Abstract

Background:

The diverse forms of unrecorded alcohol, defined as beverage alcohol not registered in official statistics in the country where it is consumed, comprise about one fourth of all alcohol consumed worldwide. Since unrecorded alcohol is usually cheaper than registered commercial alcohol, a standard argument against raising alcohol excise taxes has been that doing so could potentially result in an increase in unrecorded consumption. This contribution examines whether increases in taxation have in fact led to increases in consumption of unrecorded alcohol, and whether these increases in unrecorded alcohol should be considered to be a barrier to raising taxes. A second aim is to outline mitigation strategies to reduce unrecorded alcohol use.

Methods:

Narrative review of primary and secondary research, namely case studies and narrative and systematic reviews on unrecorded alcohol use worldwide.

Results:

Unrecorded alcohol consumption did not automatically increase with increases in taxation and subsequent price increases of registered commercial alcohol. Instead, the level of unrecorded consumption depended on: a) the availability and type of unrecorded alcohol; b) whether such consumption was non-stigmatized; c) the primary population groups which consumed unrecorded alcohol before the policy change; and d) the policy measures taken. Mitigation strategies are outlined.

Conclusions:

Potential increases in the level of unrecorded alcohol consumption should be considered in the planning and implementation of substantial increases in alcohol taxation. However, unrecorded consumption should not be considered to be a principal barrier to implementing tax interventions, as evidence does not indicate an increase in consumption if mitigation measures are put in place by governments.

Keywords: Unrecorded alcohol, taxation, surrogate, homebrew, smuggling, counterfeit

Introduction

Alcohol use has been one of the major risk factors for mortality and burden of disease globally (Rehm & Imtiaz, 2016), and a substantial proportion of the alcohol consumed is so-called unrecorded alcohol (about 25%; for 2017: 1.7 litres adult pure alcohol per capita out of 6.5 litres (Manthey et al., 2019)). Unrecorded alcohol is consumed as an alcoholic beverage, but is not registered in official statistics as beverage alcohol for sales, production, or trade in the country where it is consumed (Lachenmeier, Neufeld, & Rehm, 2021; Okaru et al., 2019). Hence, the term “unrecorded” is used to describe it. At a global level, unrecorded consumption has remained more or less constant over the past 20 years ((World Health Organization, 2004, 2011, 2014, 2018), with proportions varying between 22% in 2007 and 25% in 2019).

Typically, the use of unrecorded alcohol has a clear association with economic wealth, both within and between countries: the higher the economic wealth, the lower the proportion of unrecorded alcohol consumption (Rehm et al., 2016). Mouthwash provides an example of unrecorded alcohol use in Canada: mouthwash with ethanol concentrations of nearly 30% is sometimes consumed by homeless or people of low socioeconomic status, as a less expensive alternative to beverage alcohol ((Erickson et al., 2018); see also (Lachenmeier, Monakhova, Markova, Kuballa, & Rehm, 2013)). Sales of mouthwash are taxed (value-added tax) and thus registered, and the government is aware of its use as an alcohol substitute. However, it is clearly unrecorded alcohol, as mouthwash is not registered as alcoholic beverage and thus no alcohol excise taxation applies to it.

The alcohol industry’s own statistics cover only the “non-commercial” or “non-beverage” categories of unrecorded alcohol (Adelekan, 2008), while in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) nomenclature (World Health Organization, 2018) the umbrella term “unrecorded alcohol” is used, which is wider and covers for example cross-border shopping. The WHO definition will be used in this review.

Unrecorded alcohol has long been recognized as a public health, social, and financial problem (Probst et al., 2019; Rehm et al., 2014). The implications of its use and production extend far beyond its effects on health, as the legal, agricultural, and financial sectors, as well as trade and international relations, and the interests of population subgroups such as women brewers (McCall, 1996; Mkuu, Barry, Swahn, & Nafukho, 2019), are profoundly affected as well.

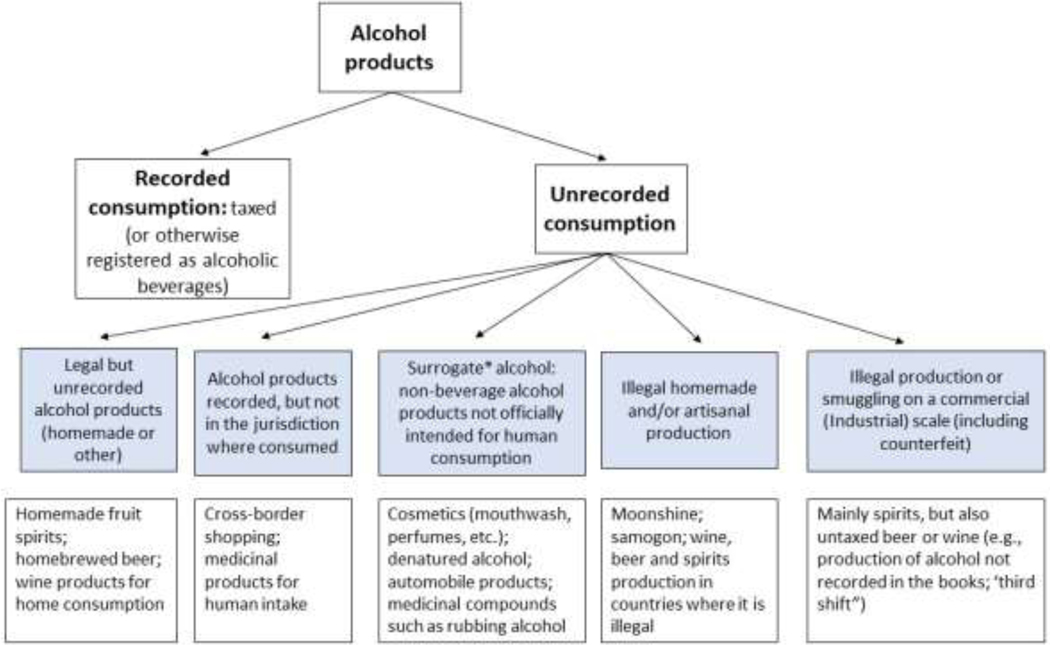

Unrecorded alcohol is comprised of various categories (Figure 1), and the relative importance of these varies widely between, and sometimes even within, countries and cultures. The major categories of unrecorded alcohol are (i) legal but unrecorded alcohol products; (ii) alcohol products recorded, but not in the jurisdiction where consumed; (iii) surrogate alcohol, i.e., non-beverage alcohol products not officially intended for human consumption; (iv) illegal homemade artisanal production; and (v) illegal production or smuggling on a commercial (industrial) scale, including counterfeiting (brand fraud).

Figure 1.

Categories of unrecorded alcohol (first row: categories; second row: examples); updated from (Lachenmeier, Neufeld, & Rehm, 2021))

*Surrogate alcohol may be intended for human consumption, but intentionally not declared as such in order to evade taxes. For this form of surrogate alcohol, the term pseudo-surrogate is sometimes used.

The distinctions between categories (iv) and (v) are somewhat fluid. To give just one example— in Eastern Africa, some artisanal spirits producers have grown into larger enterprises, with their products likely to be industrially packaged and distributed in the future (GS Uganda, 2018). Additionally, the internet may be a medium where many different forms of unrecorded alcohol are sold, including to minors (Il’ina, 2018; Neufeld, Lachenmeier, Walch, & Rehm, 2017), thus violating youth protection laws.

While recorded alcohol consumption can be measured via sales and taxation (as alcoholic beverages) or via production, export and import records and registers, the monitoring and surveillance of unrecorded alcohol consumption remains fragmented and underdeveloped (Rehm & Poznyak, 2015). The figures on unrecorded consumption in the WHO’s monitoring system are currently statistically modelled based on expert judgements, the limited survey data available (Probst et al., 2019), and extrapolations from single-country studies (Probst et al., 2019; Probst, Manthey, Merey, Rylett, & Rehm, 2018; Rehm & Poznyak, 2015). The country-specific estimates for the volume of unrecorded alcohol consumption in 2015 can be found in Probst et al. (2019). For various reasons—especially insufficient sampling frames and potential underreporting in surveys—these estimates are considered to be conservative, and may substantially underestimate the true consumption level of unrecorded alcohol (Lachenmeier & Walch, 2018) in some parts of the world.

