Update 6/10: Based on a short conversation with an engineering lead at X, some of the devices used at X are claimed to be using HSMs. See more further below.

Matthew Garrett has a nice post about Twitter (uh, X)’s new end-to-end encryption messaging protocol, which is now called XChat. The TL;DR of Matthew’s post is that from a cryptographic perspective, XChat isn’t great. The details are all contained within Matthew’s post, but here’s a quick TL;DR:

- There’s no forward secrecy. Unlike Signal protocol, which uses a double-ratchet to continuously update the user’s secret keys, the XChat cryptography just encrypts each message under a recipient’s long-term public key. The actual encryption mechanism is based on an encryption scheme from libsodium.

- User private keys are stored at X. XChat stores user private keys at its own servers. To obtain your private keys, you first log into X’s key-storage system using a password such as PIN. This is needed to support stateless clients like web browsers, and in fairness it’s not dissimilar to what Meta has done with its encryption for Facebook Messenger and Instagram. Of course, those services use Hardware Security Modules (HSMs.)

- X’s key storage is based on “Juicebox.” To implement their secret-storage system, XChat uses a protocol called Juicebox. Juicebox “shards” your key material across three servers, so that in principle the loss or compromise of one server won’t hurt you.

Matthew’s post correctly identifies that the major vulnerability in X’s system is this key storage approach. If decryption keys live in three non-HSM servers that are all under X’s control, then X could probably obtain anyone’s key and decrypt their messages. X could do this for their own internal purposes: for example because their famously chill owner got angry at some user. Or they could do it because a warrant or subpoena compels them to. If we judge XChat as an end-to-end encryption scheme, this seems like a pretty game-over type of vulnerability.

So in a sense, everything comes down to the security of Juicebox and the specific deployment choices that X made. Since Matthew wrote his post, I’ve learned a bit more about both of these things. In this post I’d like to go on a slightly deeper dive into the Juicebox portion of X’s system. This will hopefully shed some light on what X is up to, and why you shouldn’t use XChat.

What’s Juicebox even for?

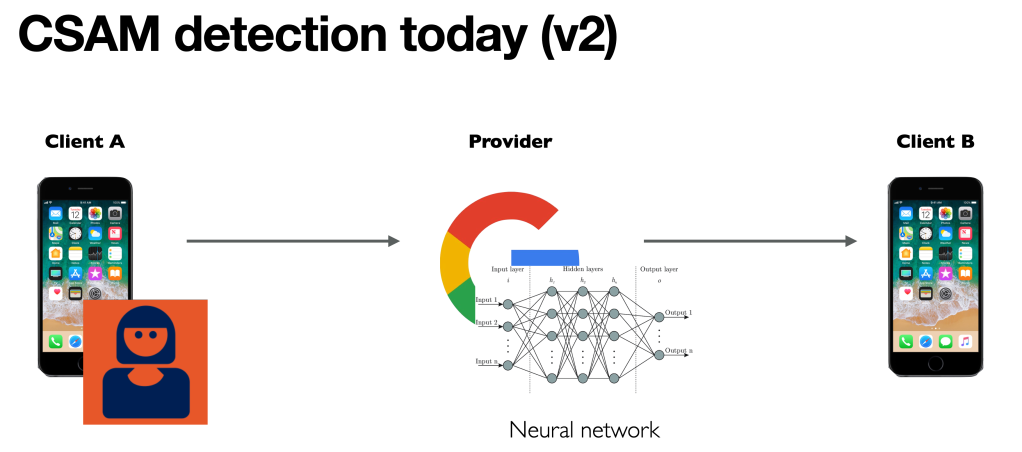

Many end-to-end encryption (E2E) apps have run into a specific problem: these systems require users to store their own secret keys. Unfortunately, users are just plain bad at this.

Sometimes we forget keys because we lose our devices. Often we have more than one device, which means our keys end up in the wrong place. A much worse situation occurs when apps want to work in ordinary web browsers: this means that secret keys have to be airlifted into that context as well.

