The brain may be the blueprint for the next computing frontier

Engineers are turning to neuromorphic chips to bring fast, efficient, and local intelligence to the edge, not by scaling AI, but by redesigning how machines think.

Neuromorphic computing, or hardware modeled on the brain’s neurons and spikes, is rapidly moving from research labs into real-world engineering. In this edge-computing era, companies and researchers are building “brain-like” chips that process data only when events occur. The result? Dramatically higher energy efficiency and much lower latency than traditional GPUs and CPUs.

Spiking neural networks (SNNs) are radically different from conventional AI. Inspired by the brain’s event-driven “spiking” behavior, SNNs use asynchronous spikes instead of fixed numeric activations.

As one recent review explains, “[Deep neural networks] offer high accuracy and easy-to-use tools but are computationally intensive and consume significant power. SNNs utilize bio-inspired, event-driven architectures that can be significantly more energy-efficient, but they rely on less mature training tools.”

This brain-like sparseness gives huge power savings. Intel reports that Loihi-based neuromorphic chips can perform AI inference and optimization using 100 times less energy, at speeds 50 times faster, than conventional CPU/GPU systems. IBM’s TrueNorth chip achieved 400 billion operations per second per watt—an energy efficiency rivaled by no traditional processor.

These gains come with trade-offs. SNNs tend to be less mature in accuracy and tooling. As one review notes, traditional DNNs still win on accuracy and ease of use, whereas SNNs “can be significantly more energy-efficient” but require novel training methods. Researchers are closing this gap, but for now, spiking AI often slightly lags behind standard AI in raw accuracy.

Brain-inspired SNNs process data in milliseconds with microjoules, not seconds with joules. Their event-driven “fire only when needed” paradigm delivers drastically lower latency and power, even if specialized algorithms and hardware are needed.

recurrent networks with 128 synapses per neuron, average, and three different

average firing rates. (Source: IEEE)

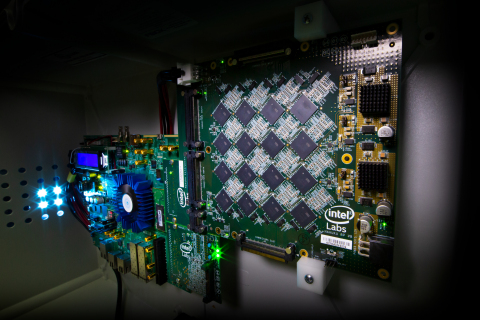

The global race: From Loihi to Darwin Monkey

Tech giants and nation-states are investing heavily in neuromorphic chips. In the US, Intel and IBM have led the way: IBM’s 2014 TrueNorth featured 1 million neurons, 256 million synapses, and drew just 65 mW while performing 58 Giga-synaptic ops/s. Intel’s labs followed with Loihi, Loihi 2, and large systems, such as Pohoiki Beach (8 million neurons) and Hala Point (1.15 billion neurons). Intel claims those prototypes run 50× faster with 100× less energy than GPUs, and that packing 1152 Loihi2 chips into its Hala Point allowed “orders of magnitude gains in speed and efficiency”. BrainChip (USA/Canada) and startups like SynSense (Switzerland) are also pushing neuromorphic IP. BrainChip’s fully digital Akida SNN core is designed for edge AI in cars and cameras.

On the other side, China is surging. Beijing’s tech plans pour tens of billions into AI hardware, with neuromorphic chips serving as a flagship. For example, China’s Darwin Monkey project built a rack-scale neuromorphic computer with over 2 billion neurons and 100 billion synapses, yet it draws only ~2,000 W of power. This system (“Wukong”) uses 960 custom neurosynaptic chips across 15 racks, rivaling Intel’s Hala Point in scale but at one-tenth the power. China’s government-backed initiatives complement this: reports cite up to $150 billion pledged to indigenous AI and chip R&D.

Intel, IBM, and others are closely monitoring these developments. Intel’s Loihi and Loihi2 chips each model 1–2 million neurons with up to hundreds of millions of synapses, while TrueNorth’s million neurons operate with event-driven parallelism—figures dwarfed by the Darwin project’s billions. Yet, each approach offers unique strengths. IBM recently committed ~$30 million to a next-gen neuromorphic R&D effort (“NorthPole”). EU and Japan also fund neuromorphic research (e.g., Japan’s AiMOS project).

The global race pits Western chip-makers and startups against Chinese state-backed ventures. Analysts predict neuromorphic will spread across all edge AI niches. With governments and industry investing heavily in brain-like processors, this is a leading front in the Industry 4.0 semiconductor arms race.