In the academic literature, unrecorded alcohol is often discussed primarily from a health perspective (Lachenmeier, Neufeld, & Rehm, 2021). However, unrecorded alcohol is also an important issue in policy discussions, since it often seen as presenting a key barrier to increasing the price of recorded alcoholic beverages via taxation measures. From an alcohol policy perspective, raising the price of alcohol via taxation or other means such as minimum unit pricing is a key evidence-based strategy for reducing alcohol consumption (Chisholm et al., 2018; World Health Organization, 2017). In fact, the alcohol industry has repeatedly brought unrecorded alcohol into the debate as a barrier for taxation increases (International Alliance for Responsible Drinking (IARD), 2017), claiming that an increase in the use of (the potentially more dangerous) unrecorded alcohol will result as a reaction by consumers to any increase in taxation on recorded alcohol. They also point out that unrecorded alcohol, by definition, is not subject to the same government regulations that the alcohol industry must adhere to when producing beverage alcohol, such as requirements for quality control or warning labels.

This review outlines the evidence for the impact of taxation measures on unrecorded alcohol consumption, and the extent to which the availability of unrecorded alcohol means that potential goals of taxing beverage alcohol may not be reached. After outlining the methodology, the review is divided into the following main sections: 1) an overview of how unrecorded alcohol may impact on the implementation of policies, and 2) mitigation strategies for addressing unrecorded alcohol production and consumption.

Methods

This is a narrative review of primary and secondary research, based on systematic and other reviews on unrecorded alcohol consumption (Lachenmeier, Gmel, & Rehm, 2013; Lachenmeier, Neufeld, & Rehm, 2021; Okaru et al., 2019; Rehm et al., 2014), including reviews by the alcohol industry or by researchers it has supported (International Alliance for Responsible Drinking (IARD), 2017, 2018; Nelson & McNall, 2016, 2017) and reviews on taxation strategies (Sornpaisarn, Shield, Österberg, & Rehm, 2017), as well as several country case studies.

For the country-specific case studies, the same search terms for unrecorded alcohol used in the study by Lachenmeier and colleagues (Lachenmeier, Neufeld, & Rehm, 2021) were applied, but with the addition of the search terms “pricing”, “price”, “tax” and “taxation”, and the country name, as Lachenmeier and colleagues focused on chemical composition and health consequences. The countries for the case studies were chosen by the authors to: a) include the countries with the most striking taxation changes in the past decade, b) reflect different forms of unrecorded alcohol, and c) represent different regions of the world.

Each country case study was first reviewed by one of the authors who had specific experience in the field of unrecorded alcohol in that particular country, prior to being discussed by the whole team of authors.

Why does unrecorded alcohol matter for tax implementation purposes?

All categories of unrecorded alcohol matter for the implementation of excise taxation on alcohol, as unrecorded alcohol is generally considerably cheaper than recorded alcohol and does not produce revenue for the government (Lachenmeier, Neufeld, & Rehm, 2021). This is self-evident for the category of unrecorded alcohol purchased via cross-border shopping: some people travel to another country specifically to buy alcohol there due to its lower price, or shop for alcohol in airport duty-free shops when travelling.

However, the appeal of a price differential is not limited to the purchase of unrecorded alcohol in the cross-border shopping category. Almost all other categories of unrecorded alcohol—with the possible exception of some boutique artisanal production of speciality wines, spirits or craft beers—have been found to be considerably cheaper than regular recorded beverage alcohol (for instance: (Bobrova et al., 2009; Estonian Institute of Economic Research, 2005; Gamburd, 2008; Gururaj, Gautham, & Arvind, 2021; Lachenmeier, Leitz, et al., 2011; Lang, Väli, Szűcs, Ádány, & McKee, 2006; Liyanage, 2008; Mkuu et al., 2019; Neufeld, Wittchen, Ross, Ferreira-Borges, & Rehm, 2019; Pärna, Lang, Raju, Väli, & McKee, 2007)). As a result of this price differential, any policy which aims to use tax increases on recorded alcohol in an effort to reduce consumption will only reach its full potential if there is little switching by drinkers to the less expensive unrecorded alcohol as a result of the tax hike.

A price differential, ceteris paribus, would mean that any substantial change in taxation should be accompanied by changes in unrecorded consumption in the same direction; that is, an increase in taxation should be associated with an increase in unrecorded consumption, and a decrease in taxation should be associated with a decrease in unrecorded consumption. In fact, reducing alcohol taxes has even been proposed by some economic operators (particularly from the alcohol industry) to be a good means by which to reduce unrecorded alcohol consumption (International Alliance for Responsible Drinking (IARD), 2018). Zimbabwe is often cited here, since a 1995 tax increase led to an increase in unrecorded alcohol use, and a decrease in recorded alcohol use and government revenue ((Jernigan, 1999), p. 169; see also (Room, Jernigan, et al., 2013)).

The loss of government revenue is not the only argument put forth for reducing unrecorded consumption by alcohol industry interests: health consequences are often cited as well. It has been argued, mainly in industry and industry-sponsored research publications, that unrecorded consumption incurs more harm than recorded consumption per litre of pure alcohol. The argument is that even if less alcohol is consumed overall after a tax increase, it does not necessarily mean that the level of harm will be reduced (Skehan, Sanchez, & Hastings, 2016). In summary, according to these arguments, increases in alcohol taxation should be avoided or minimized, as they inevitably lead to increases in unrecorded consumption, which not only reduce government revenue, but also increase the burden of disease.

However, there is a dearth of evidence that tax increases lead to substantial increases in unrecorded consumption. We therefore detail a number of case studies to provide relevant evidence on the context and outcomes related to unrecorded alcohol use following increases in taxation.

Unrecorded alcohol and health

While the production of unrecorded alcohol does not allow for quality control of its ingredients by the responsible authorities in the same way as for commercially available alcoholic beverages, several reviews have revealed that in most cases this does not pose a threat to burden of disease over and above the effects of ethanol (that is, pure alcohol; for reviews, see (Lachenmeier, Neufeld, & Rehm, 2021; Rehm et al., 2014; Rehm, Kanteres, & Lachenmeier, 2010)). The evidence for these conclusions includes examples from many countries, including Eastern European countries, where more detrimental health consequences of unrecorded alcohol were previously postulated (examples: (Bujdosó et al., 2019; Pál et al., 2013); but see the argumentation of (Lachenmeier, Walch, & Rehm, 2019)).

The one major exception to this is in cases where there is an addition of methanol (Rehm et al., 2014). Other potential contaminants, such as metals or aflatoxin (Lachenmeier et al., 2021), may occur, but comparative risk analyses showed that the additional risk from these contaminants is low compared to the risk of ethanol alone (for further details, see (Lachenmeier, Neufeld, Kilian, et al., 2021; Lachenmeier, Neufeld, & Rehm, 2021)). It follows that, from a public health perspective, the goal of any alcohol control intervention should be to reduce total per capita consumption (Poznyak et al., 2013; Rehm, Crépault, Wettlaufer, Manthey, & Shield, 2020) -- the sum of all recorded and unrecorded consumption -- since this will, without a doubt, result in a reduction in alcohol-attributable harm. Therefore, the public health aim after any implementation of tax increases should be a net decrease in total per capita consumption, whatever may happen to the ratio of unrecorded to recorded alcohol. In addition, it may be important to monitor and check that the overall reduction in alcohol use was associated with a gain in health (i.e., reductions in hospitalizations and mortality).

Case studies on changes in taxation and unrecorded alcohol consumption

In order to examine potential impacts of taxation changes on the level of use of unrecorded alcohol, we examined a number of case studies:

Lithuania and Russia are countries with recent substantial increases in alcohol taxation linked to marked decreases in all-cause mortality (Lithuania: (Štelemėkas et al., 2021);

Russia: (Neufeld et al., 2020; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2019));

Nordic countries where countries changed their taxation levels in part due to a fear of increased cross-border shopping after joining the European Union (Room, Bloomfield, et al., 2013); and

Kenya and Botswana as two examples from sub-Saharan Africa, where high overall levels of unrecorded consumption are often cited as the reason why taxation increases are ineffective in that region (Ferreira-Borges, Parry, & Babor, 2017).

