Photo: Alkan Yilmaz

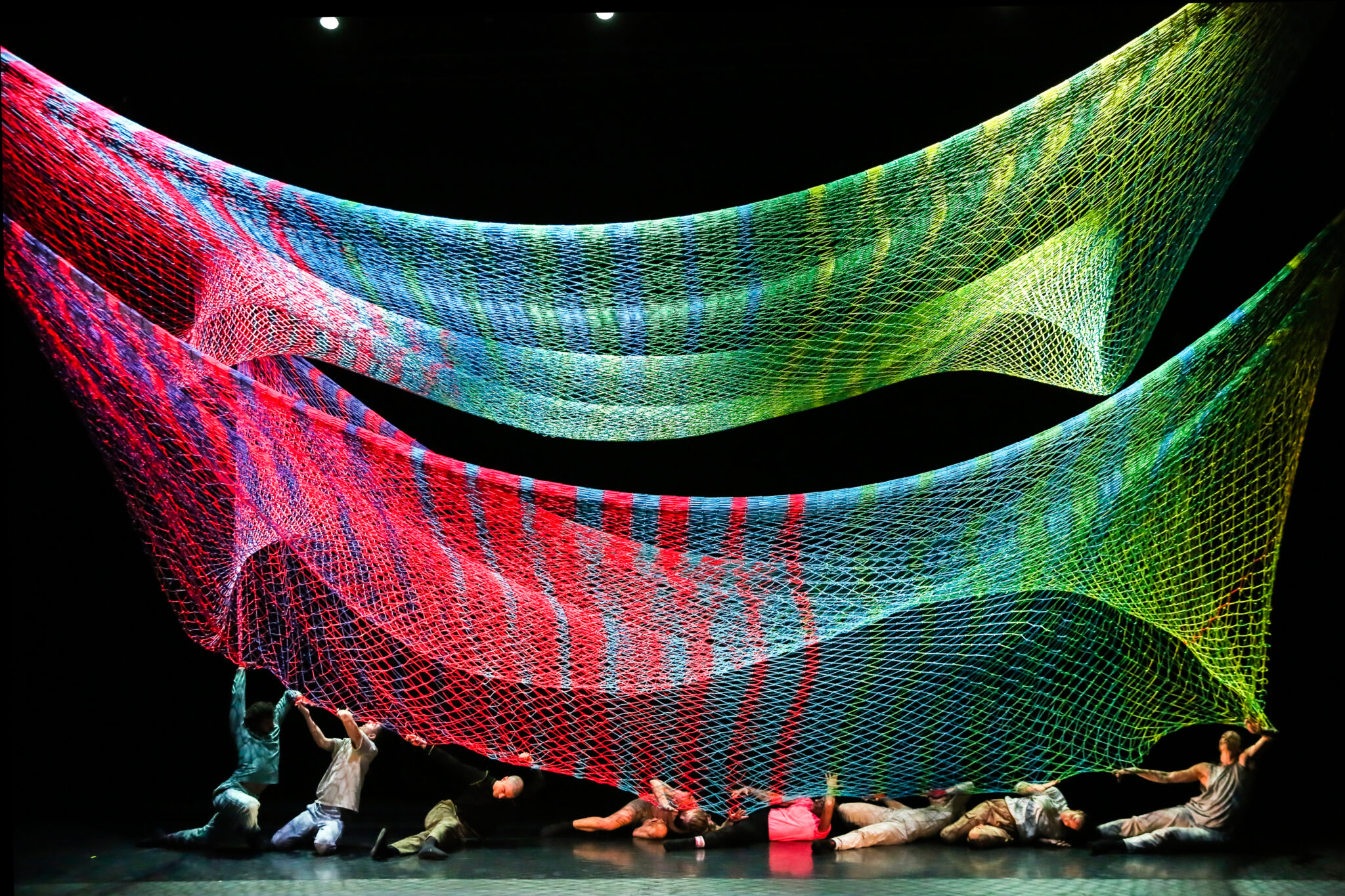

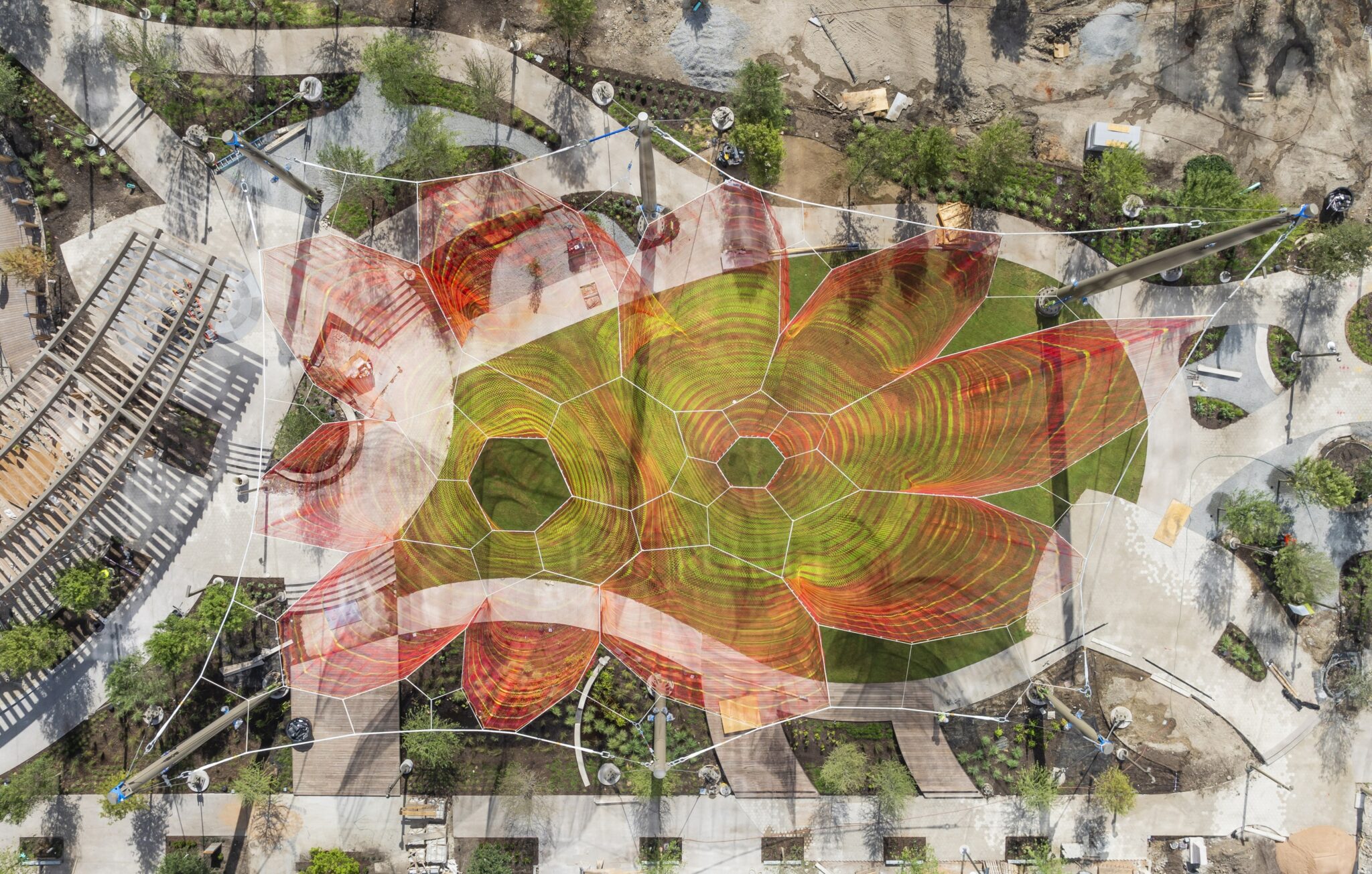

In the late 1990s, Janet Echelman, then a painter, traveled to India only for her paints to eventually go missing. When she landed in a fishing village, she quickly pivoted, creating sculptures with knotted fishing twine. These early experiments still inform Echelman’s practice decades later, which primarily revolves around monumental fiber installations. Today, she has embedded her vibrant, mesh-like sculptures in cities around the world, ranging from Singapore, London, and Vancouver to Porto, Santiago, and New York.

