(Photo by Alexander Shenkin on Unsplash)

(Photo by Alexander Shenkin on Unsplash)

Social change organizations in the United States have been accustomed to developing strategies in fairly resilient systems with relatively predictable patterns and behaviors. But the rapid speed, scale, and lack of restraint of recent Trump administration decisions have forced us to question the assumptions our strategies are built on and explore new models for understanding what impact might be possible in a moment that requires emergent approaches to strategy development.

Last summer, coauthors Tom Glaisyer and Liz Ruedy wrote about different types of chaos factors: events which, if they were to occur, would introduce significant volatility into the system. This included so-called “Dragon Kings,” a term coined by Didier Sornette to describe events that, while predictable, unexpectedly lead to system collapse because we under-appreciate the scale of the event or how interdependent aspects of the system are. We believe that the volatility of this moment, combined with the potential intersection of other chaos factors and polycrises, create the conditions for this type of collapse scenario. But because a collapsing system may mimic one that is in decline right up until the moment of collapse, the social change community may be lured into protecting a system that is no longer viable or freezing in place entirely.

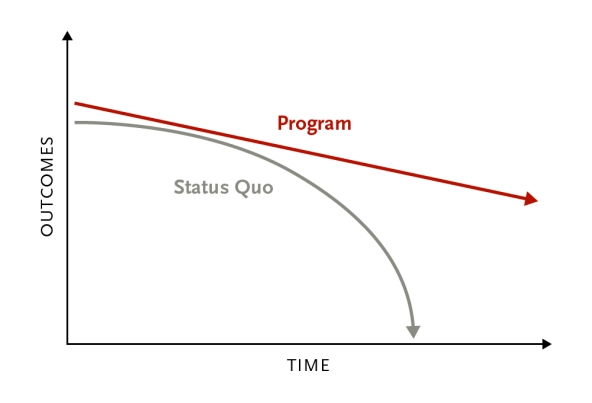

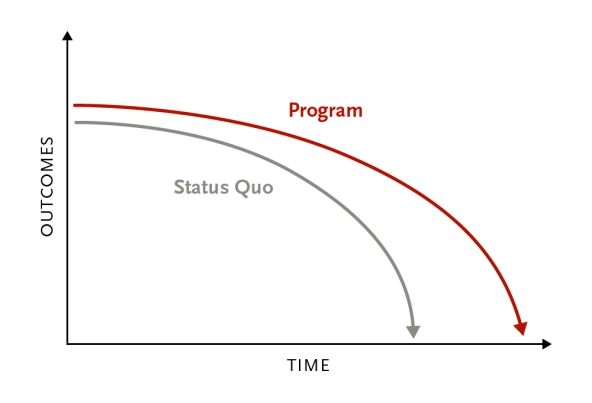

This prompted us to reflect on an idea that we previously workshopped together, which eventually became six models for understanding impact. The hypothesis behind these impact models is that impact must be understood against the “status quo” system of a trajectory: What would have happened absent the intervention? But these impact models did not consider that the status quo trajectory might be one of rapid, massive collapse. We propose that there are four additional impact models to consider that can help test assumptions, drive contingency plans, and move quickly from uncertainty to action. Most importantly, we hope these models will spur the social change community to think beyond the status quo and commit now to the work of repair and reimagination. Only by doing this can we help lay new groundwork for political, social, and economic systems that are just and equitable.

Achieving Impact in Collapsing Systems

Much has been written about how deeply concerning it should be for the pro-democracy movement to witness the administration’s actions over the last few months. We will not restate the details here, but we do want to emphasize that the breadth and consequences of these changes go well beyond policy differences. They throw into question the separation of powers, the rule of law, civil rights, and the role of the federal government in society. This strategy, which has been described as a “shock and awe” approach, comes with incredible risk to our governing institutions.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

No one can know for sure how the massive ripple effects of these actions will intersect with other potential Dragon King events, including global economic and trade instability, wealth inequality, technological change, climate-related disruptions, the emergence of new pathogens, the dissolution of the post-WWII international security apparatus, and more. What does seem clear, however, is that the administration is willing to accept this risk as a means toward a larger end: a fundamental remaking of American society.

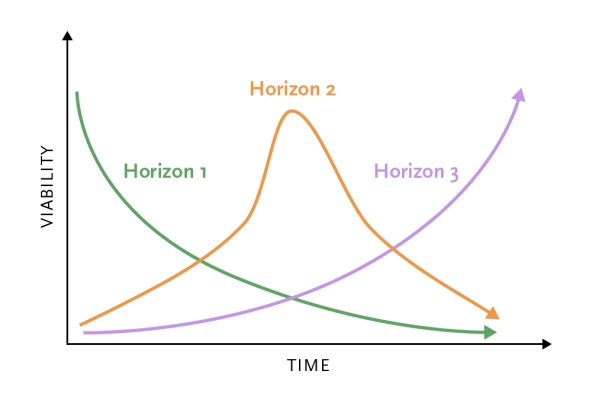

The three horizons framework (originally developed by McKinsey and Company but since reimagined by Bill Sharpe and others in the futures and foresight community) provides a helpful way to understand this dynamic. The collapsing system is, essentially, horizon one, its descent into non-viability steepening dramatically after a Dragon King event. Horizon two represents an intermediary period marked by chaos and uncertainty, but also experimentation and the stress-testing of nascent norms and institutions. Horizon three is the system that eventually emerges, perhaps reflecting some aspects of horizon one and two but ultimately different in its attributes, behavior, and outcomes.

