The space-based heat maps changing how engineers fix cities

Satellites reveal the hottest city blocks, and engineers use that data to cool streets with reflective pavement, trees, and smarter design.

Cities worldwide are finally able to see their urban heat islands from above—and engineers are racing to turn those thermal pixels into cooler streets and safer neighborhoods.

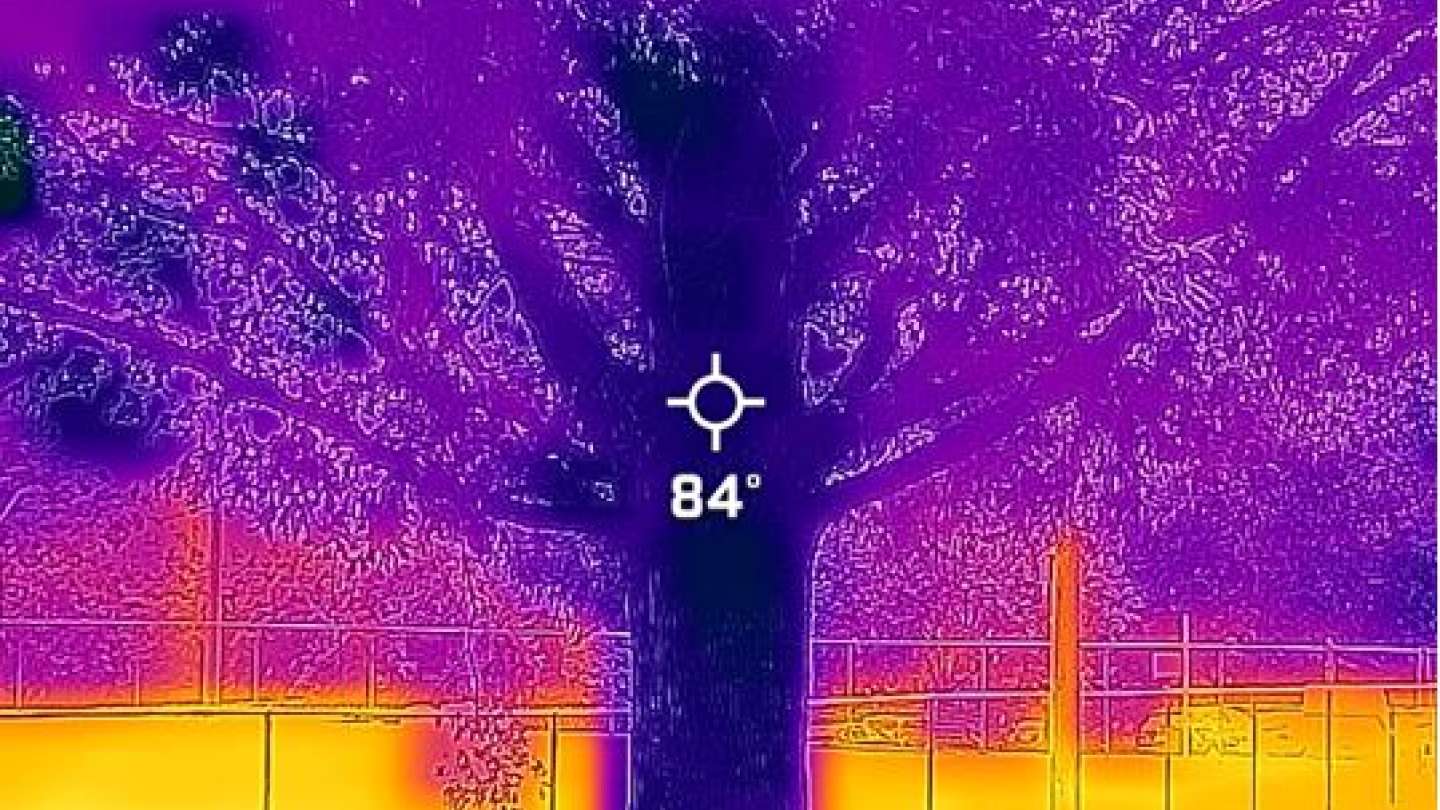

Satellite thermal sensors can now reveal which blocks bake hottest after sundown, and city planners are using this data to reprioritize projects. As Los Angeles Bureau of Street Services Chief Sustainability Officer Greg Spotts notes, “all of our hardscape – our transportation infrastructure – is radiating heat into our neighborhoods even at 4 in the morning,” a phenomenon that is “detectable from space”.

