In the early morning of 26 November 2014 between 03:35 and 03:40 UT, a very slow, long duration fireball was observed from the Netherlands, Germany and Hungary (see

earlier post).

The fireball was quickly suspected to be caused by the fiery demise of a Soyuz third stage, used to launch ISS expedition crew 42, including ESA astronaut

Samantha Cristoforetti, to the International Space Station on November 23.

|

| Video still image from Erlangen, Germany (courtesy Stefan Schick) |

Analysis

In this blog post, which is a follow-up on an

earlier post, I will present some results from my analysis of the re-entry images, including a trajectory map, speed reconstructions and an altitude profile. The purpose of the analysis was:

1) to document that this indeed was the re-entry of 2014-074B;

2) to reconstruct the approximate re-entry trajectory;

3) to reconstruct the approximate altitude profile during the re-entry.

Data used

Three datasets were available to me for this analysis:

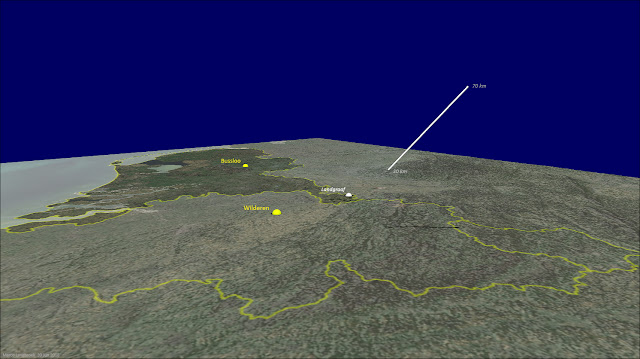

1) imagery from three photographic all-sky meteor cameras in the Netherlands, situated at Oostkapelle, Bussloo and Ermelo (courtesy of Klaas Jobse, Jaap van 't Leven and Koen Miskotte);

2) data from two meteor video camera stations (HUBAJ and HUBEC) situated in Hungary (courtesy of Zsolt Perkó and Szilárd Csizmadia);

3) imagery from a wide angle fireball video camera situated at Erlangen, Germany (courtesy Stefan Schick).

Some example imagery is below:

|

| Detail of one of the Bussloo Public Observatory (Netherlands) all-sky images, courtesy Jaap van 't Leven |

|

| Detail of the Cyclops Oostkapelle (Netherlands) all-sky image, courtesy Klaas Jobse |

|

| Detail of the Ermelo (Netherlands) all-sky image, courtesy Koen Miskotte |

|

| Stack of video frames from Erlangen (Germany), courtesy Stefan Schick |

|

| Stack of video frames from HUBEC station (Hungary), courtesy Szilárd Csizmadia and Szolt Perkó |

Astrometry

The Hungarian data had already been astrometrically processed with METREC by Szilárd Csizmadia and came as a set of RA/Declination data with time stamps. The Dutch and German images were astrometrically processed by myself from the original imagery.

The German Erlangen imagery was measured with AstroRecord (the same astrometric package I use for my satellite imagery). An integrated stack of the video frames resulted in just enough reference stars to measure points on the western half of the image. As it concerns an extreme wide field image with low pixel resolution and limited reference stars, the astrometric accuracy will be low.

AstroRecord could not be used on the Dutch All-Sky images because of the extreme distortion inherent to imagery with fish-eye lenses. They were therefore measured by creating a Cartesian X-Y grid over the image, centered on the image center (the zenith). Some 25 reference stars per image were measured in this X, Y system, as well as points on the fireball trail. From the known azimuth and elevation of the reference stars, the azimuth and elevation of points on the fireball trail were reduced. While obtaining the azimuth with this method is a straight forward function of the X, Y angle on the images, obtaining the elevation is more ambiguous. Based on the known positions of the reference stars and their radius (in image pixels) with respect to the image center, a polynomial fit was made to the data yielding a scaling equation that was used to convert the radius with respect to the image center of the measured points on the fireball trail to sky elevation values.

Unlike meteoric fireballs, rocket stage re-entries are long-duration phenomena. The German and Hungarian data, being video data, had a good time control. The Dutch all-sky camera data, being long duration photographic exposures, had less good time control, even though the start- and end-times of the images are known. The trails for Oostkapelle and Ermelo had no meaningful start and end to the trails. Bussloo does provide some time control as the camera ended one image and started a new one halfway the event: the end point of the trail on the first image corresponds to the end time of that image, and similarly the start on the next image corresponds to the start time of that image. There was 7 seconds in between the two images. Time control is important for the speed reconstructions, but also for the astrometry (notably the determination of

Right Ascension).