Lithuania

In Lithuania, unrecorded consumption has been relatively low over the past years: between 5% and 8% for all categories except for cross-border shopping (Drug Tobacco and Alcohol Control Department, 2013; Health Research Institute, 2018; Lang & Ringamets, 2018). With such a history, it is unlikely that infrastructure would have been in place for unrecorded alcohol to suddenly be produced and consumed in Lithuania in much higher quantities. However, in recent years there seems to have been a net increase in cross-border trade with neighbouring Poland and Latvia, with Latvia having the lowest alcohol prices of all Baltic countries in the past few years (LRT English, 2019; Pärna, 2020). The exact magnitude of this cross-border trading is not clear, as the two countries reported different estimates based on small sample surveys of people crossing the border. In summary, while Baltic governments still see a need to negotiate on cross-border trade issues, the main public health and fiscal goals of the increase in alcohol excise taxes in Lithuania have already been realized. After a significant increase in excise taxes on March 1, 2017, there were marked reductions in alcohol consumption and in alcohol-attributable mortality, and even on all-cause mortality (Štelemėkas et al., 2021). In addition, the government’s annual alcohol excise tax revenue rose by nearly 27% for 2017 alone (Lithuanian Tobacco and Alcohol Control Coalition, 2020).

Russia

In Russia, the history of unrecorded alcohol has been different. Traditionally, Russia has been a country with a large percentage of unrecorded alcohol consumption, estimated, in fact, as being larger at times than recorded consumption (Nemtsov, 2011; Radaev, 2017; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2019). The statistics for recorded and unrecorded alcohol have at times been inconsistent for this country, as official statistics of retail sales of alcohol for some years exceeded recorded production and imports of alcohol, and far exceeded taxed alcoholic beverages (Khaltourina & Korotayev, 2015).

Several different forms of unrecorded alcohol exist in Russia, with different consumers, often from different parts of the social hierarchy. For instance, the traditional home-made vodka (samogon) is an ambiguous and broad category, spanning from artisanal traditional spirits that are often perceived to be superior to at least the cheaper commercial brands, to cheaply produced drinks that are sold or used as in-kind payment in rural communities, and are often associated with heavy drinking (Nemtsov, 2011; Neufeld, Wittchen, & Rehm, 2017). People who drink samogon therefore come from diverse socioeconomic strata. In contrast, consumption of cheap counterfeit alcohol is more often limited to people of lower-socioeconomic strata who consume heavily (Kotelnikova, 2017), and surrogate alcohol is clearly linked to social downward drift, being consumed mainly by marginalized people with alcohol dependence when no other alcohol is available (and/or commercial alcohol is too expensive (Bobrova et al., 2009; Neufeld et al., 2019)). Smuggled and “third-shift” alcohol (alcoholic beverages produced in factories but not declared to the tax authorities), as long as they are recognized as unrecorded alcohol by the consumer, can be placed somewhere in the middle of the continuum.

Measures against all these forms of unrecorded consumption have been implemented (Neufeld & Rehm, 2018; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2019), such as the introduction of taxes on any ethanol-containing liquids in the form of an excise tax, and the adoption of new, more effective (less toxic and more odorous) denaturizing additives for industrial alcohol. One of the main measures put in place in Russia was the introduction in 2006 of the EGAIS (Unified State Automated Information System), a monitoring and surveillance system under the specially formed government control body, the Federal Service for Alcohol Market Regulation. This system has been revised and improved over time, and the current iteration includes an extension from the production level to the wholesale and retail trade levels in 2016.

The main aim of this monitoring system had initially been to ensure completeness and accuracy in accounting for the production of ethyl alcohol for alcoholic beverages, in order to gain more government control over the production process, ensure excise tax payments were made, and reduce production of illicit alcohol. The new system allowed comparisons between the officially produced alcohol volumes (plus imports) and the official sales of alcoholic beverages—and this revealed that more alcoholic beverages were being sold in the country than were officially being produced and imported. EGAIS required all sales outlets to be equipped with special cash registers in order to be licenced—a costly requirement which naturally reduced the density of sales outlets. It stopped alcohol sales in various small shops altogether, many of which were suspected of selling counterfeits and “third-shift vodka” (for more details on the EGAIS system, see Annex 2 of (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2019)). In addition, a number of other measures were introduced: prohibiting or limiting the sale of certain forms of surrogate alcohol (e.g., prohibiting sales from vending machines, setting minimum prices at the same level for beverage alcohol as for cosmetic lotions containing more than 28% of alcohol, and prohibiting the use of toxic denaturing agents). For example, the use of methanol in windshield wiper fluid was banned—although this ban was not always enforced, leading to poisoning deaths in homeless and other highly marginalized populations (Neufeld, Lachenmeier, Hausler, & Rehm, 2016). In sum, along with the tax increases, Russia successfully implemented a number of specific countermeasures against unrecorded alcohol use to ensure that the tax increases did not result in increases of unrecorded consumption; in fact, unrecorded consumption decreased (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2019).

Finland and other Nordic countries

Experience from Finland and other Nordic EU countries (for a summary, see also (Nelson & McNall, 2017)), where most unrecorded consumption stems from cross-border travellers’ imports (cross-border shopping), does not consistently find simple relationships of taxation increases leading to unrecorded consumption increases, or taxation decreases leading to unrecorded decreases (Karlsson, 2021; Mäkelä & Österberg, 2009). For instance, contrary to expectations, the Finnish tax cuts by one third in 2004 were associated with an increase in unrecorded consumption (Mäkelä & Österberg, 2009)—an indication that tax cuts as a means to reduce unrecorded consumption may not always be successful. The tax increases in Finland after 2004 were variously associated with increases, decreases, and no changes in unrecorded consumption (Karlsson, 2021). Similarly, alcohol-industry supported researchers (Nelson & McNall, 2017) found a mixed picture for the relationship between tax changes and unrecorded consumption in different case studies from Denmark, Finland and Sweden.

Kenya and Botswana (Sub-Saharan Africa)

Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the regions with high unrecorded consumption levels (Probst et al., 2019), where alcohol industry interests and others have argued that this situation makes the implementation of high levels of alcohol taxation futile (Ferreira-Borges et al., 2017). Indeed, partly for this reason, several African countries over the past decade actually reduced alcohol taxes (Ferreira-Borges et al., 2017; Jernigan & Babor, 2015).

Kenya has recently begun increasing its alcohol excise taxes (Kenya Revenue Authority, 2021) and, overall, the experience has been that alcohol tax increases have not resulted in substantial increases in either unrecorded consumption or decreases in government revenue (Ochieng’ & Agwaya, 2020). While it may be too early yet for a definitive evaluation of the most recent tax increase, especially in light of a lack of systematic monitoring of unrecorded alcohol, there are no signs that the levels of unrecorded alcohol consumption or of alcohol-attributable harms have increased. A key explanation for this outcome may be the existing high base rate of unrecorded alcohol use, a base rate which does not seem to change as a result of tax measures.

In general for sub-Saharan Africa, where the level of unrecorded alcohol is among the highest in the world (Probst et al., 2019), there is no consistent evidence that tax increases have led to either an increase in unrecorded or total alcohol consumption, or to an increase in alcohol-attributable harm. In Botswana, a levy on alcohol was introduced in several steps starting in 2008, which, at its peak, was 55% for beverages with more than 5% alcoholic strength. This levy was reduced to 35% after 10 years, as a result of pressure from the media and the alcohol industry (Morojele, Dumbili, Obot, & Parry, 2021). Recorded per capita consumption decreased by 27% between 2008 and 2016; unfortunately, there are no empirical trend data for unrecorded consumption in Botswana for the same period (Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis (BIDPA), 2017). There has been widespread belief that, as a result, unrecorded consumption, especially smuggling, would have increased for both home consumption as well as for resale. Botswana’s revenue agency noted that cases of underreporting had increased (with some economic operators declaring alcoholic beverages to be soft drinks in order to evade the levy), as well as a possible increase in smuggling activities, in part driven by the cheaper price of alcoholic beverages in South Africa (Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis (BIDPA), 2017). Even if unrecorded alcohol consumption did indeed increase, this increase would likely not have been equal to the decreases seen in recorded consumption, as evidenced by decreases in household expenditures for alcohol and tobacco, and reduced numbers of traffic collisions and fatalities (Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis (BIDPA), 2017; Sebego et al., 2014). Since the rates of traffic collisions and fatalities may also have been affected by other policy interventions, a causal attribution is difficult to make (Sebego et al., 2014). But overall, even if unrecorded consumption had increased as a result of the new taxation, the net effect on public health outcomes seems to have been largely positive.