In practice, that means dark asphalt freeways, parking lots, and rooftops show up as blazing red on high‑resolution thermal maps. Cities from Los Angeles to Chicago now combine these satellite maps with on‑the‑ground data to target the worst hotspots.

In Prince George’s County, Maryland, NASA scientists used Landsat images to find that the county landfill had become the “largest area of intensifying/persistent/historical warming” on public land—and city engineers have since shifted mitigation plans (adding trees, bioswales, reflective covers) to cool that site first.

New space sensors are only making this easier. NASA’s ECOSTRESS instrument on the ISS, for example, collected imagery of Los Angeles in 2018, showing surface‐temperature variations at the sub‑block scale. It measured midday temperatures up to 147.3°F on a hot August afternoon—”hot enough to fry an egg” on a parking lot—and traced how roofs and roads cool off overnight.

Meanwhile, new commercial satellites are coming online: UK-based SatVu’s HotSat constellation will launch in 2025 to deliver WorldView‑style thermal imagery. Those satellites are aimed at climate uses from urban heat resilience to economic monitoring, offering engineers fresh data on exactly where cities are hottest.

The moment a thermal map changed a city’s plan

Thermal maps from space can immediately flip engineers’ to‑do lists. In Los Angeles, satellite and aerial data showed intense heat radiating from neighborhood streets, not just highways.

LA’s urban cooling program, therefore, paired reflective street sealants with massive tree planting. In 2023, the city’s pilot project sealed 200 blocks of residential streets with a high‑albedo coating and planted 2,000 new trees in high‑exposure neighborhoods. In each pilot block, treated streets ran about 10°F cooler than adjacent untreated streets, a dramatic change confirmed by roadside sensors.

Philadelphia had a similar experience. City sustainability engineers found that surface temperatures in parts of North and West Philadelphia routinely ran 20°F hotter than in leafy areas.

In response, the city’s Office of Sustainability is testing a reflective “CoolSeal” pavement on two road sections in the heat‑vulnerable Hunting Park neighborhood. “We just want to make residents feel cool and comfortable in their neighborhoods,” said Andrew Dodd, program manager for heat resilience in Philadelphia. His team enlisted the University of Pennsylvania to instrument the test patches with sensors, studying both temperature effects and durability. Philadelphia’s pilot is one of the first to evaluate cool pavement in a humid mid‑Atlantic climate.

If successful, the city hopes to roll out cool paving more widely; already, city maps show where cool roofing and street coatings could yield the biggest air‑temperature drops.

Cities are finding that even small hardware changes can yield outsized impacts when they are data‑driven. In Phoenix, researchers at Arizona State University teamed with the city and 3M to apply a thin reflective film (“cool roof” coating) to a pilot structure at a downtown “Safe Outdoor Space” for homeless residents. By training infrared sensors, the engineers predict that this coating could shave several degrees off the rooftop’s thermal load. ASU field technician Eli Martin explains the motivation:

“We’ve all seen… the impact that extreme heat has on marginalized communities. So, being able to make sure that we’re protecting everybody from the heat in an equitable manner is really, really important as we get hotter and hotter”. Early results are encouraging: in past projects, Martin notes the film has cut mean radiant temperature under a canopy by ~3 °C (≈5.4 °F).