For the social sector to achieve meaningful impact in a collapse scenario, it must acknowledge that preservation of the current system as-is cannot be its goal. Continuing to pursue a “return to normal” will only prolong the harms associated with a system in rapid decline and cede the creation of new systems to others. In other words, the social sector must consider not only the trajectory of the status quo system—which in our models is represented by a sudden, massive downward curve—but what emerges in its wake.

We propose four additional models to help the social sector understand what impact might look like in collapsing systems, noting that perhaps the most important thing is that no impact in this type of system will be sustainable absent a clear vision for the future that organizations are working toward. These impact models therefore consider not just outcomes that address urgent threats, but whether and how those outcomes can build (or blunt) momentum in horizon two and eventually influence the emergence of horizon three. We don’t see a hierarchy within these models but rather see them as alternatives that can be linked. To be successful in the collapse scenario, actors must see connections between models and make fast pivots as the context shifts and the relevance of different impact models change.

Protective

In a collapsing system, harms will be felt earliest, and most significantly, by communities that have long been targeted or marginalized within that system. As basic protections and fail-safes fall away, they will be subject to even greater attacks. The protective model is not focused on preserving the status quo by propping up ineffective norms and institutions. Instead, it builds and leverages power to counteract the worst harms, strengthen community resilience, and preserve values of care and belonging to carry people through crisis.

One example of approaches that fall under this model is mutual aid groups. According to writer and activist Dean Spade and the Big Door Parade, mutual aid projects are a form of political participation in which people take responsibility for caring for one another and changing political conditions. Mutual aid grew in prominence during the early days of the pandemic, perhaps the closest recent analogue that we have of a collapsing system, but communities in the United States have engaged in mutual aid for generations as a way to contend with malign or failing aspects of our political, economic, and social systems.

Protective impact is achievable only through deep and trusted relationships with communities and a willingness to invest in well-being and resilience of frontline actors. It requires a high level of comfort with experimentation and adaptation and familiarity with emergent strategy. Put bluntly, those seeking to achieve protective impact must be prepared to cede power and decision-making to community members and leaders who understand needs and context and can most accurately assess the potential risks and benefits of different tactics.

Blocking

Collapsing systems can be precipitated or accelerated by deliberate efforts to weaken them and sow chaos, often to exert control over the system that emerges in its place. If a collapsing system seems likely to give way to an even more dysfunctional or inequitable alternative, then the blocking impact model may be an appropriate response. This model can slow down both the pace of collapse and the emergence of worse alternatives.

Tactics that support a blocking impact model are extremely varied, from preserving public access to research studies to providing know-your-rights training, or refusing to comply with orders that are not required by, or may violate, the law. Maria Stephan, an expert in nonviolent civic action, has described this kind of work as “collective stubbornness.”

This impact model can come at great cost to those involved—particularly those who are already vulnerable within the system because of their identity or positionality—and so organizations working toward this model should acknowledge a duty of care and provide adequate legal, financial, and mental and physical health and safety resources to the fullest extent possible to those engaging in the work. Organizations should have a clear understanding of the risks and a plan to mitigate them should they occur. They will also want to have a well-considered strategy for whether and how to publicize their work. Organizations should ask themselves: Does a highly public campaign of non-compliance rally others to the cause, or does it create unnecessary targets?

Disruptive

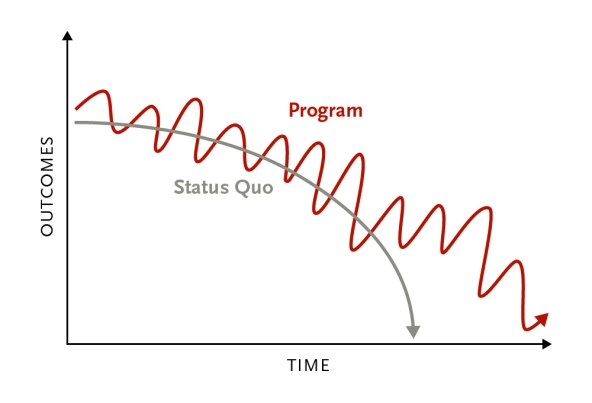

This model explicitly rejects the trap of trying to maintain the status quo and achieves impact by embracing the fact that as the legacy system deteriorates it is possible to shed the constraints, rules, and norms that do not serve the social sector. It leans into the chaos in the hopes of addressing immediate threats or openings, requiring us to question assumptions about what’s allowed and what will gain traction. The trajectory of a disruptive model is highly uncertain. It can yield significant impact in the short term, but in the longer term it will most likely only slow down the pace of collapse.