Another lesson from Botswana is worth noting: the public discourse in Botswana failed to publicize and/or widely communicate the public health motives behind raising the taxes, which allowed critics to paint a false picture of arbitrary money-generating measures. Even when such tax measures are clearly proven to be successful to achieve public health goals, they will likely not be sustainable if the public and the media do not believe them to be necessary or successful in this respect.

Overall conclusions from the case studies

The case studies clearly indicate that tax increases do not automatically lead to an increase in unrecorded consumption. It depends on:

the level and price of unrecorded consumption in the particular society, and on the people who are currently consuming it or who may consider consuming it. There is, of course, a difference if consumption of unrecorded alcohol in a society is legal and/or socially widely accepted behaviour (e.g., cross-border shopping in the EU), or if it is a behaviour restricted to marginalized groups in specific situations (e.g., the drinking of windshield wiper fluid by homeless people with alcohol dependence in the Russian Federation (Neufeld et al., 2016)). To give another example: in Thailand, an increase in spirits taxation resulted in only slight increases in illegally distilled spirits, and only in communities where such distilling was common before the tax increase. The overall impact on unrecorded consumption was negligible (Chaiyasong et al., 2011).

the availability of unrecorded alcohol products for the people most affected (i.e., people of low income and education). If the only unrecorded alcohol available is via cross-border shopping, people of low income, living some distance from the border and likely without access to a vehicle, will not be buying or consuming this type of alcohol (Lhachimi, 2021).

the particular government’s countermeasures against unrecorded consumption when it increases excise taxes for recorded alcohol (see next point).

the presence of large-scale producers of certain types of unrecorded alcohol, and a legislative framework that leaves room for tax evasion and the production of counterfeit alcohol, surrogates, pseudo-surrogates (products officially declared as non-beverage alcohol but deliberately produced by the industry to appeal to heavy drinkers, e.g., fragrance-free colognes in Russia) and other products which are not taxed or regulated.

Thus, unrecorded alcohol consumption should be considered in the formulation of taxation policies, especially in countries where the proportion of this type of alcohol use is high. Taxation increases for alcoholic beverages have two main objectives: to increase revenue (potentially covering part of the economic costs of alcohol use to society (Manthey et al., 2021)), as well as to improve public health. Reviews have concluded that the goal to increase government revenue is usually realized (Chaloupka, Powell, & Warner, 2019; The Task Force on Fiscal Policy for Health, 2019; Wright, Smith, & Hellowell, 2017). For the latter goal, important public health indicators such as mortality, morbidity, or disability must be reduced following the intervention. In all of the case studies of tax increases presented here, the public health goals seem to have been realized. This corroborates the findings of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on this topic which have been conducted without industry financing (Wagenaar, Tobler, & Komro, 2010).

The available evidence does not suggest either that tax increases automatically lead to increases in unrecorded consumption, or that tax increases should be dismissed in situations where unrecorded consumption increases might be expected. Instead, as the example of Russia has shown, countermeasures can be applied to help ensure the success of taxation increases and prevent a potential shift to unrecorded consumption. The success of these countermeasures depends on the categories of unrecorded alcohol available in a particular country.

Countermeasures for unrecorded consumption

What policy options are available to reduce unrecorded alcohol consumption, and what is the evidence for each?

Previous reviews have identified some policy measures that can reduce the production and use of unrecorded alcohol ((Lachenmeier, 2009; Lachenmeier, Neufeld, & Rehm, 2021; Lachenmeier, Taylor, & Rehm, 2011); Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of alcohol policy measures suggested to reduce the production and use of unrecorded alcohol

| • Implementing actions which limit illegal trade and counterfeiting and take more control over the alcohol market, including the introduction of tax stamps, electronic surveillance systems, and increased enforcement against illegal activities (Lachenmeier, Neufeld, & Rehm, 2021; Lachenmeier, Taylor, et al., 2011). |

| • Integrating some types of the unrecorded alcohol supply, such as traditional alcoholic beverages, into the commercial sector (Thamarangsi, 2013; World Health Organization, 2010), e.g., by offering financial incentives to home and small-scale artisanal producers for registration and quality control or by establishing a government monopoly which buys their products or replaces them in the market (Lachenmeier & Rehm, 2010). Potential measures could also include providing alternative employment for those engaged in illegal alcohol production and distribution (Gururaj et al., 2021). |

| • Banning the sale to the general public of toxic compounds that could be admixed to alcohol (e.g., methanol) and prohibiting the use of toxic compounds to denature non-beverage alcohol. |

| • Reducing cross-border shopping by various means: limiting imports via quotas, narrowing the tax and price differences, eliminating tax-free sales, or enforcing stricter controls on sales of unrecorded alcohol in places where such shopping is limited or illegal. |

| • Lowering recorded alcohol prices to remove the economic incentive for buying unrecorded alcohol (but see text). |

Monitoring and surveillance systems

One of the broadest measures applied to limit unrecorded consumption is the establishment of a monitoring and surveillance system for alcohol, such as the Unified State Automated Information System (EGAIS) system, which has been described earlier in the Russian case study (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2019). Such systems—including but not limited to the use of proper tax stamps—allow for the detection of unrecorded alcohol in the distribution system and give customers some control over what they are buying. For tobacco, similar systems are already in place in many countries and regions and are considered to be standard practice. For instance, the EU Tobacco Products Directive 2014/40/EU and its implementation legislation have established the first regional tobacco tracking and tracing system to control the supply chain of tobacco products legally manufactured or imported on the EU’s internal market (eur-lex.europa.eu, 2021; European Commission, 2014). The success of a similar system adopted for alcohol in the Russian Federation points to the need for having an equivalent for alcohol at the EU level, which would also allow for more comprehensive monitoring and surveillance of cross-border alcohol trade between EU countries. The system could of course be manipulated, but any such efforts by members of organized crime would come at a cost, requiring them to purchase technology to evade it. And—as with almost all forms of alcohol control policy—much of the success of monitoring and surveillance systems will depend on the strength of enforcement (Babor et al., 2010; Babor et al., 2021). Monitoring and surveillance could also include tracking all cross-border transfers, as required for instance in the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs for opium and its derivatives (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2021). Finally, monitoring and surveillance could regularly test the quality of all alcohol products consumed, including unrecorded products, and the results distributed in rapid alert systems warning the public, for example when instances of methanol adulteration are detected (e.g., for the European Union: (European Commission, 2020).

Integration of unrecorded alcohol into the legal market, financial incentives, and government monopolies

The integration of some forms of unrecorded alcohol into the legal market has been suggested by WHO as part of their global strategy ((World Health Organization, 2010); see also (Thamarangsi, 2013)). We will mainly discuss home or small-scale artisanal production, which in some regions (e.g., in Africa) is often linked to traditional alcoholic beverages and income for women (Colson & Scudder, 1988; Limaye, Rutkow, Rimal, & Jernigan, 2014; Mkuu et al., 2019). In this case, because these women rely upon sales for subsistence, policies should be designed so as to avoid limiting women’s economic opportunities while protecting community health (Mkuu et al., 2019).

One of the more promising options may be to offer financial incentives to the producers of unrecorded alcohol to register the alcohol and engage in quality control activities. For instance, the government could establish a monopoly to buy unrecorded spirits at market prices and initiate quality control monitoring, as the German government did after World War I to limit unrecorded consumption ((Lachenmeier & Rehm, 2010); see also (Cahannes, 1981) for a similar rationale for establishing a monopoly in Switzerland). In this case, the spirits purchased by the government were then cleaned and converted into beverage or industrial alcohol.

