|

| click map to enlarge |

|

| click map to enlarge |

The second SpaceX Starship Integrated Test Flight initially launched successfully on November 18. The spacecraft separated succesfully from the first stage (which however violently disintegrated almost immediately after this). However, at 148 km altitude just before engine shutdown and coasting phase commencement, something went wrong and the spacecraft's auto-destruction mechanism destroyed the spacecraft.

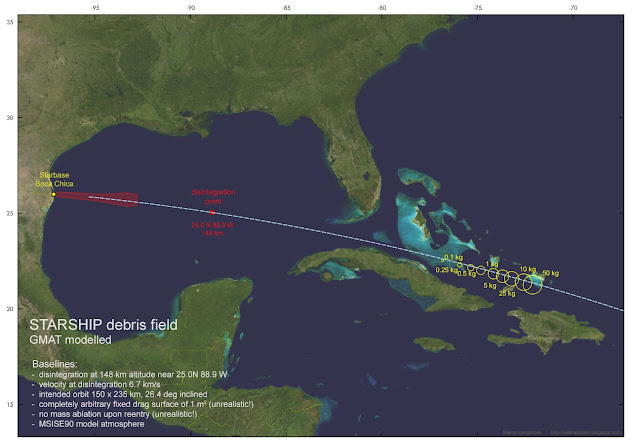

I estimate the point of destruction to be in the middle of the Gulf or Mexico, near 25.0 N 88.9 W, although it could perhaps be slightly more downrange than that, closer to Cuba and Florida.

The question then popped up: how far downrange from the destruction point would any remaining debris end up? The answer to that question strongly depends on amongst others the speed upon destruction, and the sizes and masses of any debris.

The map in top of this post gives an indication based on a somewhat simplistic modelling attempt, further discussed below.

After some initial educated guesses, I decided to investigate the issue further using a simple model in GMAT (the General Mission Analysis Tool). Live-feed data shown in the webcast from just before telemetry contact was lost indicated a speed of about 6.7 km/s, at 148 km altitude.

Using these base values and my estimated location for the point of destruction, I modelled the resulting vector in GMAT, using the MSISE90 model atmosphere that is part of GMAT. I modelled results for a number of masses, ranging from 0.1 kg to 50 kg, and with a fixed drag surface of 1 m2 for each fragment irrespective of mass. This is not very realistic by the way, but sufficient for a general idea nevertheless.

Another deviation from reality is that there was no further mass loss (e.g. because of ablation upon reentry) of the debris pieces in the model. So, this is a bit a case of a proverbial "spherical cow reentering" (but not in a vacuum: the MSISE90 model atmosphere was used to model atmospheric drag).

Nevertheless, this academic exercise does give a rough idea of where surviving debris might have ended up: likely some 1500 km downrange from the point of destruction, near the southeastern Bahamas, and north of Cuba and the Dominican Republic. see the map in top of this post, depicting the model results.

(I thank Ian Benecken, Scott Manley and Jonathan McDowell for initial discussions and suggestions on twitter. Any mistakes are solely mine)

UPDATES:

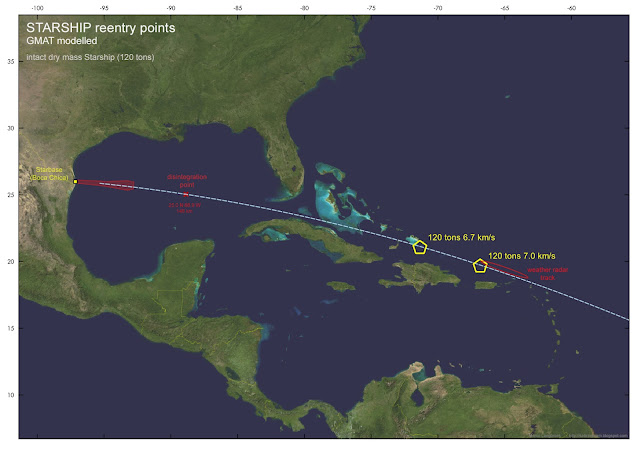

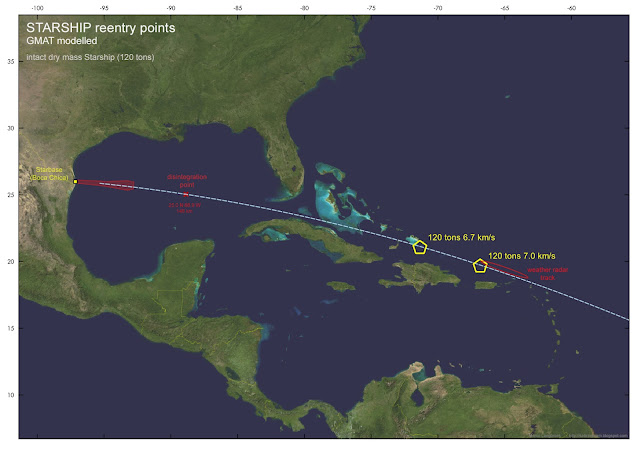

This NOAA weather radar image below by Kenneth Howard (source this tweet by Jonathan McDowell) shows a radar debris trail near Puerto Rico. There is also video footage from Puerto Rico of what looks to be a large Starship remnant reentering and breaking up, see this tweet. This is some 800 km further downrange than the model results, and probably caused by a sizable part of Starship (i.e. considerably larger and heavier than the debris pieces I modelled) disintegrating upon atmospheric reentry.

I modelled an intact Starship upper stage (120 tons dry mass, 63.6 m2drag surface) for two initial speeds at the "disintegration" point: 6.7 km./s and 7.0 km/s.

The latter value brings it close to where the weather radar depicts the debris trail. This could implicate it was largely intact untill it broke up in the upper atmosphere north of Puerto Rico:

|

| click map to enlarge |