2025 State of the Rhino

Every September, the International Rhino Foundation (IRF) publishes our signature report, State of the Rhino, which documents current population estimates and trends, where available, as well as key challenges and conservation developments for the five surviving rhino species in Africa and Asia.

Key takeaways from the 2025 State of the Rhino report:

- Black rhinos have increased to 6,788 from the last count of 6,195 in 2022.

- The number of Indonesia’s Javan rhinos has dropped due to poaching.

- By the end of 2024, the number of white rhinos in Africa dropped to 15,752, down from 17,464 in 2023.

- Greater one-horned rhinos have been making use of improved habitats and wildlife corridors, and their numbers have increased to 4,075 from 4,014 in 2022.

- Median rhino populations in South Africa are well below numbers recommended by the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) African Rhino Specialist Group, meaning that many rhino populations are too small to be considered reproductively and genetically viable.

- A new tracking tool could help monitor rhinos whose horns were trimmed to deter poaching.

Download the 2025 State of the Rhino report

Rhino News to Watch

- The 20th Conference of the Parties (CoP) of signatories to CITES, the global wildlife trade agreement, takes place late in 2025 and provides an opportunity to review global rhino conservation efforts. During the CoP, the International Rhino Foundation (IRF) and Save the Rhino International will facilitate a panel discussion with rhino conservation, wildlife trade and law enforcement experts, as well as representatives from rhino range states and CITES Parties affected by the illegal rhino horn trade.

- The 2025 World Conservation Congress will include a motion to focus attention and resources on securing the remaining populations of Critically Endangered Sumatran and Javan rhinos in Indonesia.

- Highly trained dogs have found scat that is likely from Critically Endangered wild Sumatran rhinos in Indonesia’s Way Kambas National Park – the first such evidence found in years. Results from DNA testing are expected soon.

This report is dedicated to the committed individuals in African and Asian rhino range countries working to secure the five species of rhinos in the wild. The International Rhino Foundation especially respects and admires the tremendous sacrifices made by frontline rangers in rhino range countries. We are proud to support these efforts.

State of the Rhino

The International Rhino Foundation (IRF) is pleased to publish the newest version of our State of the Rhino report, IRF’s signature annual report detailing the status of rhino species.

As the only organization dedicated to protecting all rhino species around the world, we use this report to document current population estimates, highlight challenges facing conservation of the five remaining rhino species in Africa and Asia and make specific recommendations for the conservation of all rhino species.

This is the first year since 2022 that the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Species Survival Commission’s Asian and African Rhino Specialist Groups, along with TRAFFIC, have released new estimates of the global rhino population. The IUCN/TRAFFIC report authors rely on governments where rhinos live for information on populations and trafficking seizures.

The newest global rhino population estimates show the number of Indonesia’s Javan rhinos has dropped due to poaching, while black rhino numbers in Africa have increased, which is a win for this critically imperiled species.

The total global population of rhinos is approximately 26,700. White rhinos declined to 15,752 by the end of 2024, down from 15,942 at the end of 2021, a drop of about 190, though the numbers fluctuated significantly between 2021 and 2024. Javan rhinos declined from an estimated 76 to approximately 50, due entirely to heavy poaching losses. The Sumatran rhino population remained the same at an estimated 34-47, while greater one-horned rhino numbers rose from 4,014 to 4,075. Black rhinos increased to 6,788 from the last count of 6,195. These numbers do not include rhinos in zoos.

The Sumatran rhino population remained essentially the same since the 2022 estimates were issued and is considered to be seriously imperiled. A beacon of hope for this Critically Endangered species is the breeding program at the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary, a protected, semi-wild facility in Way Kambas National Park. The sanctuary has produced five rhino calves and continues its breeding efforts to create an insurance population of rhinos. All the rhinos at the sanctuary are doing well. Also, in the far northern corner of Sumatra, the Leuser ecosystem’s population of wild rhinos is still believed to be sound.

