Abstract

BACKGROUND

Parental incarceration impacts millions of children in the United States and has important consequences for youth’s adjustment and school-based outcomes.

METHODS

Using data from a survey of youth behavior in one large Midwestern state, we examined the effect of both present and past parental incarceration on school-based outcomes, across 3 school settings (public schools, alternative learning centers, and juvenile correctional facilities).

RESULTS

Parental incarceration was significantly associated with students’ poor school-based outcomes; however, these effects varied markedly by school setting. Among youth in public schools, parental incarceration was consistently associated with poor school outcomes. There were mixed effects among youth in alternative learning centers and no significant effects among youth in juvenile correctional facilities.

CONCLUSIONS

The study adds to a body of literature demonstrating the negative effects of parental incarceration on youth’s school-based outcomes for youth in public schools; however, findings were mixed for youth in alternative learning centers and juvenile correctional facilities. Implications for future research and school practitioners are discussed.

Keywords: parental incarceration, school outcomes, school outcomes, student engagement

There are about 2.7 million children who have a parent currently incarcerated in the United States (US),1 and millions more have experienced the incarceration of a parent in the past. Some estimates suggest that as many as one in 10 US children have a currently or formerly incarcerated parent2 and a growing body of literature highlights the considerable risk that these children often experience.3

Children with incarcerated parents are at an increased risk for physical health problems,4,5 and mental health problems such as internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (see Eddy and Poehlmann3 for a review). These problems may interfere with youth’s adjustment at home and school, and ultimately compromise their academic performance and school outcomes. In this paper, we use a large, representative sample to examine parental incarceration as a risk factor for youth’s school-based outcomes.

Parental Incarceration and Youth’s School Outcomes

The impact of parental incarceration on children’s outcomes at school is particularly important to consider, given the long-lasting implications of school success for adult adjustment across a variety of domains, including employment, physical health, substance use, incarceration.6–9 Previous research has examined associations between parental incarceration and a variety of school-based indicators, including grades,10,11 test scores,12 qualification for educational services,13 and academic performance.14 In addition, parental incarceration has been examined as a risk factor for poor health outcomes in young people.15

Several studies have found that parental incarceration is a risk factor for children’s academic and school-based outcomes. For example, Turney and Haskins16 found that elementary school children with incarcerated fathers were more likely to experience grade retention than their peers who had not experienced paternal incarceration. In their sample of children currently affected by their mother’s incarceration, Hanlon et al17 found that 49% of children aged 9 to 14 experienced behavioral problems at school, which led to their suspension, and 45% expressed little or no interest in school. Trice and Brewster18 examined school performance among adolescents (13 to 20 years old) with currently incarcerated mothers and found that when compared to the their best friends, adolescents with an incarcerated mother were more likely to be suspended, fail classes, drop out of school, and have extended absences from school. Using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, Huynh-Hohnbaum et al19 found that compared to children with no history of parental incarceration, those who had a mother and/or father incarcerated were less likely to obtain a high school diploma and chronicity of parental incarceration was negatively associated with youth’s likelihood of obtaining their diploma.

There are a number of potential reasons for the associations between parental incarceration and lower school performance. First, children of incarcerated parents regularly experience significant adverse circumstances that are risk factors for poor educational, behavioral, and psychosocial outcomes, such as economic disadvantage, residential instability, disruptions in caregiving, and chronic stress.20 The families of incarcerated persons also face significant shame and stigma,10 which could compromise emotional, behavioral, and academic functioning in children with incarcerated parents.

Yet, parental incarceration has not consistently been found to be a risk factor for children’s poor academic outcomes across the literature. For example, Cho found that maternal incarceration was not a risk factor for grade retention21 or low reading and math standardized test scores.22 In their meta-analysis, Murray et al20 concluded that parental incarceration was associated with increased risk for children’s antisocial behavior, but found no consistent effect for poor educational performance.

Differences by School Setting

One limitation of previous research in this area is a failure to consider school setting as it relates to academic outcomes and youth’s history of parental incarceration. For example, the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health is nationally representative sample and includes students attending a variety of school settings. Yet, in their study using this data set, Huynh-Hohnbaum et al19 did not test for potential variations by school setting in the associations between parental incarceration and academic outcomes. Some of the factors that precipitate youth’s removal from mainstream public schools into alternative school settings – such as school disengagement, academic failure, and truancy – may also be related to their experiences with parental incarceration. Further, the systemic disparities by race and economic status across different school settings parallel those seen in the adult criminal justice system. Youth who are referred to and attend alternative school settings – and adults in prison – are more likely to be poor, African American, and male.23,24 As such, youth’s experiences with parental incarceration and the effect this experience has on their school-based outcomes may vary considerably by school setting and is therefore an important area for future inquiry.

