UPDATED 29 May 2023 12:00 UTC to reflect alternative orbit option

UPDATED 30 May 7:45 UTC to add comparison with 2016 launch

UPDATE 30 May 22:00 UTC: the launch seems to have happened, around 21:30 UTC (May 30)

UPDATE 31 May: the launch reportedly failed early in flight due to a problem with the 2nd stage

(this post has been updated several times, with new pargraphs added, following development of the case. Newest paragraphs are near the bottom of the post)

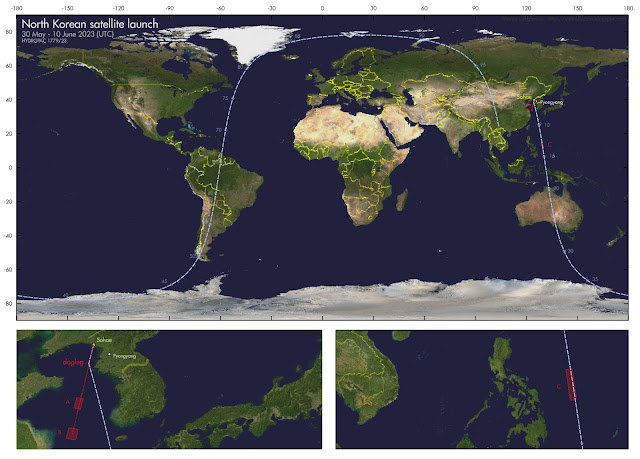

According to South Korean media, North Korea has informed Japan that they will launch a satellite between May 31 and June 11. Navigational Warnings have appeared that suggest a launch in this period as well.

Navigational Warning HYDROPAC 1779/23 (see below) gives three hazard zones, the first two of which line up with the Korean launch site Sohae. Below is the text of the Navigational Warning in question, and a map where I have plotted the three hazard zones A, B and C and the approximate launch trajectory I reconstruct from these (numbers next to the trajectory indicate minutes after launch):

[UPDATE: but see alternative option near bottom of post, that I am increasingly inclined to]

|

| click map to enlarge |

282008Z MAY 23

HYDROPAC 1779/23(91,92,94).

EAST CHINA SEA.

PHILIPPINE SEA.

YELLOW SEA.

DNC 11, DNC 23.

1. HAZARDOUS OPERATIONS, ROCKET LAUNCHING

301500Z MAY TO 101500Z JUN

IN AREAS BOUNDED BY:

A. 36-06.56N 123-33.07E, 35-24.31N 123-22.47E,

35-20.01N 123-48.37E, 36-02.26N 123-59.11E.

B. 34-05.54N 123-01.59E, 33-23.28N 122-51.53E,

33-16.32N 123-29.40E, 33-58.58N 123-40.04E.

C. 14-54.10N 128-40.06E, 11-19.18N 129-10.50E,

11-26.49N 129-54.08E, 15-01.42N 129-24.03E.

2. CANCEL THIS MSG 101600Z JUN 23.

Note that May 30, 15:00 UTC corresponds to May 31, 00:00 local date/time in North korea, and June 10, 15:00 UTC to June 11, 00:00 local date/time. So the window of the Navigational Warning, in local North Korean date/time, matches that given by North Korea.

|

| click map to enlarge |

Areas A and B between China and Korea are likely the splashdown zones for the first stage and fairings, area C east of the Philippines is the splash-down zone for the second stage. Their relative locations point to a dog-leg manoeuver just after launch, after first stage separation and fairing ejection. First stage and fairing continue on the original launch course untill splashdown, the second and third stage, after the dogleg, insert the payload into a ~78 degree (give or take a degree or two) inclined orbit.

The orbit is NOT sun-synchronous. It is different in orbital inclination than the orbits of the previous North Korean satellite launches: KMS (Kwangmyŏngsŏng) 3-2 and KMS 4, which are in 97.2-97.3 degree inclined orbits.