In more recent news, a team of dogs trained to detect Sumatran rhino scat found what is likely scat from Critically Endangered wild Sumatran rhinos in Indonesia’s Way Kambas National Park – evidence conservationists have tried for years to find. Authorities are awaiting DNA test results to confirm the scat is from Sumatran rhinos. The Government of Indonesia’s Ministry of Forestry has been integral to efforts to preserve Sumatran and Javan rhinos.

Greater one-horned rhino numbers increased marginally and are considered to be recovering. White rhino numbers are increasing in all range states except South Africa, where poaching caused a slight decline in population.

One issue of potential concern IRF identified in the report is that South Africa, the country with most of the world’s rhinos, has small median rhino population sizes – seven for white rhinos and 11 for black rhinos. These population sizes are well below the levels required to avoid inbreeding and loss of long-term evolutionary potential.

The IUCN/TRAFFIC report also outlines trends in trade and trafficking of rhino horn. It notes an emerging illegal rhino horn trade link between Mongolia and South Africa and identifies Qatar as a growing hub of horn trafficking. Globally, total seizures and weight of seizures have dropped, which could be due in part to protection measures. However, it could also be a result of better smuggling or the fact that there are fewer rhinos left to poach. Clearly a closer examination of this trend is needed.

Beyond the IUCN/TRAFFIC rhino status report, 2025 is an important year for rhino conservation policy. The 20th Conference of the Parties (CoP) of signatories to CITES, the global wildlife trade agreement, takes place late in 2025 and provides an opportunity to review the progress of global rhino conservation efforts. During the CoP, the International Rhino Foundation (IRF) and Save the Rhino International will facilitate a panel discussion with rhino conservation, wildlife trade and law enforcement experts, as well as representatives from rhino range states and CITES Parties affected by the illegal rhino horn trade. We hope this side event will help shape the broader narrative around rhino conservation at CoP20 and influence decisions on key agenda items related to trade and enforcement in particular.

Additionally, rhinos will be in the spotlight at the World Conservation Congress in Abu Dhabi in October. The proceedings include a motion highlighting the urgent need for conservation actions to secure Indonesia’s remaining populations of Critically Endangered Javan and Sumatran rhinos. The motion encourages the Government of Indonesia to aim for rapid population growth through scientific management and calls on donors to provide adequate financial resources to help enable the recovery of these important ecosystem engineers.

IRF has prepared comprehensive recommendations for rhino range states and the international community to help ensure rhinos survive and, hopefully, thrive well into the future. To read IRF’s recommendations for conservation of all five rhino species, scroll to the bottom of this report.

*These are the latest numbers from the “African and Asian Rhinoceroses – Status, Conservation and Trade” report produced by the International Union for Conservation of Nature Species Survival Commission’s African Rhino Specialist Group, Asian Rhino Specialist Group and TRAFFIC, (IUCN/TRAFFIC report).

**While the numbers in the 2025 IUCN/TRAFFIC global rhino population report are the most recent available, not all countries provided new estimates and, for various reasons, it is difficult to obtain exact population counts.

African Rhinos

Africa is home to the world’s populations of black and white rhinos. At the end of 2024, there were an estimated 22,540 rhinos on the continent – 6,788 black rhinos and 15,752 white rhinos. Black rhino numbers increased by 5.2 percent since 2023, while white rhinos declined by 1,712 individuals between 2023 and 2024.

In 2024, 516 incidents of poaching were recorded in Africa – less than the 540 incidents documented in 2021 at CoP19. Of the 516 poaching incidents, 81.4 percent occurred in South Africa. The average yearly poaching rate in Africa fell to 2.15 percent of the total population in 2024.

From the end of 2021 to the end of 2024, 1,849 southern white rhinos were killed by poachers, a yearly average of 2.79 percent of the population.

Between the end of 2021 and the end of 2024, eight eastern black rhinos were killed by poachers; 143 south-central black rhinos were illegally killed; and 212 south-western black rhinos were killed.

