Finding peace ‘when there is no peace’

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

SARAJEVO, BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA — The Christian Chronicle came here in search of peace.

Thirty years after a devastating siege, Sarajevo seemed peaceful enough on a sunny Friday at the height of the tourist season. Women from the Middle East, wearing black niqabs that covered everything but their eyes, strolled with their families along cobblestone streets, past restaurants that offer halal cheeseburgers and gelato. Young men from Western Europe stood in the footprints of Gavrilo Princip, the Bosnian Serb who assassinated Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914, sparking World War I.

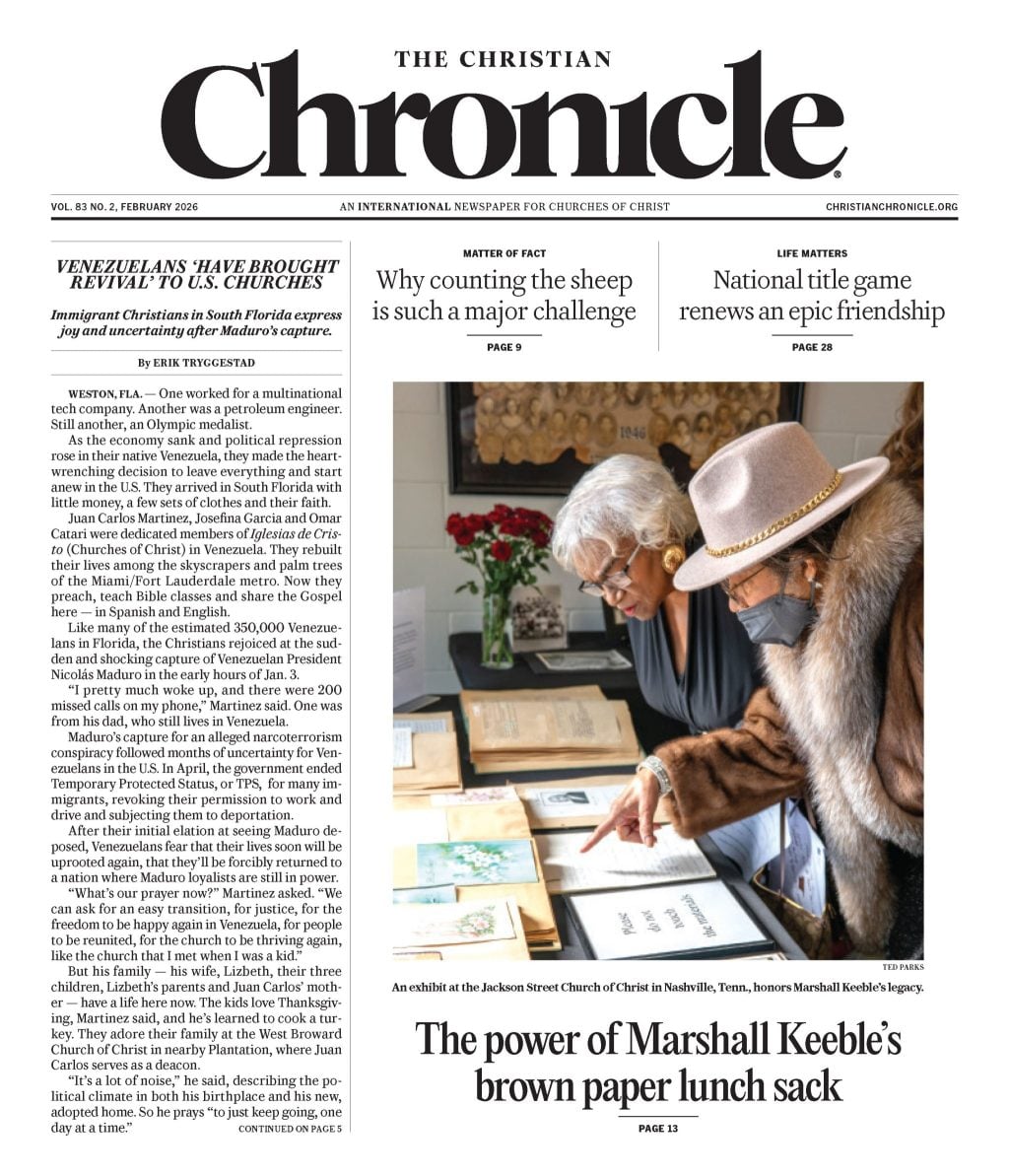

Tourists stroll through historic Sarajevo, a predominantly Muslim city.

The city’s name evokes images of destruction and suffering that ravaged this part of southeastern Europe, the Balkans, in the 1990s as the former Yugoslavia fractured. Three decades later, the Balkans rarely make headlines as deadly conflicts in Ukraine and Palestine drag on. Does the apparent peace here offer a model that Ukrainian, Russian, Arab and Jewish Christians can one day use to bring about reconciliation — after the guns finally fall silent?

