A High-Stakes Policy Debate on Reducing Urban Poverty

One of my favorite economists has co-authored a searing Opinion Piece in the Wall Street Journal. What do economists now know about cost-effectively reducing urban poverty?

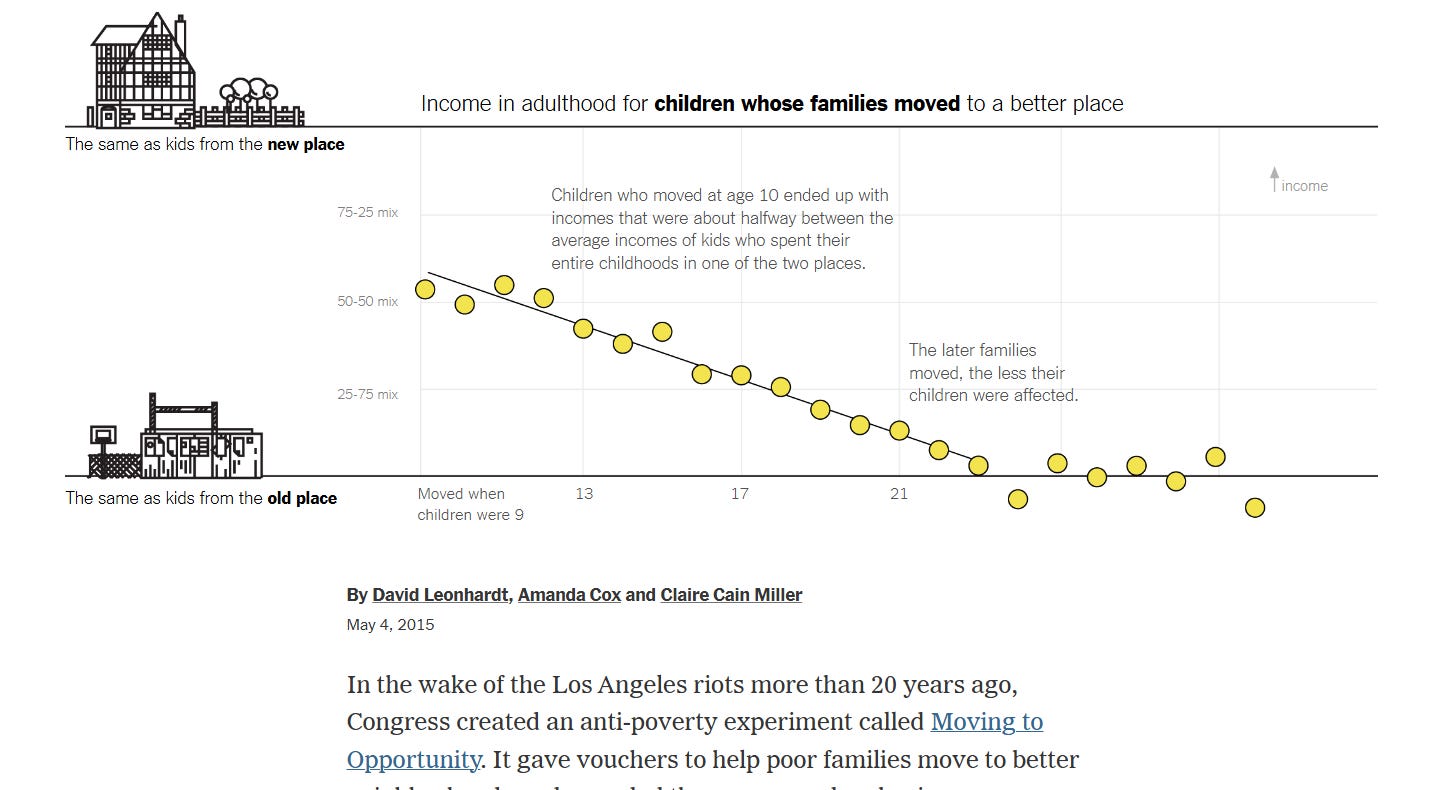

Jim Heckman’s co-authored piece takes a scientific look at this important research by Chetty and Hendren. You can read their papers here. Here is a figure from the New York Times highlighting their core findings.

The lesson you are supposed to learn from the figure above is that disadvantaged kids who move at a younger age to a better neighborhood achieve later life earnings that resemble their destination neighborhood’s peers. The “causal effect” here is the claim that if society could move more young disadvantaged kids to better neighborhoods that this would help them to flourish in later life.

Raj Chetty and coauthors have argued that many poor people who would benefit from such moves are unaware of what they would gain. He has employed a type of “concierge” approach, gently coaching them in Seattle to relocate to better neighborhoods. Here is his Seattle co-authored paper.

Better communities feature higher rents and poor people face a challenge in paying the rent in such areas. Housing vouchers are a policy where the government subsidizes the rent to allow poor people to “move to opportunity”. The American Taxpayers pay this bill.

Point #1 The Chetty policy proposal of subsidizing and nudging poor people to move to areas that they pinpoint as having later life value added is expensive. There are alternative uses for this $, including investing in coaching parents to improve their interactions with their kids to nurture their early development. Heckman’s research team is investigating cost-effective strategies for promoting child skill development across multiple dimensions of character building.