White Rhino

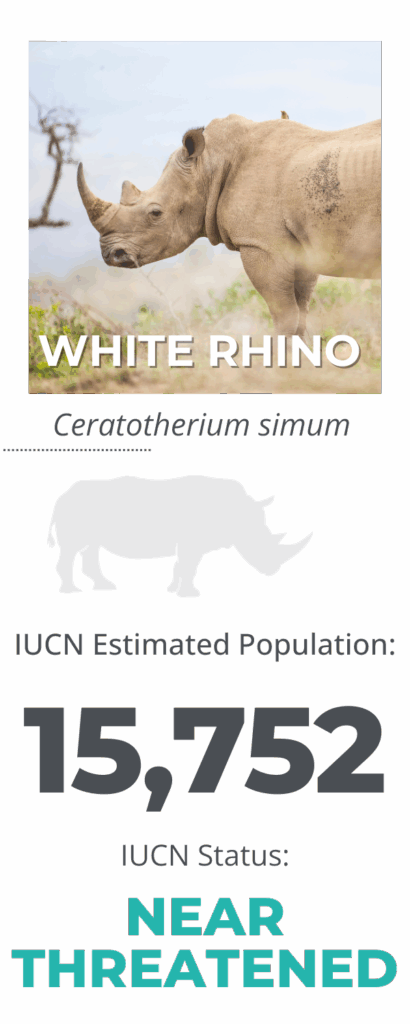

IUCN Estimated Population and Status: 15,752 ; Near Threatened

White rhinos (Ceratotherium simum) are the most populous of the five rhino species with approximately 15,752 animals across 13 countries in Africa. There are two white rhino subspecies, southern (C.s. simum) and northern (C.s. cottoni), but as there are only two northern white rhinos left in the world – both females – that subspecies is considered functionally extinct.

Around the start of the 20th century, there were less than 100 white rhinos in the world. By 2012, that number had rocketed to more than 21,000. Then, between 2012 and 2021, their high population made them the main target for rhino poachers. As a result, white rhino numbers declined by 24% during this period, falling to an estimated 15,942.

The white rhino population grew from 15,942 in 2021 to 16,834 in 2022, marking a 3.5 percent increase. In 2023, the population rose again to 17,464, reflecting a further 3.7 percent growth. However, by the end of 2024, the number of white rhinos in Africa dropped to 15,752, marking a significant decline in the African rhino population.

Black Rhino

IUCN Estimated Population and Status: 6,788 ; Critically Endangered

Black rhinos (Diceros bicornis) live in 12 countries in Africa, totaling an estimated 6,788 individuals. There are three subspecies of black rhinos. By the end of 2024, there were 2,597 south-western black rhinos (D. b. bicornis); 1,471 eastern black rhinos (D. b. michaeli); and 2,720 south-central black rhinos (D. b. minor).

A fourth subspecies, the western black rhino (D.b. longipes), was declared extinct in 2011; its last evidence of existence was in Cameroon in 2006.

Black rhinos were once the world’s most populous rhino species, with as many as 100,000 throughout Africa in 1960. By 1970, poaching had driven the black rhino population down to around 65,000. Their numbers continued to plummet, reaching a low of roughly 2,300 individuals by the mid- 1990s.

Now, even in the face of continued poaching pressure, black rhino populations are holding steady thanks to powerful protection and management strategies. Although populations can fluctuate year by year, the increase in numbers is encouraging.

A recent IUCN assessment of the black rhino indicated a substantial potential for recovery. If current conservation management efforts continue, the IUCN maintains the population could grow to 8,943 by 2032.

