Sunday, January 28, 2024

Measure screen latency

Saturday, July 10, 2021

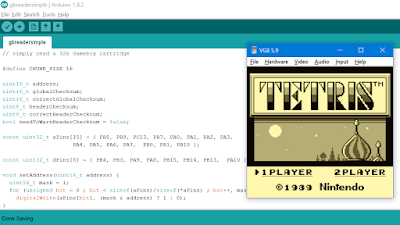

Reading a Game Boy Tetris cartridge

I saw a small rectangular PCB on the sidewalk not far from my house. It looked interesting. I left it for a couple of days in case someone lost it and returned for it. A web search showed it was the PCB from a Game Boy cartridge. Eventually, I took the PCB home, and made it a challenge to extract the data from it with only the tools I had at home and without harming the PCB (so, no soldering).

This PCB was from a ROM-only cartridge, 32K in size (I was able to identify it from the part number and photos online as likely to be Tetris), so it should have been particularly easy to read. The protocol is described here.

While the Game Boy cartridges run at 5V, the only microcontroller I had available with enough GPIOs and ready to use was an stm32f103c "black pill" which runs at 3.3V. Fortunately, it has a number of 5V-tolerant GPIOs, so there was some hope that I could run the cartridge at 5V and read it with the microcontroller.

The Game Boy I didn't have a cartridge connector, but fortunately the PCB had plated through-holes on all but two of the lines, and they fit my breadboard jumper wires very nicely. I used test clips for the remaining two lines (VCC and A0). After some detours due to connection mistakes and a possibly faulty breadboard or GPIO, I ended up with this simple setup (what a mess on the breadboard!).

1. Connect D0-D7 on the cartridge to 5V-tolerant inputs, connect A0-A14 on the cartridge to outputs, ground GND, A15 and RD (CS and RS were not connected to anything on the cartridge), and connect VCC to a power supply (it turned out that all my worries about 3.3V/5V were unnecessary: supplying 3.3V, 4.5V or 5V all worked equally well).

2. Write a 15-bit address to A0-A14. Wait a microsecond (this could be shaved down, but why bother?). Read the byte from D0-D7. Increment address. Repeat. Check the header and ROM checksums when done. Arduino code is here. (I just copied and pasted the output of that into a text file which I then processed with a simple Python script.)

It works! I now have a working Tetris in an emulator, dumped from a random PCB that had been lying on the sidewalk through torrential rains!

I've played many versions of Tetris. This one plays very nicely.

Some technical notes:

- I got advice from someone to set pulldown on the D0-D7 lines. Turns out that makes no difference.

- Cartridges that are more than 32K would need some bank switching code.

Thursday, October 15, 2020

Synchronization and the unity of consciousness

The problem of the unity of consciousness for materialists is what makes activity in different areas of the physical mind come together into a single phenomenally unified state rather than multiple disconnected phenomenal states. If my auditory center active in the perception of a middle C and my visual center is active in the perception of red, what makes it be the case that there is a single entity that both hears a middle C and sees red?

We can imagine a solution to this problem in a computer. Let’s say that one part of the computer has and representation of red in one part (of the right sort for consciousness) and a representation of middle C in another part. We could unify the two by means of a periodic synchronizing clock signal sent to all the parts of the computer. And we could then say that what it is for the computer to perceive red and middle C at the same time is for an electrical signal originating in the same tick of the clock to reach a part that is representing red (in the way needed for consciousness) and to reach a part that is representing middle C.

On this view, there is no separate consciousness of red (say), because the conscious state is constituted not just by the representation of red (say) in the computer’s “visual system”, but by everything that is reached by the signals emanating from the clock tick. And that includes the representation of middle C in the “auditory system”.

The unification of consciousness, then, would be the product of the synchronization system, which of course could be more complex than just a clock signal.

This line of thought shows that in principle the problem of the unity of consciousness is soluble for materialists if the problem of consciousness is (which I doubt). This will, of course, only be a Pyrrhic victory if it turns out that no similar pervasive synchronization system is found in the brain. The neuroscience literature talks of synchronization in the brain. Whether that synchronization is sufficient for solving the unity problem may be an empirical question.

The above line of thought also strongly suggests that if materialism is true, then our internal phenomenal timeline is not the same as objective physical time, but rather is constructed out of the synchronization processes. It need not be the case for this that the representation of red and the representation of middle C happen at the same physical time. A part further from the clock will receive the synchronizing signal later than a part closer to the clock, and so the synchronization process may make two events that are not simultaneous in physical time be simultaneous in computer time. I suspect that a similar divide between mental time and physical time is true even if dualism is (as I think) true, but for other reasons.

Thursday, May 7, 2020

Swapping ones and zeroes

Decimal addition can be done by a computer using infinitely many algorithms. Here are two:

Convert decimal to binary. Add the binary. Convert binary to decimal.

Convert decimal to inverted binary. Inv-add the binary. Convert inverted binary to decimal.

