US presidential elections are decided in the strange arena of the Electoral College. Candidates ultimately vie not for votes but for electoral votes, awarded by the states.

It means they compete fiercely in swing states where races are close. Kamala Harris and Donald Trump, for example, are currently battling for the prizes of Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

The Election Game is a simple model of these real-world contests and the strategies that shape them. We’ve dropped you in campaign headquarters and given you a healthy budget of resources. Can you spend it more efficiently than your rivals?

Real candidates also have a finite budget of time and money, and a menu of states in which to spend it. Their opponents face a similar problem. Underpinning their decisions — and yours, below — are the strategies dictated by “electoral maths” and the myriad paths to a majority. There are trillions of strategies to choose from, but don’t worry — you can run for president as many times as you like. Happy campaigning.

Loading

The real-world election game

The Electoral College is enshrined in the US Constitution, Section II, Clause 2: “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress.”

The scheme was a last-minute compromise between two competing plans in the 1780s: having the president elected by Congress (which could lead to “intrigues and cabals”) or elected by the people (who could succumb to “the little arts of popularity”).

There are now 538 electors in total — and Washington, DC, though not a state, also has electors thanks to the 23rd Amendment. The winner of each state wins its entire batch of electoral votes (except in Maine and Nebraska), which depends on the state’s size. And the winner of a majority of electoral votes wins the presidency.

Of course, there are crucial differences between the game and the election upcoming on November 5. In the real world, public opinion is shifting and hard to measure, campaigns unfold over time, many factors beyond expended effort determine a state’s winner — and you can’t simply click an “adjust strategy” button when it’s all over.

Under this system, it makes little sense for a Democratic candidate to campaign in a heavily Republican state, or vice versa — any marginal gains made among voters there are worthless when it comes to electors. So presidential elections are contested and decided in a handful of “swing states” or “battlegrounds” where the electorate is evenly split. Here marginal gains among voters can translate into a narrow majority of the state’s popular vote, a full pile of electors — and winning the White House. Candidates essentially ignore the rest of the country, save the odd fundraising trip to New York or California.

“You know what the tipping-point states are, so that’s where you spend your resources,” says Bob Shrum, who worked on the campaigns of Al Gore in 2000 and John Kerry in 2004. “That’s where you spend your money on television advertising, social media advertising. That’s where you spend candidate time.”

A narrow fulcrum of the Electoral College are considered swing states

Result by party and state (% points). Figures for 2024 are polling averages

Graphic: A dot plot depicting each presidential election since 1976. Each dot represents a state, and is placed left to right according to its partisan winning margin. The centre of the plot, which contains relatively few dots, is labelled “swing states”

Combinations of these tipping-point states give rise to specific winning strategies. For example, victories this year in three “blue wall” states — Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — would all but guarantee Harris the presidency.

Some states are staunchly partisan and ignored for decades. Other states drift — with demographic, economic or cultural tides — into or out of competitiveness. A few persist as steady bellwethers.

“You have a good understanding of where historical models have been, and past performance,” says Kevin Madden, a strategist on three Republican presidential campaigns, including Mitt Romney’s in 2012. “And then you have your most immediate data, which tells you about trends and informs the changes that are taking place in the electorate.”

Americans who live in swing states are subjected to a deluge of candidate visits and campaign advertising. Their votes are highly prized; the rest of us are just ticking boxes.

We can see the 2024 candidates’ strategic behaviour clearly in data. For example, Harris (and Joe Biden before her) and Trump have spent meaningfully on advertising in only seven states this year. In dozens of other states, they have spent approximately $0. This is the sort of targeted allocation you’ve undertaken above.

In the current race, presidential candidates have spent exclusively in the battleground states

Ad spending ($mn) vs polling margin (% points) by state in 2024

Graphic: A scatter plot of ad spending versus polling margin in the 2024 presidential campaign. The ad spending is dramatically higher in the states where the polling margin is small

Plenty of scorn has been heaped on the Electoral College in the past 237 years. Less than 20 per cent of the US population lives in a state considered electorally important this year. And twice this century, in 2000 and 2016, more Americans voted for the loser of the election than the winner, resulting in the presidencies of George W Bush and Donald Trump.

A group of (mostly Democratic-leaning) states has even joined a pact, vowing to bestow their electors on the national-vote winner and short-circuit the college; it would take effect if and when it ensured that the national-vote winner would win the presidency. But it’s difficult to convince swing states to sign on, and shun the attention lavished upon them.

So these are the arcane rules for now and the candidates play the game. It is unlikely, however, that the founding fathers considered the deep maths involved.

