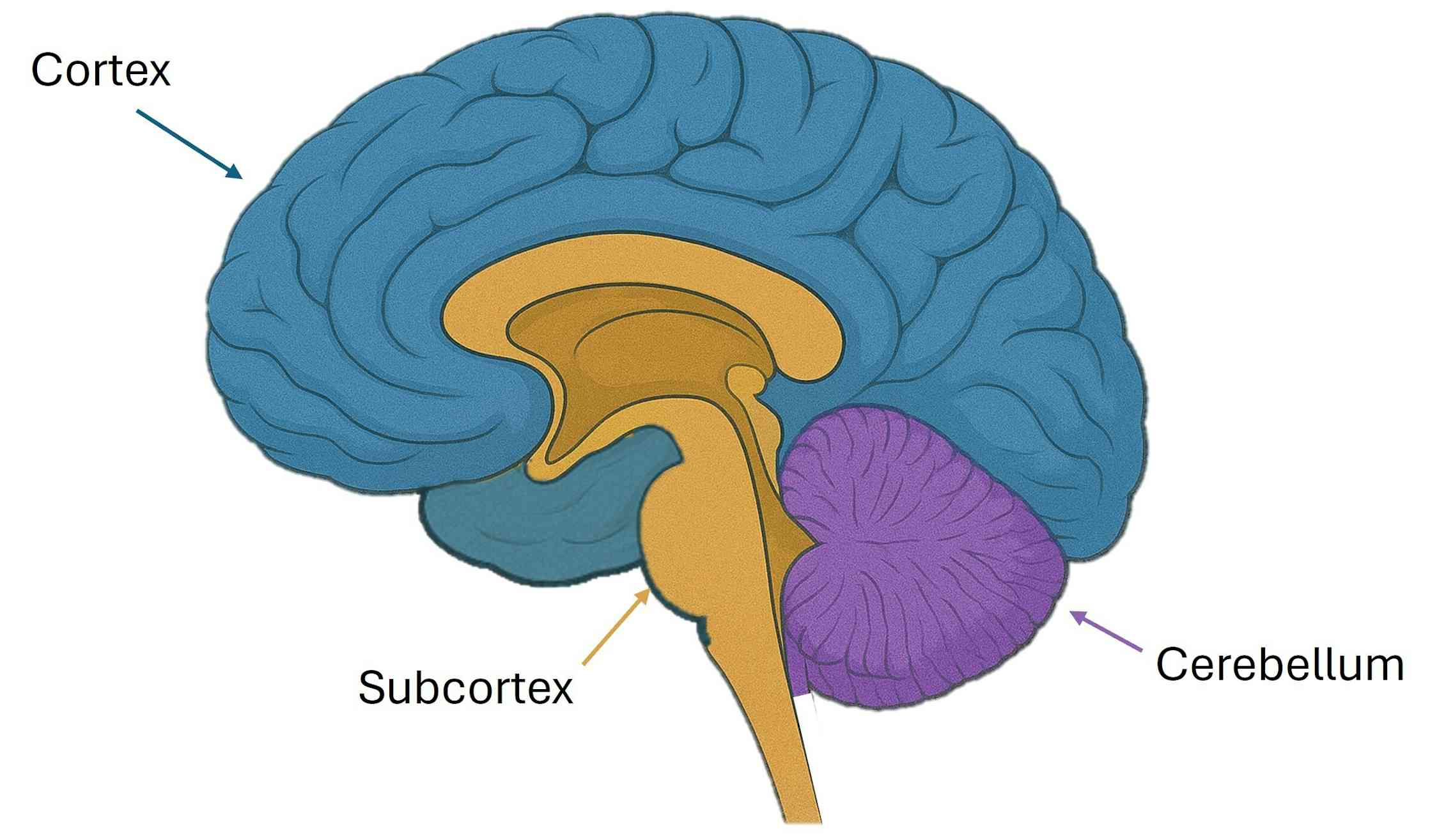

In an article published by The Conversation, Coppla writes: “The leading theories of consciousness suggest that the outer layer of the human brain, called the cortex, is fundamental to consciousness.” The prefrontal cortex, with its role in planning and self-awareness, long seemed like the obvious candidate. But Coppola highlights that the subcortex “has not changed much in the last 500 million years. It is thought to be like electricity for a TV, necessary for consciousness, but not enough on its own.”