Study Aim and Hypotheses

In the current study, we consider parental incarceration as a risk factor for youth’s school-related outcomes across 3 school settings, namely mainstream public schools, alternative learning centers, and juvenile correctional facilities. On the basis of previous research, we expect that youth with a currently or formerly incarcerated parent will have worse school outcomes compared to their peers with no history of parental incarceration. Further, we expect that youth who are currently experiencing the incarceration of a parent will have significantly worse school-based outcomes than their peers who have experienced a parent’s incarceration in the past. We expect that these associations will hold accounting for key covariates and that these results will be consistent across school settings.

METHODS

Instrumentation

Data were drawn from the 2013 Minnesota Student Survey, a statewide survey of youth behavior. The survey was administered to 5th, 8th, 9th, and 11th grade students in public schools and all students in alternative learning centers and juvenile correctional facilities during the 2012–2013 school year. Fifth grade public school students received a shorter version of the survey, which did not contain items addressing parental incarceration or other topics deemed inappropriate for this age group, including items about drug use and sexual behavior. As such, data from 5th grade students were excluded from the current study.

Participants

In total, 124,542 youth were surveyed across the 3 school settings. Students attending 452 mainstream public schools, 58 alternative learning centers, and 20 juvenile correctional facilities were surveyed. Out of the 334 public school districts in the study state, 280 (84%) agreed to participate. Comparable information was not available for alternative learning centers and juvenile correctional facilities. Unlike mainstream public schools in the study state, alternative learning centers are designed for students who are at-risk for educational failure.25 These schools are characterized by smaller class sizes and an experiential approach to learning, with a focus on vocational and career skills. Classroom instruction is designed to meet students’ individual learning styles, as well as their social and emotional needs. The juvenile correctional facilities in the study state included both secure (locked) and non-secure facilities. Youth in juvenile correctional facilities have been adjudicated delinquent and court-ordered to correctional placement by a judge, have been deemed to be a risk to themselves or others, did not appear for court, or did not stay in the lawful custody of the person to whom they were released.26 Under state statute, these facilities provide education for youth in custody, including opportunities to earn high school credits, classes taught by local school teachers, and general education development readiness programs.

Age, sex, race/ethnicity, poverty, and individualized education plan/special education were included as covariates in all multivariable analyses. Due to the small cell sizes for several racial and ethnic groups, the race/ethnicity variable was dichotomized (white non-Hispanic = 0, all other races/ethnicities = 1). Youth were considered to be living in poverty if they endorsed any one of the following 3 items: (1) “Do you currently get free or reduced-price lunch at school?” (2) “During the last 30 days, have you had to skip meals because your family did not have enough money to buy food?” and (3) “During the past 12 months, have you stayed in a shelter, somewhere not intended as a place to live, or someone else’s home because you had no other place to stay?” Descriptive statistics for study participants, by school setting, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics by School Setting

| Public Schools | Alternative Learning Centers | Juvenile Correctional Facilities | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 112,787 | N = 1720 | N = 321 | |

| Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Age, M(SD) | 14.87(1.34) | 16.80(1.29) | 15.96(1.31) |

| Male | 49.3% | 52.5% | 72.9% |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| American Indian | 1.1% | 4.7% | 14.3% |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 5.3% | 3.3% | 1.6% |

| Black | 4.5% | 8.4% | 17.4% |

| Multiple Races | 6.6% | 12.2% | 17.4% |

| Hispanic | 6.9% | 15.2% | 13.1% |

| White | 74.6% | 55.9% | 33.6% |

| Povertya | 29.8% | 64.7% | 79.1% |

| Individualized education plan/special education | 8.9% | 14.6% | 49.8% |

| Parental Incarceration | |||

| No history | 84.0% | 56.7% | 47.4% |

| Past | 14.1% | 36.7% | 35.8% |

| Current | 2.0% | 6.6% | 16.8% |

Youth were considered to be living in poverty if they endorsed any of the following 3 items: (1) “Do you currently get free or reduced-price lunch at school?” (2) “During the last 30 days, have you had to skip meals because your family did not have enough money to buy food?” and (3) “During the past 12, months, have you stayed in a shelter, somewhere not intended as a place to live, or someone else’s home because you had no other place to stay?”

Procedure

The 2013 Minnesota Student Survey was administered to students in the classroom during the spring semester. Students completed either a paper or an electronic version of the survey, depending on each school district’s preferred mode of survey administration. The students were asked to complete the survey in one sitting and were given no time constraint; survey authors estimated students took 35–50 minutes to complete the survey.

Youth in 8th, 9th, and 11th grades were asked: “Have any of your parents or guardians ever been in jail or prison?” Three response options were given, and youth were instructed to select all that applied: “none of my parents or guardians has ever been in jail or prison” (never); “yes, I have had a parent or guardian in jail or prison in the past” (past); “yes, I have a parent or guardian in jail or prison right now” (current).