African Rhino Populations and Poaching

| African Rhino Range Countries | Estimated Rhino Population, by species (As of the end of 2024, unless otherwise noted) | Last-Reported Rhino Poaching Count (All poaching figures cited are from 2022 through 2024.) |

Botswana | 345 rhino (25 black, 320 white) | 15 |

| Chad | 7 black rhino* *latest estimates were in 2023 | 0 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 1 white rhino* *latest estimates were in 2023 | 0 |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | 31 white rhino* *latest estimates were in 2023 | 1 |

| Eswatini | 124 rhino (62 black, 62 white) | 0 |

| Kenya | 2,102 rhino (1,059 black, 1,043 white) | 7 |

| Malawi | 66 black rhino | 2 |

| Mozambique | 58 rhino* (18 black, 40 white) *latest estimates were in 2023 | 1 |

| Namibia | 3,598 rhino (2,098 black, 1,500 white) | 255 |

| Rwanda | 71 rhino (34 black, 37 white) | 0 |

Senegal | 3 white rhino* *latest estimates were in 2023 | 0 |

| South Africa | 14,389 rhino (2,307 black, 12,082 white) | 1,367 |

| Tanzania | 268 black rhino | 0 |

| Uganda | 43 white rhino* *latest estimates were in 2023 | 0 |

| Zambia | 114 rhino (60 black, 54 white) | 4 |

| Zimbabwe | 1,320 rhino (784 black, 536 white) | 27 |

Inside the Black Market: The Global Trade in Rhino Horn

The trade and trafficking of rhino horn represents one of the most urgent conservation challenges we face. Driven by a complex interplay of cultural beliefs, socioeconomic issues and organized crime, this illegal trade has pushed rhino species to the brink of extinction.

“Despite global bans and increased protection efforts, poaching and illicit trafficking persist, raising critical questions about enforcement, education and international cooperation,” said Nina Fascione, executive director of the International Rhino Foundation (IRF). “At the heart of the crisis is persistent demand.”

Demand comes primarily from China and Vietnam. Currently, the largest driver of demand is for decorative carvings and trinkets like cups, bracelets and pendants. In traditional Chinese medicine, the horn is believed to have curative properties, primarily for reducing fevers. There is no scientific evidence to support this belief.

This demand has decimated rhino populations and is an ongoing threat. It recently led to the devastating killing of as many as 26 Critically Endangered Javan rhinos in Indonesia by a poaching gang between 2019 and 2023, wiping out potentially one-third of the estimated remaining population. It’s why Javan rhino numbers were so perilously low in the most recent global rhino population count from the International Union for Conservation of Nature, and why the white rhino population has declined since the last official count in 2022.

Socio-Political Complexities Make it Hard to End Poaching

Africa is home to the majority of the world’s rhinos and where most rhino poaching occurs. To help curb the killings, IRF actively supports strategically selected rhino reserves and security clusters that have demonstrated a strong commitment to protecting their rhino populations. By investing in proven, evidence-based interventions, while also encouraging innovation and forward-thinking approaches, IRF is making meaningful and measurable contributions to rhino conservation and protection efforts in Africa.

Poaching is a complex organized crime requiring a whole-of-government solution – yet the bulk of the response continues to fall on the conservation sector. In South Africa, systemic corruption at the highest levels of national security has eroded trust and weakened law enforcement efforts. The South African Police Service is reportedly operating with severe detective shortages, staggering case backlogs and limited resources. Only a few investigators are assigned to rhino and wildlife crime.

An official unemployment rate of 32.9 percent, persistently high crime levels, dysfunctional government systems and steep budget cuts compound the crisis in South Africa. Organized crime thrives in this environment, bolstered by embedded corruption including among reserve staff, limited investigative and prosecutorial capacity, slow court proceedings and the routine granting of bail to repeat offenders.

Corruption among reserve staff can take the form of rangers or other park staff providing information on the location of rhinos to poaching syndicates or standing down when poaching operations are happening. In some cases, rangers have engaged in poaching.

“Rhino reserves are not only fighting poaching on the ground but are also left to contend with broader issues such as poverty, entrenched criminality and collapsing municipal services in communities along their boundaries,” said Elise Serfontein, IRF’s South Africa advisor and founding director of Stop Rhino Poaching, a South Africa-based organization Serfontein created in 2010 as a response to the poaching crisis and is a close partner to IRF.

