Where China leads and lags in humanoid joint architecture

China’s robotics ecosystem excels at rotary actuators, but its lag in high-precision planetary roller screws still limits progress toward industrial-grade humanoids.

Ni Tao is IE’s columnist, giving exclusive insight into China’s technology and engineering ecosystem. His monthly Inside China column explores the issues that shape discussions and understanding about Chinese innovation, providing fresh perspectives not found elsewhere.

In the humanoid robotics race, all eyes are on the “brain”, the embodied AI model that reasons, reacts, and adapts. But beneath the surface, a quieter battle rages over the robot’s “physique” and “cerebellum”: the actuators, screws, and gearboxes that convert thinking into movement. And far from being solved, hardware may now be the biggest bottleneck of all.

This is partly because Chinese manufacturers like Unitree and Engine AI have showcased humanoids capable of dancing, jumping, performing martial arts, and even doing somersaults at remarkably low cost. Many now assume that hardware is no longer a bottleneck. Yet the ongoing debate between proponents of rotary and linear actuators shows that hardware choices remain critical to the industry’s future.

Specifically, should humanoid robots stick with mature gear reduction solutions, or embrace emerging planetary roller screw technology?

Rotary dominance

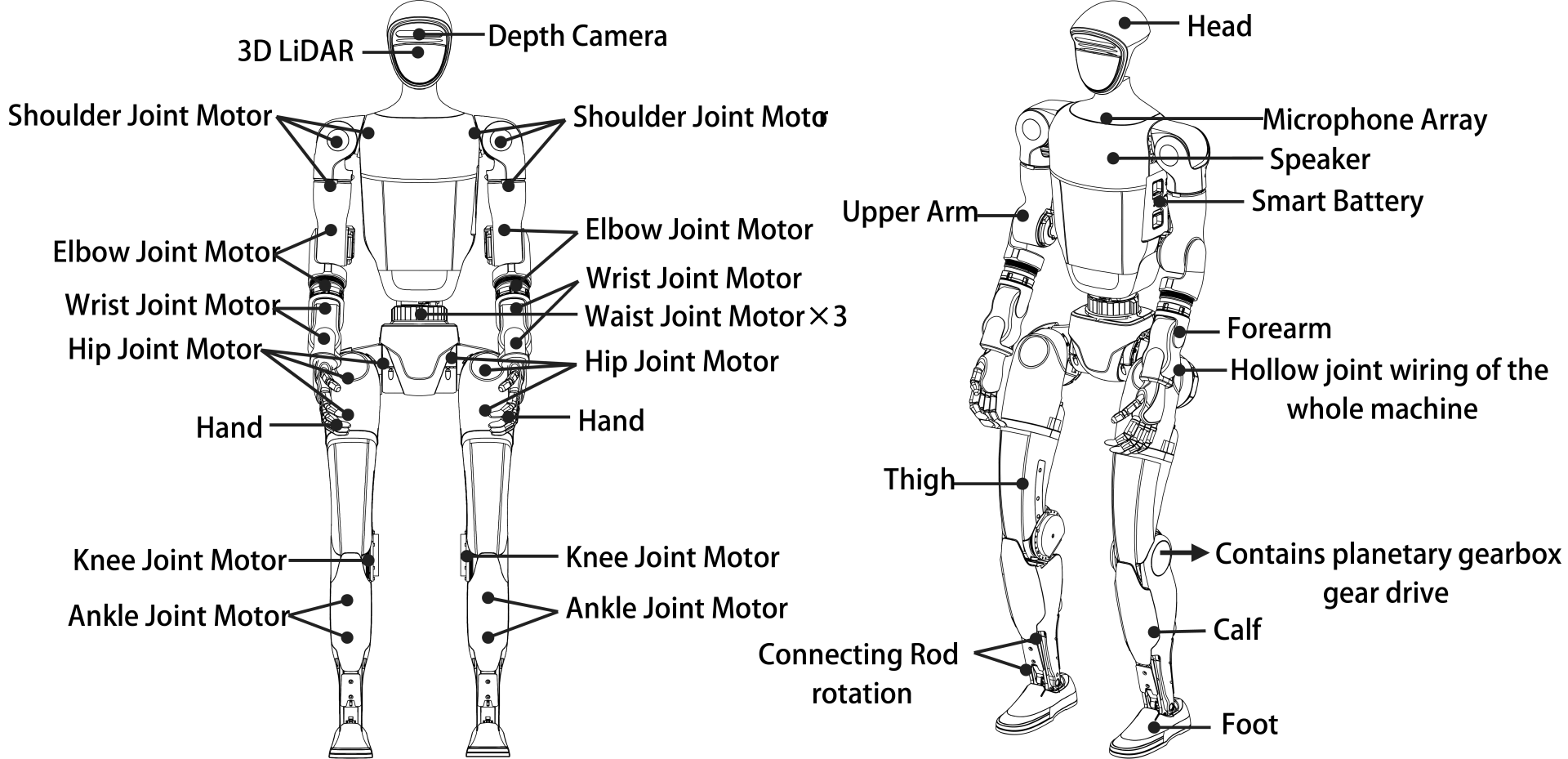

Joint modules for humanoid robots generally come in two configurations: rotary and linear actuators. Today, actuators in the waist, shoulders, and hips typically integrate motors, sensors, and encoders with reducers that convert rotational motion, such as harmonic drives and planetary gear reducers.