Across all school settings, a majority of youth (83.4%, N = 95,822) reported their parent or guardian had never been incarcerated; 15% (N = 17,272) reported they had experienced the incarceration of a parent or guardian in the past; 2.1% (N = 2369) reported that a parent or guardian was currently in jail or prison. A small number of students (n = 635, < .5%) endorsed both current and former experience of incarceration. To create mutually exclusive categories for comparison (ie, never versus past versus current), we coded these youth as current. Parental incarceration status by school setting is reported in Table 1.

Achievement

Achievement was assessed with one item: “How would you describe your grades this school year?” Response options were mostly As, mostly Bs, mostly Cs, mostly Ds, mostly Fs, mostly incompletes, and none of these letter grades. Responses were dichotomized (1 = mostly As and Bs; 0 = all other responses).

Discipline

Discipline was assessed with 3 items: (1) “During the last 30 days, how many times have you been sent to the office for discipline?” (2) “During the last 30 days, how many times have you had in-school suspension?” and (3) “During the last 30 days, how many times have you been suspended from school (out-of-school suspension)?” Response options for all 3 items were none, once or twice, 3 to 5 times, 6 to 9 times, and 10 or more times. These 3 items were combined and dichotomized (no instances of disciplinary action = 0; one or more disciplinary actions = 1).

School connectedness

The Teacher-Student Relationship scale is a 5-item, validated assessment tool for measuring school connectedness.27 Youth were instructed to rate each item on a 4-point Likert-type scale, ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (4): (1) “Overall, adults at my school treat students fairly.” (2) “Adults at my school listen to the students.” (3) “The school rules are fair.” (4) “At my school, teachers care about students.” and (5) “Most teachers at my school are interested in me as a person.” The 5 items were then reverse scored and averaged to create a continuous measure of school connectedness, in which higher scores indicated more school connectedness (Range = 0–4). The scale demonstrated adequate reliability across school settings, with alphas ranging from .86 to .88.

Student engagement

Student engagement was assessed using 2 items: “How often do you care about doing well in school?” and “How often do you pay attention in class?” Response options for both items were: all of the time (1), most of the time (2), some of the time (3), and none of the time (4). Responses were reverse scored and averaged to create a continuous measure of student engagement, where higher scores reflected more engagement (Range = 0–4). This measure demonstrated adequate reliability across school settings, with alphas ranging from .67 to .73.

Missing Data

Across all school settings, 114,828 youth (92% of youth surveyed) provided a response to the primary variable of interest regarding their experience with parental incarceration. Missing data analyses revealed no differences by age; however, youth who did not answer the parental incarceration question were more likely to be male, living in poverty χ2 (1, N = 4283) = 6437.88, p < .001, or identify as a racial minority χ2 (6, N = 4356) = 2628.99, p < .001. Youth who did not respond to the parental incarceration question were also more likely to have an individualized education plan or report receiving special education services χ2 (1, N = 1769) = 1049.71, p < .001. Less than 3% of participants did not respond to one or more of items that comprised the 4 measures of the academic outcomes; these cases were removed from subsequent analyses.

Data Analysis

We first examined descriptive statistics among key study variables for the entire sample and by school setting (Table 1). On the basis of these findings, we examined interactions between parental incarceration status (never, past, current) and school settings (public, Alternative Learning Center, Juvenile Correctional Facility), by regressing parental incarceration status, school setting, and the parental incarceration by school setting interaction term on each of the 4 dependent variables. The interaction term was significant in each model and on the basis of these findings, we stratified by school setting for all subsequent analyses.

We used logistic regression analyses for the 2 dichotomous dependent variables (achievement and discipline) and generalized linear models for the 2 continuous dependent variables (school connectedness and student engagement), to evaluate associations between parental incarceration status and academic outcomes, controlling for identified covariates, within each school setting.

RESULTS

Public Schools

Results from the logistic regression analyses for youth in all school settings are presented in Table 2. Among youth in public schools, the incarceration of a parent – both current and past parental incarceration – was significantly associated with youth’s achievement and discipline. Youth with a parent currently incarcerated had significantly lower odds of getting “As” and “Bs” compared to their peers with no history of parental incarceration (OR = 0.35, p < .01; 95% CI: 0.32–0.38). Further, youth who had a parent incarcerated in the past had significantly lower odds of receiving good grades than those who have never had an incarcerated parent (OR = 0.41, p < .01; 95% CI: 0.40–0.43).

Table 2.