The implications of a monopoly with this function in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) need to be considered carefully, with special attention paid to whether or not the revenues generated by a monopoly outweigh the cost to the government of running it. Of course, different functions may be integrated into such a monopoly (for general considerations, see (Kortteinen, 1989)). Alternatively, a process that increases recorded product share by offering cheaper recorded products with a more traditional content (e.g., maize or sorghum beer in Africa) might prove effective (see (Willis, 2003) for an example in Kenya; for sorghum, see (Adebo, 2020)). Recent globalization and economic growth have resulted in a decrease in traditional beverages and an increase in beer and other globalized beverages when the economic wealth of a country increases (e.g., see the changes concerning pulque versus industrial beer in Mexico (Medina-Mora, Villatoro, Caraveo, & Colmenares, 2000)).

Restricting the availability of toxic additives

As identified in the sections above, one major problem with unrecorded alcohol—apart from the alcohol itself—appears to be the addition of toxic compounds such as methanol, and potential contamination during production (especially in low- and lower-middle income countries, and countries where methanol is cheaper due to the higher prices and taxation of ethanol). Potential policy options therefore include restricting access to methanol (e.g., through higher taxation) (Mkuu et al., 2019), and requiring that any “denaturing” of nonbeverage alcohol be non-toxic. The outlined example of changes in denaturing agents in the Russian Federation, where methanol was forbidden, and a new list of strong-smelling denaturing agents was introduced, highlights how this issue can be managed. Still, methanol-based counterfeited technical fluids were still misused after the legislation changes as surrogate alcohol by the poorest community members, who seem to drink these fluids despite knowing the risks (Neufeld et al., 2016).

Most of the risks regarding the contamination of alcohol by methanol could be avoided by strictly enforced methanol monitoring or its prohibition in retail outlets. Especially in countries with higher proportions of surrogate alcohol consumption, measures mitigating methanol poisoning, including the strict enforcement of regulations for medicinal, cosmetic, and industrial alcohol, are needed (Lachenmeier, Neufeld, & Rehm, 2021; Lachenmeier, Taylor, et al., 2011). In Russia, the introduction of new obligatory additives for the denaturing of non-beverage alcohol in 2006 may have decreased unrecorded consumption, along with other important measures such as introducing new excise stamps and increasing tax on raw ethanol, which has eliminated the financial incentive to produce cheap surrogates (Nemtsov, Neufeld, & Rehm, 2019). Due to the difficulties in implementing policy measures against unrecorded alcohol and its contamination in Kenya and similar settings, the development of low-cost methanol detection systems has been suggested, to allow both producers and consumers the opportunity to avoid lethally contaminated alcohol (Carey, Kinney, Eckman, Nassar, & Mehta, 2015).

Cross-border sales

Cross-border sales are not a major problem from a global perspective, but constitute the main source of unrecorded alcohol in some regions, such as northern Europe (Rehm et al., 2014). The problem is complicated in this region by the fact that the EU considers alcohol to be an “ordinary” commodity, with almost no restrictions on cross-border trade (Babor et al., 2010). Two obvious solutions at the EU level could be to: (1) stipulate that alcohol is no ordinary economic commodity and impose limitations on cross-border trade, possibly by following the example of the Eurasian Economic Union with its Customs Code (which limits the duty-free import of alcoholic beverages to only three litres of any product per person (Eurasian Economic Commission, 2017)); or (2) harmonize taxation (for instance, by increasing minimal taxation for all EU-member states).

Another solution would be to institute bilateral or multilateral harmonization of taxes by the neighbouring countries affected. For instance, the current provisions of the Eurasian Economic Union require a harmonization process of excise rates on alcohol and tobacco products across all the Member States (Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and the Russian Federation) every five years to ensure that alcohol prices remain somewhat similar and to prevent cross-border issues (Board of the Eurasian Economic Commission, 2018). Taxation does not need to be at exactly the same level, however, since the real costs for cross-border trading include the costs associated with crossing the border, including gasoline (Lhachimi, 2021).

Taxation

The last “solution” in the list involves lowering taxes to make recorded (tax-paid) alternatives more attractive and thereby lower unrecorded consumption. However, it must be emphasized that in this case, the overall harm caused by alcohol (recorded and not) is not likely to change and might even increase, because recorded consumption will likely and total consumption may possibly increase because of higher overall affordability of alcohol. In addition, empirically, lowering of taxation did not lead to lower unrecorded consumption in several of the examples.

Unintended consequences of policy measures to reduce unrecorded alcohol consumption Since the level of ethanol use has been identified as the best indicator for alcohol-attributable harm (and its reduction is one of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (Rehm, Casswell, Manthey, Room, & Shield, 2020; Rehm, Crépault, et al., 2020)), alcohol policies should avoid the imposition of “solutions” for unrecorded consumption which, in fact, ultimately result in an increase in overall consumption.

For example, in Belarus, the introduction in 1997 of a new cheap alternative alcohol in the form of fortified fruit wines, combined with increased penalties for homebrewing, contributed to the reduction in, and in more recent years, the almost complete eradication of, home production of alcohol, which in the 1990s had made up a significant share of unrecorded alcohol. The total alcohol consumption in the population of Belarus, however, actually grew rapidly over the same time period, along with cases of liver cirrhosis and overall mortality, due in part to the consumption of cheap fruit wines (Grigoriev & Bobrova, 2020).

Nevertheless, and with little evidence to back their claims, the large global alcohol producers typically suggest targeting unrecorded alcohol alone in order to reduce alcohol problems (International Alliance for Responsible Drinking (IARD), 2017). For example, arguments that illicit production may result in toxic consequences such as methanol poisoning may be used as evidence that taxes on the licit production should be limited, ignoring the orders-of-magnitude difference between the number of methanol poisonings per year and the morbidity and mortality associated with ethanol itself.

The industry also uses political pressure to gain advantage by suppressing unrecorded alcohol from any non-commercial sources. Arguments against illegal production have often included referring to the “loss of billions of dollars in government revenues” due to transnational criminal networks illicitly trading in alcohol (Skehan et al., 2016). Moreover, the presence of unrecorded alcoholic products and various illegal and semi-legal alcohol markets in a country like Russia is often used as an argument to lower alcohol taxes and loosen alcohol policy in general, instead of making a stronger case for enforcement and anti-corruption measures (Platforma, 2019). However, while some ingredients in some unrecorded alcohol may pose a health risk over and above the risk of ethanol, the major public health threat is clearly related to the ethanol itself (Casswell et al., 2016; Rehm et al., 2014). As such, any measure against unrecorded consumption should be weighed against the overall impact on health if it could potentially result in increasing overall alcohol consumption.

A case study of unrecorded alcohol use in East Africa has also stressed the importance of considering the unintended consequences of policies on unrecorded alcohol regarding issues of gender, empowerment of women, and economic opportunities for women, since women tend to comprise the majority of those making homebrew in this region (GS Uganda, 2018; Mkuu et al., 2019; Schmidt & Room, 2012). Another unintended consequence of the disruption of the making of traditional beers or homebrewing, particularly in African countries, involves industry moving in and competing with lower prices—leading to a paradoxical situation of increased per capita consumption (Allen & Glenn, 2020).

Conclusion

Consumption of unrecorded alcohol makes up a sizable and stable part of alcohol consumption. While potential increases of unrecorded consumption should be considered in situations where there are substantial increases in alcohol taxation, unrecorded consumption does not constitute a principal barrier for such increases. Empirical evidence demonstrated that taxation increases were in fact associated with varied trends of unrecorded consumption, including decreases in some cases. Our review of the evidence further demonstrated that even in instances where consumption of unrecorded alcohol was expected to increase because of previously high levels and a large proportion of the population engaging in drinking it, there are effective countermeasures which governments can and should use. Such countermeasures against unrecorded consumption for any particular country will depend on its unique characteristics in terms of the type of unrecorded consumption, drinking culture, and policy environment.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Kim Bloomfield for providing information on unrecorded consumption in Denmark; Thomas Karlsson for his insights into the dynamics of unrecorded consumption in Finland; Carolin Kilian, who commented on a more comprehensive review paper for the EU; and Neo Morojele, who provided information for the case study on Botswana. Astrid Otto is thanked for referencing and copy-editing the manuscript.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, specifically from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) [grant number 1R01AA028224], and by the Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency (CHAFEA), acting under a mandate from the European Commission (EC), specifically by the AlHaMBRA project (EU Health Programme 2014–2020 under a service contract 2019 71 05).