The obvious remedy for this problem is just to store secret keys with the service provider itself. This is convenient, but completely misses the whole point of end-to-end encryption, which is that service providers should not have access to your secrets! Storing decryption keys — in an accessible form — on the provider’s servers is absolutely a no-go.

One way out of this conundrum is for the user to encrypt their secret key, then upload the encrypted value to the service provider. In theory, they can download their secret keys anytime they want and they should know that their secrets are safe. But of course there’s a problem: what secret key are you going to use to encrypt your secret key!? Answering this question quickly leads you into an infinite pile of turtles.

Rather than descend into paradox, systems like Juicebox, Signal SVR, and iCloud Key Vault offer an alternative. Their observation is that while cryptographic keys are hard to hang on to, users generally do remember simple passwords like PINs, particularly if they’re asked to re-enter them periodically. What if we use the user’s PIN/password to encrypt the stronger cryptographic key that we upload to the server?

While this is better than nothing, it isn’t good. Most human-selected passwords and PINs make for terrible cryptographic keys. In particular, short PINs (like the 6-digit decimal pins many people use for their phone passcode) are vulnerable to efficient brute-force guessing attacks. A six-digit PIN provides at most 220 security, which is what cryptographers call “a pretty small number.” Even if you use a “hard” key derivation function like scrypt or Argon2 with insane difficulty settings, you’re still probably still going to lose your data.

Fortunately there is another way.

For many years, cryptographers have considered the problem of turning “weak secrets” into strong ones. The problem is sometimes known as password hardening, and doing it well usually requires additional components. First, you need to have some strong cryptographic secret that can be “mixed” into the user’s password to make a produce a truly strong encryption key. Second, you need some mechanism to limit the number of guessing attempts that the user makes, so an attacker can’t simply run an online attack to work through the PIN-space. This cannot be enforced using cryptography alone: you must add a server (or servers) to enforce these checks. Critically, the server will place limits on how many incorrect passwords the user can enter: e.g., after ten incorrect attempts, the user’s account gets locked or erased.

In one sense, we’re right back where we started: someone needs to operate a a server. If that server is under the control of the service provider, then they can disable the guessing limits and/or extract the server’s secret key material, at which point you’re back to square one.

Many services have engineered some reasonable solutions to this problem, however. They boil down to the following alternatives, which can be implemented separately or together:

- The server can be implemented inside of a specialized Hardware Security Module, which is set up so that the provider cannot reprogram it or access its key material (at least, after it’s been configured.) This approach was pioneered by Apple, and is now in use by iCloud Key Vault, Signal SVR, WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger.

- Alternatively, the server can be “split up” into multiple pieces that are each run by different parties. The idea here is that the user must contact T out of N different servers in order to obtain the correct key (a common example is 2-of-3.) As long as an attacker cannot compromise T different servers, the combined system will still be able to enforce the guessing limits and prevent attackers from getting the key. Naturally this idea fundamentally depends on the assumption that the servers are not run by the same party!

And at last, we come to Juicebox.

Juicebox is an software-based distributed key hardening service that can be implemented across multiple servers. Users can “enroll” their account into the system, at which point the Juicebox servers will convert their PIN/password into a strong cryptographic key (by mixing it with a secret stored on the Juicebox servers.) Later on, they can contact the Juicebox servers and — assuming they enter the right password, and don’t try too many incorrect guesses — they can obtain that same cryptographic key from the system. Users can specify the number of servers (N) and the threshold (T), and the goal is that the system can survive the loss (or unavailability) of N-T servers, and it should retain its security even if an attacker compromises A<T of them. Most critically, Juicebox enforces limits: if too many incorrect passwords are entered, Juicebox will lock or destroy the user’s account.

In principle, Juicebox servers (called “realms” in the project’s lingo) can be either “software based” or they can be deployed inside of HSMs. However, to the best of my knowledge the HSM capability is not fully supported outside of Juicebox’s one test deployment, and has not been used in deployments (at X or anywhere else.) Update 6/10: but see further below! This means the security of XChat’s version of Juicebox probably comes down to a question of who runs the servers.