Academic Achievement and Discipline, Adjusted Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals

| Academic Achievement | Discipline | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Public Schools | ||

| N | 105,749 | 107,297 |

| Age | 0.93 (0.92–0.94)** | 0.84 (0.83–0.86)** |

| Girls | Ref. | Ref. |

| Boys | 0.54 (0.52–0.56)** | 2.12 (2.03–2.21)** |

| White, non-Hispanic | Ref. | Ref. |

| All other race/ethnic groups | 0.73 (0.71–0.76)** | 1.56 (1.49–1.63)** |

| Poverty | 0.42 (0.41–0.44)** | 1.73 (1.65–1.81)** |

| Individualized education plan/special education | 0.34 (0.33–0.36)** | 2.01 (1.89–2.13)** |

| Parent never incarcerated | Ref. | Ref. |

| Parent incarcerated in the past | 0.41 (0.40–0.43)** | 2.44 (2.32–2.57)** |

| Parent currently incarcerated | 0.35 (0.32–0.38)** | 3.59 (3.24–3.97)** |

| Alternative Learning Centers | ||

| N | 1,617 | 1,638 |

| Age | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) | 0.76 (0.70–0.84)** |

| Girls | Ref. | Ref. |

| Boys | 0.42 (0.34–0.52)** | 1.97 (1.54–2.51)** |

| White, non-Hispanic | Ref. | Ref. |

| All other race/ethnic groups | 0.70 (0.56–0.86)** | 1.20 (0.94–1.53) |

| Poverty | 0.97 (0.77–1.21) | 1.18 (0.91–1.54) |

| Individualized education plan/special education | 0.63 (0.47–0.85)** | 1.35 (0.98–1.86) |

| Parent never incarcerated | Ref. | Ref. |

| Parent incarcerated in the past | 0.74 (0.60–0.93)** | 1.09 (0.84–1.41) |

| Parent currently incarcerated | 0.86 (0.56–1.33) | 2.50 (1.61–3.87)** |

| Juvenile Correctional Facilities | ||

| N | 281 | 292 |

| Age | 0.99 (0.82–1.19) | 0.81 (0.67–1.00) |

| Girls | Ref. | Ref. |

| Boys | 0.87 (0.50–1.51) | 0.79 (0.44–1.43) |

| White, non-Hispanic | Ref. | Ref. |

| All other race/ethnic groups | 1.10 (0.66–1.82) | 0.88 (0.51–1.53) |

| Poverty | 0.87 (0.49–1.82) | 0.97 (0.51–1.83) |

| Individualized education plan/special education | 0.88 (0.55–1.41) | 1.24 (0.73–2.09) |

| Parent never incarcerated | Ref. | Ref. |

| Parent incarcerated in the past | 0.94 (0.56–1.60) | 1.24 (0.69–2.23) |

| Parent currently incarcerated | 0.89 (0.44–1.80) | 2.05 (0.95–4.40) |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01

Parental incarceration was also significantly associated with disciplinary action among youth in public schools. Students who reported having a parent incarcerated in the past had nearly 2–1/2 times the odds (OR = 2.44, p < .01; 95% CI: 2.32–2.57) of reporting some instance of disciplinary action than those youth with no history of parental incarceration. Youth who were currently experiencing the incarceration of a parent had more than 3–1/2 times the odds (OR = 3.59, p < .01; 95% CI: 3.24–3.97) of being disciplined than youth who never had a parent in jail or prison.

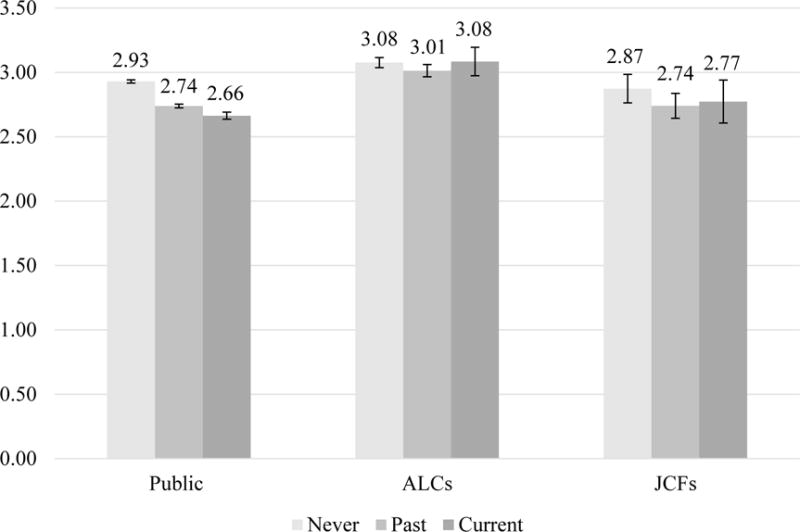

Results for school connectedness and student engagement are presented in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. Among youth in public schools, those youth who were currently experiencing the incarceration of a parent reported the lowest levels of school connectedness (M = 2.66). Further, youth who experienced the incarceration of a parent in the past reported significantly lower levels of school connectedness (M = 2.74) compared to their peers who had never experienced the incarceration of a parent (M = 2.93) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. School Connectedness by Setting, Marginal Means and 95% Confidence Intervals.

Note.

