China’s EV battery fires test the limits of layout-led safety

Battery cell layout can reduce risk, but it cannot compensate for deeper engineering and integration failures.

Ni Tao is IE’s columnist, giving exclusive insight into China’s technology and engineering ecosystem. His monthly Inside China column explores the issues that shape discussions and understanding about Chinese innovation, providing fresh perspectives not found elsewhere.

In 2025, China’s leading electric vehicle (EV) producer, Xiaomi Auto, went through a rollercoaster ride.

Up until March, thanks to the tremendous success of the Su7 sedan, Xiaomi had briefly reached the pinnacle of public attention. A series of marketing stunts aimed at demonstrating the safety of its vehicles and battery systems also brought the company huge exposure.

For instance, founder and CEO Lei Jun once dropped a watermelon coated with a “bulletproof layer” from the sixth floor, and it remained intact. Lei explained that the coating was applied to the bottom of the battery pack in the Su7 Ultra, the premium version of the Su7, to protect the cells in the event of a grounding incident.

Earlier, when the Su7 was launched, Lei also mentioned that the battery cells, developed in cooperation with CATL, were mounted vertically, downward-facing.

This innovative setup aimed to direct flames and toxic gases downward, rather than upward. As a result, it could maximize occupant safety in the event of collisions, crushes, or punctures, he said.

For a time, it seemed that battery safety, the EV industry’s long-standing scourge, had been addressed once and for all.

Shattered promises

However, the company’s safety promises were shattered by two fatal collisions in March and October, both involving the Su7. In these accidents, the car batteries quickly caught fire upon impact, and four occupants trapped inside the vehicles were burned to death.

Later in November, in a separate accident, a Mega, a luxury multi-purpose van from EV maker Li Auto, spontaneously caught fire while driving in Shanghai. The fact that the car had not been involved in a collision further intensified public concern about EV battery safety.

To be fair, in recent years, the number of reported EV fires caused by cell defects, battery management system (BMS) failures, or poor welds has fallen significantly, reflecting improvements in overall battery safety.

Nevertheless, sporadic tragedies remind us that the Achilles’ heel of EVs remains cell quality, engineering structure, thermal management, and battery layout decisions, which are increasingly linked to integrated vehicle structures.

Until solid-state batteries achieve a genuine technological breakthrough, lithium-ion cells will continue to dominate EV applications, with fire risk mitigated but not entirely eliminated.

While their energy densities differ, the production standards, manufacturing processes, and maintenance practices for lithium iron phosphate (LFP) and ternary lithium cells have largely stabilized.

Currently, Chinese OEMs are fixated on how cells are arranged—vertically (upright or inverted) or horizontally (lying flat). Aside from Tesla’s cylindrical cells and some Japanese soft-pack solutions, most domestic automakers use prismatic cells, and the majority mount them vertically.

In this design, the cells’ positive and negative terminals face upward or are connected through specialized arrangements to form modules, which are then integrated into the battery pack.

Upright orientation

In traditional upright orientation, cells are placed normally, with polarity aligned to the battery pack. This is one of the most conventional and stable arrangements adopted by most domestic automakers.

Upright orientation has several notable advantages. Aligning the electrolyte with gravity helps prevent local pooling or uneven membrane stress, reducing the risk of short circuits and thermal runaway.

Internal pressures are more evenly distributed, promoting cycle life and consistency. Vent placement is safer, directing heat and gases along designed channels rather than randomly.

Overall, upright cells are easier to optimize for thermal management and structural reliability, and the supply chain and maintenance processes are mature and stable.

Its drawbacks are notable as well. Compared with integrated battery structures such as cell-to-pack (CTP), cell-to-body (CTB), or cell-to-chassis (CTC), traditional upright designs require more casing and module components, reducing volume efficiency.

Lower space utilization can limit energy density per unit volume, affecting range and battery capacity—simply put, fewer cells mean shorter driving range. Additionally, in extreme cases, venting upward can direct flames and toxic gases into the cabin, posing risks to occupants.