Political satire, boycotts, and strikes are all examples of the disruptive model, because they subvert unspoken rules of political and economic power. Global health activist and Yale professor Gregg Gonsalves referenced the disruptive strategies of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) movement as a model for how to approach our current moment, writing that after this work began, “our community broke through. We couldn’t be ignored any longer.”

Tactics deployed in support of a disruptive model can challenge widely and deeply held beliefs and can trigger powerful reactions and counter-reactions. It is also often left to actors who are most disenfranchised by the system to engage in this kind of work, perhaps because of an overarching assumption that they have the least to lose. But this can lead to further marginalization and misses a critical opportunity to build solidarity and interdependence. For these disruptive efforts to work, organizations need to be willing to take substantial risk in solidarity with frontline actors. As a result, like the blocking model, the disruptive model requires a clear understanding of risks and red lines, and effective legal, financial, and safety plans.

Leaders engaging with this model will also benefit from a strong public presence and ability to mobilize actors in support of a larger goal. In this highly polarized moment, actions that can draw a broad cross-section of supporters are less likely to be dismissed. Leaders also need to recognize that these strategies are highly emergent and will need to balance between a desire to pressure-test and build consensus around tactics before deploying them, and the necessity of quick action and rapid feedback loops to act, learn, and adapt quickly.

Creative

As one system collapses, there is an opportunity to shape what comes after. Certainly, the current administration has a strong perspective on what this new world order will look like. But with the intersection of multiple chaos factors, that future is anything but certain. With the system awash in uncertainty, there is an opportunity—even a responsibility— to pursue truly transformative impact. This means exploring the larger context in which the system sits. What relationships and emerging centers of gravity can be identified? What ideas or projects can be tested or nurtured? Which leaders have been marginalized by existing systems, but who are uniquely positioned to step up in this moment?

This could include envisioning new approaches to participatory governance, grounded in a fundamental reimagining of the systems they support. Or exploring core American concepts like freedom in a way that acknowledges our basic human need for connection and belonging. In our current moment, this almost certainly means thinking about our political and governing systems in terms that rebuild trust and community, connect to a sense of agency and participation that goes beyond elections, and centers individual and collective well-being, including health and economic security.

As with investments in innovation generally, organizations taking this approach must have deep comfort with experimentation and failure, an ability to incubate new ideas, and a willingness to be flexible on what “success” looks like—including accepting that they are likely going to fund models that may replicate and be repeated but will rarely scale magically. Organizations that are effective with this impact model will have skills in building power and coalitions, connections with leaders from many sectors, and a willingness to invest in the well-being and resilience of frontline actors. Notably, this work involves shifting the narrative that underpins it as much as the activities and tactics that drive it forward. So, organizations pursuing a creative impact model need to be able to tell stories about the futures they are working toward in a way that inspires and connects with people.

Conclusion

We know many of our peers, grantees, and partners have been working in authoritarian or destabilized contexts in the United States and around the world for a long time and want to be explicit that these models represent the perspective of systems thinkers who support the development of strategies for complex environments. We offer them in the spirit of framing insights drawn from those with hard-won experience, and we are eager to hear how these models for impact resonate with frontline changemakers.

As members of the pro-democracy and social change community who believe deeply in the cause of building more just, equitable societies, we wanted to close with two final thoughts:

First, we call on social change organizations to be open to discussing the possibility of a collapse scenario without worrying that it comes off as overly alarmist. If we agree that this scenario is at least somewhat possible, then we should consider what the effects might be, and how those effects would be disproportionately borne by people based on race, gender, immigration status, and class, and how we can be prepared to respond. Similarly, we need to acknowledge the fear and despair that this scenario might trigger but also find ways to nurture creativity and hope alongside those emotions. For funders, this means resourcing work that is focused on protection and healing as well as supporting generative spaces to explore different ways of acting and being.

Second, we need to engage in deep and humble listening about what comes next: What can we let go of, what do we want to carry with us, and what do we want to build? So much of the pro-democracy project specifically, and social sector investment more generally, has been to prop up broken systems, seeking to reform them and mitigate their harms, but not engaging nearly enough with thinkers and activists who have laid out fundamentally different visions for what truly inclusive, just, and equitable political, economic, and social systems could be. This moment requires us to engage in repair and reimagination—work that will include moving beyond the usual tools and frameworks to develop strategies and understand impact. As the futurist and writer Mia Birdsong has written, “it’s time to ditch the familiarity of the unfree, crumbling world. It’s time to stop mistaking false certainty for safety. We have to find the courage to stand in the long arc and do our part in the generational project of building the world worthy of our descendants.”

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Liz Ruedy, Tom Glaisyer & Rachel Reichenbach.