ALC = alternative learning centers; JCF = juvenile correctional facilities; Models adjust for youth age, sex, race/ethnicity, poverty status, and receipt of special education services.

Figure 2. Student Engagement by Setting, Marginal Means and 95% Confidence Intervals.

Note.

ALC = alternative learning centers; JCF = juvenile correctional facilities; Models adjust for youth age, sex, race/ethnicity, poverty status, and receipt of special education services.

A similar pattern emerged for youth’s self-reported school engagement. Youth who were currently experiencing a parent’s incarceration reported significantly lower levels of school engagement (M = 2.84), compared to youth who had experienced a parent’s incarceration in the past (M = 2.95). Further, youth who reported parental incarceration in the past reported significantly lower levels of school engagement than those who had never experienced parental incarceration (M = 3.18; Figure 2).

Alternative Learning Centers

Youth with a history of parental incarceration had significantly lower odds (OR = 0.74, p < .05; 95% CI 0.60–0.93) of earning “As” and “Bs” compared to their peers whose parents had never been incarcerated. In addition, youth in alternative learning centers who reported having a parent or guardian currently in jail or prison had 2–1/2 times the odds (OR = 2.50, p < .01; 95% CI: 1.61–3.87) of experiencing disciplinary action than their peers who reported no history of parental incarceration. There were no significant differences among youth’s self-reported school connectedness by their history of parental incarceration (Figure 1). However, there were significant differences in youth’s self-reports of student engagement. Youth in alternative learning centers who had a parent currently incarcerated reported significantly lower levels of engagement (M = 2.78) compared to their peers with a history of parental incarceration (M = 2.97) and those who had never experienced a parent’s incarceration (M = 3.02; Figure 2).

Juvenile Correctional Facilities

Among youth in juvenile correctional facilities, parental incarceration status was not significantly associated with achievement, disciplinary action, self-reported school connectedness, or engagement (Figures 1 & 2).

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study revealed that parental incarceration was significantly associated with students’ school-related outcomes. However, this effect varied markedly by school setting. Among youth in public school settings, parental incarceration was consistently associated with poor school outcomes; yet, there were mixed findings for youth in alternative learning centers and no significant effects across any of the outcomes for youth in juvenile correctional facilities.

Public Schools

Among youth in public schools, parental incarceration was consistently associated with worse school outcomes. Youth who were currently experiencing the incarceration of a parent or who had experienced the incarceration of a parent in the past reported lower levels of achievement, less engagement and connectedness, and greater likelihood of receiving disciplinary action compared to their peers who had never experienced the incarceration of a parent.

Our results are consistent with other researchers who have documented the deleterious consequences of parental incarceration among children’s academic achievement.16,18,19 In their report, Turney and Haskins16 offered 3 possible mechanisms by which parental incarceration may be linked to poor academic outcomes, which can be considered in light of our current findings.

First, a child’s separation from her parent as a result of the parent’s incarceration may be a traumatic experience. Such trauma could lead to behavior problems, which could in turn impact the child’s academic outcomes. The second proposed mechanism suggested that a parent’s incarceration stigmatizes the child and family, leading to feelings of isolation and shame with negative consequences for the child’s well-being and adjustment. The third mechanism acknowledged that a parent’s incarceration often creates strain in the family system, through the loss of income, disruption in parenting roles, housing mobility, and conflict in the co-parenting relationship. As a result, this strain can compromise children’s adjustment and negatively impact their school performance. Our data do not allow us to test these mechanisms.

We were, however, able to examine whether those youth that were currently experiencing the incarceration of a parent fared worse than their peers who have experienced parental incarceration in the past. Our results consistently demonstrated that the current incarceration of a parent had a more profound and negative impact than the incarceration of a parent in the past in both public schools and alternative learning centers. One explanation for this differential effect between current and past parental incarceration may be that youth who were currently experiencing a parent’s incarceration may have also experienced a recent trauma. For example, the youth may have experienced the arrest of the parent or a change in their caregiving situation that would have also impacted their current adjustment at home and in school. While a parent’s past incarceration may also signal some level of family disruption, it is possible that the time since the parent’s incarceration provided an opportunity for the family and the youth to re-stabilize. Therefore, past parental incarceration may have a less pronounced impact on youth’s current academic functioning.

Alternative Learning Centers

A different pattern – and one that was inconsistent with our hypotheses – emerged among youth attending alternative learning centers. Past (but not current) parental incarceration was significantly associated with reduced odds of earning As and Bs. In contrast, current (but not past) parental incarceration was significantly associated with increased odds of disciplinary action. Further, youth in alternative learning centers who had a currently or formerly incarcerated parent reported significantly lower levels of engagement than their peers who had never experienced a parent’s incarceration. This unexpected pattern of results may be attributed to the diversity of youth attending and the varied reasons for their referrals to alternative learning centers. These results point to the complex interactions between parental incarceration and other academic risk factors for young people, and points to the need for further study of how parental incarceration impacts youth differently across school settings.