Point #2 The Chetty policy alleviation policy is a first cousin of the Abundance Movement (see Klein and Thompson). If Chetty and the Data Scientists can use life-cycle IRS tax data to identify neighborhoods that boost the long-term earnings of young adults, AND if more housing is built in these areas, then the Abundance Agenda scales up and reduces urban poverty. Intuitively, think of my childhood zip code (Scarsdale zipcode 10583). It is primarily zoned for single-family homes and features excellent schools. The rules when I was a kid prohibited renters from living there. These rules allowed this famous public school to have high property tax revenue per pupil and it self-selected parents who were committed to their children receiving an excellent education.

As I wrote about in this prior Substack, the progressive Abundance agenda sidesteps the human capital agenda. It is silent on the role of the family and public schools in creating flourishing young people. It focuses on the physical construction of housing, green power, and public transit in creating a thriving nation. I have argued that the authors choose this focus in part to absolve public sector teacher unions from blame for our millions of struggling young people.

Point #3 The entire field of urban economics devotes ample attention to the role that “place” plays in shaping our lives. If someone spends time in Beverly Hills, or goes to Harvard or works on Wall Street, how does this time in these places shape your worldview, your skills, and your tastes and talents? Since people are not randomly assigned to places, disentangling selection effects from treatment effects is a very challenging statistical task. Intuitively, LeBron James lives in Brentwood with his young children. When they succeed in later life, how much of their success is due to the fact that they grew up in Brentwood? How much is due to their parents’ efforts?

The Chetty Team has an ingenious strategy of using variation within families in the years that different children spend in good and bad neighborhoods. Intuitively, the younger child spends more time in the new neighborhood but this raises a new issue. I sent the following paragraph of an email to a friend of mine.

So note the challenge in disentangling family dynamics (the father moving out) from the treatment effect of the younger child now growing up in a tougher area (featuring cheaper rents).

Point #4 The co-authored Heckman piece makes me think about why do New York Times reading intellectuals have such a deep desire to embrace the “power of place”? What is so seductive about this hypothesis for offering the magic bullet for reducing poverty?

A simple answer is that migration is a relatively low touch strategy. Construction unions and urban politicians are eager for there to be a downtown boom and a Federal scaling up of “move to opportunity” creates a set of vested interest groups with a stake in pouring new concrete within their Blue City borders using HUD financed federal $ transfers. Real estate developers seeking to build new housing in Blue Cities recognize that they will be asked to set aside a significant fraction of the new housing for below-market-rate tenants. Grok tells me that 75% of MTO voucher recipients use them in the Center city.

A more troubling answer returns to themes in the 1965 Moynihan Report.

Without blaming the victim, Moynihan’s ideas continue to resonate to this day. Parents have private information about how they raise their children. Many poor kids grow up with just a single parent in the household. New parents are often inexperienced and unsure of what they are doing. Most poor children spend more time with their mother than with their peers at school or neighbors. What can society offer poor mothers to help them to thrive in their own lives and to help them to equip their children to flourish? Is nudging the household to move to a better area, the best use of funds? What are alternative ways that such $ could be used to foster the development of disadvantaged children? Heckman emphasizes targeted pre-K investment for disadvantaged kids. When he was Mayor of NYC, Bill DeBlasio enacted pre-K for all. That’s not a targeted program as many parents would pay for pre-K if the Government doesn’t provide it for them.

Point #5 Neither the Chetty work nor this Heckman OP-ED discuss how destination communities are affected by welcoming relatively poor children. Is it the case that adding one “Bad Apple” to a school or a peer group disrupts education for other incumbent children? Let me be clear here, I am not saying that every poor kid is a troublemaker. Instead, I am claiming that many parents in richer communities will engage in a type of statistical discrimination and will discourage their children from interacting with these kids. This is especially likely when kids reach puberty.

Suppose that Chetty is correct that certain neighborhoods offer significant upward mobility opportunities for poor kids. If incumbent neighbors in these areas worry about negative peer effects for their kids, then they will block the scaling up of these voucher programs and a type of 1960s opposition to busing will emerge again.

In Contrast, Heckman’s policy proposal of focusing on improving parenting is scalable. There are no incumbent interest groups that would oppose investing in helping parents become better parents. There is a question of how much $ to invest in this endeavor. Heckman emphasizes that upfront investments in young children’s skills reduces ex-post fiscal challenges related to later life crime, health problems, unemployment and disability and welfare payments.

This is a very important policy debate with high stakes for poor people and it has implications for modern economics. As Economics takes a step towards data science, there is a desire to generate clean “causal effect” estimates that can be explained to New York Times reporters and Congressional aides.

For those who want to learn more about how Heckman’s team studies the interplay between parental investments and neighborhood choice, take a look at this recent Denmark paper.

"In Contrast, Heckman’s policy proposal of focusing on improving parenting is scalable. There are no incumbent interest groups that would oppose investing in helping parents become better parents. "

But what do you make of

1) Government scale-ups (Head Start, Tennessee, Georgia) of pilot or small/well-run Pre-K programs (Perry, Abecedarian) have much smaller (albeit still positive) treatment effects. The MVPF for public programs appears to be ~2 (https://policyimpacts.org/policy-impacts-library/pre-school-untargeted-programs/), which is not bad, but certainly not pays for itself or Perry territory.

a) An obvious mechanism is that the supply of good teachers is highly constrained, and the more you scale, the worse the marginal teacher and the smaller the average treatment effect.

2) Subsidized Pre-K requires higher taxes and taxes are annoyingly hard to raise in America, especially if it's for "somebody else's" children

Regardless of its effect on poverty, it make sense to remove obstacles for property owners and developers to increase the value of urban real estate.