Planetary reducers, prized for their high rigidity, load capacity, and transmission efficiency, are usually preferred for joints requiring high torque. Harmonic drives, known for being compact, lightweight, and highly precise, are widely used in precision components such as dexterous robotic hands.

These reducers play a crucial role in rotary actuators. By multiplying the motor’s torque tens or even hundreds of times, they enable robotic joints to lift arms, bend, walk, grasp objects, and even perform acrobatics like backflips.

Thanks to their widespread use in industrial robotics and automation, rotary actuators built around RV reducers, harmonic drives, and planetary gearboxes are now highly mature and cost-efficient.

For instance, Unitree’s flagship G1 robot relies on planetary and harmonic reducers as its primary rotation-based joint mechanisms, as shown in its 3D engineering diagrams.

The linear trajectory

Although rotary actuators benefit from a robust industrial supply chain, their inherent limitations are becoming increasingly apparent. While flexible, their load-bearing capacity is modest. Most mainstream humanoid robot arms can lift only 5–10 kilograms, far short of the 50–100 kilogram loads typical in industrial settings. They also struggle with tasks requiring fine precision.

To address these limitations, several humanoid models—notably Tesla’s Optimus, Apptronik’s Apollo, and China’s Xpeng’s IRON—have adopted linear actuators. These mainly come in two types: ball screws and planetary roller screws.