Juvenile Correctional Facilities

For youth in juvenile correctional facilities, and unlike youth in public schools or alternative learning centers, neither past nor current parental incarceration were significantly associated with any of the school outcomes examined in this study. There are several possible explanations for why we did not find independent effects for parental incarceration on academic outcomes among youth in juvenile correctional facilities. First, we may have been statistically underpowered, as only 169 students in juvenile correctional facilities reported currently experiencing or previously experiencing a parent’s incarceration. Second, an inherent challenge in any of the research examining the effects of parental incarceration on youth outcomes is the fact that incarceration, either a youth’s incarceration in a juvenile detention center or a parent’s incarceration in jail or prison, does not occur at random.28 Many of the factors that are significantly associated with incarceration – being male and from a racial minority group, living in poverty, receiving special education services – are also related to youth’s academic outcomes. Most youth detained in juvenile correctional facilities have already faced considerable adversity and systemic disadvantage across their young lives. Thus, it may be no surprise that the incarceration of a parent has no independent effect on their school outcomes.

One explanation for the differences in findings across school settings relates to stigma. It is possible that among youth in public schools, a setting in which parental incarceration is less common than alternative learning centers or juvenile correctional facilities, that youth with incarcerated parents feel more isolated and have fewer peers with whom they can relate their family’s circumstances. It is also possible that teachers in public school settings have less exposure to parental incarceration, and may therefore have negative perceptions that lower their expectations for youth with incarcerated parents. Such perceptions could reduce youth’s feelings of school connection and classroom engagement and could subsequently impact their academic performance. Such bias may be less common among teachers in alternative learning centers and juvenile correctional facilities, who may be more likely to encounter youth who have complex family histories and thus have a different set of expectations for youth in these settings.

Previous experimental work may provide some support for this explanation. In their study, Dallaire and colleagues29 found that teachers rated fictitious children with incarcerated mothers as less competent than children whose mothers were described as absent for other reasons. Thus, public school teachers may have lower expectations for youth with incarcerated parents, which could in turn lead to poor academic outcomes. Recently, Turney and Haskins16 found that elementary school children with incarcerated fathers were more likely to experience grade retention than their peers who had not experienced paternal incarceration, and that these differences were not explained by lower test scores or other standard academic measures. Instead, their results suggested that the differences were best explained by teachers’ negative biases and lowered expectations of children with incarcerated parents, providing support for the idea that stigma leads to poor academic outcomes. Additional research is needed to understand the mechanisms by which parental incarceration impacts youth’s academic outcomes and how these mechanisms may vary across school settings.

Limitations

The current study has several limitations that must be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the study relied exclusively on students’ self-reports. Students, especially younger students, may be inclined to misrepresent their academic or behavioral performance.30 Thus, combining students’ self-reports with teachers’ reports and/or administrative records, especially on students’ achievement and disciplinary action, would strengthen future studies. Second, the current study could not account for variations in academic, social, and disciplinary contexts across schools. Whereas one school’s policy might dictate an out-of-school suspension for a physical fight, another school may opt for an in-school suspension or no disciplinary action at all. In particular, disciplinary actions might have a very different meaning for youth in juvenile correctional facilities or alternative learning centers versus those in mainstream public schools.

Another limitation relates to potential unmeasured selection effects. The data for this study were drawn from a single state, and results might not be generalizable to the population of children with incarcerated parents. Although all school districts in the state were invited and encouraged to participate, one large public school district in in an urban area opted not to have their students complete the survey. Given the concentration of social disadvantage, crime, and incarceration in urban areas,31,32 however, we suspect that results in the present study may actually underrepresent the true number of youth impacted by parental incarceration. Similarly, the Minnesota Student Survey only surveys youth currently attending school. Those youth who drop out of school are presumably at highest risk for academic difficulties and may be disproportionally affected by parental incarceration; thus our findings are likely conservative estimates of the impact of parental incarceration on youth’s academic outcomes. Similarly, while we know that the majority of youth in public schools in the state responded to the survey, response rate are unavailable for alternative learning centers and juvenile correctional facilities. Furthermore, children with an individualized education plan were more likely to be missing data about their experience of parental incarceration. It is possible that these children are most likely to experience school failure and lower levels of connectedness to school, and thus, the impact of parental incarceration on school outcomes could be underestimated.