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors only, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the EC, CHAFEA, the NIH, or the World Health Organization, for which MN is a consultant.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adebo OA (2020). African sorghum-based fermented foods: past, current and future prospects. Nutrients, 12(4), 1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adelekan M. (2008). Noncommercial alcohol in sub-saharan Africa. In ICAP Review 3. Noncommercial alcohol in three regions (pp. 3–15). Washington, DC: International Center for Alcohol Policies. [Google Scholar]

- Allen B, & Glenn J. (2020). Community Level Perspectives on Informal Alcohol: Understanding the Role of Traditional Brewers in Dowa District, Malawi. (Undergraduate Honors Theses). Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. (109) [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Caetano R, Casswell S, Edwards G, Giesbrecht N, Graham K, . . . Rossow I. (2010). Alcohol: No ordinary commodity. Research and public policy (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Casswell S, Graham K, Huckle T, Livingston M, Österberg E, . . . Sornpaisarn B. (2021). Alcohol: No ordinary commodity. Research and public policy (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Board of the Eurasian Economic Commission. (2018). On draft agreements on the principles of tax policy excise duties on alcohol and tobacco products in Member States of the Eurasian Economic Union. Retrieved from https://www.alta.ru/tamdoc/18r00184/

- Bobrova N, West R, Malutina D, Koshkina E, Terkulov R, & Bobak M. (2009). Drinking alcohol surrogates among clients of an alcohol-misuser treatment clinic in Novosibirsk, Russia. Subst Use Misuse, 44(13), 1821–1832. doi: 10.3109/10826080802490717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis (BIDPA). (2017). Final Report: A Study To Evaluate The National Interventions Against Alcohol Abuse In Botswana. Gaborone, Botswana: BIDPA. [Google Scholar]

- Bujdosó O, Pál L, Nagy A, Árnyas E, Ádány R, Sándor J, . . . Szűcs S. (2019). Is there any difference between the health risk from consumption of recorded and unrecorded spirits [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- containing alcohols other than ethanol? A population-based comparative risk assessment. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 106, 334–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahannes M. (1981). Swiss alcohol policy: the emergence of a compromise. Contemp. Drug Probs, 10, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Carey K, Kinney J, Eckman M, Nassar A, & Mehta K. (2015). Chang’aa culture and process: detecting contamination in a killer brew. Procedia Engineering, 107, 395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Casswell S, Callinan S, Chaiyasong S, Cuong PV, Kazantseva E, Bayandorj T, . . . Wall M. (2016). How the alcohol industry relies on harmful use of alcohol and works to protect its profits. Drug and Alcohol Review, 35(6), 661–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiyasong S, Limwattananon S, Limwattananon C, Thamarangsi T, Tangchareonsathien V, & Schommer J. (2011). Impacts of excise tax raise on illegal and total alcohol consumption: A Thai experience. Drugs: education, prevention and policy, 18(2), 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chaloupka FJ, Powell LM, & Warner KE (2019). The use of excise taxes to reduce tobacco, alcohol, and sugary beverage consumption. Annual review of public health, 40, 187–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm D, Moro D, Bertram M, Pretorius C, Gmel G, Shield KD, & Rehm J. (2018). Are the “Best Buys” for Alcohol Control Still Valid? An Update on the Comparative Cost-Effectiveness of Alcohol Control Strategies at the Global Level. J Stud Alcohol Drugs, 79(4), 514–522. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30079865 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colson E, & Scudder T. (1988). For prayer and profit: The ritual, economic, and social importance of beer in Gwembe District, Zambia, 1950–1982. Stanford, U.S.A.: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drug Tobacco and Alcohol Control Department. (2013). Evaluation of illegal alcohol sales in Lithuania. 2013 [Study in Lithuanian: NEAPSKAITYTOS ALKOHOLIO APYVARTOS LIETUVOJE ĮVERTINIMAS METODIKA]. Retrieved from http://old.ntakd.lt/files/Apklausos_ir_tyrimai/neleg_met.pdf

- Erickson RA, Stockwell T, Pauly B, Chow C, Roemer A, Zhao J, . . . Wettlaufer A. (2018). How do people with homelessness and alcohol dependence cope when alcohol is unaffordable? A comparison of residents of Canadian managed alcohol programs and locally recruited controls. Drug and Alcohol Review, 37, S174–S183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estonian Institute of Economic Research. (2005). Consumption and trade of illegal alcohol in Estonia. Tallinn, Estonia: Estonian Institute of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- eur-lex.europa.eu. (2021). COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2018/574 of 15 December 2017 on technical standards for the establishment and operation of a traceability system for tobacco products (Text with EEA relevance). Retrieved from https://eurlex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018R0574&from=GA

- Eurasian Economic Commission. (2017). Treaty on the Customs Code of the Eurasian Economic Union. Retrieved from https://docs.eaeunion.org/docs/ru-ru/01413569/itia_12042017 [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (2014). Directive 2014/40/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 3 April 2014 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products and repealing Directive 2001/37/EC Off J Eur Union, 127, 1–38. Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014L0040&from=en [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (2020). Protecting European Consumers: follow-up action on dangerous product alerts increased significantly in 2019. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_1270

- Ferreira-Borges C, Parry CDH, & Babor TF (2017). Harmful use of alcohol: a shadow over subSaharan Africa in need of workable solutions. International journal of environmental research and public health, 14(4), 346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamburd MR (2008). Breaking the ashes: The culture of illicit liquor in Sri Lanka. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriev P, & Bobrova A. (2020). Alcohol control policies and mortality trends in Belarus. Drug and Alcohol Review, 39(7), 805–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GS Uganda. (2018). Alcohol Brewing in Jinja: A Death Trap for Women in Poverty (VIDEO). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wPlGFxmIr84

- Gururaj G, Gautham MS, & Arvind BA (2021). Alcohol consumption in India: A rising burden and a fractured response. Drug and Alcohol Review, 40(3), 368–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Research Institute. (2018). Estimates of unrecorded alcohol in Lithuania in 2016–2017 [Neapskaityto alkoholio suvartojimo Lietuvoje įvertinimas 2016–2017 m.]. (20/12/2018). A report for the Department of Drug Tobacco and Alcohol Control. Retrieved from https://ntakd.lrv.lt/uploads/ntakd/documents/files/Neapskaitytos%20alkoholio%20apyvartos%20vertinimas%202018_12_20%20(galutinis).pdf

- Il’ina IJ (2018). Roznichnaja prodazha i internet-prodazhe nesovershennoletnim alkogol’noj produkcii-surrogata alkogolja [Retail sale and online sale to minors of alcoholic products-surrogate alcohol]. Aktual’nye problemy bor’by s prestuplenijami i inymi pravonarushenijami: materialy shestnadcatoj mezhdunarodnoj nauchno-prakticheskoj konferencii/pod red. JuV Anohina.-Barnaul: Barnaul’skij juridicheskij institut MVD Rossii, 1, 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- International Alliance for Responsible Drinking (IARD). (2017). Policy Review: Unrecorded Alcohol. Retrieved from http://iardwebprod.azurewebsites.net/getattachment/d76b085b-6a26-4080-b846-ca5df14e301e/pr-unrecorded.pdf

- International Alliance for Responsible Drinking (IARD). (2018). Policy Review In Brief: Taxation of Beverage Alcohol. Retrieved from http://iardwebprod.azurewebsites.net/getattachment/660ef449-ce90-414e-8064-3891487581c2/iard-policy-review-taxation-of-beverage-alcohol.pdf