From maps to actions: Trees, reflective surfaces, and more

Armed with a thermal map, city engineers have a toolkit of proven cooling strategies—from planting to paving. The simplest is shade. Strategically adding tree canopy or green roofs can slash local temperatures dramatically. In Portland, community heat mapping showed that forested parks and vegetative buffers can spill significant cooling into neighboring blocks.

One study concluded that “adding vegetation, using reflective material on hard surfaces, and installing green roofs on buildings can cool urban heat islands as much as 25 degrees [Fahrenheit] in some spots”. UCLA urban planning professor V. Kelly Turner stresses that shade is by far the most effective way to cool people outdoors, because it blocks direct sun. In practice, engineers combine both: Los Angeles’ program paired cool pavement with thousands of new trees to maximize cooling synergy.

Reflective materials are another key lever. Light‐colored sealants, paints, or pavers can bounce back much of the sun’s energy before it heats up the city. Asphalt normally absorbs ~90% of solar radiation, but a thin light-colored coating (only ~100 µm thick) can reflect ~40% of that energy.

In Los Angeles’ pilot, treated streets registered 10°F cooler surfaces than untreated streets during heat waves. In Phoenix, coated pavement was up to 5°F cooler than regular asphalt in testing. Crucially, these changes require relatively modest investment: Phoenix’s cool sealant costs about $5.00 per yd² versus $4.40 for standard pavement oil, and one estimate suggests that even a 1°F drop citywide could save $15 million per year in reduced air-conditioning costs.

Modern engineering now even leverages data modeling to optimize interventions. Google recently piloted an AI‑driven tool in 14 U.S. cities that predicts how tree‑planting or cool roofs would affect land-surface temperatures. This kind of spatial analysis—combining satellite thermal layers with demographic data—helps engineers perform cost-benefit trade-offs.

For instance, a Google-backed analysis in Phoenix and LA indicates that reflective pavements can lower ambient air temperatures by up to 3.5°Fduring heat events. (California’s Climate Resolve team confirmed those model results: Pacoima residents reported feeling a noticeably cooler breeze after 700,000 ft² of neighborhood asphalt was painted with white reflective coating.)

These interventions are most effective when guided by data. Satellites and models flag the hottest alleys and buildings, letting engineers deploy solutions where they matter most. In practice, that means mirroring the thermal map in the field.

Los Angeles now focuses its tree-planting and cool pavement pilot on the hottest, least leafy districts identified by imagery and LIDAR canopy maps. Raleigh, North Carolina, used its community-collected heat map to decide exactly which low-income blocks needed reflective street treatments. In each case, engineers opined that data created science-based criteria to inform and prioritize projects rather than instincts alone.

Case studies: Cooling the streets, one tile at a time

One of the most ambitious cooling retrofits is Los Angeles’s “Next Phase Urban Cooling” program. Guided by satellite maps and canopy data, LA public works crews have applied reflective sealant to over 200 neighborhood blocks (totaling hundreds of miles of street) in historically overheated, low-income areas. Engineers selected concrete mixes and sealant chemistries to maximize reflectance.

On treated streets, daytime surface readings were up to 10°F cooler than on untreated streets nearby. Overnight, even at 4 a.m., the treated asphalt was cooler—a validation of Spotts’s remark that the heat was once “detectable from space”.

LA’s program didn’t rely solely on thermal maps, however. The city also deployed airborne LIDAR and drone surveys, and cross-referenced historic satellite data to ensure they were targeting the highest-exposure microclimates. These engineering analyses were paired with extensive public outreach via neighborhood councils.

The project’s success has hinged on integrating high‑tech mapping with on‑the‑ground knowledge—for instance, city crews avoided “cool pavement” on sections exposed to heavy truck traffic (where durability was a concern) and instead focused on quiet side streets near parks and homes. Project engineers report that the initial cost premium was modest (about $0.60 more per yd² than regular asphalt sealant), while the cooling payoff is substantial. A city analysis projects that even lowering average street‑level temperature by 1°F could save L.A. residents tens of millions of dollars per year in reduced cooling energy and health costs.