Data reduction and problems

The

Azimuth/Elevation data resulting from the astrometry on the Dutch data were converted to

RA/

DEC using formulae from Meeus (1991). For these Dutch data, the lack of time control is slightly problematic as the RA is time-dependent (the declination is not). There is hence an uncertainty in the Dutch data.

The data where then reduced by a method originally devised for meteor images: fitting planes through the camera's location and the observed sky directions, and then determining the (average) intersection line of that plane with planes fitted from the other stations, weighted according to plane intersection angle. This is the method described by

Ceplecha (1987). The plane construction was done in a geocentered Cartesian X-Y-Z grid and hence includes a spherical earth surface. The whole procedure was done using a still experimental Excel spreadsheet ("TRAJECT 2 beta") written by the author of this blog, coded serendipitously to reduce meteoric fireballs a few weeks before the re-entry.

I should warn that this method is actually not too well suited to reduce a satellite re-entry. The method is devised for meteoric fireballs, who's luminous atmospheric trajectory is not notably different from a straight line (fitting planes is well suited to reconstruct this line). A rocket stage re-entering from Low Earth Orbit however has a notably curved trajectory: as it is in orbit around the geocenter, it moves in an arc, not a straight line. This creates some problems, notably with the reconstructed altitudes, and increasingly so when the observed arc is longer. Altitudes reconstructed from the fitted intersection line of the planes come out too low, notably towards the middle of the used trajectory arc. The resulting altitude profile hence is distorted and produces a U-shape. The method is also problematic when stations used for the plane fitting procedure are geographically far removed from each other. In addition, the method is not very fit for long duration events.

The data were reduced as three sets:

1) data from the Dutch stations (independent from the other two datasets);

2) data from the German station combined with the two eastern-most Dutch stations;

3) data from the Hungarian stations (independent from the previous two datasets).

Dataset (2) combines data from stations geographically quite far apart. This is probably one of the reasons why this dataset produces a slightly skewed trajectory direction compared to the other two datasets.

The Dutch images have the event occurring very low in the sky (below 35 degrees elevation for Oostkapelle and below 25 degrees elevation for Bussloo and Ermelo). The convergence angles between the observed planes from the three stations is low (14 degrees or less). This combination of low convergence angles and low sky elevations, means that small measuring errors can have a notable scatter in distance as a result.

Results (1): trajectory

|

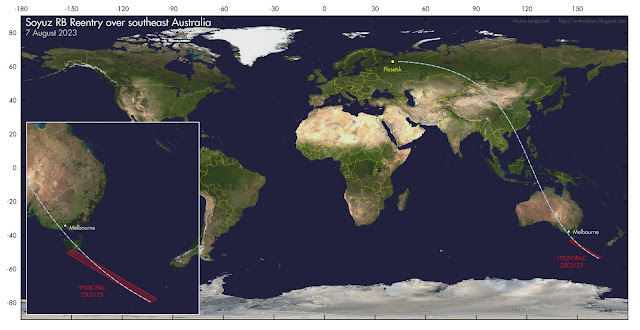

| reconstructed trajectory (red dashed line and yellow dots) |

The map above (in conic equal-area projection) shows the reconstructed trajectory as the yellow dots and the red dashed line. White dots are the observing stations.

The thin grey line just north of the reconstructed trajectory is the theoretical ground track resulting from a SatAna and SatEvo processed TLE orbital efemerid set for the rocket stage. This expected ground track need not perfectly coincide with the real trajectory, as the orbit changes rapidly during the final re-entry phase.

The reconstructed trajectory converges towards the theoretical (expected) ground track near the final re-entry location, above Hungary, but is slightly south of it earlier in time. The horizontal difference is about 30 km over southern England, 25-20 km over northern France due south of the Netherlands, 17-16 km over southern Germany and less than 3 km over Hungary.

This difference is most likely analytical error, introduced by the low sky elevations and convergence angles as seen from the Netherlands. On the other hand, the Hungarian observations (with stations on the other, southern side of the trajectory compared to the Dutch and German stations and reduced completely independent from the other data) place it slightly south too. So perhaps the deviation is real and due to orbital inclination changes during the final re-entry phase. Indeed, a SatEvo evolution of the last known orbit suggest a slight decrease in orbital inclination over time, although not of the observed magnitude.

The results from Erlangen come out slightly skewed in direction, likely for reasons already discussed above. The Hungarian results are probably the best quality results.

Results (2): altitudes and speed

|

| altitudes (in km) versus geographic longitude |

As mentioned earlier, the altitudes resulting from the fitted linear planes intersection line come out spurious due to the curvature of the trajectory. Altitudes were therefore calculated from the observed sky elevations and known horizontal distance to the trajectory. The horizontal distance "

d" between the observing station and each resulting point on the trajectory were calculated using the geodetic software

PCTrans (software by the Hydrographic Service of the Royal Dutch Navy). Next, for each point the (uncorrected) altitude "

z" was calculated from the formula:

z =

d * tan(

h),

where "

h" is the observed sky elevation in degrees.