“Hard-won conservation gains and their sustained investment into social upliftment projects are being overwhelmed by the scale of the challenge – particularly in areas like the Greater Kruger landscape, which borders densely populated communities numbering in the millions,” Serfontein added.

Understanding Trafficking Networks

Rhino horn smuggling relies on transnational criminal networks which smuggle horns across borders through corrupt officials, forged documents and elaborate concealment techniques.

On the transit side, in ports of exit and entry, officials will ensure cargo or luggage is not inspected so horn can pass through customs. At international borders, law enforcement will look the other way as horn is smuggled through.

The smuggling routes are varied and shifting. Horn is primarily smuggled by air since traffickers can hide small amounts in luggage and even small quantities are still very valuable. After rhinos are poached in Africa, their horns are often shipped out of Mozambique and Angola and might pass through United Arab Emirates and Qatar, which have common routes for international flights, as well as Vietnam, Laos, Thailand and Malaysia.

These trafficking routes can intersect with other illegal activities, such as drug and arms trafficking, highlighting the broader criminal ecosystem involved.

The Recommended Path Forward

There are several key measures IRF supports in the battle against rhino poaching and illegal trade and trafficking. One is on the law enforcement side. While it’s important to hold the on-the-ground poachers accountable, we need law enforcement agencies to target and apprehend the masterminds that sit higher up the chain of these criminal networks.

Additionally, poachers need to be arrested, convicted and imprisoned, with strong sentences to deter them from becoming repeat offenders. This is occurring in Indonesia, where the longest sentences ever given for wildlife offenses in the country, up to 12 years in jail, were handed down to the poachers of the Javan rhinos killed between 2019 and 2023.

Demand reduction is a third critical aspect of stemming the poaching crisis. A lot of good work has been done to reduce demand for rhino horn, and there appears to be less horn moving into Asian countries than in the past, but that work must continue.

Another important element is international cooperation and information sharing. Many countries are doing better with enforcement within their own borders, but these networks are vast and span the globe, so there must be a collaborative international effort. Part of this effort includes financial investigations – following the money – to map out worldwide criminal networks.

Demand reduction campaigns should focus on changing the behavior of would-be or current horn consumers. Such campaigns include media advertising, public service announcements and working with influential stakeholders so the right messengers are spreading the word that they don’t want or need these wildlife products in medicines. Those efforts must go hand in hand with enforcement, because without penalties for consumption, there will be no change. Along with enforcement, behavior change efforts will not be effective without major policy changes and government support in areas where rhino horn is consumed.

The battle against rhino horn trafficking doesn’t just test the global community’s will to save these species – it offers a bold challenge for nations to work together to confront transnational wildlife crime and preserve the biodiversity that is integral for a thriving planetary ecosystem.

The fate of rhinos depends on whether the international community can shift from exploitation to stewardship before it’s too late. By raising awareness and advocating for strong, science-based policies, we can help ensure future generations inherit a world where rhinos still roam free.

Asian Rhinos

Asia is home to three rhino species – greater one-horned, Sumatran and Javan.

As of March 2025, there were 4,075 greater one-horned rhinos on the continent, with 3,323 in India and 752 in Nepal. The numbers were slightly higher than the 4,014 reported in 2022.

Rhino populations in India and Nepal have increased steadily since 2007. In India, thanks to continued successful conservation work and strong law enforcement, the population of greater one-horned rhinos increased to 3,323 by 2024 from 2,150 in 2007. Nepal’s greater one-horned rhino population also displayed consistent increases, growing to 752 in 2024, up from 413 in 2007.

In India, nine greater one-horned rhinos were killed by poachers from January 2021 to December 2024. In Nepal, four greater one-horned rhinos were illegally killed in that same period. In the Indian state of Assam, where the majority of the country’s rhinos reside, four rhinos were poached from 2022 to 2024. Arrests were made in all four killings and the cases are working through the courts. All the main players in each case were identified by IRF’s intelligence specialist.