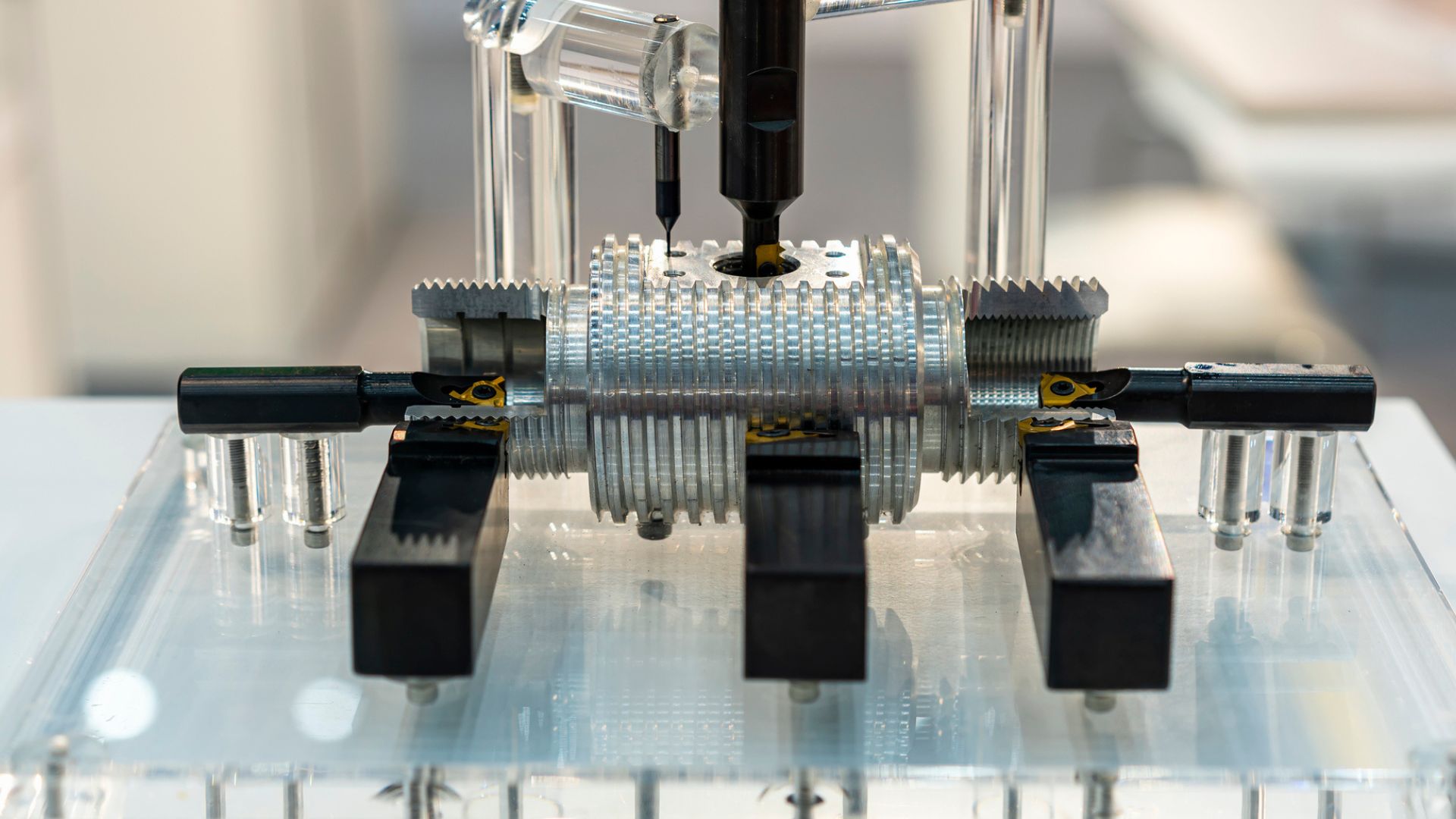

Both convert rotational motion into linear movement via a sophisticated screw mechanism. The difference lies in whether balls or rollers transfer the load between the nut and the screw shaft.

Ball screws, using recirculating ball bearings, are cost-effective and precise, providing smooth, accurate linear motion with reduced wear. Planetary roller screws, however, distribute load across multiple rolling contact surfaces, making them ideal for high-precision, high-load, and long-duration applications. They are particularly suited for impact-heavy joints such as hips, knees, and ankles, allowing the robot to withstand external forces with stability.

Public information shows Tesla’s Optimus Gen-3 uses 14 planetary roller screws: two in the upper arms, four in the forearms, four in the thighs, and four in the lower legs. Tesla primarily sources them from Switzerland’s GSA (RGTI 12.8 inverted planetary roller screw). Xpeng’s IRON reportedly uses even more screws, though the exact type—ball or planetary—has not been specified.

The ‘heavy-lifting’ screw

Compared with ball screws, planetary roller screws achieve higher precision due to their unique thread structure and rolling motion. Instead of point contact for ball screws, the rollers create line contact, distributing force more evenly and enhancing load capacity, rigidity, motion accuracy, and stability.

More importantly, planetary roller screws enable self-locking. When a robot equipped with these parts stands or walks, ground impact forces can be absorbed mechanically.

This allows the machine to maintain posture with minimal electrical power. For humanoids weighing more than 50 kilograms, where the hip, knee, and ankle joints bear the bulk of the load, rotary joints require continuous power for the robot just to stay upright.

“Robots equipped solely with rotary joints can dance and run, but they typically last only two to three hours on a single charge,” says Debo Hu, CEO of Chinese humanoid startup Kepler Robotics, which utilizes a hybrid actuator structure for its K2 Bumblebee bot. “Even standing still requires recharging after three to four hours.”

By contrast, those equipped with planetary roller screws can theoretically stand for an entire day without recharging, Hu adds.

In load-bearing performance, planetary roller screws also have a clear advantage. Their larger contact surface and more uniform stress distribution allow a screw of the same diameter to support 3–6 times the load of a ball screw—and up to 10 times in extreme cases. Their service life may be as much as 15 times longer, significantly reducing maintenance and downtime.