By conversion between decimal and inverted binary, I mean this conversion (in the 8-bit case):

- 0↔11111111, 1↔11111110, 2↔11111101, …, 255↔00000000.

By inv-add, I mean an odd operation that is equivalent to bitwise inverting, adding, and bitwise inverting again.

You probably thought (or would have thought had you thought about it) that your computer does decimal addition using algorithm (1).

Now, here’s the fun. We can reinterpret all the physical functioning of a digital computer in a way that reverses the 0s and 1s. Let’s say that normally 0.63V or less counts as zero and 1.17V or higher counts as one. But “zero” or “one” are our interpretation of analog physical states that in themselves do not have such meanings. So, we could deem 0.63V or less to be one and 1.17V or higher to be zero. With such a reinterpretation, logic gates change their semantics: OR and AND swap, NAND and NOR swap, while NOT remains NOT. Arithmetical operations change more weirdly: for instance, the circuit that we thought of as implementing an add should now be thought of as implementing what I earlier called an inv-add. (I am inspired here by Gerry Massey’s variant on Putnam reinterpretation arguments.)

And if before the reinterpretation your computer counted as doing decimal addition using algorithm (1), after the reinterpretation your computer uses algorithm (2).

So which algorithm is being used by a computer depends on the interpretation of the computer’s functioning. This is a kind of flip side to multiple realizability: multiple realizability talks of how the same algorithm can be implemented in physically very different ways; here, the same physical system implements many algorithms.

There is nothing really new here, though I think much of the time in the past when people have discussed the interpretation problem for a computer’s functioning, they talked of how the inputs and outputs can be variously interpreted. But the above example shows that we can keep fixed our interpretation of the inputs and outputs, and still have a lot of flexibility as to what algorithm is running “below the hood”.

Note that normally in practice we resolve the question of which algorithm is running by adverting to the programmers’ intentions. But we can imagine a case where an eccentric engineer builds a simple calculator without ever settling in her own mind how to interpret the voltages and whether the relevant circuit is an add or an inv-add, and hence without settling in her own mind whether algorithm (1) or (2) is used, knowing well that either one (as well as many others!) is a possible interpretation of the system’s functioning.

Monday, May 4, 2020

Digital and analog states, consciousness and clock skew

In a computer, we have multiple layers of abstraction. There is an underlying analog hardware level (which itself may be an approximation to a discrete quantum world, for all we know)—all our electronic hardware is, technically, analog hardware. Then there is a digital hardware level which abstracts from the analog hardware level, by counting voltages above a certain threshold as a one, below another—lower—threshold as a zero. And then there are higher layers defined by the software. But it is interesting that there is already semantics present at the digital level: three volts (say) means a one while half a volt (say) means a zero.

At the (single-threaded) software level, we think of the computer as being in a sequence of well-defined discrete states. This sequence unfolds in time. However, it is interesting to note that the time with respect to which this sequence unfolds is not actually real physical time. One reason is this. At the analog hardware level, during state transitions there will be times when the voltage levels are in an area that does not define a digital state. For instance, in 3.3V TTL logic, a voltage below 0.8V is considered a zero, a voltage above 2.0V is considered a one, but in between what we have is “undefined and results in an invalid state”. Since physical changes at the analog hardware level are continuous, whenever there is a change between a zero and a one, there will be a period of physical time at which the voltage is in the “undefined” range.

It seems then that the well-defined software state thus can only occur at a proper subset of the physical times. Between these physical times are physical times at which the digital states, and hence the software states that are abstractions from them, are undefined. This is interesting to think about in connection with the hypothesis of a conscious computer. Would a conscious computer be conscious “all the time” or only during the times when software states are well defined?

But things are more complicated than that. The technical means by which undefined states are dealt with is the system clock, which sends a periodic signal to the various parts of the processor. The system is normally so designed that when the clock signal reaches a component of the processor (say, a flip-flop), that component’s electrical states have a well-defined digital value (i.e., are not in the undefined range). There is thus an official time at which a given component’s digital values are defined. But at the analog hardware level, that official time is slightly different for different components, because of “clock skew”, the physical phenomenon that clock signals reach different components at different times. Thus, when we say that component A is in state 1 and component B is in state 0 at the same time, the “at the same time” is not technically defined by a single physical time, but rather by the (normally) different times at which the same clock signal reaches A and B.

In other words, it may not be technically correct to say that the well-defined software state occurs at a proper subset of the physical times. For the software state is defined by the digital state of multiple components, and the physical times at which these digital state “count” is going to be different for different components because of clock skew. In fact, I assume that the following can and does sometimes happen: component B is designed so that the clock signal reaches it after it has reached component A, and by the time component B is reached by the clock signal, component A has started processing new data and no longer has a well-defined digital state. Thus at least in principle (and I don’t know enough about the engineering to know if this happens in practice) it could be that there is no single physical time at which all the digital states that correspond to a software state are defined.

