Abstract

Commensal gut bacteria reinforce the gender bias observed in an autoimmune form of diabetes.

The gender bias observed in numerous diseases has long been understood as an entirely host-intrinsic factor. It is autoimmune conditions (inappropriate immune responses that attack self antigens and destroy host tissue) including type 1 diabetes mellitus, in which sex hormones affect disease susceptibility and severity (1, 2). On page 1084 of this issue, Markle et al. (3) introduce an astonishing twist to this view, suggesting that gender bias may be exercised and/or reinforced by the commensal microbiota of the host. This extrinsic, albeit commensal, factor appears to regulate sex hormone levels and arguably the gender bias observed in type 1 diabetes mellitus. The finding contributes to an expanding field of translational research aiming to convert our growing knowledge of the host-microbiota relationship into therapeutic approaches.

In recent years, the worldwide prevalence of autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes mellitus, inflammatory bowel disease, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis has been rising, pointing to a role of the environment in these disorders. The so-called “hygiene hypothesis” (4) has cast early-life environmental exposures as a determinant of later-life susceptibility to diseases with an immune-mediated etiology (such as asthma). Such early-life environmental events may confer susceptibility to auto-immune disease through functional alterations of commensal microbiota in the gut (5). Indeed, in several autoimmune disease models, the development of tissue injury can be prevented under axenic (germ-free) conditions wherein microbiota are absent or in other cases where they are altered (2, 3, 6). This raises the hope that beneficial properties of the microbiota may be transferable, and forms the basis for microbial transplantation and similar types of manipulation as therapies for autoimmune diseases.

Markle et al. show that the pronounced sensitivity of female mice versus resistance of male mice to type 1 diabetes mellitus [in the non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse model, which confers genetic susceptibility to this disorder] could be directly attributed to the commensal microbiota. Specifically, the authors observed that the composition of the commensal microbiota of male and female animals diverged at the time of puberty, which implies that maleness and femaleness exerted specific influences on the composition of the microbiota. Removal of the microbiota increased the circulating testosterone concentration in female mice but decreased the concentration in male mice. This suggests a bidirectional interaction between the amount of male sex hormone and the microbiota. Thus, puberty in males (and, although not directly demonstrated, testosterone) may orchestrate alterations in the commensal microbiota, and the microbiota may “record” the state of maleness, which is then “played back” to the host in a self-reinforcing program of masculinization (see the figure).

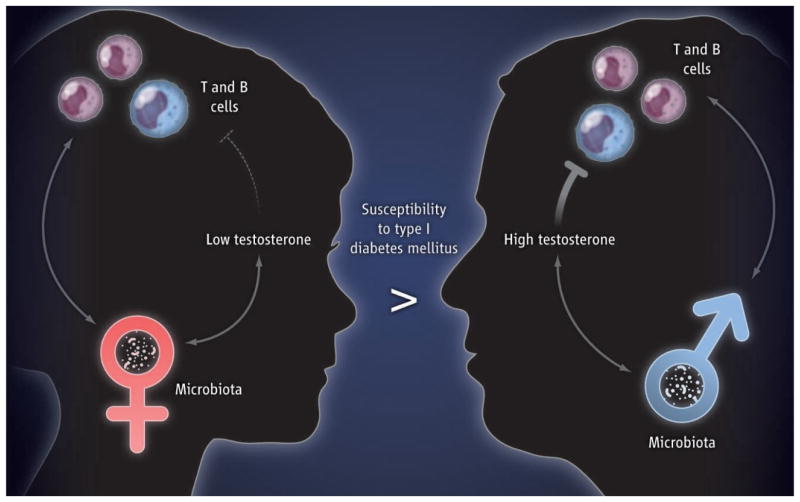

Figure. Gender, microbes, and disease.

Male puberty (in mice; not shown) leads to changes in the gut microbiota that reinforce testosterone production, which is protective against the development of T and B cell functions linked to autoimmune disease. In mice, the protective properties of the male-associated microbiota can be transferred to younger females and confer testosterone-mediated protection from autoimmune disease upon the recipients.

