|

image: KCNA/RodongSinmun

|

According to multiple western sources and North Korea, North Korea conducted a first full-power test-flight of its new Hwasong-17 ICBM on March 24, 2022, at 5:34 UT, from Sunan close to Pyongyang.

The Hwasong-17 is the Behemoth missile that was first revealed to the outside world one-and-a-half-years-ago during the 2020 October 10 parade in Pyongyang and surprised everyone by its massive size at the time. It is North-Korea's largest, heaviest missile so far and visually looks like a Hwasong-15 on steroids.

[NOTE: some sources are now casting some doubt on the missile identity, suggesting that footage from the failed March 16 launch (see below) was used. See comment at end of post]

The test launch was confirmed by North Korean State sources which produced a written account on their KCNA and Rodong Sinmun websites, accompanied by photographs, while KCNA also broadcast a video of the test. The imagery underlines how impressive the size of the Hwasong-17 is: it is a Monster of a missile!

|

image KCNA/Rodong Sinmun

|

|

| image KCNA/Rodong Sinmun |

|

| image KCNA/Rodong Sinmun |

The video report on the test as broadcast by the North Korean State Agency KCNA is spectacular, with a glamour role for the sunglasses-clad North Korean leader Kim Jung Un (look at 3:55 to 4:05 in the video below!). It evokes shades of a Hollywood action movie trailer.

(the actual footage of the test and test preparations starts at 3:25 in the video, after the usual bombastic introductions by news anchor Ri Chun-hee)

Earlier test flights of components of the same missile might have taken place in Februari and early March (but not on full power), according to western sources. North Korea claimed at the time that it was testing components for a reconnaisance satellite program.

We also know that on March 16, another test flight from the same launch-site (near Sunan Airport), possibly also a Hwasong-17, failed shortly after launch at an altitude of less than 20 km.

But the March 24 test flight appears to have been successfull, as claimed by both North Korea and western sources. According to North Korean official State sources it reached an apogee at a whopping 6248.5 km altitude, with a ground range of 1090 km and a flight time of long duration (1h 7m 30s).

Western sources that independently tracked the launch mention similar ballpark values for this test: apogee "6200 km" and range "1080 km" according to the S-Korea Joint Chiefs of Staff; apogee "6000 km" and range "1100 km" according to the Japanese Government. The missile came down in front of the Japanese coast inside Japan's EEZ, at some 180 km from Cape Tappi.

The apogee is at an extreme altitude, and this test was hence extremely lofted, as can be seen in this trajectory reconstruction I made:

|

click to enlarge

|

Looking into the necessary impulse in order to assess maximum range of the missile, I realized that the resulting nominal impulse of 7.85 km/s I reconstruct, actually means that the Hwasong-17 can achieve orbital speed. In other words: this means it is powerfull enough to, in principle, loft a payload to (low) earth orbit and get it (briefly) orbital!

Objects can complete at least one revolution around the earth if they have enough orbital velocity such that they can orbit at at least 100 km altitude (the exact value of the lower limit of orbital flight is debated: for circular orbits it might be possible at altitudes as low as 80-90 km, but it anyway strongly hinges on the drag characteristics of the object in question). The corresponding orbital speed at 100 km altitude is 7.84 km/s (for a circular orbit). The nominal impulse I get for the March 24 launch, at 7.85 km/s, matches that (in reality, it is more complex, as the missile will experience atmospheric drag during the initial phase of launch, which was not part of my reconstruction. And part of the initial impulse will be lost due to gravity pull before reaching 100 km altitude).

So in theory, this missile could briefly get an object (e.g. a warhead) in orbit around the earth, rather than on a suborbital ballistic trajectory. In case you wonder: it didn't on March 24, because it was not launched on an orbit insertion trajectory, but rather straight up.

|

image: KCNA/RodongSinmun

|

|

image: KCNA/Rodong Sinmun

|

|

image: KCNA/Rodong Sinmun

|

This was not something I had expected. But it gives a new meaning to North Korean claims from earlier this year that tests conducted then, possibly with Hwasong-17 components, where in connection to a space launch program.

They did fairly and squarely present the latest March 24 test as an ICBM test flight though.