- Jernigan DH (1999). Country profile on alcohol in Zimbabwe. In Riley L. & Marshall M. (Eds.), Alcohol and public health in eight developing countries (pp. 157–175). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization,. [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan DH, & Babor TF (2015). The concentration of the global alcohol industry and its penetration in the A frican region. Addiction, 110(4), 551–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson T. (2021, 16/04/2021). [Alcohol taxation and unrecorded alcohol in Finland 2004 – 2020 (personal communication)]. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya Revenue Authority. (2021). Sin Tax (Blog 24/04/2020). Retrieved from https://www.kra.go.ke/en/media-center/blog/823-sin-tax

- Khaltourina D, & Korotayev A. (2015). Effects of Specific Alcohol Control Policy Measures on AlcoholRelated Mortality in Russia from 1998 to 2013. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 50(5), 588–601. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agv042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortteinen T. (1989). State monopoly systems and alcohol prevention in developing countries: Report on a collaborative international study. British journal of addiction, 84(4), 413–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotelnikova Z. (2017). Explaining counterfeit alcohol purchases in Russia. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 41(4), 810–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachenmeier DW (2009). Reducing harm from alcohol: what about unrecorded products? The Lancet, 374(9694), 977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachenmeier DW, Gmel G, & Rehm J. (2013). Unrecorded alcohol consumption. In Boyle P, Boffetta P, Lowenfels AB, Burns H, Brawley O, Zatonski W, & Rehm J. (Eds.), Alcohol: Science, Policy, and Public Health (pp. 132–142). Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lachenmeier DW, Leitz J, Schoeberl K, Kuballa T, Straub I, & Rehm J. (2011). Quality of illegally and informally produced alcohol in Europe: Results from the AMPHORA project. Adicciones, 23(2), 133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachenmeier DW, Monakhova YB, Markova M, Kuballa T, & Rehm J. (2013). What happens if people start drinking mouthwash as surrogate alcohol? A quantitative risk assessment. Food and chemical toxicology, 51, 173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachenmeier DW, Neufeld M, Kilian C, Room R, Sornpaisarn B, Štelemėkas M, . . . Rehm J. (2021). The health impact of unrecorded alcohol use and its policy implications. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Lachenmeier DW, Neufeld M, & Rehm J. (2021). The Impact of Unrecorded Alcohol Use on Health: What Do We Know in 2020? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 82(1), 28–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachenmeier DW, & Rehm J. (2010). Von Schwarzbrennern und Vieltrinkern. Die Auswirkungen des deutschen Branntweinmonopols auf den gesundheitlichen Verbraucherschutz. (Bootleggers and heavy drinkers. The impact of the German alcohol monopoly on public health and consumer safety). 56, 91–93. [Google Scholar]

- Lachenmeier DW, Taylor BJ, & Rehm J. (2011). Alcohol under the radar: do we have policy options regarding unrecorded alcohol? International Journal of Drug Policy, 22(2), 153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachenmeier DW, & Walch SG (2018). Commentary on Probst et al.(2018): Unrecorded alcohol use—an underestimated global phenomenon. Addiction, 113(7), 1242–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachenmeier DW, Walch SG, & Rehm J. (2019). Exaggeration of health risk of congener alcohols in unrecorded alcohol: does this mislead alcohol policy efforts? Regulatory toxicology and pharmacology: RTP, 107, 104432–104432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang K, & Ringamets I. (2018). Unrecorded Alcohol in the Baltic States: Summary Report. Retrieved from http://iardwebprod.azurewebsites.net/getattachment/36c0ecba-1ae2-4d53-9b9a97cd9c0357b3/sura-baltics-summary-report.pdf

- Lang K, Väli M, Szűcs S, Ádány R, & McKee M. (2006). The composition of surrogate and illegal alcohol products in Estonia. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 41(4), 446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lhachimi SK (2021). Revisiting the Swedish alcohol stasis after changes in travelers’ allowances in 2004: petrol prices provide a piece of the puzzle. Eur J Health Econ, 22(2), 187–193. doi: 10.1007/s10198-020-01237-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limaye RJ, Rutkow L, Rimal RN, & Jernigan DH (2014). Informal alcohol in Malawi: stakeholder perceptions and policy recommendations. Journal of public health policy, 35(1), 119–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lithuanian Tobacco and Alcohol Control Coalition. (2020). An Appeal of the NGOs to the Lithuanian Government and Parliament To Maintain Current Alcohol Control Policies [Lietuvos nevyriausybinės organizacijos kreipėsi į LRV ir Seimą dėl alkoholio kontrolės politikos tęstinumo]. Retrieved from https://www.ntakk.lt/lietuvos-nevyriausybines-organizacijos-kreipesii-lrv-ir-seima-del-alkoholio-kontroles-politikos-testinumo/

- Liyanage U. (2008). Noncommercial alcohol in southern Asia: The case of kasippu in Sri Lanka. In Noncommercial alcohol in three regions (pp. 24–34). Washington, DC: International Center for Alcohol Policies. [Google Scholar]

- English LRT. (2019, 08/16/2019). Baltic booze wars: cuts and hikes of alcohol duties bring limited results. Retrieved from https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1088324/baltic-booze-wars-cuts-and-hikes-of-alcohol-duties-bring-limited-results

- Mäkelä P, & Österberg E. (2009). Weakening of one more alcohol control pillar: a review of the effects of the alcohol tax cuts in Finland in 2004. Addiction, 104(4), 554–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthey J, Hassan SA, Carr S, Kilian C, Kuitunen-Paul S, & Rehm J. (2021). What are the economic costs to society attributable to alcohol use? A systematic review and modelling study. PharmacoEconomics, doi: 10.1007/s40273-40021-01031-40278 [PMID: 33970445]. doi:doi: PMID: 33970445] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthey J, Shield KD, Rylett M, Hasan OSM, Probst C, & Rehm J. (2019). Global alcohol exposure between 1990 and 2017 and forecasts until 2030: a modelling study. The Lancet, 393(10190), 2493–2502. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32744-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall M. (1996). Rural brewing, exclusion, and development policy-making. Gender & Development, 4(3), 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Mora ME, Villatoro J, Caraveo J, & Colmenares E. (2000). Mexico. In Demers A, Room R, & Bourgault C. (Eds.), Surveys of drinking patterns and problems in seven developing countries (pp. 13–32). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization,. [Google Scholar]

- Mkuu RS, Barry AE, Swahn MH, & Nafukho F. (2019). Unrecorded alcohol in East Africa: A case study of Kenya. International Journal of Drug Policy, 63, 12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morojele NK, Dumbili EW, Obot IS, & Parry CD (2021). Alcohol consumption, harms and policy developments in sub-Saharan Africa: The case for stronger national and regional responses. Drug and Alcohol Review, 40(3), 402–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JP, & McNall AD (2016). Alcohol prices, taxes, and alcohol-related harms: A critical review of natural experiments in alcohol policy for nine countries. Health Policy, 120(3), 264–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JP, & McNall AD (2017). What happens to drinking when alcohol policy changes? A review of five natural experiments for alcohol taxes, prices, and availability. The European Journal of Health Economics, 18(4), 417–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemtsov AV (2011). A Contemporary History of Alcohol in Russia. Stockholm, Sweden: Södertörns högskola. [Google Scholar]