Markle et al. further demonstrate that the effect of bidirectional interaction between the host and microbes on disease susceptibility can be transferred between animals. Protection from type 1 diabetes mellitus was lost when male mice were made germ-free (there was also a decrease in testosterone concentration in this context); this observation is consistent with the protective effects of testosterone on the development of the disorder (1). The protective effects of the commensal microbiota on the full development of T and B cell responses associated with type 1 diabetes mellitus could be transferred during early life from male mice to female mice. Such transfer of masculinized microbiota to young female mice was associated with conferring a metastable state of maleness to the commensal microbiota of the female recipients, as shown by increases and decreases of specific microbes that were characteristic of male mice. These changes in the microbiota induced by fecal transfer were further associated with increased amounts of testosterone and a testosterone-dependent metabolite profile in the female recipients.

The ability of the microbiota as a whole to transfer and induce characteristics associated with both detrimental and beneficial phenotypes, as shown by Markle et al., has been demonstrated in a number of instances. Transfer of the microbiota from obese mice induced obesity in previously lean recipient mice (7). Transplanting microbiota from children suffering from kwashiorkor into mice, when combined with a suboptimal diet, resulted in weight loss in these mice, but not in mice with conventional microbiota fed the same diet (8). Furthermore, a clinical trial on the efficacy of fecal transplants from healthy individuals into patients suffering from recurrent Clostridium difficile infections in the gut, who are unresponsive to the conventional treatment based on antibiotics, has yielded encouraging results (9).

Characterizing the interactions between individual species within the commensal microbial community and the host has revealed potential mechanisms that may underlie such biologic outcomes. For example, Bacteroides fragilis and segmented filamentous bacteria regulate the deviation of T cells into specific fates (10, 11). And a protective effect of segmented filamentous bacteria in female, but not male, mice against the development of type 1 diabetes mellitus has been demonstrated (2). It would thus be interesting to determine whether colonization by segmented filamentous bacteria in female mice augments testosterone production. Along similar lines, antibiotic-induced reduction in commensal microbiota in early, but not adult, life distorts the quantity and function of invariant natural killer T cells in mucosal tissues and poises the host for heightened sensitivity to environmental agents that incite asthma and inflammatory bowel disease (5). Thus, age-specific interactions of the host with specific microbes may exert beneficial and/or detrimental influences on the biology of the host, including either protection from or susceptibility to autoimmune disease.

These observations raise the possibility that identifying the responsible host or microbial factors will allow for their therapeutic addition or removal. However, our current knowledge of such manipulation is very limited, with the potential for unforeseen adverse consequences. Although the effect may be durable to displace pathogenic species, it is not clear that it will be stable enough to afford long-lasting changes. Furthermore, microbiota transfer studies in human, mouse, and rat reveal a high degree of host specificity of the gut microbiota (12). Efficient colonization and associated effects also seem to be most successful in young animals, likely because their microbiota is not yet stabilized (6, 13). But the study by Markle et al. invites the intriguing question of the possible transfer of protective microbiota from pubertal human males to younger females during early life, when the commensal microbiota are amenable to the introduction of microbial successors (13). If so, family units with fathers and older brothers may offer a unique, unanticipated benefit for the health of their young daughters and sisters.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants DK044319, DK051362, DK053056, and DK088199 and Harvard Digestive Diseases Center grant DK0034854 (R.S.B.) and by a Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America research fellowship (M.B.F.).

References and Notes

- 1.Fox HS. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1409. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.5.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kriegel MA, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:11548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108924108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markle JGM, et al. Science. 2013;339:1084. doi: 10.1126/science.1233521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumberg R, Powrie F. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:137rv7. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olszak T, et al. Science. 2012;336:489. doi: 10.1126/science.1219328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wen L, et al. Nature. 2008;455:1109. doi: 10.1038/nature07336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turnbaugh PJ, et al. Nature. 2006;444:1027. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith MI, et al. Science. 2013;339:548. doi: 10.1126/science.1229000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Nood E, et al. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atarashi K, et al. Science. 2011;331:337. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivanov II, et al. Cell. 2009;139:485. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung H, et al. Cell. 2012;149:1578. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho I, et al. Nature. 2012;488:621. doi: 10.1038/nature11400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]