UPDATE (29 May 2023 12:00 UTC)

It was deep into the night when I originally wrote this blogpost. After a night's sleep and a discussion with Bob Christy, I am inclined towards another solution: direct insertion into a 97.2 degree inclined sun-synchronous orbit, followed by an avoidance manoeuvre of the 2nd stage after 3rd stage separation to avoid the 2nd stage falling on the Philippines:

|

| click map to enlarge |

|

| click map to enlarge |

The location of areas A and B would fit well with this scenario. The risky part is that it means an overflight of the coastal PRC and Taiwan early in the launch trajectory. If something goes awry, this could result in hardware coming down on the PRC, Taiwan of Philippines nevertheless.

Yet this option is more and more enticing to me. The resulting orbit would be sun-synchronous, i.e. fitting an optical reconnaissance satellite, and similar to the orbits of KMS 3-2 and KMS 4. The scenario to arrive there however differs from the 2012 and 2016 launches. Here initial launch direction is into the intended orbital plane and the 2nd stage is doing a post-separation avoidance manoeuvre; whereas in 2012 and 2016, the initial launch direction was different and the 3rd stage did a manoeuver and pushed the payloads into the final orbit. The post-separation avoidance manoeuver of the 2nd stage in the current scenario would point to a (new) re-startable 2nd stage, which is interesting

The 2nd stage will splash down into a very deep part (5.7 km) of the Pacific Ocean, which makes recovery very challenging. This could be another reason why they divert it into this direction. It could be an indication that the 2nd stage is something new that they don't want to fall into the wrong hands.

If the launch is done at similar solar elevations as in 2012 and 2016, we can expect launch near 21:50-21:55 UTC, about 1.5 hours after sunrise at Sohae.

The intended orbital altitude is probably near 500 km.

Below is a very rough orbit estimate for launch at 21:50 UTC on the first available date (May 31 6:00 local time in N Korea is May 30 in UTC):

KMS 5 for launch on 30 May 2023 21:50:00 UTC

1 70000U 23999A 23150.90972222 .00000000 00000-0 00000-0 0 06

2 70000 097.2299 155.8806 0003636 152.0900 325.4205 15.22766913 08

UPDATE (30 May 22:00 UTC):

Launch seems to have been near 21:30 UTC. here is an orbit estimate, assuming direct insertion into SSO, for launch at 21:30 UTC:

KMS 5 for launch on 30 May 2023 21:30:00 UTC

1 70001U 23999A 23150.89583333 .00000000 00000-0 00000-0 0 06

2 70001 097.2299 150.8669 0003636 152.0900 325.4205 15.22766913 01

UPDATE 30 May 2023, 7:45 UTC:

In the map below I have depicted the location of the hazard zones and (initial) launch directions for the launch of KMS-4 in 2016 (blue), and the upcoming launch (red). Note the difference in (initial) launch direction between 2016 and now, and the odd off-set chacater of area C for the current launch:

|

| click map to enlarge |

In 2016, it was the third stage that did a dog-leg to get the payload into a 97.2 deg inclined Sun-synchronous orbit. The initial launch trajectory was probably selected to minimize risk of the 1st stage falling on the PRC and the second stage falling on the Philippines:

|

| click map to enlarge |

It is very clear that the upocoming launch will be according to a different scenario than the 2016 KMS-4 launch. Something odd is happening with the second stage, clearly.

UPDATE 31 May 2023: LAUNCH FAILED TO REACH ORBIT

The launch failed in flight, according to the North Korean State News Agency KCNA due to a problem with the 2nd stage. The KCNA news report provides a launch time of 6:27 North Korean time (21:27 UTC May 30). It mentions that the launch was with a new type of carrier rocket, "Chollima-1", and gives the name of the failed satellite as "Malligyong-1".

It says that the failure was due to "losing thrust due to the abnormal starting of the second-stage engine after the separation of the first stage during the normal flight".

Yonhap reports the crash site as "200 km west" of the island of Eocheongdo. That matches well with area A, the first stage splash-down zone, from the Navigational Warnings (see map below). If the second stage failed to ignite, both the first stage and the second/third stage plus payload stack could have ended up here.

One of the stages has been recovered by South Korea, presumably from this area (photo's in this tweet thread). It seems quite intact and could be the spent first stage.

|

| click map to enlarge |

North Korea recently released images of the payload during factory testing, and already hinted at a nearby launch (see previous post here).

|

| image: KCNA |