When Coppola reviewed studies that altered brain activity through electrical or magnetic stimulation, he found distinct patterns. “Changing the activity of the neocortex can change your sense of self, make you hallucinate, or affect your judgment,” he writes. But altering deeper regions had more dramatic consequences: “Changing the subcortex may have extreme effects. We can induce depression, wake a monkey from anaesthesia or knock a mouse unconscious.”

Even the cerebellum, once dismissed as irrelevant, can influence awareness. Stimulation studies showed changes in conscious perception when this region was activated, suggesting a more complex picture in which several brain systems interact.

Primitive Feelings as Building Blocks of Awareness

The subcortex, often referred to as our “lizard brain,” is deeply involved in monitoring survival states: hunger, thirst, pain, pleasure, and fear. These give rise to what neuroscientists call “primary affects”—the raw feelings that motivate behavior across species. Coppola explains that “such fundamental subcortical responses mediate reinforcement learning in the environment and can therefore lead to relatively complex behaviors.”

This suggests that consciousness at its root may not involve lofty reasoning or narrative selfhood. Instead, it may begin with the simple sense of “what it is like” to feel. The cortex then elaborates on this foundation, adding language, planning, memory, and abstraction. Coppola emphasizes that this does not mean the cortex is irrelevant, but rather that it may not be the sole birthplace of consciousness.

Lessons From Brain Injury Cases

Coppola also examined neurological evidence from both humans and animals. Severe cortical damage can impair awareness, but in some cases, basic signs of experience remain. By contrast, damage to key subcortical regions, especially in the brainstem and thalamus, is strongly linked to unconsciousness or death.

Still, Coppola cautions that the picture is complicated. Reported cases of coma after “diffuse bilateral destruction of the cortex” often involve underlying causes, such as metabolic failure or toxins, that also impair deeper brain regions. In other words, it is not clear that cortical loss alone abolishes consciousness.

He points to rare but striking cases of children born with hydranencephaly, a condition that leaves them without most of the cortex. “According to medical textbooks, these people should be in a permanent vegetative state. However, there are reports that these people can feel upset, play, recognize people or show enjoyment of music,” Coppola writes.

Animal experiments add further weight. “Across mammals — from rats to cats to monkeys — surgically removing the neocortex leaves them still capable of an astonishing number of things. They can play, show emotions, groom themselves, parent their young and even learn,” Coppola observes. “Surprisingly, even adult animals that underwent this surgery showed similar behavior.”

While these behaviors are less sophisticated than those of intact animals, they suggest that some form of conscious experience may persist without the cortex. Coppola is careful, however, to phrase this in terms of behaviors that indicate experience, since subjective awareness itself cannot be measured directly.

Rethinking Human Uniqueness

These findings challenge the traditional hierarchy that places human awareness far above that of other animals. If the most basic forms of consciousness stem from brain structures we share with reptiles and fish, then the line between human and animal awareness may be thinner than long assumed.

Still, Coppola stresses that human consciousness is not reduced to something primitive. The cortex enriches the basic subcortical platform with extraordinary features: moral reasoning, artistic creativity, language, and the sense of a personal narrative. What his review highlights is that the foundation of awareness itself may be ancient and widely shared.

As he writes: “Different authors have thought that such basic feelings were the first experiences to be engendered in the history of our world, and perhaps the ‘lowest level of consciousness.’”

Implications for Medicine

This shift in perspective carries medical significance. Doctors often focus on cortical activity when evaluating whether patients with severe brain injuries are conscious. Coppola’s review suggests that subcortical integrity may be just as critical, if not more so.

This raises pressing ethical questions. If some patients diagnosed as being in a vegetative state retain subcortical function, they may have rudimentary awareness that current tests overlook. Recognizing this possibility could influence both treatment strategies and end-of-life decisions.

A Broader Perspective

Rather than treating consciousness as a modern achievement tied only to our advanced cortex, Coppola’s review invites us to see it as evolution’s deep-rooted solution to the challenge of guiding behavior. The cortex builds on this with complexity and refinement, but the essential spark of awareness may rest in older brain circuits.

Publication Information

“A review of the sufficient conditions for consciousness” by Peter Coppola appeared in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, Volume 177, October 2025, article number 106333. The work was partly supported by the Cambridge Trust’s Vice-Chancellor’s Award. Coppola reported no conflicts of interest. The research was conducted at the University of Cambridge and the Lincolnshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust.