[this post was updated on October 18 to reflect new information and a refutal of the claim by the Chinese Government. It was again updated on October 21 to reflect new information, including claims that it concerned *two* tests, on July 27 and August 13]

If you want to have nightmares for days, then listen to Jeffrey Lewis menacingly whispering "fòòòòòòòòòòbs..." in the first few seconds of this October 7 episode of the Arms Control Wonk Podcast...

I bet some people connected to US Missile Defense hear this whisper in their sleep currently, given news that broke yesterday about an alledged Chinese FOBS test in August.

FOBS (Fractional Orbital Bombardment System) has menacingly been lurking in the background for a while. In the earlier mentioned podcast it was brought up in the context of discussing new pictures from North Korea showing various missile systems: including a new one which looks like a hypersonic glide vehicle on top of an ICBM (which is not FOBS, but FOBS was brought up later in the podcasts as another potential future exotic goal for the North Korean missile test program).

|

image: Rodong Sinmun/KCNA

|

But the days of FOBS being something exclusively lurking as a menace in the overstressed minds of Arms Control Wonks like Jeffrey are over: the whole of Missile Twitter is currently abuzz about it.

The reason? Yesterday (16 Oct 2021) the Financial Times dropped a bombshell in an article, based on undisclosed intelligence sources, that claims China did a test in August with a system that, given the description, seems to combine FOBS with a hypersonic glide vehicle. [edit: but see update at end of this post]

That last element is still odd to me, and to be honest I wonder whether things have gotten mixed up here: e.g., a mix-up with a reported Chinese suborbital test flight of an experimental space plane from Jiuquan on 16 July this year. [edit: and this might be right, see update at the end of this post]

Anyhow: the FT claims that China:

"tested a nuclear-capable hypersonic missile in August that circled the globe before speeding towards its target".

"Circled the globe" before reaching it's target: that is FOBS.

FOBS

So, for those still in the dark: what is FOBS?

FOBS stands for Fractional Orbital Bombardment System. Unlike an ICBM, which is launched on a ballistic trajectory on the principle of "what goes up must come down", FOBS actually brings a nuclear payload in orbit around the earth, like a satellite.

For example, a very Low Earth Orbit at an orbital altitude of 150 km, which is enough to last a few revolutions around the earth. At some point in this orbit, a retrorocket is fired that causes the warhead to deorbit, and hit a target on earth.

FOBS was developed as an alternative to ICBM's by the Soviet Union in the late 1960-ies, as a ways to evade the growing US Early Warning radar system over the Arctic. Soviet ICBM's would be fired over the Arctic and picked up by these radar systems (triggering countermeasures even before the warheads hit target). But FOBS allowed the Soviet Union to evade this by attacking from unforseen directions: for example by a trajectory over the Antarctic, which would mean approaching the US from the south, totally evading the Early Warning radars deployed in the Arctic region.

In addition, because FOBS flies a low orbital trajectory (say at 150 km altitude), whereas ICBM's fly a ballistic trajectory with a much higher apogee (typically 1200 km), even when a conventional trajectory over the North Pole would be used, the US radars would pick up the FOBS relatively late, drastically lowering warning times (the actual flight times of an ICBM and a FOBS over a northern Arctic trajectory are not much different: ~30 minutes. Over the Antarctic takes FOBS over an hour. But of relevance here is when the missiles would be picked up by US warning radars).

The Soviet Union fielded operational FOBS during the 1970-ies, but eventually abandoned them because new western Early Warning systems made them obsolete. This notably concerned the construction of an Early Warning system in space, consisting of satellites that continuously scan the globe for the heat signatures of missile launches. DSP (Defense Support Program) was the first of such systems: the current incarnation is a follow-up system called SBIRS (Space-Based Infra-Red System). This eliminated the surprise attack angle of FOBS, because their launches would instantly be detected..

Reenter FOBS

But now China has revived the idea, moreover with an alledged test of an actual new FOBS system (while Russia also has indicated they are looking into FOBS again). From the description in the Financial Times, which is based on undisclosed intelligence sources, the Chinese FOBS system moreover includes a hypersonic gliding phase. [edit: but see update at the end of this post]

Initially this surprised me: I was of the opinion (and quarrelled with Jeffrey Lewis about this, but am man enough to now admit I was wrong and he was right. Sorry Jeffrey, I bow in deep reverance...) that FOBS in 2021 had very little over regular ICBM technology and was therefore a very unlikely strategy, feasible only as a desperate last defensive act of revenge before total annihilation in case of an attack by others. Because using FOBS in an offensive tactical role would guarantee you to lead to Mutually Assured Destruction.

I still stand behind that last part, but clearly, China thinks they nevertheless need FOBS. Why?

FOBS still has one advantage over regular ICBM's. That is, that a southern trajectory over Antarctica approaching the US mainland from the south, while not going undetected by SBIRS, still avoids warhead intercepts by the US anti-Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) systems, that are currently geared to intercept a regular ICBM-attack over the Arctic or from the west (North Korea).

I should ad here: "for the time being".... The logical answer by the US (unless they chose to continue to ignore China with regard to BMD, as they did untill now) will now be to extend their BMD coverage to the south. For countering FOBS, they could use the same AEGIS SM-3 technology that they used to down the USA 193 satellite in 2008 (Operation Burnt Frost).

Here are two maps I made, one for a FOBS attack on Washington DC from China and one for a FOBS attack on Washington DC from North Korea. The red lines are ballistic ICBM trajectories (over the Arctic), and current BMD sites are meant to intercept these kind of trajectories. The yellow lines are FOBS trajectories over the Antarctic, showing how these attack the USA "in the back" of their missile defenses by coming from the south instead.

|

hypothetical FOBS attach from China. Click maps to enlarge

|

|

hypothetical FOBS attack from North Korea. Click map to enlarge

|

As the USA is currently putting much effort in Ballistic Missile

Defense, developing a new FOBS capacity could be a way by which China is warning

the USA that even with BMD, they are still vulnerable: i.e. that they

shouldn't attempt a nuclear attack on China from a notion that their

BMD systems make them invulnerable to a Chinese answer to such an

attack.

FOBS is hence a way of creating and utilizing weaknesses in the current BMD capacity of the USA, as a counter capacity.

It should be remarked here that the US BMD capacity is geared towards

missiles fired by Russia or by 'Rogue Nations' like North Korea and Iran.

The USA seems to have largely ignored China so far

with regard to BMD. Meanwhile, China is concerned with the US

BMD development, particularly deployment of BMD elements in their

immediate region.

So this FOBS experiment could also be a way

in which China tries to force the US to finally take the Chinese

concerns about US BMD deployments and the inclusion of their region into

such deployments, serious.

Outer Space Treaty

China (like the US and Russia) is a signatory of the Outer Space Treaty (or, in full: the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies).

FOBS seems to be a violation of this treaty, as Article IV of the treaty clearly states that:

"States Parties to the Treaty undertake not to place in orbit around the earth any objects carrying nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction"

This is exactly what FOBS does: it (temporarily) places a nuclear weapon in orbit around earth, so that they can later bring it down over a target.

The Soviet Union, when testing FOBS in the late '60-ies, tried to get out from under this by claiming that, as their FOBS did not complete a full orbit around the Earth, article IV of the treaty didn't apply. The US Government, surprisingly -and for opportunistic reasons- went along with this interpretation (see this article in The Space Review). Which is, pardon me the word, of course bullshit: in the sense of orbital mechanics (that is to say; physics), FOBS clearly does place an object in orbit, and it is very clear too by the fact that after launch it needs an actual, separate deorbit burn to get it down on the target.

North Korea and FOBS

How about North Korea? As I mentioned, FOBS has been repeatedly mentioned as a potential route North Korea might take with its nuclear missile program. Some fear that NK could be developing a FOBS capacity in order to have a means of final-revenge-from-over-the-grave from the Kim Jong Un regime in case of a 'decapitation' attempt (an attempt to end the Kim Jong Un regime by a targetted military strike on KJU and his family members).

One reason behind this fear is that North Korean Kwangmyŏngsŏng (KMS) satellite launches were on a trajectory over Antarctica, bringing the payload over the US only half a revolution after the launch.

Compare this launch trajectory of KMS 3-2 in December 2012 for example (which comes from this 2012 blog post), to the hypothetical FOBS trajectory in the map below it: the similarities are obvious (if perhaps superficial).

|

KMS satellite launch trajectory (above) and hypothetical FOBS attack from North Korea (below). Click map to enlarge

|

It wouldn't surprise me if FOBS will quickly replace the EMP 'threath' that over the past decade has been hyped by certain hawkish circles in the US defense world, as the horror-scenario-en-vogue.

Something worse than FOBS? DSBS!

So, can we think of something even more sinister than FOBS? Yes, yes we can, even though so far it is completely fictional and a bit out there (pun intended).

Let us call this very hypothetical menace DSBS. It is truely something out of your nightmares.

DSBS is a name I coined myself for a so far nameless concept: it stands for Deep Space Bombardment System. DSBS at this point is purely fictional, with no evidence that any nation is actively working on it: but the concept nevertheless popped up, as a distant worry, in a recent small international meeting of which I was part (as the meeting was under Chatham House rules, I am not allowed to name participants). So I am not entirely making this up myself (I only made up the name to go with this so far unnamed concept).

The idea of DSBS is that you park and hide a nuclear payload in Deep Space, well beyond the Earth-Moon system: for example in one of the Earth's Lagrange points. There you let it lurk, unseen (because it is too far away for detection). When Geopolitical shit hits the fan, all is lost and the moment is there, you let your DSBS payload return to earth, and impact on its target.

With the current lack of any military Xspace (Deep Space) survey capacity, such an attack could go largely undetected untill very shortly before impact. Your best hope would be that some Near Earth Asteroid survey picks it up, but even then, warning times will be short. Moreover, with the kind of impact velocities involved (12+ km/s), no existing Ballistic Missile Defense system likely is a match for these objects.

Far-fetched? Yes. But that is also something once said about FOBS...

(Note: I hereby claim all movie rights incorporating DSBS scenario's)

(added note: I only now realized, when answering a comment to this blogpost below, that, unlike FOBS or placing something in GEO, a DSBS parked in one of the Lagrange points would NOT violate Article IV of the Outer Space Treaty, because the device would NOT be in orbit around Earth (but co-orbital with Earth).

UPDATE 18 Oct 2021 10:45 UT and 20:10 UT:

NOT FOBS?

China denies that they did a FOBS test: "this was a routine test of a space vehicle to verify technology of spacecraft's reusability", says a Chinese government spokesman. They reportedly also say the test happened in July, not August. That could mean that this earlier reported test flight of a prototype space plane on July 16 was concerned (a suspicion I already voiced earlier in this blogpost and at the Seesat-L list).

Of course, as Jeffrey Lewis rightfully remarks, spaceplane technology shares a lot with FOBS technology. In Jeffrey's words: "China just used a rocket to put a space plane in orbit and the space plane glided back to earth. Orbital bombardment is the same concept, except you put a nuclear weapon on the glider and don’t bother with a landing gear."

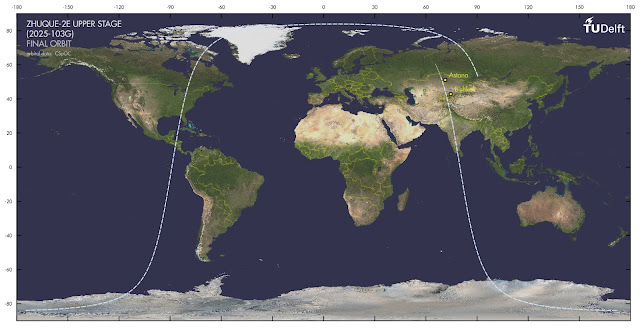

At the time, this space plane test was interpreted to have been suborbital, as the space plane reportedly landed in Alxa League, 800 km Badanjilin Airport, 220 km from the launch site, Jiuquan. I today however realised that this might have been a misinterpretation: it might actually have been an orbital, not suborbital, test fligth landing at the end of the first revolution.

Indeed, I managed to create a hypothetical 41.2 degree inclined proxy orbit for a launch from Jiuquan that brings it over Alxa League Badajilin Airport at the end of the first revolution.

Slightly more on this in this follow-up blogpost. which also points out that a Chinese source confusingly points to yet another airport as the landing site of the July 16 space plane test (if it was a space plane at all and not some upper atmospheric aircraft vehicle).

It could be that the Chinese Government is now seizing on the July 16 test to explain away a later FOBS test.

|

click map to enlarge

|

UPDATE 21 October 2021 10:25 UT:

New information circulated by Demetri Sevastopulo, the FT journalist that broke the story, indicates that there were *two* tests, on July 27 and August 13. The first date tallies with rumours that reached me on July 29 about an 'unusual' Chinese test apparently having taken place (that I at the time erroneously though might refer to the July 16 'space plane' test).