This is the result for a "flat" earth. It has hence to be corrected for earth surface curvature, by adding a correction via the geodetic

equation:

Zc =

r - sqrt (

r 2 +

d 2) [all values in meters],

where "

r" is the Earth radius for this latitude, "

d" the horizontal distance between the observing station and the point on the trajectory, and "

Zc" the resulting correction on the altitude calculated earlier.

The results are shown in the diagram above, where the elevation has been plotted as a function of geographic longitude. It suggests an initial rapid decline in altitude from ~125 km to ~100 km between southern England and northern France, an altitude of ~100 km over southern Germany, and a very rapid decline near the end, with altitudes of 60-50 km over Lake Balaton in Hungary. Whether the curvature in the early part of the diagram is true or analytical error is difficult to say, although it is probably wise to assume it is analytical error.

Apart from the match in trajectory location, speed is another measure to determine whether this was the decay of 2014-074B or not. Meteors always have an initial speed larger than 11.8 km/s (but: for extremely long duration slow meteors deceleration can decrease the terminal speed considerably below 11.8 km/s later on in the trajectory). Objects re-entering from geocentric (Earth) orbit have speeds well below 11.8 km/s, usually between 7-8 km/s depending on the orbit apogee. When speed determinations come out well below 11.8 km/s, a re-entry is a likely although not 100% certain interpretation. When speed determinations come out at 11.8 km/s or faster, it is 100% certain a meteor and no re-entry.

By taking the distance between two points on the trajectory with a known time difference, I get the following approximate speeds:

- from the Hungarian data: 7.0 km/s;

- from the Dutch data: 9.0 km/s;

- from the German data: 9.4 km/s.

These are values that are obviously not too accurate, but nevertheless reasonably in line with what you expect for a re-entry of artificial material from geocentric (Earth) orbit.

It should be noted that if the southern deviation (see trajectory results above) of the trajectory data is analytical error, the speed of the Dutch and German observations is a slight overestimation, while the Hungarian results will be a slight underestimate. This would bring the speeds more in line with each other, and even closer to what you expect from a rocket stage re-entry from Low Earth Orbit.

Discussion and Conclusions

The trajectory and speed reconstructions resulting from this analysis strongly indicate that the fireball seen over northwest and central Europe on 26 November 2014, 03:35-03:40 UT indeed was the re-entry of the Soyuz third stage 2014-074B from the Soyuz TMA-15M launch. Although there are some slight deviations from the expected trajectory, the results are close enough to warrant this positive identification.

The deviations are easily explained by analytical error, given the used reduction method and the not always favourable configuration of the photographic and video stations with regard to the fireball trajectory. Notably, the large distance of the Dutch stations to the trajectory resulting in very low observed sky elevations and low plane fitting convergence angles for these stations is a factor to consider. Nevertheless, and on a positive note, the final result fits the expectations surprisingly well.

The data suggest that the object was at an altitude approaching 125 km (close to the expected final orbital altitude on the last completed orbit) while over southern England and the Channel, had come down to critical altitudes near 100 km while over southern Germany, and was coming down increasingly fast at altitudes of 60 km and below while over Hungary.

The Hungarian observations show that the rocket stage re-entry continued beyond longitude 19.3

o E and below 46.45

o N, and happened some time after 03:39:20 UT. It likely not survived much beyond longitude 21

o E.

The nominal re-entry position and time given in the final

JSpOC TIP message for 2014-074B are 03:39 +/- 1 min UT and latitude 47

o N longitude 17

o E, with the +/- of 1m in time corresponding to a +/- of several degrees in longitude. This is in reasonable agreement with the observations.

Acknowledgements

I thank Zsolt Perkó, Szilárd Csizmadia, Stefan Schick, Jaap van 't Leven, Klaas Jobse and Koen Miskotte for making their images and data available for analysis. Carl Johannink contributed some mathematical solutions to the construction of the spreadsheet used for this analysis.

Note: another Soyuz rocket stage re-entry from an earlier

Soyuz launch towards the ISS was observed from the Netherlands and

Germany in December 2011, see earlier post here. As to why it takes such a rocket stage three days to come down, read FAQ here.

Literature:

- Ceplecha Z., 1987: Geometric, dynamic, orbital and photometric data on meteoroids from photographic fireball networks. Bull. Astron. Inst. Czech. 38, p. 222-234.

- Meeus J. (1991): Astronomical Algorithms. Willmann-Bell Inc., USA.