Inverted cells

The biggest proponent of inverted cell technology is undoubtedly Xiaomi. According to the company, its inverted-cell plus CTB design significantly improves battery-pack space utilization, achieving 77.8 percent volume efficiency, enabling a higher range, and enhancing safety.

Inverted cells optimize vertical space by combining the top insulation area and the bottom buffer space into a single layer, freeing an additional 5–10 mm. The vent valves are also inverted, directing gases downward in case of thermal runaway.

This design, called “thermal-electric separation,” helps release high-pressure, high-temperature gases safely away from the cabin. Theoretically, inverted orientation can also fit more cells into the same pack volume, lowering costs.

Research shows that inverting battery cells introduces new challenges: the liquid electrolyte can pool near the cell cap, leaving the terminals submerged for long periods, which may cause corrosion, metal ion leaching, and potentially affect cycle life and safety.

To counter this, Xiaomi and CATL developed a specialized electrolyte for the inverted layout, reinforced cell protection with multi-layer insulation, and high-voltage shielding. The two companies also redesigned the bottom venting channels of the batteries to safely expel hot gases downward during thermal runaway, thereby protecting the passenger cabin.

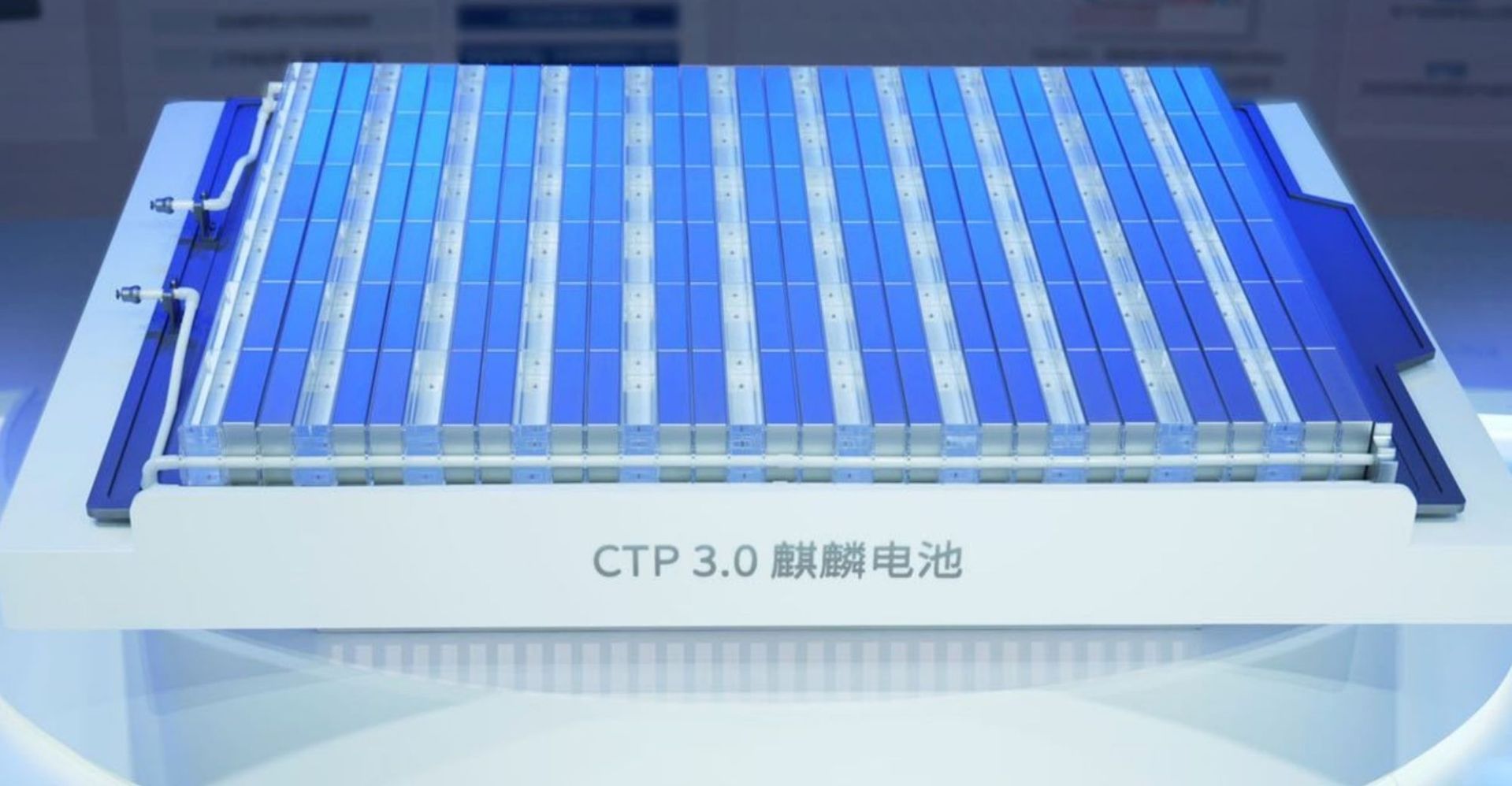

This technology, pioneered by CATL’s Kirin battery, which first came out in 2022, was heavily touted by Xiaomi. However, given the tragic incidents, its real-world safety performance is questionable, to say the least.

Horizontal mode