“I’m drawn to art that becomes part of daily life, which meets you where you are,” Echelman tells My Modern Met. “I’m most delighted with a public art project when it brings people together across different backgrounds, age, education, and cultures.”

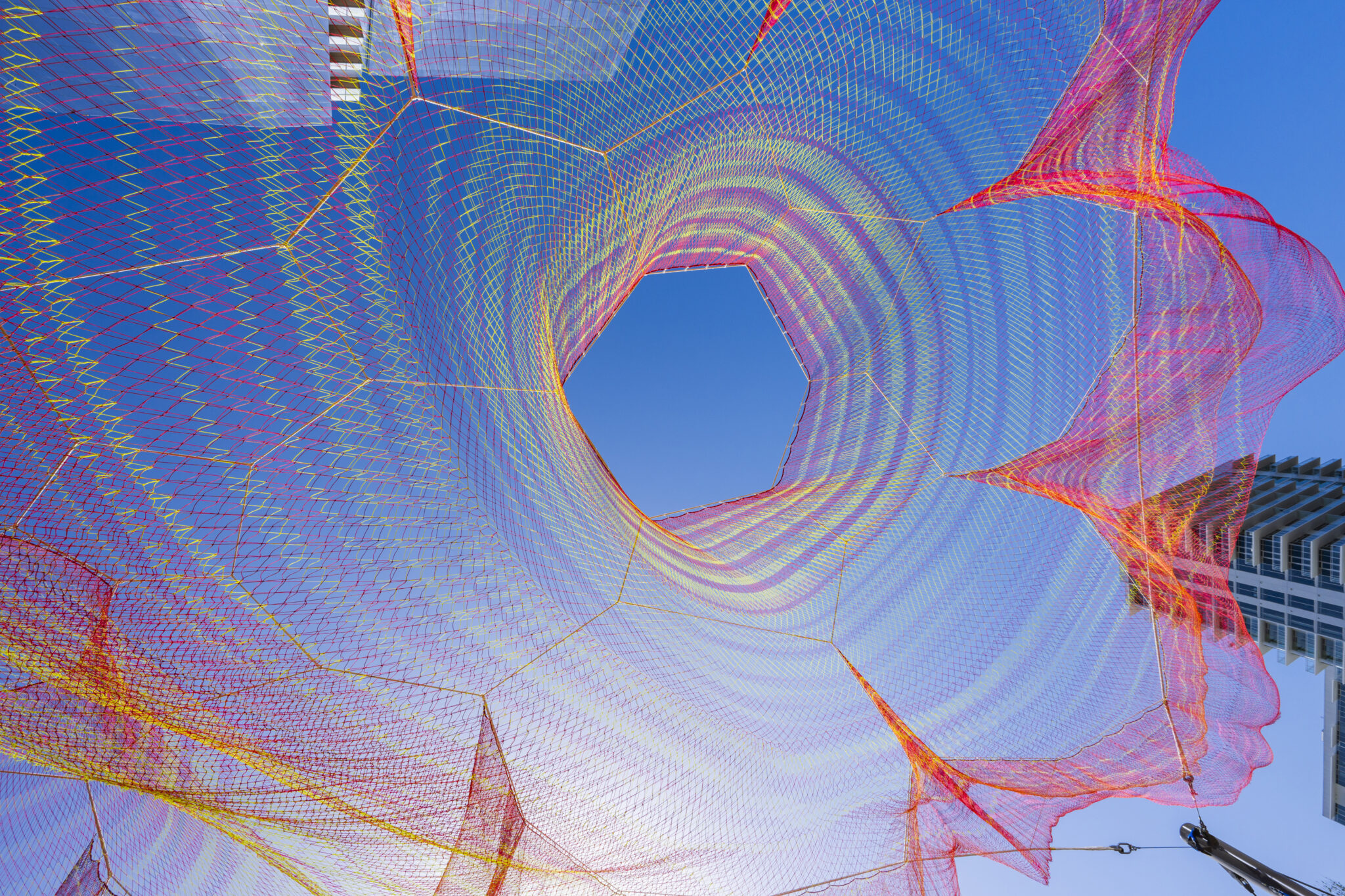

It’s hard not to encounter one of Echelman’s sculptures and not experience a sense of awe. Whether stretching across buildings or suspended in the air, these pieces practically vibrate with texture, depth, and color. The artist boasts an incredible command over setting and environment, understanding with granular detail how her pieces will evolve organically depending on wind or time of day.