- Nemtsov AV, Neufeld M, & Rehm J. (2019). Are trends in alcohol consumption and cause-specific mortality in Russia between 1990 and 2017 the result of alcohol policy measures? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 80(5), 489–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld M, Bunova A, Gornyi B, Ferreira-Borges C, Gerber A, Khaltourina D, . . . Rehm, J. (2020). Russia’s National Concept to Reduce Alcohol Abuse and Alcohol-Dependence in the Population 2010–2020: Which Policy Targets Have Been Achieved? International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(21), 8270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld M, Lachenmeier DW, Hausler T, & Rehm J. (2016). Surrogate alcohol containing methanol, social deprivation and public health in Novosibirsk, Russia. International Journal of Drug Policy, 37, 107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld M, Lachenmeier DW, Walch SG, & Rehm J. (2017). The internet trade of counterfeit spirits in Russia–an emerging problem undermining alcohol, public health and youth protection poli-cies? F1000Research, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld M, & Rehm J. (2018). Effectiveness of policy changes to reduce harm from unrecorded alcohol in Russia between 2005 and now. Int J Drug Policy, 51, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld M, Wittchen H-U, & Rehm J. (2017). Drinking patterns and harm of unrecorded alcohol in Russia: a qualitative interview study. Addiction Research & Theory, 25(4), 310–317. [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld M, Wittchen HU, Ross LE, Ferreira-Borges C, & Rehm J. (2019). Perception of alcohol policies by consumers of unrecorded alcohol - an exploratory qualitative interview study with patients of alcohol treatment facilities in Russia. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy, 14(1), 53. doi: 10.1186/s13011-019-0234-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochieng’ J, & Agwaya R. (2020). Excise taxation in Kenya: a situation analysis. Nairobi, Kenya: Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Okaru AO, Rehm J, Sommerfeld K, Kuballa T, Walch SG, & Lachenmeier DW (2019). The Threat to Quality of Alcoholic Beverages by Unrecorded Consumption. Volume 7: The Science of Beverages. In Alcoholic Beverages (pp. 1–34). Cambridge, MA: Woodhead Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pál L, Arnyas EM, Tóth B, Adám B, Rácz G, Adány R, . . . Szűcs, S. (2013). Consumption of home-made spirits is one of the main source of exposure to higher alcohols and there may be a link to immunotoxicity. Immunopharmacology and immunotoxicology, 35(5), 627–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pärna K. (2020). Alcohol consumption and alcohol policy in Estonia 2000–2017 in the context of Baltic and Nordic countries. Drug and Alcohol Review, 39(7), 797–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pärna K, Lang K, Raju K, Väli M, & McKee M. (2007). A rapid situation assessment of the market for surrogate and illegal alcohols in Tallinn, Estonia. Int J Public Health, 52(6), 402–410. doi: 10.1007/s00038-007-6112-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platforma. (2019). Tenevoj rynok alkogol’noj produkcii: struktura, tendencii, posledstvija. Rasshirennaja versija [The shadow market for alcoholic beverages: structure, trends, consequences. Extended version]. Center for the Development of the Consumer Market of the Moscow School of Management SKOLKOVO and the Center for Social Design “Platforma.”. Retrieved from http://rn-l.ru/normdocs/2019/2019-09-20-skolkovo-ten-alco-rynok.pdf

- Poznyak V, Fleischmann A, Rekve D, Rylett M, Rehm J, & Gmel G. (2013). The World Health Organization’s global monitoring system on alcohol and health. Alcohol research: current reviews, 35(2), 244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst C, Fleischmann A, Gmel G, Poznyak V, Rekve D, Riley L, . . . Rehm J. (2019). The global proportion and volume of unrecorded alcohol in 2015. Journal of Global Health, 9(1). doi: 10.7189/jogh.09.010421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst C, Manthey J, Merey A, Rylett M, & Rehm J. (2018). Unrecorded alcohol use: a global modelling study based on nominal group assessments and survey data. Addiction, 113(7), 1231–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radaev VA (2017). A Crooked Mirror: The Evolution of Illegal Alcohol Markets in Russia since the Late Socialist Period. In D. M. Beckert J. (Ed.), The architecture of illegal markets: Towards an economic sociology of illegality in the economy (pp. 218–241). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Casswell S, Manthey J, Room R, & Shield K. (2020). Reducing the Harmful Use of Alcohol: Have International Targets Been Met? European Journal of Risk Regulation, doi: 10.1017/err.2020.1084. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Crépault JF, Wettlaufer A, Manthey J, & Shield K. (2020). What is the best indicator of the harmful use of alcohol? A narrative review. Drug and Alcohol Review, 39(6), 624–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, & Imtiaz S. (2016). A narrative review of alcohol consumption as a risk factor for global burden of disease. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 11(1), 37. doi: 10.1186/s13011-016-0081-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Kailasapillai S, Larsen E, Rehm MX, Samokhvalov AV, Shield KD, . . . Lachenmeier DW (2014). A systematic review of the epidemiology of unrecorded alcohol consumption and the chemical composition of unrecorded alcohol. Addiction, 109(6), 880–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Kanteres F, & Lachenmeier DW (2010). Unrecorded consumption, quality of alcohol and health consequences. Drug and Alcohol Review, 29(4), 426–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Larsen E, Lewis-Laietmark C, Gheorghe P, Poznyak V, Rekve D, & Fleischmann A. (2016). Estimation of unrecorded alcohol consumption in low-, middle-, and high-income economies for 2010. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40(6), 1283–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, & Poznyak V. (2015). On monitoring unrecorded alcohol consumption. Alcoholism and Drug Addiction, 28(2), 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Bloomfield K, Gmel G, Grittner U, Gustafsson N-K, Mäkelä P, . . . Wicki M. (2013). What happened to alcohol consumption and problems in the Nordic countries when alcohol taxes were decreased and borders opened? The International Journal of Alcohol and Drug Research, 2(1), 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Jernigan DH, Carlini BH, Gmel G, Gureje O, Mäkela K, . . . Shield KD (2013). El alcohol y los países en desarrollo: una perspectiva de salud pública. Washington, Mexico: Organización Panamericana de la Salud & Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA, & Room R. (2012). Alcohol and inequity in the process of development: Contributions from ethnographic research. The International Journal of Alcohol and Drug Research, 1(1), 4155. [Google Scholar]

- Sebego M, Naumann RB, Rudd RA, Voetsch K, Dellinger AM, & Ndlovu C. (2014). The impact of alcohol and road traffic policies on crash rates in Botswana, 2004–2011: a time-series analysis. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 70, 33–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skehan P, Sanchez I, & Hastings L. (2016). The size, impacts and drivers of illicit trade in alcohol. In OECD (Ed.), Illicit Trade: Converging Criminal Networks (pp. pp. 217–240). Paris, France: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sornpaisarn B, Shield KD, Österberg E, & Rehm J. (2017). Resource tool on alcohol taxation and pricing policies. Geneva: World Health Organization and others. [Google Scholar]

- Štelemėkas M, Manthey J, Badaras R, Casswell S, Ferreira-Borges C, Kalediene R, . . . Rehm J. (2021). Alcohol control policy measures and all-cause mortality in Lithuania: an interrupted time-series analysis. Addiction, doi: 10.1111/add.15470. doi: 10.1111/add.15470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thamarangsi T. (2013). Unrecorded alcohol: significant neglected challenges. Addiction, 108(12), 2048–2050. doi: 10.1111/add.12300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Task Force on Fiscal Policy for Health. (2019). Health Taxes to Save Lives: Employing Effective Excise Taxes on Tobacco, Alcohol, and Sugary Beverages. Chairs: Michael R. Bloomberg and Lawrence H. Summers. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.org/program/public-health/taskforce-fiscal-policy-health/

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2021). Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/treaties/single-convention.html?ref=menuside

- Wagenaar AC, Tobler AL, & Komro KA (2010). Effects of alcohol tax and price policies on morbidity and mortality: a systematic review. American journal of public health, 100(11), 2270–2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis J. (2003). New generation drinking: the uncertain boundaries of criminal enterprise in modern Kenya. African Affairs, 102(407), 241–260. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2004). Global status report on alcohol Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2010). Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/activities/gsrhua/en/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2011). Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2014). Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2017). Tackling NCDs: “Best buys” and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259232/WHO-NMH-NVI-17.9-eng.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2018). Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/en/

- World Health Organization. (2021). World Health Statistics 2021: monitoring health for the SDGs sustainable development goals. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. (2019). Alcohol Policy Impact Case Study. The effects of alcohol control measures on mortality and life expectancy in the Russian Federation. Retrieved from http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/alcoholuse/publications/2019/alcohol-policy-impact-case-study-the-effects-of-alcohol-control-measureson-mortality-and-life-expectancy-in-the-russian-federation-2019

- Wright A, Smith KE, & Hellowell M. (2017). Policy lessons from health taxes: a systematic review of empirical studies. BMC public health, 17(1), 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]