So who runs X’s Juicebox servers, and do they use HSMs?

To the best of my knowledge, all of the XChat servers are run in software by Twitter/X itself. If this turns out to be incorrect, I will be thrilled to update this post.

Update: this tweet by an engineering lead claims that they are actually HSMs, and Twitter has just not publicized this or published the key ceremonies that were used to set them up. I am very confused by this because it seems extremely backwards! The problem with this late claim is that there’s really no way to verify this fact other than one or two tweets from someone at X.

To put this more explicitly, without any protections like the verifiable use of HSMs and/or distributing Juicebox servers across mutually-distrustful operators, having three servers does relatively little to protect users’ secrets against the service operator. And even if X is secretly implementing these protections, implementing them in secret is stupid. As a wise man once said:

Verifying that the XChat Juicebox servers are software-only is more complicated. Digging around in the Juicebox Github, you’ll find a software-only as well as an HSM-specific implementation of their “realms.” Specifically, there is an entire repository dedicated to supporting Juicebox on Entrust nShield Solo XC HSMs (see here for instructions) although this same code can also be deployed outside of HSMs. There is even a cool “ceremony” document that a group of administrators can perform to certify that they set the HSM up correctly, and that they destroyed all of the cards that could allow it to be re-programmed!

However, after speaking to Juicebox’s protocol designer Nora Trapp, I’m doubtful that any of this is in use at X. Nora told me that the Juicebox project shut down over a year ago and the engineers moved on, and what code there is now open source and not actively maintained (this matches with project commits I can see.) Nora also looked at XChat’s Juicebox deployment and sent me the following commentary:

From what I’ve seen, there are four realms currently in use by Twitter:

realm-a.x.com,realm-b.x.com,realm-east1.x.com, andrealm-west1.x.com.

realm-aandrealm-bare definitely software realms. They don’t use Noise (only true of software realms) and rely solely on TLS. In contrast, HSM-backed realms use Noise within TLS, with TLS terminated at the LB and Noise inside the HSM.realm-east1andrealm-west1appear to run code from juicebox-hsm-realm. For example, hittinghttps://realm-east1.x.com/livezshows they’re likely using the repo unmodified frommain. However, this doesn’t mean they’re HSM-backed. The repo includes a “software HSM” for testing, which is insecure and doesn’t provide actual HSM properties.Timing analysis (e.g. via the convenient

x-exec-timeresponse header X left in place) suggests these are indeed using the software HSM. Real HSMs are typically significantly slower. And even if by some chance they’re running real HSMs, no ceremony has been published, so there’s no reason to trust they’re secure or that the key material isn’t exfiltrated.

Nora also wrote a post very recently warning deployers to stop placing all servers under the control of a single service provider, which seems very applicable to what Twitter/X is doing.

Obviously this doesn’t prove that X isn’t using HSMs. Though, obviously, there’s no reason that you should hope something is secure when the deployer is going out of their way not to tell you it is. When it comes to XChat, my advice is that you should assume this deployment is (1) entirely in software, and (2) all Juicebox “realms” are run by the same organization. This means you should assume that your decryption keys could be recovered by X’s server administrators with at most a little fuss, unless you use a very strong password.

That’s bad, but let’s talk more about the Juicebox protocol anyway!

If all you came for was a bit of discussion about the security posture of XChat, then Matthew’s post and the additional notes above are all you need. Unless and until X proves that they’re using HSMs (and have destroyed all programming cards) you should just assume that their Juicebox instantiation is based on software realms under X’s control, and that means it is likely vulnerable to brute-force password-guessing attacks.

The rest of this post is going to look past X.

Let’s assume that a deployer has configured Juicebox intelligently: meaning that some/all realms will be deployed inside of HSMs, and/or realms are spread across multiple organizational trust boundaries — such that no single organization can easily demand recovery of anyone’s password. The question we want to ask now is: what guarantees does Juicebox provide in this setting, and how does the protocol work?