In Indonesia – home to the only remaining populations of Critically Endangered Sumatran and Javan rhinos – the recovery of the species looks very different. Javan rhino numbers rose modestly to 76 by 2021, up from 40 to 50 individuals in 2007. Then the population dropped to roughly 50 in 2024 due to the poaching of up to 26 rhinos from 2019 to 2023.

The Sumatran rhino has been declining for more than a decade. After having between 180 and 200 individuals in 2007, there are just 34 to 47 today. However, after a pair of highly trained detector dogs sniffed their way through Sumatra’s Way Kambas National Park, there is new hope for this species. The dogs found what is thought to be scat from Sumatran rhinos in an area where they have not been identified by monitors, surveys or camera traps for years. DNA testing still needs to confirm the findings, but it will be a major conservation success if these reclusive animals are proven to be living in the national park. The Government of Indonesia has been integral to the process and the government’s support for this project is very much appreciated.

The dire state of Indonesia’s rhinos has pushed the World Conservation Congress to propose a motion at its October 2025 meeting in Abu Dhabi highlighting the critical endangerment of Sumatran and Javan rhinos. The motion aims to bring attention and resources from the international community to help the Government of Indonesia secure the remaining populations of these rhinos.

Greater One-horned Rhino

IUCN Estimated Population and Status: 4,075 | Vulnerable

Greater one-horned rhinos (Rhinoceros unicornis) live in India and Nepal. In the past 100 years, the greater one-horned rhino population has recovered significantly from less than 100 individuals to more than 4,000 today.

In February 2025, officials at Jaldapara and Gorumara National Parks in West Bengal, India, carried out population surveys. Jaldapara reported an increase of 44 rhinos since the last survey, while Gorumara saw a rise of nine rhinos.

While greater one-horned rhinos are increasing, they are still classified as Vulnerable. Poaching is a constant threat. From January 2022 to April 2025, 52 suspects were arrested in connection with crimes against greater one-horned rhinos.

Greater one-horned rhinos no longer live in much of their historic range, though they are returning to some areas thanks to habitat restoration and protected corridors. Another major threat to greater one-horned rhinos is the abundance of invasive species, which outcompete the native plants rhinos depend on to survive and restrict the amount of available habitat.

Javan Rhino

IUCN Estimated Population and Status: 50 | Critically Endangered

There are thought to be 50 Javan rhinos (Rhinoceros sondaicus) left in the wilds of the Indonesian island of Java after up to 26 were killed by poaching gangs. In 2023, police near Ujung Kulon National Park were notified that camera traps – the primary tool for monitoring Javan rhinos – were missing. Rhino activity had declined as well. Then, footage from other cameras revealed armed poachers had entered the national park.

These findings led to the identification of 13 suspects from a village close by, including two brothers who headed up poaching gangs. The loss of the 26 rhinos resulted in a 33 percent reduction of the total population of Javan rhinos. After an investigation in 2024, Indonesian police arrested and secured convictions against the poachers. The courts imposed fines and handed down sentences of up to 12 years for the perpetrators.

Sumatran Rhino

IUCN Estimated Population and Status: 34 to 47 | Critically Endangered

There are up to four isolated populations and as many as 10 subpopulations of Sumatran rhinos (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) left in Indonesia. Only one of these wild populations, in Gunung Lesuer, is believed to have enough individuals to be reproductively viable. The total population in Indonesia is estimated to be 34 to 47.

However, the news of detector dogs finding what is likely Sumatran rhino scat in Way Kambas National Park provides hope for this Critically Endangered rhino. Additionally, the breeding program at the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary, a protected, semi-wild facility in Sumatra, continues its breeding efforts to create an insurance population of rhinos.

Despite protection, the species has decreased by more than 70 percent over the past 30 years and was declared extinct in the wild in Malaysia in 2015. It now exists only in Indonesia. Living in fragmented rainforest habitats makes it difficult for breeding-age animals to encounter one another.

