Evidence E is misleading with regard to a hypothesis H provided that Bayesian update on E changes one’s credence in H in the direction opposed to truth. It is known that pretty much any evidence is misleading with regard to some hypothesis or other. That’s no tragedy. But sometimes evidence is misleading with regard to an important hypothesis. That’s no tragedy of the shift in the credence of that important hypothesis is small. But it could be tragic if the shift is significant—think of a quack cure for cancer beating out the best medication in a study due to experimental error or simply chance.

In other words, misleadingness by itself is not a big deal. But significant misleadingness with respect to an important hypothesis can be tragic.

Suppose I am lucky enough to start with consistent credences in a limited algebra F of propositions including q, and suppose I have a low credence in a consistent proposition q. Now two friends, whom I know for sure to speak only truth, speak to me:

Alice: “Proposition q is actually true.”

Bob: “She’s right, as always, but the fact that q is true is significantly misleading with respect to a number of quite important hypotheses in F.”

What should I do? If I were a perfect Bayesian agent, my likelihoods would be sufficiently well defined that I would just update on Alice saying her piece and Bob saying her piece, and be done with it. My likelihoods would embody prior probability assignments to hypotheses about the kinds of reasons that Alice and Bob could have for giving me their information, the kinds of important hypotheses in F that q could be misleading about, etc.

But this is too complicated for a more ordinary Bayesian agent like me. Suppose I could, just barely, do a Bayesian update on q, and gain a new consistent credence assignment on F. Even if Bob were not to have said anything, updating on q would not be ideal, because the ideal agent would update not just on q, but on the facts that Alice chose to inform me of q at that very moment, in those very words, in that very tone of voice, etc. But that’s too complicated for me. For one, I don’t have enough clear credences in hypotheses about different informational choices Alice could have made. So if all I heard was Alice’s announcement, updating on q would be a reasonable choice given my limitations.

But with Bob speaking, the consequences of my simply updating on q could be tragic, because Bob has told me that q is significantly misleading in regard to important stuff. What should I do? One possibility is to ignore both statements, and leave my credences unchanging, pretending I didn’t hear Alice. But that’s silly: I did hear her.

But if I accept q on the basis of Alice’s statement (and Bob’s confirmation), what should I do about Bob’s warning? Here is one option: I could raise my credence in q to 1, but leave everything else unchanged. This is a better move than just ignoring what I heard. For it gets me closer to the truth with regard to q (remember that Alice only says the truth), and I don’t get any further from the truth regarding anything else. The result will be an inconsistent probability assignment. But I can actually do a little better. Assuming q is true, it cannot be misleading about propositions entailed by q. For if q is true, then all propositions entailed by q are true, and raising my credences in them to 1 only improves my credences. Thus, I can safely raise my credence in everything entailed by q to 1. Similarly, I can safely lower my credence in anything that entails ∼q to 0.

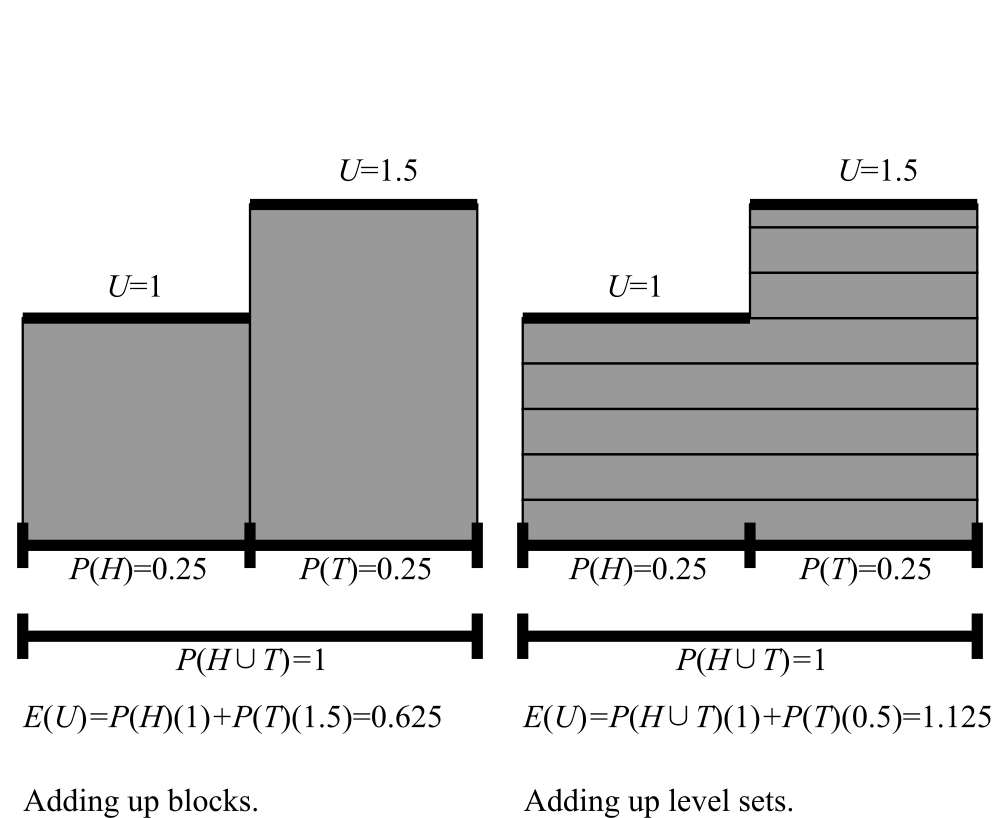

Here, then, is a compromise: I set my credence in everything in F entailed by q to 1, and in everything in F that entails ∼q to 0, and leave all other credences for things in F unchanged. This has gotten me closer to the truth by any reasonable measure. Moreover, the resulting credences for F satisfy the Zero, Non-negativity, Normalization, Monotonicity, and Binary Non-Disappearance axioms, and as a result I can use a Level-Set Integral prevision to avoid various Dutch Book and domination problems. [Let’s check Monotonicity. Suppose r entails s. We need to show that C(r)≤C(s). Given that my original credences were consistent and hence had Monotonicity, the only way I could lack Monotonicity now would be if q entailed r and s entailed ∼q. Since r entails s, this would mean that q would entail ∼q, which would imply that q is not consistent. But I assumed it was consistent.]

I think this line of reasoning shows that there are indeed times when it can be reasonable to have an inconsistent credence assignment.

By the way, if I continue to trust the propositions I had previously assigned extreme credences to despite Bob’s ominous words, an even better update strategy would be to set my credence to 1 for everything entailed by q conjoined with something that already had credence 1, and to 0 for everything that when conjoined with something that had credence 1 entails ∼q.