Industrial applications: Autonomous robots & IoT with millisecond brains

Neuromorphic chips are not just lab curiosities—real systems are already demonstrating ultra-fast, low-power industrial performance. Consider autonomous drones and robots: at TU Delft, researchers built a fully neuromorphic flying drone. Its event-camera input and control network ran on an Intel Loihi chip on board, achieving processing speeds up to 64 times higher than a GPU, while consuming approximately three times less energy. As Neuroscience News highlighted, “the drone’s deep neural network processes data up to 64 times faster and consumes three times less energy than when running on a GPU.” These efficiency gains translate to sub-millisecond reaction times for obstacle avoidance and control, which are crucial for agile robots.

Real-time vision and sensing are another strong suit. Event cameras and spiking processors excel at high-speed inspection. In manufacturing trials, neuromorphic vision counted parts on a conveyor and detected weld defects far faster than conventional cameras.

For example, one study used an event camera to count corn kernels on a fast-moving feeder line, demonstrating accurate item counting in a production setting. Others placed event cameras on welding robots, which allowed them to “visualize welding dynamics with superior temporal fidelity” and flag anomalies in real-time. In vibration-based monitoring, an event-based stereo system tracked mechanical vibrations with the same precision as costly laser vibrometers. In practice, these demos show neuromorphic AI achieving millisecond-range sensing and decision loops.

Edge IoT devices also benefit from maintenance and monitoring. A recent German case study developed an SNN on Loihi for pump vibration data, achieving 97% fault-detection accuracy with nearly zero false negatives. This was accomplished using only 0.0032 J per inference on Loihi, compared to 11.3 J on an x86 CPU. That’s a 1,000× power reduction for real-time anomaly detection at the sensor. Similarly, simple IoT nodes, such as smart cameras and microphones, can offload heavy AI tasks to tiny neuromorphic chips. BrainChip reports that its Akida SNNs can recognize voice commands (e.g., “Hey Mercedes”) in a car using just milliseconds and tens of µJ, versus hundreds of milliseconds and µJ on traditional controllers.

Neuromorphics and the energy crisis

The technical payoff highlighted above suggests a market explosion. Analysts project that the edge-AI and IoT markets will rapidly embrace neuromorphic hardware to solve looming power and latency bottlenecks. For one, the number of IoT “things” is skyrocketing: forecasts suggest about 29 billion connected devices by 2027, driven by smart cities, manufacturing, and consumer wearables. With each device requiring tiny, efficient AI, industry experts predict that on-device intelligence will become the dominant approach. Gartner analysts have suggested that the majority of new IoT products will incorporate local AI by the late 2020s, and ABI Research expects neuromorphic chips to pervade edge applications.

Market data backs this up. A report estimates the neuromorphic computing market will swell from ~$28.5 million in 2024 to $1.32 billion by 2030 (an 89 percent CAGR). Similarly, Fortune Business Insights notes that “AI PC” shipments (a proxy for edge AI devices) will increase from approximately 50 million units in 2024 to over 167 million by 2027.

Market researchers highlight neuromorphic designs for their ultra-low-power benefits. One report highlights how these chips “minimize energy-intensive data movement,” a critical boon for battery-powered IoT devices.

Executives agree that the tide is rising. Mercedes-Benz, for example, is exploring neuromorphic AI in cars, saying how it “could make AI calculations significantly more energy-efficient and faster”. The Mercedes R&D team reports that a neuromorphic vision system could reduce autonomous-driving compute energy by ~90% compared to today’s stack.

Startups like SynSense and BrainChip claim hundreds of millions in private funding, and analysts say the global chip giants (Qualcomm, HPE, etc.) are rapidly adding neuromorphic to their roadmaps. In summary, with tens of billions of dollars projected for AI edge spending, analysts foresee that a majority of new IoT devices will run on brain-inspired chips within a few years. The oft-repeated figure is “70 percent of IoT by 2027,” which aligns with IoT growth forecasts, meaning neuromorphic could power edge AI in most devices soon.

In summary, neuromorphic edge computing is transitioning from theory to practice in Industry 4.0. From autonomous drones to smart factories, brain-inspired chips are delivering milliseconds of response and milliwatts of power consumption.

As one Intel researcher put it, these systems represent an “order of magnitude” leap in efficiency. With governments and companies investing billions in this technology, neuromorphic hardware is poised to drive the next generation of industrial IoT, robotics, and intelligent automation.

Recommended Articles

Srishti started out as an editor for academic journal articles before switching to reportage. With a keen interest in all things science, Srishti is particularly drawn to beats covering medicine, sustainable architecture, gene studies, and bioengineering. When she isn't elbows-deep in research for her next feature, Srishti enjoys reading contemporary fiction and chasing after her cats.

- 1Allag-E: Interceptor aircraft can hunt and kill drones flying at 124 mph like an eagle

- 2Modernized nuclear warheads ready for deployment on 18,750-ton US missile submarines

- 37 of the world’s most powerful tidal turbines generating megawatts under sea

- 4US firm unveils low-cost exoatmospheric interceptor to kill missiles mid-flight

- 5Sodium EV battery beats lithium in charging speed and temperature stability: Study