Asian Rhino Populations and Poaching

| Asian Rhino Range Countries | Estimated Rhino Population, by species as of early 2025 | Last-Reported Rhino Poaching Count |

| India | 3,323 greater one-horned rhino | 9 from 2021 through 2024 |

| Nepal | 752 greater one-horned rhino | 4 from 2021 through 2024 |

| Indonesia | 84 to 97 rhino (~50 Javan, 34-47 Sumatran) | Up to 26 Javan rhinos reported poached from 2019-2023 |

Innovations and Developments in Rhino Conservation

Trimmed Horns Help Prevent Rhino Poaching

At IRF, we are proud to sponsor cutting-edge research into new methods of monitoring rhinos and preventing poachers from killing these important animals.

IRF supports horn trimming, when combined with other proven security measures, to help stop rhino killing. We have provided significant funding in grants for white and black rhino horn trimming operations in South Africa’s Kruger National Park and other rhino reserves.

As a science-based organization, we were encouraged when a study came out earlier this year showing rhinos that had their horns trimmed were less likely to be killed by poachers.

The study analyzed data from 11 reserves in the Greater Kruger region – home to roughly 25 percent of all of Africa’s rhinos – from 2017 to 2023. In the areas where rhino horns were trimmed, poaching was reduced by 78 percent.

That result is compelling evidence that horn trimming works, but horn trimming alone will not stop poaching. As IRF Executive Director Nina Fascione told The Washington Post when the study was released, poachers may still target rhinos for the nub of horn that remains after trimming.

Even so, Nina pointed out that a live rhino without a horn is far better than a dead rhino without a horn. When horn trimming is combined with daily monitoring, safe and protected habitat, engagement with local communities and other safeguards, we give rhinos their best chance at survival.

New Tool for Rhino Tracking

Traditionally, methods like ear tags, horn implants and ankle collars have been used to track and monitor rhinos. However, with such massive animals roaming the bush, the ear and ankle devices are sometimes damaged. So far, horn implants have shown particular promise, but they can only be used on animals with horns large enough to contain transmitters.

To help provide a solution, IRF funded efforts by Munywana Conservancy in South Africa to develop new technology for addressing the challenge of monitoring horn-trimmed rhinos.

Through testing, the Conservancy’s researchers found they could effectively glue GPS tracking devices, known as pods, to the posterior horn stumps of black and white rhinos. Researchers paid special attention to fitting the pods to rhinos, particularly for large white rhinos, as the increased horn stump size and infighting between dominant bulls could have caused some pods to become detached.

These GPS devices do not cause the rhinos any injury and they fall off as the horn grows back.

While further testing will be done, the GPS pods could offer an exciting new tool for remotely monitoring horn-trimmed rhinos with no risk of injury to the animals.

AI bolsters conservation in rhino reserves

Thanks to funding from IRF, our partner reserves have successfully deployed 66 artificial intelligence-enhanced rhino foot collars, significantly expanding monitoring coverage in high-risk areas across South Africa.

This technology is known as the Rouxcel Rhino Watch monitoring system. It was implemented in four IRF-supported rhino reserves including Lapalala Wilderness Reserve, Addo Elephant National Park and Kwandwe Private Game Reserve.

The new monitoring system detects and transmits alerts in real-time about abnormal rhino behavior, which could indicate poaching attempts. IRF’s funding also supported the purchase of 79 internet gateways, devices that enable communication between a private network and the public internet.

The Rouxcel system is enhancing the successful security measures already in place in the reserves and is one of multiple interventions used to protect these rhinos. Thanks to this enhanced tracking and a quicker deployment of ground and drone response teams, all user reserves have continued to have little to no known rhino poaching.

IRF Recommendations

The following are IRF’s recommendations on what nations and the international community should do to save the world’s rhinos.

- The global community must come together to support rhino range countries as the front lines for battling rhino poaching and conserving rhinos.