Threshold OPRFs. The core cryptographic primitive inside of Juicebox is called a threshold oblivious pseudorandom function, or t-OPRF. I’ve written about OPRFs before, specifically in the context of Password-Authenticated Key Agreement (PAKE schemes.) Nonetheless, I think it’s helpful to start from the top.

Let’s leave aside the “oblivious” part for a minute. PRFs are functions that take in a key K and a string P (for example, a password), and output a string of bits. We might write as:

O = PRF(K, P)

Provided that an attacker does not know the key, the resulting string O should look random, meaning that the output of a PRF makes for excellent cryptographic keys. In many practical implementations, PRFs are realized using functions like HMAC or CBC-MAC; however, there are many different ways to build them.

An oblivious PRF (OPRF) is a two-party cryptographic protocol that helps a client and server jointly compute the output of a PRF. It works like this:

- Imagine a server has the cryptographic key K.

- The client has their string P (such as a password.)

- At the end of a successful protocol run, the client should obtain O = PRF(K, P). The server gets no output at all.

- Critically: neither party should learn the other party’s input, and the server should not learn the client’s result, either.

With this tool in hand, it’s easy to build a very simple password-hardening protocol. Simply configure the server with a key K (preferably a different key for every user account), and then have the client run the OPRF protocol with the server to obtain O = PRF(K, P). The resulting value O will make for an excellent encryption key, which the client can use to encrypt any secret values it wants. The best part of this arrangement is that the OPRF protocol ensures that the server never learns the user’s password P, so no information leaks even if the server is fully malicious!

This basic design has some limitations, of course. It does not allow the server to limit the number password guesses, nor does it allow us to spread the process over many different servers.

Addressing the first problem is easy. When the client first registers their account with the server, they can run the OPRF protocol to obtain O = PRF(K, P). Next, they compute some “authenticator tag” T that’s derived in some way from the secret O. They can then store that tag T on the server. When a user returns to log back into the system, the client and server can run the OPRF protocol, and then conduct some process to verify that the O received by the client is consistent with the tag T stored at the server. (The exact process for doing this is important, and I’ll discuss it further below.) If this is unsuccessful, then the server can increment a counter to indicate an incorrect password guess on that user’s account. If the protocol completes successfully, then the server should reset that counter back to zero.1

Critically, when the counter reaches some maximum (usually ten incorrect attempts), the server must lock the user’s account — or much better, delete the account-specific key K. This is what prevents attackers from systematically guessing their way through every possible PIN.

Splitting up the PRF into multiple servers is only slightly more complicated. The basic idea relies on the fact that the specific OPRF used by Juicebox is based on elliptic curves, and this makes it very amenable to threshold implementations. I’m going to put the details into a separate page right here since it’s a little boring. But you should just take away that (1) the service operator can split up the key K across multiple servers, and (2) a client can talk to any T of them and eventually obtain PRF(K, P).

How does the client prove it got the right key, and what attacks are there?

You’ll notice that these “incorrect attempt” counters are a big part of the protection inside of a system like Juicebox. As long as an attacker can only make, say, a maximum of ten incorrect guessing attempts, then even a relatively weak password like 234984 is probably not too bad. If an attacker can make many possible guesses, then the whole system is fairly weak.

Note that in most of these attacks we are going to make the very strong assumption that the server operator is the attacker and that they’ve deployed Juicebox in such a way that they can’t just read the secrets out of their own instance (e.g., in this hypothetical scenario, they have deployed Juicebox using HSMs or distributed trust.) Since the whole point of end-to-end encryption is that users’ secret keys should not be known to a server operator, this isn’t too strong of an assumption. Moreover, we’ve recently seen governments make secret requests to companies like Apple to force them to bypass their end-to-end encrypted services. This means that both hacking and legal compulsion are real concerns.