Meanwhile, in Raleigh/Durham and nearby North Carolina communities, the emphasis was on community‑driven data and equity. In the summer of 2021, more than 250 volunteers helped collect nearly 100,000 temperature points across Raleigh and Durham, all guided by NOAA funding and CAPA’s technical support.

That campaign revealed sharp disparities: one affluent, leafy neighborhood stayed near 90°F in the afternoon, while an adjacent asphalt-heavy district rose to nearly 100°F—a 9.6°F gap within the same city block. These “hyperlocal” findings galvanized action. The Raleigh City Council used the data to prioritize a $4 million pilot that coated roadways in the hottest census tracts with reflective material (an approach predicted to cut nearby air temperatures by ~7°F).

And in Durham, seeing their own community in red on the map led local schools and nonprofit “green teams” to apply for grants to plant trees and create shaded bus stops in those neighborhoods.

Funding and coordination: Lessons for other cities

The urban heat challenge has spurred an unprecedented coalition of public and private funders. In the U.S., the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act earmarked $150 million for NOAA to tackle extreme heat (among other climate risks). NOAA’s new Center for Collaborative Heat Monitoring is now accepting applications: communities can win $10,000 grants and technical mentorship to run their own heat-mapping campaigns. These small grants can cover sensor kits, community workshops, or temporary staff—precisely the capacity many cities lacked.

Separately, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Hazard Mitigation programs are trickling funding for “cooling infrastructure” (street trees, cool roof incentives, etc.) into city budgets. NASA too has made heat resilience a priority: as a July 2025 Frontiers paper reports, NASA’s collaboration with Prince George’s County provides free satellite data and modeling to local planners, bridging the gap between science and practitioners.

On the philanthropic side, global coalitions are forming. The new C40 Cool Cities Accelerator unites dozens of cities (Austin, Nairobi, London, Manila, etc.) with backing from the Rockefeller and ClimateWorks Foundations.

ClimateWorks Director Jessica Brown notes that the initiative has already marshaled $50 million in adaptation funding specifically for communities on the front lines of heat. These funds are aimed at training “chief heat officers” and cross‑agency teams, deploying early warning systems, and embedding equitable cooling into city design.

These lessons suggest that successful programs combine data, dollars, and people. On the data side, cities should tap all available sources—from free Landsat/ECOSTRESS products to subscription platforms like Descartes Labs or SatVu—and layer thermal maps with vulnerability indices.

Partnerships with universities or NASA/NOAA can bring expertise and modeling power. For funding, cities should apply for federal resilience grants (NOAA, HUD, FEMA) and look for state/climate funds for green infrastructure. The UK Space Agency’s recent investment in SatVu, for instance, signals new channels for urban planners to acquire satellite analytics. Finally, coordination among city departments and with community groups is essential to translate pixels into people-centered solutions.

As one heat resilience advocate summarized, “These maps can and should inform hyper-local strategies to keep people safe.” The payoff is both technical and human. In every case, engineers report that even a few degrees of surface cooling—on a hot road or rooftop—can noticeably improve public comfort and safety. Cities that combine those insights with reflective materials, green corridors, and grassroots involvement are lighting the way toward cooler, more equitable urban futures.

Recommended Articles

Srishti started out as an editor for academic journal articles before switching to reportage. With a keen interest in all things science, Srishti is particularly drawn to beats covering medicine, sustainable architecture, gene studies, and bioengineering. When she isn't elbows-deep in research for her next feature, Srishti enjoys reading contemporary fiction and chasing after her cats.

- 1US scientists fix EV batteries' capacity degradation issue, boost cells' lifespan

- 2US firm plans 50,000-strong humanoid robot army for defense, industrial work

- 3Google's quantum processor could perform 1,000 times better with Princeton's new qubit

- 4US: Last Energy raises funds to mass produce steel-encased micro nuclear reactors

- 5Pentagon study shows how China could use hypersonic arsenal to defeat US aircraft carriers against US carriers