If this is right, then when we go back to our thought experiment of conscious computer, we should say this: The times of the flow of consciousness in that computer are not even a subset of the physical times. They are, rather, an abstraction, what we might call “software time”. If this is right, the question of whether the computer is presently conscious will be literally nonsense. The computer’s software time, which its consciousness is strung out along, has a rather complex relationship to real time.

So what?

I don’t know exactly. But I think there are a few directions one could take this line of thought:

Consciousness has to be strung out in a well-defined way along real time, and so computers cannot be conscious.

It is likely that similar phenomena occur in our brains, and so either our consciousness is not based on our brains or else it is not strung out along real time. The latter makes the A-theory of time less plausible, because the main motive for the A-theory is to do justice to our experience of temporality. But if our experience of temporality is tied to an abstracted software time rather than real time, then doing justice to our experience of temporality is unlikely to reach the truth about real time. This in turn suggests to me the conditional: If the A-theory of time is true, then some sort of dualism is true.

The problem that transitions between meaningful states (say, the ones and zeros of the digital hardware level) involve non-meaningful states between them is likely to afflict any plausible theory on which our mental functioning supervenes on a physical system. In digital computers, the way a sequence of meaningful states is reconstructed is by means of a clock signal. This leads to an empirical prediction: If the mental supervenes on the physical, then our brains have something analogous to a clock signal. Otherwise, the well-defined unity of our consciousness cannot be saved.

Sunday, April 5, 2020

Paddles for classic video games

Saturday, November 23, 2019

Intending the end without intending the known means

It is said that:

- he who intends the end intends the means.

But the person who doesn’t know how a computer keyboard works does intend to close circuits when writing an email, even though the closing of circuits is the means to writing emails.

Perhaps, though, when they learn how computer keyboards work, that might change their intention, so that now they intend to close circuits whenever they intentionally type a character? But that is psychologically implausible: the activity of the practical intellect involved in typing is normally unchanged by learning how a keyboard works. (There are, of course, special circumstances where it may change. For instance, if one knows that one is near some very delicate electrical equipment whose functioning could be affected by the closing of these circuits, then one’s deliberation might change.) The knowledge of what happens in typing remains merely non-occurrent knowledge, not affecting the activity of the practical intellect or the will.

One might think, though, that if one occurrently knows that the means to typing an email is the closing of circuits, one is intending to close circuits. But even this need not be true. For instance, a person who is writing a technical article on how keyboards work may well be occurently knowing that their movements are transformed into data in computer memory by means of closing electrical circuits, but this occurrent knowledge may very well still not affect either their practical intellect or their will. (Indeed, when I wrote the opening paragraph of this post, I no doubt occurrently knew how keyboards work, but I don’t think this affected my intentions.)

For one’s knowledge to affect one’s intentions it needs to enter into the deliberation. For that, it needs to be occurrently and practically taken by the agent as practically relevant. For most people under most circumstances, that computer keyboards work by closing circuits is not practically relevant. But if it is Sabbath and one is an Orthodox Jew who believes that closing circuits is forbidden on the Sabbath, then the knowledge is apt to be taken as practically relevant: if one still types, that is apt to become an act of rebellion or of akrasia, and if one refrains from typing, that act is apt to be done as a mitzvah. However, one could imagine the sad case of such an Orthodox Jew who types on the Sabbath anyway, and eventually becomes so calloused that the fact that circuits are being closed stops entering into deliberation, though the fact is still known by the theoretical intellect. Such a person’s intentions may eventually drift to those of the typical gentile.

So, what is one to say about the principle that he who intends the end intends the means? There is of course a trivial version:

- he who intends the end intends the intended means.

Maybe we can do a little better:

- in intending the end one intends the means insofar as they enter into deliberation.

I am not sure this is right, but it’s the best I can do right now.

Note an interesting thing. If this last version is right, then the means may enter into deliberation on the opposite side, against the action. For instance, if one thinks it’s forbidden to close electrical circuits on the Sabbath, but one chooses to do so, that the means involve the closing of electrical circuits is apt to enter into deliberation on the con side of typing, not on the pro side (unless one is positively rebellious).

Saturday, September 16, 2017

Adding a USB charging port to an elliptical machine

Tuesday, May 30, 2017

Drawers for small electronic components

Wednesday, June 29, 2016

IRToWebThingy

For quite some time, my older daughter has wanted me to make her Great Wolf Lodge Magiquest wand do something at home. So I made a simple IRToWebThingy (the link gives build instructions). It takes infrared signals in many different infrared remote controls and makes them available over WiFi. As a result, we can now watch Netflix with a laptop and a projector and the ceiling and play/pause with the Magiquest wand (and adjust volume with our DVD remote) with a pretty simple python script. My son (with some help) made a 3D etch-a-sketch script that lets him draw in Minecraft with the DVD remote. I made a fun script that lets you fly a pig in Minecraft with a Syma S107 helicopter remote (see photo). You can even control rooted Android devices with IR remotes and shell scripts.