The best representatives of the flat-cell technology are BYD’s Blade Battery and SAIC’s Rubik’s Cube Battery. Cells are laid out along their long edges rather than standing upright, as is common in highly integrated car designs like CTP, CTB, and CTC

The goals are essentially to reduce pack height, improve space utilization, and increase design freedom. Benefits include lower vehicle floors, more cabin space, and lower center of gravity, enhancing handling—especially for sedans and performance models.

For example, SAIC MG, a sports car brand, has noted that horizontal orientation makes the pack thinner, improving space, maximizing driving dynamics, and even enabling battery swapping.

BYD’s Blade Battery represents another major horizontal setup: its long and thin LFP cells arranged like “blades” across the pack. Instead of simply turning a standard prismatic cell sideways, these cells are designed to lie flat and directly contribute to structural support, making them naturally suited for module-less and CTB designs, reducing pack height and improving both space efficiency and safety.

Flat-cell advantages include module-less packs, more cells per volume, and higher system energy density. Thermal management also benefits: large side surfaces can contact cooling plates for efficient heat dissipation, especially in liquid-cooled packs.

Constraints are also clear, though: horizontal cells experience lateral stress and thermal expansion, which can cause uneven swelling and local stress. Venting is more complex, as gases and flames do not naturally vent upward, requiring ingeniously engineered channels and insulation structures. In a word, flat-cell designs demand higher engineering capability to ensure safety.