Finally, the survey’s single item about the incarceration of a parent or guardian leaves many questions unanswered. No information was collected about the youth’s guardianship, which parent or guardian was incarcerated, and the circumstances of that individual’s incarceration. For example, no information was collected about the frequency or duration of the parent’s incarceration or the youth’s home environment before, during, or after the incarceration. Previous research has found that children of incarcerated parents are often at higher risk for poor outcomes, even when the incarcerated parent did not live with the child prior to the parent’s arrest.33 Additional information about the youth’s caregiver(s) both during and after incarceration, disruptions in the home and school environments as a result of the parent’s incarceration, and the incarcerated parent’s role upon release are all valuable areas for future inquiry. The data used in this study are cross-sectional and cannot be used to support causal inferences about the effect of parental incarceration on academic outcomes. Because prospective longitudinal studies on this topic are relatively rare (see Murray34 for a review), cross-sectional datasets become valuable sources for scientific inquiry. Although we were not able to test the potential mechanisms by which parental incarceration impacts youth’s school outcomes in the current study, this is a valuable area for future scientific inquiry. With cross-sectional data and limited information, critical questions are left unanswered about when in the child’s life course the parent’s incarceration occurred, how this timing impacts their adjustment, and the mechanisms by which parental incarceration impacts school outcomes.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, this study has many strengths. First, the sample size is very large, allowing us to consider a group of youth who are often underrepresented in survey research, namely those with currently or formerly incarcerated parents. This is the first time that this statewide survey included an item about parental incarceration; as such, the current study adds to a small, but growing body of literature on the impact of this adverse childhood experience on youth’s outcomes. Additionally, we were able to include data from youth attending public schools, alternative learning centers, and juvenile correctional facilities with a high response rate. Thus, the findings likely represent a cross-section of youth in the state.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOL HEALTH

Whereas these data and our analyses were limited in their ability to test the potential mechanisms of risk, the current study adds to a body of literature demonstrating the negative effects of parental incarceration on youth’s educational outcomes, particularly for youth in public school settings. Such findings have important implications for school systems and educators. Teachers and administrators should consider the following actions:

Screen for youth’s history of adverse childhood experiences, including the incarceration of a parent, on registration or health forms.

When teachers and school personnel who know that a youth has an incarcerated parent, collaborate with the youth and his caregivers to identify opportunities for intervention within and outside of school, including school-based peer support groups, tutoring, and mentoring.

Provide training for teachers and administrators on parental incarceration and its effects on youth. Existing evidence suggests that teachers might have specific biases about children with incarcerated parents, and teacher bias in general is known to have a detrimental impact students.35 Interventions that aim to reduce social stigma and potential bias among teachers and administrators may be one approach to reducing academic disparities for these vulnerable young people.

Teachers and administrators are tasked with educating students who are increasingly more likely to come from complex and disrupted home environments, which may interfere with their success in school. Future research should continue to address the impact of parental incarceration on youth’s school-based outcomes, with the goal of identifying opportunities for successful prevention and intervention.

Human Subjects Approval Statement

This study utilized completely de-identified data drawn from a public data source. As such, this study was deemed exempt from human subjects review and no institutional review was required.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number UL1TR000114. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Rebecca J. Shlafer, Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Health, University of Minnesota, 717 Delaware Street SE, Minneapolis, MN 55414, Phone: 612-625-9907.

Tyler Reedy, Youth Housing Case Manager, Amherst H. Wilder Foundation, 451 Lexington Parkway North, Saint Paul, MN 55104, Phone: 515-943-3792.

Laurel Davis, Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Pediatrics, Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Health, University of Minnesota, 717 Delaware Street SE, Minneapolis, MN 55414, Phone: 612-626-6787.

References

- 1.Pew Charitable Trusts. Collateral costs: incarceration’s effect on economic mobility. 2010 Available at: http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2010/collateralcosts1pdf.pdf. Accessed June 3, 2017.

- 2.Travis J, McBride EC, Solomon AL. Families left behind: the hidden costs of incarceration and reentry. 2005 Available at: http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/50461/310882-Families-Left-Behind.PDF. Accessed June 3, 2017.