“I began using knotted fiber netting on tall steel masts that interacted with nature, dancing with the choreography of wind,” she says of her creative evolution. “I then began exploring colored light that changes very slowly through time, like the speed of a sunset.”

But Echelman doesn’t only create massive public art. In the 2010s, she began showcasing her first interior works, including an installation designed for the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery. There, visitors would “come inside” the artwork, lie down on a custom-made carpet, and gaze up at the knotted sculpture above them.

“[They’d] watch the colored shadows projected on the walls move and change for the time it would take the sun to set,” Echelman adds. Another Smithsonian installation that the artist produced involved “colored shadow drawings” that danced across the gallery. “[Visitors] get lost inside the work, and total strangers start talking to each other about what they’re experiencing.”

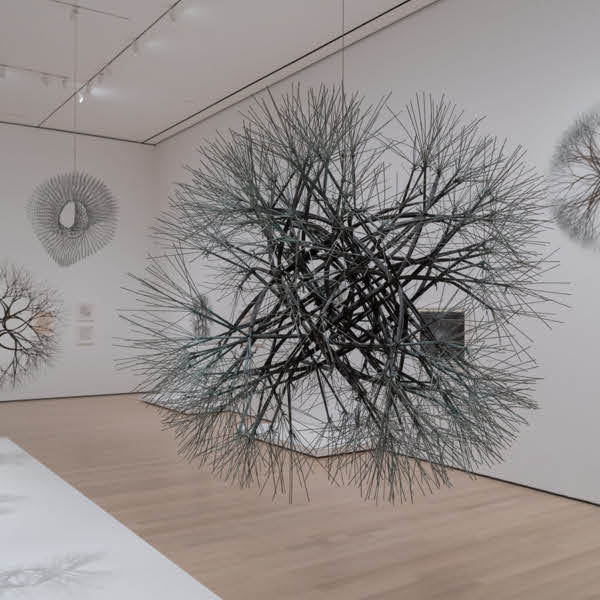

Though she’s been at the forefront of fiber art for years, Echelman has also noticed how much traction the medium is gaining throughout mainstream art institutions.

“It doesn’t surprise me that art with physical craftsmanship and attention to materials and craft traditions are getting a lot of love in the art world right now,” she says. “I see this as a response to screen time and virtual experiences. It’s one thing to play a video of someone standing beneath a flowing waterfall, and another to feel the force of that cool water pelting down upon your head.”

It should come as no surprise, then, that Echelman remains a pioneer in her field, curating tactile experiences rather than static, two-dimensional moments. After all, in the artist’s own words, her work uses “physical materials and craft methods that have been passed down from generation to generation.” And, thanks to her new book with Princeton Architectural Press, Radical Softness, viewers can get an even better glimpse into Echelman’s craft methods.

“For me as an artist, when you enter the art and create your own meaning,” she says, “that is what completes the work.”

For decades, artist Janet Echelman has created monumental fiber installations in cities around the world.

Photo: Marinco Kojdanovski

Photo: Brian Adams

Photo: Joao Ferrand

Photo: Ema Peter

Photo: Enrique Diaz

Photo: Infinite Impact

Photo: Julie Lemberger

Echelman’s sculptures are tactile and designed for the public, inviting visitors to witness how their colors evolve as the day progresses.

Photo: David Feldman

Photo: Payne Wingate and Eric Gavin

Photo: Janusvanden Eijnden

Photo: Simon J. Nicol

Photo: Payne Wingate and Eric Gavin

Photo: Janet Echelman

Her new book, Radical Softness, explores her storied career and her enduring legacy in fiber art and craftsmanship.

Photo: Janet Echelman

Photo: Janet Echelman

Photo: Smithsonian Institution

Photo: Nicole Wang

Photo: Melissa Henry

Photo: Amy Martz and the Majeed Foundation

Photo: Melissa Henry