Integration trends

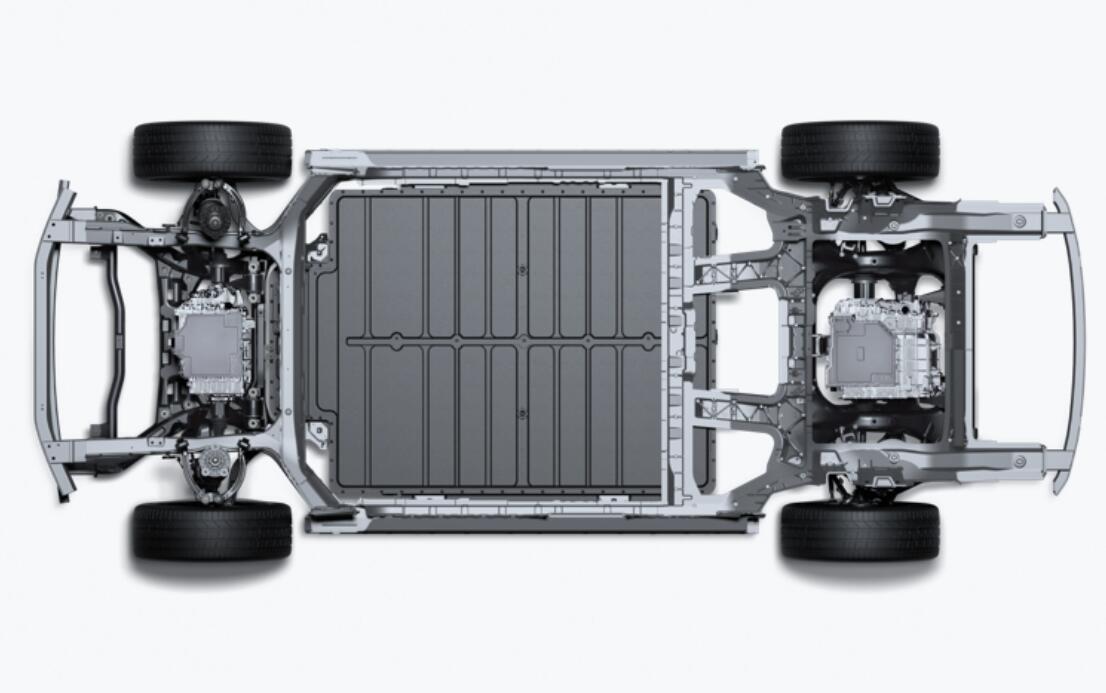

Cell layout is increasingly determined by vehicle integration. In the CTP approach, modules are eliminated, allowing the cells to form the pack directly. This improves space utilization and energy density while keeping the battery largely independent.

CTB goes a step further by integrating the battery into the vehicle floor, enabling the cells to contribute to the car’s structural rigidity while optimizing space and overall performance.

The highest level of integration is CTC, where the cells become part of the chassis itself. This reduces the number of components and overall weight but places the greatest demands on vehicle and battery engineering.

Regardless of which approach is favored, one thing is clear: in recent years, cells have evolved from mere functional components to structural elements.

Larger, flatter, or longer cells reduce module count, improve volume efficiency, and can withstand bending and compression, directly participating in pack and vehicle structural loads.

Safety and thermal management are now closely coupled with architectural design, including controlled venting and optimized heat pathways.

Manufacturing consistency is increasingly critical. As module-less and integrated pack designs become common, variations in single-cell performance are amplified, driving upgrades in materials, precision, and lifespan consistency. Designing cells for specific structures is gradually replacing generic cells as the industry standard.

In this context, there is no absolute “best” orientation. Whether vertical, inverted, or horizontal, cell layout is a balance of several factors; each approach suits specific vehicle architectures, platforms, and cost targets.

Success depends on finding the right balance between space efficiency, battery safety, and engineering feasibility, a balance both automakers and battery manufacturers must carefully navigate.

Recommended Articles

Ni Tao worked with state-owned Chinese media for over a decade before he decided to quit and venture down the rabbit hole of mass communication and part-time teaching. Toward the end of his stint as a journalist, he developed a keen interest in China's booming tech ecosystem. Since then, he has been an avid follower of news from sectors like robotics, AI, autonomous driving, intelligent hardware, and eVTOL. When he's not writing, you can expect him to be on his beloved Yanagisawa saxophones, trying to play some jazz riffs, often in vain and occasionally against the protests of an angry neighbor.

- 1US: Last Energy raises funds to mass produce steel-encased micro nuclear reactors

- 2China: World’s largest-diameter boring machine reaches 6-mile tunneling milestone

- 3Sweden unveils Europe's first car park constructed using recycled turbine blades

- 4China's ultra-hot heat pump could turn sunlight into 2,372°F thermal power for industries

- 5Solar storm could cripple Elon Musk's Starlink satellites, causing orbital chaos