- 3.Eddy JM, Poehlmann J. Children of Incarcerated Parents: A Handbook of Researchers and Practitioners. Washington DC: The Urban Institute Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee RD, Fang X, Luo F. The impact of parental incarceration on the physical and mental health of young adults. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):e1188–e1195. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roettger ME, Boardman J. Parental incarceration and gender-based risks for increased body mass index: evidence from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(7):636–644. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbott-Chapman J, Martin K, Ollington N, Venn A, Dwyer T, Gall S. The longitudinal association of childhood school engagement with adult educational and occupational achievement: findings from an australian national study. Br Educ Res J. 2014;40(1):102–120. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perra O, Fletcher A, Bonell C, Higgins K, McCrystal P. School-related predictors of smoking, drinking and drug use: evidence from the Belfast Youth Development Study. J Adolesc. 2012;35(2):315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Topitzes J, Godes O, Mersky JP, Ceglarek S, Reynolds AJ. Educational success and adult health: findings from the Chicago longitudinal study. Prev Sci. 2009;10(2):175–195. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0121-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vacca JS. Educated prisoners are less likely to return to prison. J Correct Educ. 2004;55(4):297–305. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster H, Hagan J. Intergenerational school effects of mass imprisonment in America. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2009;623(1):179–194. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng IYH, Sarri RC, Stoffregen E. Intergenerational incarceration: risk factors and social exclusion. J Poverty. 2013;17(4):437–459. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neal MF. Doctoral Dissertation. Johnson City, TN: East Tennessee University; 2009. Evaluating the school performance of elementary and middle school children of incarcerated parents. Available at: http://dc.etsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3240&context=etd&sei-redir=1&referer=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.bing.com%2Fsearch%3Fq%3DEvaluating%2Bthe%2Bschool%2Bperformance%2Bof%2Belementary%2Band%2Bmiddle%2Bschool%2Bchildren%2Bof%2Bincarcerated%2Bparents%26form%3DIE10TR%26src%3DIE10TR%26pc%3DEUPP_MATBJS#search=%22Evaluating%20school%20performance%20elementary%20middle%20school%20children%20incarcerated%20parents%22. Accessed June 3, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon L. Invisible Children: First Year Research Report A Study of the Children of Prisoners. Christchurch, New Zealand: Pillars, Inc; 2009. Available at: http://www.rethinking.org.nz/images/newsletterPDF/Issue70/05Invisible_children.pdf. Accessed June 3, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray J, Loeber R, Pardini D. Parental involvement in the criminal justice system and the development of youth theft, marijuana use, depression, and poor academic performance. Criminology. 2012;50(1):255–302. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quilty S, Levy M, Howard K, Barratt A, Butler T. Children of prisoners: a growing public health problem. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2004;28(4):339–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2004.tb00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turney K, Haskins AR. Falling behind? Children’s early grade retention after paternal incarceration. Sociol Educ. 2014;87(4):241–258. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanlon T, Blatchley R, Bennett-Sears T, O’Grady K, Callaman J. Vulnerability of children of incarcerated addict mothers: implications for preventive intervention. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2005;27:67–84. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trice AD, Brewster J. The effects of maternal incarceration on adolescent children. J Police Crim Psychol. 2004;19(1):27–35. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huynh-Hohnbaum A, Bussell T, Lee G. Incarcerated mothers and fathers: how their absences disrupt children’s high school graduation. Int J Psychol Educ Stud. 2015;1:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray J, Farrington DP, Sekol I. Children’s antisocial behavior, mental health, drug use, and educational performance after parental incarceration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2012;138(2):175–210. doi: 10.1037/a0026407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho RM. Impact of maternal imprisonment on children’s probability of grade retention. J Urban Econ. 2009;65:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho RM. The impact of maternal imprisonment on children’s educational achievement: results from children in Chicago public schools. J Hum Resour. 2009;44(3):772–797. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carson E. Prisoners in 2014 (NCJ 248955) Washington DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2015. Available at: http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5387. Accessed June 3, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hockenberry S. Juveniles in Residential Placement, 2011. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2014. Available at: http://www.ojjdp.gov/pubs/246826.pdf. Accessed June 3, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minnesota Department of Education. State Approved Alternative Programs Resource Guide. Roseville, MN: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swayze D, Buskovick D. Youth in Minnesota Correctional Facilities: Responses to the 2010 Minnesota Student Survey. St. Paul, MN: Department of Public Safety; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Appleton JJ, Christenson SL, Kim D, Reschly AL. Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: Validation of the student engagement instrument. J Sch Psychol. 2006;44(5):427–445. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pettit B, Western B. Mass imprisonment and the life course: race and class inequality in U.S. incarceration. Am Sociol Rev. 2004;69(2):151–169. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dallaire DH, Ciccone A, Wilson LC. Teachers’ experiences with and expectations of children with incarcerated parents. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2010;31:281–290. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teye AC, Peaslee L. Measuring educational outcomes for at-risk children and youth: issues with the validity of self-reported data. Child Youth Care Forum. 2015;44(6):853–873. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bobo LD. Crime, urban poverty, and social science. Du Bois Rev Soc Sci Res Race Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race. 2009;6(2):273–278. 6:273–278. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodriguez N. Concentrated disadvantage and the incarceration of youth: examining how context affects juvenile justice. J Res Crime Delinq. 2013;50(2):189–215. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geller A, Garfinkel I, Cooper CE, Mincy RB. Parental incarceration and child wellbeing: Implications for urban families. Soc Sci Q. 2009;90(5):1186–1202. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00653.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray J. Longitudinal research on the effects of parental incarceration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. In: Eddy JM, Poehlmann J, editors. Children of Incarcerated Parents. Washington DC: The Urban Institute Press; 2010. pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper CW. The detrimental impact of teacher bias: lessons learned from the standpoint of African American mothers. Teacher Education Quarterly. 2003;30(2):101–116. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hagan J, Foster H. Intergenerational educational effects of mass imprisonment in America. Sociol Educ. 2012;85(3):259–286. [Google Scholar]