The Chronicle visited the former communist nations of Bulgaria, Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Albania recently, searching for stories of shalom. The Hebrew greeting means more than just the absence of war. It’s a wholesome, lasting peace that restores broken relationships.

As the Old Testament prophet Jeremiah warned, some people — and nations — declare, “Peace, peace … when there is no peace.” Although the region is at peace, many of its people are far from shalom. Time and again in the Balkans, the Chronicle encountered resurgent waves of nationalism that aggravate old prejudices and grievances — the very kind that kindled World War I and, 75 years later, the Yugoslav Wars.

“It’s a sense. We call it ‘the smell of war,’” Christian minister Neno Arslanagić told the Chronicle.

And it’s back. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, a federation of quasi-autonomous republics created by the Dayton Agreement, electoral authorities recently removed Miloroad Dodik from his role as president of the Republic of Srpska. Dodik advocates leaving the country and uniting with Serbia. He also vows to keep leading Bosnia’s Serbs.

Arslanagić is part of a tiny minority of evangelical Christians in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Although the Balkans are the historic crossroads of three faiths — Catholicism, Orthodox Christianity and Islam — “it seems like the real message of the Gospel wasn’t present here at all,” Arslanagić said. “It was centuries of darkness.”

Street art in Sarajevo urges Bosnians to remember the July 11, 1995, genocide of Muslims by Bosnian Serbs in Srebrenica.

The Chronicle’s visit coincided with the 30th anniversary of the massacre in Srebrenica, 90 miles east of Sarajevo. An army of Bosnian Serbs and militia captured the town, where a lightly armed contingent of United Nations troops from Belgium was sheltering thousands of Bosnian Muslims. The U.N. soldiers handed over their protectees, and the Serbs executed more than 8,000 Muslim men and boys — the first legally recognized genocide in Europe since World War II.

“Christians slaughtered Muslims,” Arslanagić said, shaking his head in disbelief. “I don’t see Jesus teaching that.”

Graffiti in the Serbian capital, Belgrade, claims that only Serbs were victims of genocide.

Before Sarajevo, the Chronicle visited Draško Đenović, minister for the Karaburna Church of Christ in the capital of Serbia, Belgrade. Two bombed-out buildings still bear what the Serbian preacher called “NATO architecture,” reminders of the 1999 air campaign that killed 2,000 civilians. Spray-painted prominently on a building in downtown Belgrade, in English, were the words, “THE ONLY GENOCIDE IN THE BALKANS WAS AGAINST THE SERBS!”

But amid the words of defiance — declared across airwaves or scrawled in graffiti — there are signs of hope in the Balkans. Arslanagić produces Bible lessons and videos on social media to connect with new generations of Bosnians. He’s friends with Đenović, and they’ve worked together, united by their love for a common Savior. Though peace is fragile in this part of the world, the Chronicle found small examples of Christians practicing shalom.

• Croatia’s capital, Zagreb, virtually shut down during the Chronicle’s visit for a concert by Croatian singer Thompson, who takes his name from the machine gun he used during the war in the 1990s. His music has strong nationalist themes, and some of his fans display symbols associated with Croatia’s fascist Ustaše regime during World War II.

On the day of the concert, a small group of Christians gathered in an apartment — the first meeting place for Churches of Christ in Croatia, to celebrate a baptism. The next day, about an hour from Zagreb, Croatian and American Christians worshiped alongside the parents of children who attended two weeks of Christian camp in the city of Varazdin.

Graffiti and street art adorn an old bobsled track from the 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo, including a cartoon cat embracing a heart painted the colors of the Ukrainian flag.

• East of Zagreb, the Croatian city of Vukovar bears the scars of a violent siege by Serbian forces during the war. It’s also full of traumatized people. Croatian minister Vlado Psenko planted a Church of Christ in the war-battered city but died unexpectedly two years ago.

The church’s new minister, Goran Kumric, and his wife, Vanessa, are natives of Serbia. The small church is growing, and Christians who fought on opposite sides during the war worship side by side.

• In Belgrade, Đenović works with Serbian Orthodox and Catholic believers to promote biblical literacy and translate Christian authors into Serbian. Đenović once served in the Yugoslav army that battled Croatian soldiers during the war. Now he and a former Croatian soldier, Jurica Lazar, work together for Eastern European Mission, distributing Bibles in their native languages.

• In Albania, members of the Tirana Church of Christ sponsor outreach efforts — through Bible classes, Christian camps and a basketball league — to children in the country’s Roma communities. The Roma, often referred to as “gypsies,” are an underprivileged and persecuted minority across southeast Europe.

Back in Sarajevo, Arslanagić makes regular trips into the mountains that surround his city. He prays that the people of the Balkans will see faith as more than a part of their ethnic identity — and that his homeland will know real peace — shalom.

“I pray that God will lead me to be courageous and bold,” he said, “to use social media or whatever I’m doing to lead me into conversations.”

That’s a difficult task here, he said, but “the Lord can make miracles.”

ERIK TRYGGESTAD is President and CEO of The Christian Chronicle. Contact [email protected].