Electoral game theory

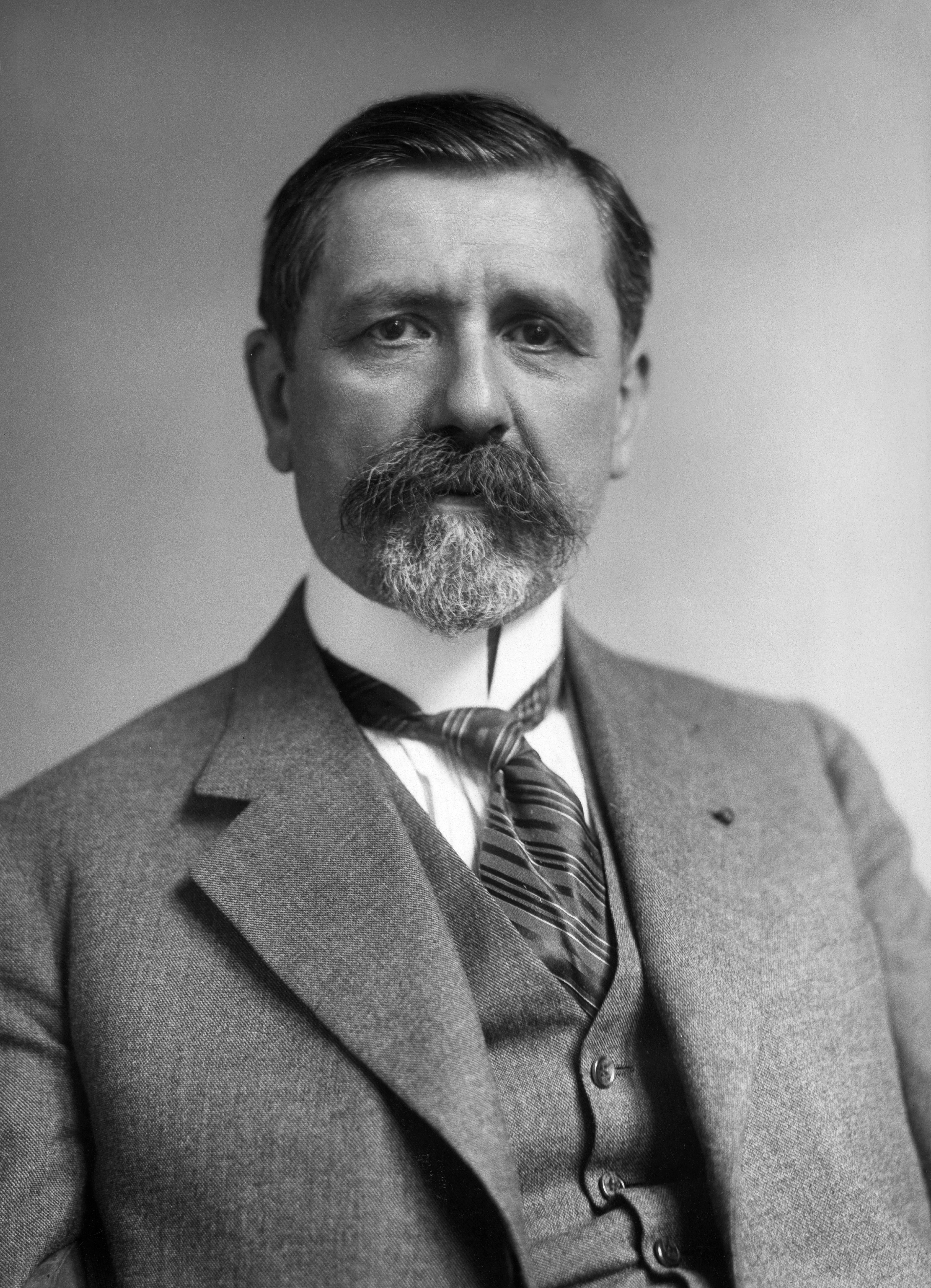

In a short paper in 1921, the French mathematician and politician Émile Borel introduced the rudiments of what would a century later become the game you have just played. In Borel’s version, “each player arranges the numbers he has chosen in a determined order” and wins “if the numbers chosen by him are superior to the corresponding numbers” chosen by his opponent. If a majority of a player’s numbers are higher, they win. This is the mathematical skeleton of a political campaign.

Borel recognised the wider applications of this simple structure, writing that “the art of war or of economic and financial speculation are not without analogy to the problems concerning games”.

“The art of play,” Borel continued, “depends on psychology and not on mathematics.” But there is plenty of mathematics, too. In the field of game theory, this sort of competition became a canonical object of study, known as the Colonel Blotto game. In 1950, a germinal paper from the military think-tank now called the Rand Corporation described a “continuous Colonel Blotto game” and the strategies of “the wily Blotto” facing his “enemy”.

The fictional colonel is in charge of an army of troops, as is his opponent, which he has to distribute across some number of battlefields. Whoever is victorious on more battlefields wins the war. Real-world situations, including research and development, patent races, strategic hiring, auctions and, of course, elections have been examined through Blotto games.

Solutions to these games — what game theorists call equilibria — are maddeningly difficult to find. They involve complex “mixed strategies”, randomising across intricate plans so that your opponent cannot outguess you. In this sense, presidential campaigns can be thought of as incredibly rich versions of rock, paper, scissors.

A 2006 paper by a trio of political scientists was among the first to “appreciate the problem posed by the Electoral College and its Colonel Blotto game-like structure” — they argue, for example, that Gore’s hairbreadth loss to Bush in 2000 was due to mistakes in his Blotto strategy. A 2014 paper by two economists spends 20 pages on Blotto maths before concluding that more work would yield “insights into more complicated variants of the game, which may be more representative of real military, political or other environments”.

For now, your campaigning may reveal some glimpses of strategic insight into the political environment. And the real game will be decided on November 5, when Americans — and especially Arizonans, Georgians, Michiganders, Nevadans, North Carolinians, Pennsylvanians and Wisconsinites — go to the polls.

This story is free to read so you can share it with family and friends who don’t yet have an FT subscription.

US Election Countdown

Our US Election Countdown newsletter delivers authoritative analysis on the race for the White House. Sign up to get the newsletter in your inbox every Tuesday and Thursday.

Additional work by Peter Andringa, Sam Joiner, Caroline Nevitt, Chris Campbell and Lizzy Bowler. Illustration by Pâté.

The game’s 10 battlegrounds were chosen for two reasons. First, they approximate those in the actual 2024 election, and have all appeared in the list of closest contests on the FT’s poll tracker. Second, they have tidy arithmetic, representing exactly 100 electoral votes and leaving a perfectly tied 219-219 tally in the “blue” and “red” states where the outcome is more certain.

Live submissions ended on November 7, 2025. You can download the full set of game submission data here.