No clear winner

But if planetary roller screws are so advantageous, why haven’t most humanoid makers adopted them? The answer comes down to use cases.

For robots designed for highly dynamic performance—sprinting, jumping, or backflips—rotary actuators remain the practical choice. The technology is mature, the dynamic response is excellent, and it allows for fast, agile motion.

One emerging trend is that humanoids built for companionship, guiding, concierge work, home assistance, and other light-duty roles will likely become cheaper as production for rotary actuators scales.

Meanwhile, robots designed for industrial labor—lifting heavy loads and performing physically demanding tasks—are more likely to rely on linear actuators. These machines are more powerful, potentially hazardous, and therefore demand advanced AI for safe operation.

In an apparent jab at his Chinese competitors, Figure’s founder and CEO Brett Adcock said on October 17 that some companies are merely “doing theatrics with robots”—running them in an open-loop mode, teleoperating them or having them dance “like a movie set.” The real issue, he argued, isn’t manufacturing but general intelligence.

Adcock’s criticism of robotic theatrics is not without merit, though the idea that hardware manufacturing is unimportant is hard to justify.

It is also necessary to correct a common misconception: that linear actuators are only for “serious” industrial humanoids, while rotary joints suffice for “theatrical” robots. In fact, leading Chinese players such as Unitree, Agibot, and Engine AI—perhaps the very ones Adcock was alluding to—are already testing planetary roller screws in both upper and lower limb joints, albeit in limited quantities for now.

China’s advantage? Not so soon

The second barrier to wider penetration of the planetary roller screw is cost. According to Morgan Stanley, a single screw typically runs between $1,350 and $2,700. Optimus uses 14, accounting for about 19 percent of the robot’s total cost. Overall, actuators make up 56 percent of Optimus’s core component cost.

Precision planetary roller screws require thread channel errors to be kept within 3 microns—about one-twentieth the thickness of a human hair. This level of precision entails ultra-precision computer numerical control (CNC) grinding equipment. This is an area where Chinese firms have historically lagged behind Western industrial leaders like GSA and Rollvis SA.

Tesla currently sources from GSA for screws. In China, a handful of its Tier-1 auto parts suppliers—such as Tuopu Group, Seenpin, and Beite Technology—are advancing in this space, given the overlap between car and robotics transmission gear.

China’s massive supply network for automotive transmission does possess some scale and cost advantages. But contrary to some observers’ predictions, it does not, as of yet, enjoy a head start in high-precision planetary roller screws. In effect, this may well be an Achilles heel.

Screw accuracy is classified from C0 to C9 under Japanese Industrial Standards (JIS), with lower numbers denoting higher precision. Humanoid robots typically require C5 or C3 screws. For example, Tesla’s 2025 update to Optimus Gen-3 uses C3 precision ball screws in some joints, limiting lead error to 3 microns per 300 millimeters.

Meaningful cost reduction for linear roller screws will only be possible when Chinese manufacturers can transition from C5 to C3-grade mass production, while ensuring operational accuracy, long service life and reliability. Until then, claims of any Chinese advantage remain premature.

Originally developed in the mid-20th century for aerospace, defense, and industrial machinery, planetary roller screws have now found a broader commercial frontier in humanoid robotics.

Regardless of how the story unfolds, this is another tale of how emerging technologies can drive supply chain and engineering innovation.

Recommended Articles

Ni Tao worked with state-owned Chinese media for over a decade before he decided to quit and venture down the rabbit hole of mass communication and part-time teaching. Toward the end of his stint as a journalist, he developed a keen interest in China's booming tech ecosystem. Since then, he has been an avid follower of news from sectors like robotics, AI, autonomous driving, intelligent hardware, and eVTOL. When he's not writing, you can expect him to be on his beloved Yanagisawa saxophones, trying to play some jazz riffs, often in vain and occasionally against the protests of an angry neighbor.

- 1Sweden unveils Europe's first car park constructed using recycled turbine blades

- 2China's ultra-hot heat pump could turn sunlight into 2,372°F thermal power for industries

- 3Solar storm could cripple Elon Musk's Starlink satellites, causing orbital chaos

- 4Bermuda mystery solved: 12 mile-thick layer of buoyant, solid rock keeps it afloat

- 5Rolls-Royce tests powerful new engine for US Army’s next-gen MV-75 aircraft