The launch location at 39.188 N, 125.667 E (as geolocated from the imagery by Joseph Dempsey) was on a concrete strip about 1.75 km from the main buildings of Pyongyang Sunan airport. That concrete strip is part of the Si-Li Ballistic Missile Support Facility which itself is some 2.5 km southwest of the airport:

|

click map to enlarge

|

|

click map to enlarge

|

But let's get back to the realization that this missile can apparently reach orbital speeds. This means that it - or components of it - in theory can be used for road mobile satellite launches. But it can also mean that you can briefly bring a warhead in orbit, either for a full revolution or more, or - cough - for a "fractional" orbit....

Remember the discussion of the Chinese test of a FOBS ('Fractional Orbital Bombardment System') in July last year?! See this earlier post.

I have been doing some modelling. Based on specs of an early '60-era US warhead, the W56, I modelled whether a launch of a similar warhead into a very low 100 x 105 km, 98.0 degree inclined polar orbit from Sunan, could reach the USA.

I used the General Mission Analysis Tool for this, with the MISE90 model atmosphere and F10.7 solar flux set at 100. I modelled for a 275 kg warhead with assumed Cd 1.0 and a drag surface of ~0.15 m2 (comments on how realistic those values are, are welcome) and under the assumption that the launch vehicle does achive sufficient orbital speed to insert it in such a 100 x 105 km orbit. The modelled launch was in southern direction, taking the long but undefended southern Polar route over Antarctica, approaching the USA from the south after finishing just over half an orbital revolution. [info added later: The model is strictly for the warhead assuming release from the missile upon orbit insertion: I did not model prolonged coasting as part of a post-boost vehicle of any kind].

With the mentioned specifications, I model it to nominally come down fairly and squarely in Ohio (or any other place within the continental USA if you adjust the orbital plane launched into somewhat), as the map below in which I have plotted the modelled trajectory for the warhead shows....

|

click map to enlarge

|

So: is the development of this missile perhaps a prelude to the development of a North Korean FOBS? With a suitable warhead, it appears they could do it with this missile.

Incidentally: the flight-time of the March 24 test was similar to the on-orbit flight time needed to get from Sunan to the United States via the southern polar route. But that is likely coincidence.

Leaving FOBS aside for the moment: at any rate a missile with this power launched on a more conventional ballistic trajectory can easily reach any location within the continental United States, as well as Europe and the Pacific (but would need a working reentry vehicle of course, which is another matter). In addition to that, it means that North Korea now in theory also has a potential road-mobile reconnaisance satellite launcher in their arsenal.

|

image: KCNA/Rodong Sinmun

|

|

image: KCNA/Rodong Sinmun

|

|

image: KCNA/Rodong Sinmun

|

|

| image: KCNA/Rodong Sinmun |

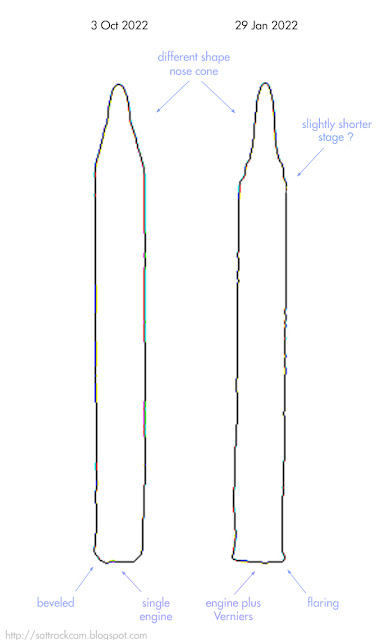

Added note: some sources are now casting some doubt on the missile identity, suggesting (with arguments from image analysis) that footage from the failed March 16 launch was perhaps presented by North Korea as being from the March 24 launch. The added suggestion is that the March 24 test missile might have been a Hwasong-15, not a Hwasong-17 as North Korea is claiming.

These objections are interesting, but multiple scenario's are possible. For example, they might have used footage from both test launches, certainly if iconic scripted propaganda scenes (e.g. KJU marching in front of the TEL leading his Rocket men) were shot during the preparations for the failed March 16 test. North Korea has been known to have doctored launch imagery for aesthetic/propaganda purposes before in the past, as I have shown for the historic first Hwasong-15 launch of 28 November 2017.

Whatever missile it really was: the missile performance shown by this test is remarkable and well beyond that of earlier North Korean ICBM launches. Western tracking of the missile test confirms the performance, so it is not just North Korean propaganda that can easily be waved away. This is a significant development, no matter how you look at it.