Within this setting there exist a handful of attacks that could come up in a system like Juicebox. Some are easier than others to prevent:

- An attacker could try to enter a few password guesses, then wait for the real user to log in. As long as the real user enters the correct password, the attempt counter on the server(s) will drop back to zero. This attack could allow you to make up to, say, nine invalid guesses for each genuine user login.2

The existence of this attack is kind of unavoidable in systems like Juicebox. Fortunately it’s probably not a very efficient attack. Unless the user is logging on constantly (say, because a web browser caches the user’s password and runs the protocol automatically), the rate of attacker guesses is going to be very low. Moreover: this attack can be mitigated by having the server inform the client of the number of incorrect guesses it’s seen since the last time the user logged in, which should help the user to detect the fact that they’re under attack. - If the servers don’t coordinate with each other, a smart attacker could try to guess passwords against different subsets of the Juicebox servers: for example if 2-of-10 servers are needed to recover the key, then an attacker actually could actually obtain many more than ten guesses. This is because the attacker could make at least ten attempts with each subset comprising two servers, before all the necessary servers locked them out. Juicebox’s HSM implementation actually goes to some lengths to prevent this (as SVR did before them) by having servers share the current password counter values with each other using a consensus protocol.

Another possibility is that a malicious (software) server operator could try to attack the protocol directly. Just for fun, I thought it might be interesting to conclude with one possible attack I noticed while perusing the protocol description. I’m almost certain this won’t work in practice — and the Juicebox developers agree, but I thought it was a fun illustration of the types of vulnerabilities that show up in these systems.

Recall that whenever a Juicebox client successfully completes the protocol with a set of T servers, it must somehow convince those servers that it obtained the right key. This is necessary because a correct password entry should reset those servers’ attempt counters back to zero, whereas an incorrect guess will increase the attempt counter. (Without a mechanism to reset the counter, the counter will keep rising until the user’s account gets permanently locked.)

The client deals with this by first computing a value called the unlockKey from the t-OPRF output, and then calculating a set of “tags” called the unlockKeyTags, one for each server (realm) in the system:

The calculation of each unlockKeyTags[i] value is customized to include the “realm ID” of the server, which means that the tag for server i is specific only to that server. It cannot be extracted from a malicious server i and replayed against server j, which would be very bad. The client then sends each value unlockKeyTags[i] to the appropriate server. The servers can verify the received tag against a copy they stored during the account registration process. If it matches, they reset their counter back to zero as follows:

However, the only thing that differentiates these tags from one another is the notion that realm IDs for different servers will always be different. What if this assumption isn’t correct?

The attack I’m concerned about is pretty bizarre, but it looks like this. Imagine a user has previously registered its key into several real HSM-based servers. Now someone hacks into the service provider. This hacker “tricks” clients into sending subsequent login requests to a new set of malicious servers that the attacker spins up using software (i.e., no HSM protections.)

Ordinarily this attack wouldn’t be a disaster, since the OPRF should prevent those new servers from learning the user’s password inputs. But let’s imagine that the hacker sets the “realm ID” of these new servers to be identical to the realm ID of the real (HSM) servers. In this case, the value of unlockKeyTag[i] sent to the malicious servers will be identical to the value that would have been stored within the HSM-based servers. Once the attacker learns this value, they can make an unlimited number of guesses against the HSM server with the same realm ID: this is because the stolen unlockKeyTags[i] value will reset the HSM server’s counter.

I ran this past Nora and she pointed out a number of practical issues that will probably make this sort of attack much less likely to work, but it’s still fun to find this sort of thing. More importantly, I think it shows how delicate distributed protocols like this can be, and how sometimes one’s assumptions may not always be valid.

Post image: Noah Berger/AP Photo

Notes:

- Obviously this can be dangerous. An attacker who just wants to deny service to the user can enter deliberately-incorrect guesses until the user’s account becomes permanently locked. To prevent this, most services require that you log In using a traditional password first, then you can access the password strengthening server second. Some systems also add time delays, to ensure that an attacker cannot quickly exhaust the counter.

- The “try N attempts and then let the client log in normally” attack was outlined to me by Ian Miers.

tangle with U.S. over data access

tangle with U.S. over data access