I am surprised how often I hear an organization operate under the belief that they can really, truly can control what a remote client does under any situation. Here is today's lesson on how you can never know what computer is on the other end of the Cisco VPN tunnel or how it is behaving, thanks to more "

opt-in security".

Step 1: Break the misconception that Cisco VPN concentrators authenticate which computer is on the other end of the tunnel.

Cisco VPNs authenticate

people, not

computers. When the connection is initiated from a client, sure the client passes a "group password" before the user specifies her credentials, but there's nothing that really restricts that group password to your organization's computers.

Consider this: any user who runs the Cisco VPN Client has to have at least read access to the VPN profile (the .pcf files stored in the Program Files --> Cisco Systems --> VPN --> Profiles folders on Windows systems). If the user has READ access, any malware unintentionally launched as that user could easily steal the contents of the file ... and the "encrypted" copy of the group password stored within it. Or, a

Cisco VPN client can be downloaded from the web and the .pcf VPN profile can be imported into it. At that point, it's no longer certain that the connection is coming from one of your computers.

Step 2: Break the misconception that the client is even running the platform you expect.

So since any user has READ access to the .pcf VPN profiles, they can open up the text config file in a text editor like notepad, peruse the name-value pairs for the "enc_GroupPwd" value, copy everything after the equal sign ("="), and paste it into a

Cisco VPN client password decoder script like this one. A novice, in less than a minute, can have everything she needs to not only make VPN connections from an unexpected device, but also from an unexpected platform. Not to mention the group password is not really all that secret.

Cisco VPN encrypted group passwords, like any encrypted data that an automated system (i.e. software) needs to unlock without interrogating user for a key value that only a human knows, must be stored in such a way that is readable for the software. Even though the name/value pair for group passwords in Cisco profiles is labeled as "encrypted" group password, the software needs to be able to decrypt it to use it when establishing VPN tunnels, which means the group password is also read-accessible for any reverse engineer (

hence this source code in C). So it is now trivial to decode a Cisco group password. This is not an attack on crypto, this is an attack on key management coupled with a misunderstanding on how compiled programs work.

Now that a "decrypted" copy of the group password is known, the

open source "vpnc" package can pretend to be the same as the commercial Cisco version. Here's how simple Ubuntu makes configuring vpnc to emulate a Cisco client:

A Cisco VPN concentrator (or any other server in a client-server relationship) cannot know for sure what the remote client's platform really is. Any changes Cisco makes to its client to differentiate a "Cisco" client by behavior from, say, a "vpnc" client, can be circumvented by doing a little reverse engineering and coding the emulation of the new behavior into the "vpnc" package. An important thing to keep present in one's mind is that compiled applications, although obscure, are not completely obfuscated beyond recognition. A binary of a program is not like a "ciphertext" in the crypto world. It has to be "plaintext" to the OS & CPU that execute it. If it was not readable, then the instructions could not be read and loaded into the CPU for execution. So, any controls based on compiled code are fruitless. Sure, there will be a window of time from when the changes are deployed in the official client to when they are emulated by a hacked client, but reverse engineering and debugging tools (such as

bindiff and

OllyDbg) are getting more and more sophisticated, reducing the time barrier.

Step 3: Break the misconception that you can remotely control a client's behavior.

A "client" is just that ... it's a "client". It's remote. You cannot physically touch it. Any commands you send to it have to be accepted by it before they are executed. Case in point with the Cisco VPN client is the notion that

"network security" people try to perpetuate: "split-tunneling is bad, so let's disable it." Network security people don't like split tunnels or split routes because they view it as a way of bridging a remote client's local network and the organization's internal network. However, it's futile to get all worked up about it. If you trust clients to remote in, then you cannot control how they choose to route packets (though you can pretend that what I show below doesn't really exist, I guess.)

In the same Ubuntu screen shot above, there's a quick and easy way to implement split-tunnels. It's the "Only use VPN connection for these addresses" check box. Check the box and specify the IP ranges. Voila! You've got a split tunnel. Don't want to route the Internet through your company's slow network or cumbersome filters? Check the box. Want to access a local file share while connected to an app your organization refuses to web-enable? Check the box. You get the idea. This is an excellent example of how many "network security" people believe they can control a remote client, yet as you can see, the only way to continue the misconception is to

ignore distributed computing principles.

Doing what I described above is certainly not "new" information-- clearly because there are now GUIs to do it (so it's obviously very mature). However, the principles are still not well known and we have vendors like Cisco continuing the notion that you can remotely control a client by upping the ante. Many organizations' network security people are considering the deployment of NAC ("network access control") with VPN. Microsoft has had an implementation of it (they call it NAP for "network access protection") for years. The problem is, it's based on this false sense of "

opt-in security" just like split tunnels. Let's look at an analogy ...

Physical Security Guard: "Do you have any weapons?"

Visitor: [shoves 9mm handgun further into pants] "No, of course not."

Guard: "Are you on drugs?"

Visitor: [double-checks the dime bag hasn't fallen out of his jacket pocket] "No, I never touch the stuff."

Guard: "Do you have any ill intent?"

Visitor: [pats the "Goodbye cruel world" letter in his front pocket] "Absolutely not!"

How is that any different from this?

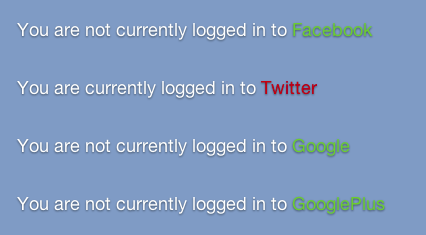

Server: "Are you running a platform I expect?"

Client: "Of course" (it says from the unexpected platform)

Server: "Are you patched?"

Client: "Of course" (why does that even matter if I'm on a different platform from the patches?)Server: "Are you running AV?"

Client: "Of course" (your AV doesn't even run on my platform)

The answer: it's not any different. Both are fundamentally flawed ideas.

So, to refute implementation specific objections, there are two key ways for a project, such as the vpnc project, to choose to not "

opt-in" if so desired. They both involve lying to the server (VPN concentrator):

- Take the "inspection" program the server provides the client to prove the client is "safe" and execute the inspection program in a spoofed or virtual environment. When the inspection program looks for evidence of Microsoft Windows + latest patches + AV, spoof the evidence they exist.

- Reverse engineer the "everything is OK, let 'em on the network" message the inspection program sends the server, then don't even bother executing the inspection program, just cut to the chase and send the all-clear message by itself.

Sure, there may be some nuances that will make this slightly more difficult, such as adding some dynamic or more involved deterministic logic into the "inspection" program, but the more sophisticated the checks are, the more likely the whole process will break and generate false positives for legit users who are following the rules. The more false positives, the less likely customers will deploy the flawed technology.

...

So to recap: you cannot control a client or truly know anything about it. It's just not possible, so security practitioners should look to setting policies that include the fact that you cannot control a remote client. For a great in-depth review of all of these principles (with tons more examples), I suggest picking up a copy of

Gary McGraw's and Greg Hoglund's "Exploiting Software: How to break code" book.