- All nations and international bodies that care about the survival of rhinos should collaborate and coordinate to provide funding and support rhino range countries where rhinos are most endangered, like Indonesia, as such countries are the front line for preventing the extinction of rhino species.

- Efforts to reduce demand for rhino horn must be prioritized.

- Demand reduction campaigns should focus on behavior change and include media advertising, public service announcements and influential stakeholders for effective messaging. Enforcement of penalties, major policy changes and government support in countries where rhino horn is consumed are essential. At a global level, an increased effort must be made in undertaking investigations of horn transport conduits and horn markets. More focus should be devoted to international condemnation of countries that are doing little to control trade in illegal wildlife products.

- Local communities must be engaged to reduce threats to rhinos and ensure the sustainability of conservation efforts.

- We cannot succeed in protecting rhino populations unless the people who live alongside rhinos benefit from and support conservation efforts. When communities thrive, it helps wildlife thrive. We must work to develop sustainable income opportunities that strengthen local communities and reduce pressure on protected areas and endangered species.

- Governments must address apathy and corruption in their own ranks.

- Primary issues facing rhino conservation in many range states continue to be corruption, apathy and lack of accountability of government officials. Investigations have decreased in recent years due to a lack of experienced investigative capacity, reduced enforcement budgets and strained operational resources, lackluster political will and sub-optimal international cooperation. Range country and consumer country governments should focus on investigation and prosecution of internal corruption.

- Greater emphasis is needed on improving relationships between state and private sector stakeholders.

- These operations are critical in enabling preemptive actions against poachers before they can start hunting rhinos within a protected area, or to at least follow up on them after incursions. However, they must be managed by experienced, trustworthy and professional staff.

- In Asia, rhinos need better habitat management and restoration.

- In India, Nepal and Indonesia, rhino population growth has been constrained by a lack of adequate habitat. In India and Nepal, many of the parks that would provide habitat for rhinos have been overrun by invasive species. Natural rhino deaths are higher than poaching deaths. Some of the deaths are from eating invasive plants, while others result from males fighting over suitable habitat, especially where rhino populations are growing. In Indonesia, there is enough habitat for the existing, meager populations of rhinos, but if we want to expand those populations, more suitable habitat is needed. Many of the protected areas where rhinos live are ecologically degraded, and if more rhinos are introduced, there may not be enough space for them. Invasive plants must be removed, habitat should be restored and corridors for safe movement must be expanded.

- Rhinos need more safe habitat to survive in Africa.

- There is plenty of adequate habitat available for rhinos in Africa – the problem is there’s not enough safe habitat. Rhinos can thrive in the appropriate habitat, but if the environment around them is not safe, they will not survive. IRF urges strong laws and protections to create safe habitat for rhinos.

- Private rhino owners must provide accurate and complete population figures to officials.

- The reluctance to provide population numbers and stockpile data is often driven by security concerns, fear of poaching, mistrust over how the information will be used and frustration with regulatory scrutiny. While in some cases these concerns are understandable, they significantly impede efforts to develop an accurate and unified understanding of rhino populations — insight that is essential for effective conservation planning and response.

- Rhinos should be managed for biological productivity and not just for greater security in the face of poaching.

- Rhino population growth isn’t just limited by poaching, but also by low birth rates due to either overpopulation in some areas or insufficient rhino numbers in others, as well as the overall recruitment rate. Genetic erosion through inbreeding is an insidious problem within small rhino populations. To maintain viable populations in wild spaces, more global incentives such as biodiversity credits must be realistically developed to tip the balance in land use from practices that reduce wild space to factors that promote biodiversity conservation.

This report was prepared by the International Rhino Foundation from sources including the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora African and Asian Rhinoceroses – Status, Conservation and Trade report (August 2025), IUCN SSC’s African Rhino and Asian Rhino Specialist Groups and Traffic, along with input from IRF’s rhino range country advisors and partners.